Yves here. Banking systems are regularly saddled with too many bad loans. The common approaches have been to pretend that the loans will eventually recover, which often results in long-term stagnation or borderline depression (see Japan and Italy) or having borrowers take an undue amount of damage, which increases inequality, hurts growth, and erodes institutional and political legitimacy.

This post suggests an alternative: that of more equitable burden sharing through a partial debt jubilee.

By T. Sabri Öncü (sabri.oncu@gmail.com), an economist based in New York. This article first appeared in the Indian journal Economic & Political Weekly on 9 March 2017

I closed the November 2016 H T Parekh Column article (Öncü 2016) as follows: “A global Jubilee is in order.”

This was my proposal to tackle the difficulty of resolving the “private debt overhang” problem in the current global environment of low nominal output growth. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) issued a warning in the title of its October 2016 Fiscal Monitor: “Debt—Use It Wisely” (IMF 2016).

In this article, I propose that India lead the world.

What is Jubilee?

Jubilee comes from Judaic Law (Leviticus 25). It is a clean slate to be proclaimed every 49 years (seven Sabbath years—Sabbath means to cease, to end or to rest) annulling personal and agrarian debts, liberating bond-servants to rejoin their families, and returning lands that had been alienated under economic duress (Hudson 2013).

Jubilee is not a religious fiction or ideal as some think it is. It has been traced back to royal proclamations issued in Sumer and Babylonia in the third and second millennia BC. It used to happen quite often, and debt write-offs happen quite regularly even these days (Öncü 2016).

What are Zero Coupon Perpetual Bonds?

The oldest known perpetual bond in the world that still pays coupon (at an interest rate of 2.5%) was issued in 1624. It was originally floated to raise funds for the repair of a dike by the Hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams, a Dutch water authority responsible for maintaining levees (Andrews 2016). As the name suggests, a perpetual bond never pays principal. It pays coupons with some stated frequency on the stated principal (the face value or the price it was issued) only.

But, what if a perpetual bond does not pay any coupon either? At what price would such a bond sell other than zero? How much would it cost to issue the bond to its issuer other than almost nothing?

As crazy as the zero coupon perpetual bond idea may sound, the banknotes we carry in our wallets are essentially zero coupon perpetual bonds. They pay neither coupon nor principal. Yet, they have face values written on them such as ₹100 or ₹500. And, they buy things at their face value.

The most recent zero coupon perpetual bond proposal belongs to the former chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of the United States (US), Benjamin Bernanke, and earned him the nickname “Helicopter Ben”. In July 2016, Bernanke proposed to “Japan that helicopter money—in which the government issues non-marketable perpetual bonds with no maturity date and the Bank of Japan directly buys them—could work as the strongest tool to overcome deflation” (Fujiko and Ujikane 2016).

I will propose zero coupon perpetual bonds to India also. But, not in the way Bernanke proposed them to Japan.

Non-performing Assets in India

The non-performing assets (NPAs) of the Indian banking sector have been on the rise since September 2008, with faster deterioration after September 2009. Interestingly, while the private sector banks were suffering from most of the NPAs in September 2008, after September 2009 the public sector banks have started to take the lead and, now, the public sector banks are suffering from most of the NPAs (Unnikrishnan and Kadam 2016).

The deterioration that started in September 2008 continued until the last quarter ending 31 December 2016, and NPAs reached 9.3% of the total credit extended by the entire (public and private) banking system, while NPAs of public sector banks were 11% of the total credit they extended. What is worse is that five of the public sector banks had NPAs of above 15%. The size of the NPAs of the entire banking system at the end of this quarter was ₹6.7 trillion and 88.2% of this amount was on the books of the public sector banks (Mathew 2017).

As noted by Chandrasekhar (2017), the Indian Ministry of Finance’s Economic Survey 2016-17 recognised that under normal circumstances this would have threatened the banks concerned with insolvency, perhaps triggered a bank run, forced bank closure and even precipitated a systemic crisis. Chandrasekhar (2017) also noted that according to the Survey, since there is belief that these banks have the backing of the government, which will keep them afloat, the bad loan problem has not, as yet, become a systemic crisis. Whether the bad loan problem in India has become a systemic crisis or not can be debated. However, that India needs to decisively resolve her banks’ stressed (nonperforming, restructured or written-off) assets with a sense of urgency the newly appointed Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Deputy Governor Viral Acharya mentioned in his 22 February 2017 speech cannot be.

