Yves here. While most readers are on board with the idea that austerity is economically counterproductive, as well as politically destabilizing, it’s nevertheless important to see more and more economists, approaching the question from different angles, come to the same conclusion.

By Christopher House, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Michigan, Christian Proebsting, Scientific collaborator, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, and Linda Tesar, Professor of Economics at the University of Michigan. Originally published at VoxEU

Austerity policies implemented during the Great Recession have been blamed for the slow recovery in several European countries. Using data from 29 advanced economies, this column shows that austerity policies negatively affect economic performance by reducing GDP, inflation, consumption, and investment. It also warns that efforts to reduce debt through austerity in the depths of the economic recession were counterproductive.

Since the Great Recession of 2008–2009, recovery rates have varied widely across Europe. At one end of the spectrum is Greece, for which the ‘recovery’ never began. Greece’s per capita income at the end of 2014 was more than 25% below its 2009 level. Although Greece’s GDP performance is exceptionally negative, a contraction in GDP over the post-crisis period is not unique – about a third of European countries experienced net reductions in GDP between 2009 and 2014. At the other end of the spectrum is Lithuania. Like Greece, Lithuania experienced a strong contraction during the recession. Unlike Greece, however, Lithuania returned to a rapid rate of growth quickly thereafter.

The financial press and many economists have pointed to austerity policies that cut government expenditures and increased tax rates as an explanation for the slow recovery in several European countries (e.g. Blanchard and Leigh 2013, Krugman 2015). Our analysis finds that variation in austerity policies can in fact account for the differences in economic performance, and that these policies are sufficiently contractionary to contribute to increases in debt-to-GDP ratios in high-debt economies (House et al. 2017).

Measuring austerity

As a measure of austerity, we use the difference between predicted government purchases and actual government purchases (Blanchard and Leigh 2013). Our forecasts of government purchases include information about the current state of the economy. Thus, the resulting forecast errors can be interpreted as departures from ‘normal’ fiscal policy reactions to economic fluctuations. If spending typically increases during a recession but does not do so in the aftermath of the crisis, our procedure categorises that spending path as ‘austere’.

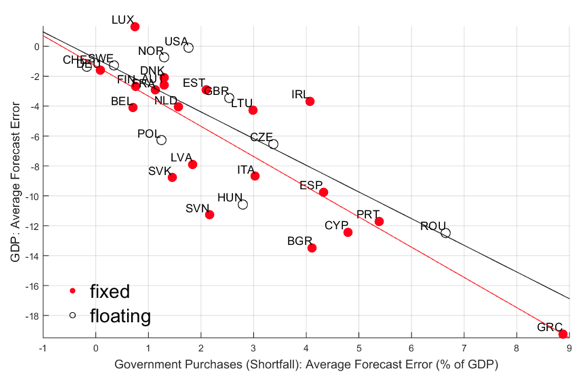

We compare our austerity measures to similarly constructed forecast errors for GDP, inflation, and other measures of economic performance. The scatterplot in Figure 1 shows the relationship between average forecast errors for GDP and government purchases in the post-crisis period (2010–14). Solid dots represent countries in the Eurozone or countries with exchange rates pegged to the euro. Open dots represent countries with floating exchange rates. The dot in the bottom right corner is Greece (GRC). Government purchases in Greece fell by almost 9% relative to pre-crisis GDP. At the same time, GDP in Greece fell by nearly 20%. In contrast, government purchases and GDP were close to their predicted values in Switzerland, Germany, and Sweden. On average, countries with more austere policies experienced greater shortfalls in GDP. The cross-sectional multiplier (the slope of the fitted line in the figure) is –2, meaning that for every €1 reduction in government purchases, GDP falls by €2. This estimate statistically controls for observed variations in taxes, productivity, debt ratios, and interest rate spreads.

Figure 1. Forecast errors in government purchases and GDP

Source: House et al (2017).

Austerity in government purchases is also negatively associated with inflation, consumption, and investment. Countries with spending shortfalls experience increases in net exports (especially for Eurozone countries) and depreciations of trade-weighted nominal exchange rates (especially for floating exchange rate countries). We find only limited evidence that tax policy had strong effects on economic performance.

How austerity affects output and debt

Many observers have criticised macroeconomic models on the grounds that they are unable to explain the main driving forces behind the global recession and its aftermath. To address this criticism, we developed a multi-country New Keynesian dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model, calibrated to data on country size, trade linkages, and exchange rate regimes. In addition to the austerity shocks, we fed in shocks to the cost of firm credit as well as monetary policy shocks. This model allows us to isolate which features of the economy and which kinds of shocks are important for explaining the data. Overall, the model generates predictions that are very close to those found in the data. The cross-sectional multiplier of government purchases in the model is roughly –2, matching our reduced-form estimates. The model generates a positive relationship between austerity and net exports and a strong negative relationship between austerity and inflation.

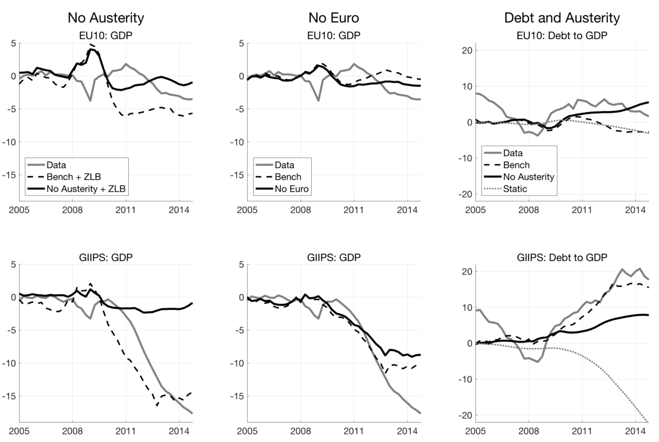

To the extent that the model replicates the reaction of European countries to actual policy changes, we can use it to consider what might have occurred had policies been different. Figure 2 shows three counterfactual scenarios: the elimination of austerity, floating exchange rates and the dynamics of debt to GDP with and without austerity. The upper panels of Figure 2 show simulated GDP trajectories for the