Proposals on the Table

A “bad bank” is a corporation established to isolate stressed assets held by a bank or financial institution, or a group of banks or financial institutions. It might be established privately by the bank or financial institution, or the group of banks or financial institutions, or by the government or some other official institution.

There have been two main proposals to tackle the stressed asset problem of the Indian banks since the beginning of this year. The first one was the “bad bank” proposal made in the Survey:

“NPAs keep growing, while credit and investment keep falling. Perhaps it is time to consider a different approach—a centralised Public Sector Asset Rehabilitation Agency [PARA] that could take charge of the largest, most difficult cases, and make politically tough decisions to reduce debt.”

The PARA to resolve the stressed assets of the public sector banks is the “bad bank” the Finance Ministry proposed. The Survey gives a detailed description of how the PARA would work and mentions that the funding for PARA would come from three sources: (i) the government issued securities; (ii) the capital market and (iii) the RBI. The first two of these sources are not unusual. However, the third source is rather unusual (although not novel as the Survey documents):

The RBI would (in effect) transfer some of the government securities it is currently holding to public sector banks and PARA. As a result, the RBI’s capital would decrease, while that of the banks and PARA would increase. There would be no implications for monetary policy, since no new money would be created.

The second proposal came from the RBI Deputy Governor Viral Acharya on 22 February 2017. Although rumour has it that he was hired for his advocacy of “bad banks”, Acharya clarified that his suggestion is not akin to creating a “bad bank”, but is more to create a resolution agency. He suggested two models. A Private Asset Management Company (PAMC) and a National Asset Management Company (NAMC).

Under the PAMC, banks would come together to approve a resolution plan based on proposals from a variety of different restructuring agencies and vetted by rating agencies. As he explained, there

are ways to arrange and concentrate the management of these assets into a single or few private asset management companies (PAMCs), at the outset or right after restructuring plans are approved. These companies would resemble a large private-equity fund run by a team of professional asset managers. Besides bringing in their own capital, they could raise financing from investors against equity stakes in individual assets or in the fund as a whole, i.e., in the portfolio of assets (Mathew and Dugal 2017).

As Acharya argued, the PAMC would be more suitable for sectors such as steel and textiles where some sectoral recovery is in sight whereas the NAMC—in which the government would play a larger role—would be more appropriate for infrastructure investments such as power where the assets may appear to be unviable in the short to medium term. However, even the NAMC would bring in asset managers such as Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) and private equity to manage and turn around the assets, individually or as a portfolio, although the government may retain a minority stake in the assets.

To sum up, while the Finance Ministry proposed a mainly public solution, Acharya proposed mainly private or market solutions to the problems.

My Criticism of the Proposals

Although given the urgency of the situation both proposals have many merits, many have attacked both of the proposals for a multitude of theoretical and ideological reasons. This is normal of course because economics is not even the “dismal” science as some call it. What is wrongly called economics these days used to be correctly called political economy as the following title from the 27 February 2017, Times of India demonstrates (Sidhartha 2017): “Few Supporters in Govt for ‘Bad Bank’ Proposal.”

Here is a quotation from this article.

Sources in the finance ministry, however, said that the issue is best left to banks as the government did not have the required resources to meet the capitalisation needs. In addition, it does not want to be seen bailing out companies and banks when the same resources can be deployed elsewhere.

The above is what I mean when I say there is no economics but political economy. Under these conditions, it would be unfair to criticise either of the proposals, but I have to criticise both on one account.

It is that both of the proposals operate under the implicit assumption that “banks are financial intermediaries”.

The problem is that banks are not financial intermediaries. They are money creators. Banks create money either by extending credit or by buying government securities while in the process creating the corresponding deposits. In other words, banks do not collect or mobilise deposits to lend them out. Although banks can collect deposits from each other, when we look at the entire banking system as a single bank, there is no other place from which this bank can collect deposits except the holders of currency in circulation. That is, the banking system does not collect or mobilise deposits first and then extend credit or buy government securities. It is the other way around.

Lost Century in Economics

In an article titled “A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence”, Werner (2016) argue the following.

During the past century, three different theories of banking were dominant at different times: (1) The currently prevalent financial intermediation theory of banking says that banks collect deposits and then lend these out, just like other non-bank financial intermediaries. (2) The older fractional reserve theory of banking says that each individual bank is a financial intermediary without the power to create money, but the banking system collectively is able to create money through the process of ‘multiple deposit expansion’ (the ‘money multiplier’). (3) The credit creation theory of banking, predominant a century ago, does not consider banks as financial intermediaries that gather deposits to lend out, but instead argues that each individual bank creates credit and money newly when granting a bank loan. The theories differ in their accounting treatment of bank lending as well as in their policy implications. Since according to the dominant financial intermediation theory banks are virtually identical with other non-bank financial intermediaries, they are not usually included in the economic models used in economics or by central bankers. Moreover, the theory of banks as intermediaries provides the rationale for capital adequacy-based bank regulation. Should this theory not be correct, currently prevailing economics modelling and policy-making would be without empirical foundation (emphasis added).

In a working paper by the Bank of England titled “Banks are not intermediaries of loanable funds—and why this matters,” Jakab and Kumhof (2015) describe the money creation process as follows.

In the intermediation of loanable funds model of banking, banks accept deposits of pre-existing real resources from savers and then lend them to borrowers. In the real world, banks provide financing through money creation. That is, they create deposits of new money through lending, and in doing so are mainly constrained by profitability and solvency considerations.

In this paper, Jakab and Kumhof quoted Alan Holmes (1969), a former vice president of the New York Federal Reserve, who wrote the following: “In the real world, banks extend credit, creating deposits in the process, and look for the reserves later.”

How is Money Created in India?

In 1969, Holmes was talking about the US. The situation is somewhat more complicated in India because there have been two liquidity requirements imposed on the banks by the RBI after the independence. These two requirements are called the cash reserve ratio (CRR) and the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR).

Prior to further progress, let me clarify what the RBI means by “cash”.

In the language of the RBI, “cash” does not mean just the rupee banknotes, and the rupee and smaller coins. Beyond these three are the “bank deposits” with the RBI which are just some numbers on some computers these days. So, rather than “cash” and consistent with the rest of the world, I will use the word “reserves” for these “bank deposits” with the RBI and save the word “cash” to mean what we ordinary people think “cash” is in our daily lives. The economists call the sum of cash and reserves, base money, whereas the sum of cash and deposits is broad money. It should be mentioned that while cash and deposits can buy things in the real world, reserves cannot. Reserves are common currency only among the banks and the RBI, and cannot go out of the banking system.

To sum up, the CRR is what the most of the rest of the world calls the “required reserve ratio”. As Holmes (1969) described for the US, the banks first create deposits by extending credit or buying government securities and then look for reserves to meet the CRR requirement also in India. The most recent banking data available at the RBI website—as of 17 February 2017 at the time of writing—shows that the reserve to deposit ratio was about 4%, which is consistent with the current CRR requirement.

And, had the CRR been the only liquidity requirement, the money creation process in India would have been no different than the money creation process in the US, for example. What sets India apart from most other countries is the SLR requirement. Because, the SLR requirement can be met not only by holding “reserves”, but also by holding gold and “government approved securities”.

When we look at the SLR historically, we see that the commercial banks in India have met their SLR requirement by holding “government approved securities” mostly. In addition, if we look at the above-mentioned RBI data we see also that way above 99% of the “government approved securities” were “government securities”. This comes as no surprise because these securities are very safe and pay high interest rates.

Further, as of the same date, the credit to deposit ratio was roughly about 70% while the government approved securities to deposit ratio was roughly about 30% and these two ratios nearly added up to 100% despite the expected measurement errors. Given that the current SLR requirement is 20.5%, this indicates also that the banks are holding way more government securities than they are required. This is understandable, because the banks need non-SRL government securities to repo (see, for example, Acharya and Öncü 2010 for a description) with the RBI to obtain reserves to meet their CRR requirement.

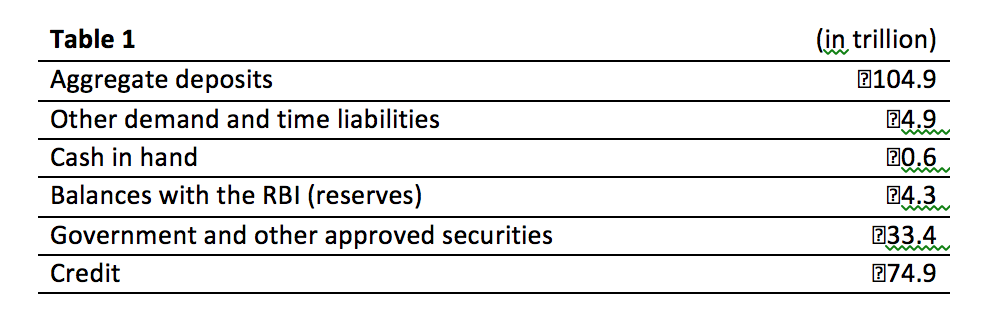

To sum up, while the CRR is a tool of the RBI to manage the liquidity in the banking system, the SRL is a tool to manage the liquidity in the economy, although nowadays the RBI uses the CRR to manage the liquidity in the economy also. To clarify these further, let me summarise the 17 February 2017 data from the above mentioned RBI website.

And, let me add to this that the total of all outstanding government securities is ₹47.2 trillion.

These data show that the commercial banks in India hold about 70% of all outstanding government securities and hence the SLR is not only a monetary policy tool, but also ensures the banks in India lend to the government. Furthermore, the availability of government securities puts an upper bound on the deposits the Indian banks can create.

If the banks buy all of the governments securities and use them to meet the 20.5% SLR requirement only, then the banks in India can increase the aggregate deposits to ₹230.4 trillion by extending additional credit. In this case, the credit extended to the rest of the economy other than the government would be ₹183.2 trillion. This is the maximum amount of credit that can be extended to the rest of the economy, if the government does not issue new securities and the SLR remains 20.5%. Further, in this scenario, the RBI has to increase the reserves to ₹9.2 trillion so that the banks can meet their 4% CRR requirement.

Of course, the above is just a hypothetical scenario I constructed to give the readers some idea about how these two ratios, reserves and government securities affect the availability of money and credit to the economy.

My Bad Bank Proposal

In light of the discussion so far, I now make my “bad bank” proposal to India and, for want of a better name, call it the Bad Bank.

- The Bad Bank would be promoted by the Government of India and capitalised with zero coupon perpetual bonds the government would issue;

- The Bad Bank would swap the zero coupon perpetual bonds with reserves the RBI would create. These reserves would be excess, because they would not back any of the deposits of the banking system;

- The Bad Bank would swap the excess reserves with the banks (public and private) for the bad loans.

Two things will happen to the banks (not just public, but also private):

- They are relieved of the bad loans;

- Since the excess reserves have zero risk weights, their capital ratios go up so that there is no need to recapitalise any of the banks.

Furthermore, although the base money was increased by the amount of the issued zero coupon perpetual bonds, since the existing deposits remained intact, the broad money neither increased (no immediate inflation) nor decreased (no immediate deflation). In addition, this operation would cost nothing either to the Government of India or to the Indian taxpayers, because the Government of India will pay neither coupon nor principal on the issued zero coupon perpetual bonds.

At this point, a decision has to be made regarding what to do the with the bad loans. One possible decision is to erase all of the bad loans against the Bad Bank’s equity and dissolve the Bad Bank. This is what I call a partial Jubilee. It is partial because in a full Jubilee, all of the debts in the country would be annulled and the country would start from a clean slate.

Of course, this is not the only possible decision. As in the case of the NAMC proposed by Acharya, the Bad Bank might bring in asset managers such as ARCs and private equity to manage and turn around the assets, individually or as a portfolio, and the like. Other possibilities can also be considered.

Let me conclude by noting that although what I proposed above solves the immediate stressed asset problem of the Indian banking system cheaply, it does not solve any other problems, be those economic, financial, political, social and the like. It only gives the country some breathing time so that she can attack and tackle all of her other problems.

Last Words

One last issue I would like to discuss is the excess reserves the RBI created. As readers familiar with the quantitative easing (QE) programmes implemented in the US would recall, many have expressed concern that the large quantity of excess reserves created through the QE programmes will lead to an increase in the inflation rate unless the Federal Reserve acts to remove them quickly once the economy begins to recover.

In an article titled “Why Are Banks Holding So Many Excess Reserves?” Keister and McAndrews (2009) addressed this issue and argued that if interest is paid on the reserves, this allows a central bank to maintain its influence over market interest rates independent of the quantity of reserves created by its liquidity facilities. This can also be considered in India. Furthermore, despite all these concerns in the beginning, no significant inflation took place in the US and, indeed, in 2015, the US was flirting with deflation.

And, of course, there is the luxury of the SLR that the RBI can use to manage the liquidity in the economy.

References

Acharya, Viral, V. and T. Sabri Öncü (2010): “The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and a Little Known Corner of Wall Street: The Repo Market”, NYU Stern Regulating Wall Street Blog, 16 June,

http://w4.stern.nyu.edu/blogs/regulatingwallstreet/shadow-banking/repo-market/2010/07/

Andrews, Evan (2016): “6 Longstanding Debts from History,” History Lists, 2 December, http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/6-longstanding-debts-from-history

Chandrasekhar, C P (2017): “Wicked Loans and Bad Banks,” Frontline, 1 March.

Fujiko, Toru and Keiko Ujikane (2016): “Bernanke Floated Japan Perpetual Debt Idea to Abe Aide Honda,” Bloomberg, 14 July

Holmes, Alan (1969): “Operational Constraints on the Stabilization of Money Supply Growth”, in: Controlling Monetary Aggregates, Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 65-77.

Hudson, Michael (2013): “J Is for Jubilee, K for Kleptocrats,” The Insiders Economics Dictionary, 26 November.

IMF (2016): Fiscal Monitor: Debt—Use It Wisely, International Monetary Fund, Washington, October.

Jakab, Z and M Kumhof (2015): “Banks Are Not Intermediaries of Loanable Funds—and Why This Matters,” Bank of England Working Paper No 529, May.

Keister, Todd and James McAndrews (2009): “Why Are Banks Holding So Many Excess Reserves?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 380, July.

Mathew, George (2017): “Bad loan crisis continues: 56.4 per cent rise in NPAs of banks,” Indian Express, 20 February

Mathew, Alex and Ira Dugal (2017): “RBI’s Viral Acharya Proposes ‘Tough Love’ To Resolve Bad Loan Crisis,” Bloomberg-Quint, 22 February

Öncü, T. Sabri (2016): “It is the private debt, stupid!” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol.51 (46), pp 10-11

Sidhatha (2017): “Few Supporters in Govt for ‘Bad Bank’ Proposal,” Times of India, 27 February.

Unnikrishnan, Dinesh and Kishor Kadam (2016): “Explained in 5 charts: How Indian banks’ big NPA problem evolved over years”, Firstpost, February 10.

Werner, Richard A. (2016): ““A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence,” International Review of Financial Analysis, Vol. 46, July, 361-79.

In other words the Government will monetize the bad debts.

He already states that Currency in circulation is a Zero coupon note. If the new bonds and currency in circulation are fungible, this is just a case of the government buying all the non-performing loans at face value.

That’s the point. Then canceling them, or at least partially canceling them. Jubilee style.

michael-hudson.com/2017/01/the-land-belongs-to-god/

I am baffled.

As you state it is equivalent to the government buying all bad debts and making them disappear from the economy.

What happens to those zero-coupon perpetual bonds once they have been swapped for reserves at the RBI? From what I understand, they are reduced to an entry in the balance sheet of the RBI that will never go away, never change, never produce any financial movement. Cash, considered as zero-coupon perpetual bonds, at least circulate in the economy and thus have a permanent utility. Those other bonds would serve exactly once and then be eternally frozen.

This mechanism to get rid of debts without cancelling them so that the creditors do not lose anything seem like too good a sleight of hand to be true.

I wish somebody well-versed in finance could chime in on the consequences. For one, if the State is ready to buy all bad debts for fictitious money, why should banks care about whether debtors are solvable or not and just pile up credit that will be absorbed by the RBI when going bad? A jubilee would at least have creditors learn a lesson by effectively losing assets (i.e. the NPA).

The bonds disappear into thin air. Just like the deficits that are “funded” with RBA reserves. They don’t exist, which is the essence of a fiat currency.

What are the financial implications? Well, the FIRE sector becomes disengaged, because the reality strikes home that they add no economic value within their transactions – aka, it is a transaction of government, so the FIRE parasites have no coupons to clip. They will be pissed! What happens in the real economy is determined by the availability of productive resources and whether the output of those resources are purchased (cleared) at current prices. If so it is a null effect if not, then deflation or inflation will eventuate unless the Central Bank adjusts interest rates to counter the deflation/inflation effect.

Monetary capability of a currency issuing sovereign with a floating exchange rate is absolute and the financialised economy (FIRE sector) has little part to play. The reason it is so difficult to get this message across could be termed Wall Street Obfuscation aka vested financial interests capture of Government thinking to produce a canker of groupthink. Like all financialised economies there is a saturation point where private debt is exhausted against asset values and a slight misstep or shock within an economy tips the balance like the sub prime fiasco. Because the Government is in lockstep with the groupthink we get the outcomes created by Obama who was poorly advised by bureaucrats party to the groupthink cycle. It is a problem of economic literacy and imo the reason why basic economics is not taught in primary and secondary education. If it was then citizens could hold the politicians to account, but vested interests don’t want that at any cost.

The program seams sound to me, but I’m hardly an expert. Curious though that his twitter is a lot of RT’s from Zero Hedge, congratulating his good friend Mnuchin for getting confirmed at treasury and then a link to a good Ann Pettifor piece.

http://www.primeeconomics.org/articles/g0nbzfni9ae3boi5urr2jvyslp6can

Bad translation from Turkish. I was not congratulating Mnuchin. Nor is he my friend. I don’t know him. Calling someone a “friend” is a way to address a person in Turkish. The person doesn’t have to be your friend in reality. Like, I can call you my friend, but we don’t know each other as you know :)

As an Indian reader, I am very glad that NC has covered this issue of NPAs and the fundamental misunderstanding of money creation/banking by the relevant authorities, pvt and public. You will be amazed how our best finance and management/business schools teach their students this most basic of concepts incorrectly, considering the hyper competitiveness required to get in them and the prestige/brand value they carry in they eyes of the everyday Indian.

Also, glad the author has explored to workings of the money creation system in the context of Indian rules and regulations.Please keep this up! :)

Interesting, thought-provoking post that creatively addresses the NPA burden on India’s banking sector (a huge, looming elephant in the room). I’ll be forwarding this widely.

“Furthermore, despite all these concerns in the beginning, no significant inflation took place in the US and, indeed, in 2015, the US was flirting with deflation.”

Spoken like a true banker :)

Actually, no, bankers see inflation everywhere just the way another Joe, Joe McCarthy, saw Commies under every bed.

And talk of deflation does not make bankers happy since super low interest rates, which is all central bankers seem to think they can do to address the problem, kill bank profits. One of the big reasons the Fed is so over-eager to raise interest rates is that bankers have been pressuring them to do so.

So, kudos and thanks to the author for presenting an idea that would solve the problem for the banks. It is an innovative idea and shows a firm grasp of the way money and economies actually work. However, I would encourage the author to extend his commentary to elaborate on two other things. First, what debt relief would be provided to the end borrower—be it a business or a household? The economy will not get full benefit unless those end borrowers get relief. I would suggest some kind of special requirement that the bad banks act to give generous relief to borrowers in an accelerated time frame. For example, if a household were given relief on an underwater mortgage, the lender could be given a percentage of the future sale of that house. The second issue is the consequence to the banks. I would suggest that any bank that has let problem loans rise to the high levels outlined in this article be required to replace the board and top management in exchange for the relief described here. In any event, kudos to the author.

Thanks. I think what I proposed would be helpful for the European Banking Crisis as well. Furthermore, it might offer an easy solution to unwinding of the QEs, if you know what I mean.

Ha! I initially misinterpreted the article’s title. I briefly thought the article was about a bad proposal for a bank issue. But the article is about a proposal for dealing with the problem of bad loans by creating a bank for those loans: a bad bank.

I don’t know whether the author’s proposal is a good one or not, because I have insufficient expertise, but it is interesting. And my confusion about the title should be a lesson to anyone who thinks that he or she can understand an article without actually reading it. As Yves sometimes says to commenters: “Did you read the article?”

A “bad bank” is now commonly used; I saw them first hand in the 1980s as a way to clean up sick financial institutions. I have to believe they weren’t a new idea then but calling them “bad banks’ may have been new branding at that time.

Basically the idea is that you take the bad loans out of the institution, put them in a separate entity, and figure out what to do with them. We did this with the Resolution Trust Corporation, when a whole bunch of S&Ls died all at once. Sweden also did this in its early 1990s banking crisis, and they got better results than many others using this approach did because 1. They allowed the people running the operation more time to work out loans and 2. They allowed them money to invest selectively. For instance, consider a loan against a 3/4 completed hotel project that failed not because the project was bad per se but the borrower had gotten the bank to let him proceed with just about no equity and then he got caught in the downdraft of the bad recession. If you went the conventional route and liquidated it, you’d have more than 100% losses because you’d have to pay to demolish the hotel to get someone to bid on the land. So if you found a hotel manager and finished the development, you’d almost certainly come out ahead.

This is the moral hazard question that will always bedevil money creation by ‘private in the good times, public in the bad’ institutions under the auspices of the state.

Being fortunate enough to be given the power to create debt/money at a keystroke according to near permanent demand is one thing, but to do so at little or no personal risk or sanction to oneself is truly a blessing from the financial gods aka nice ‘work’ if you can get it.

We know who mostly reaps the rewards, but who exactly bears the consequences of these bad loans, these misjudgements or these all too often reckless self-serving decisions, and what’s to stop taxpayers and bona fide, diligent borrowers being rinsed in future by feckless lenders and the process repeated indefinitely I wonder?

I’m not sure I follow. As it stands, banks create credit money basically at will, no matter the social or inflationary cost, because “private sector knows what it’s doing”. Given that they can’t handle this responsibility, why should the conclusion be to not intervene? (And no, taxpayers and chimeric ‘bona fide, diligent borrowers’ do not need to lose out when this is fixed via jubilee.) Of course, they’ll also need to cap loan creation (per sector or however) to prevent recurrence, but the fact that that’s (relatively) novel shouldn’t keep them from trying.

‘Fiat’ currency is just that, and it’s called that for a reason.

The people that mostly give it that crucial credibility are those that underwrite it and I don’t mean ‘those’ that have the power to create it at will, possess most of it, are dependent and hooked on state largesse, or make it their daily business to make more of it in their sleep at the expense of others.

The ‘those’ I am talking about are effectively those that labour productively, drive demand and dutifully pay their fair taxes (to help reduce the money supply) and borrow at a fair rate to drive demand and expand the money supply, but crucially do their level best to pay it back (and simultaneously reduce it) and maintain a vital equilibrium.

There are a myriad of reasons why personal loan rates in Venezuela and Zimbabwe aren’t exactly generous and why international creditors either won’t touch them with a barge pole or demand usurious rates of return and I’m pretty sure it’s not down to a national shortage of easy money seeking, corrupt, self-serving, opportunistic, short-termist, greedy sh*ts, believe me.

Debt jubilees are a great idea, in certain circumstances, when they may act as clean slate, but are truly toxic if they serve to reinforce, legitimise or instill destructive behaviour in an increasingly dysfunctional kleptocratic system.

Would recommend that you read these two posts as a starting point, as, contrary your expressed underlying desire to aid those who need, you’re currently repeating ideas that only aid reactionaries:

Thanks for the patronising, evasive response.

I listened to and enjoyed his series of programmes about the history of debt on BBC Radio 4.

If I want any recommended reading I’ll ask, as I’m sure you will of me.

I’m confused. Will someone please think past the balance sheets for me and discuss how issuing government backed zero coupon perpetual bonds to liquify private banking is going to play out in a world where banking for profit has destabilized actual collateral – as in there isn’t any left. So rehypothecation. It’s a little nutty if the goal is to rebalance banks’ balance sheets. The only reason for a jubilee is to relieve the burden of debt on people at a point when it is obvious there is no growth/value left in the economy to exploit in order to pay back the debt. Bailing out the banks with their own jubilee (in fact it is implied they can issue their own private bonds and forgive them all by themselves!) achieves even more rehypothecation and poverty to my thinking. Maybe it worked in Holland in the 1600s for one over-extended consortium but today the whole world is overextended. This has nothing to do with MMT (which is prolly the only solution) but is instead the exact opposite. No?

I stopped reading when the author referred to a former Chairman of the Federal Reserve as “Benjamin Bernanke”.

His name is Ben Bernanke.

Ben.

Sorry to be such a stickler for detail, but if you can’t even get the names of the major players right….

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ben-Bernanke Ben Bernanke, in full Benjamin Shalom Bernanke (born December 13, 1953, Augusta, Georgia, U.S.), American economist, who was chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (“the Fed”; 2006–14).

On a purely speculative note, I bet he hates being called Benjamin.

Agree.

Probably because he was born Ben Shalom Bernanke.

I’ve sourced my source, which having been said, is a pretty damn solid source, please source your source disproving my source.

Guess why I called him Benjamin? :)

Only problem is these ideas assume loans turned bad due to business risk not outright fraud. These ideas are as much crime jubilee as debt jubilee

Link? Borrowers are regularly overly-optimistic. That’s why bankers are supposed to be skeptical, but then they get competitive or told to meet production targets and make crappy loans.

Never attribute to malice that which can be explained by incompetence. Not sayin’ there wasn’t fraud, but the onus is on you to prove that the overwhelming majority of loans were “criminal”.

And you didn’t even bother reading the piece, which is a violation of our written site policies. Even the headline said “partial” jubilee. The equity of the lenders gets wiped out. They take a hit.

I have no doubts that there had been fraud. This is why I said writing off all the bad loans is one of the possibilities. It is the simplest solution. Further, what I suggested does not solve anything other than the immediate stressed asset problem of the Indian banks. All other problems remain. I would prefer a full Jubilee that would wipe out much of the deposits as wealth inequality is as bad a problem as debt overhang problem, but even a partial Jubilee appears too much to expect at the current time. Minds are not set to accept a proposal such as mine.

Sabri Öncü – How come you decided to pay attention to Indian banks ? In my experience, the people in your professions dont really pay much attention to India as compared to other countries. And how bad do you think it is amongst the Indian finance industry, their understanding of the bank money creation/lending process?

I had worked at the CAFRAL, RBI from Jan 2012 to Jan 2014. I was the first Head of Research of CAFRAL. Had lived 2 years in Mumbai :)

Ah! Can you give some insight into how many people in RBI know how banks actually create money/make loans? And how did you come to this conclusion as well? Via experience or reading?

Well. I don’t know anyone at the RBI who knows how the banks create money/make loans. Viral Acharya is a friend. I wrote many papers with him, including a resolution proposal for the systemically important assets and liabilities. Viral understands this stuff well, but he is with the financial intermediation theory of banking, just like Raghu Rajan was. As for myself, I discovered what was going on by my own, and later discovered that I was not the only one. I am good friends with Michael Hudson. Not that I learned this stuff from him, but when we discovered that we see more or less the same things, we became good friends.

If Viral understands it well why is he with financial intermediation? Hasn’t the Bank Of England bulletin or Richard Werner’s experiment been enough to convince him? And likewise for Raghuram Rajan?

You better ask these questions to them.

Also how did you discovered what was going on? Through your own work or someone else’s like professor werner that you cited above?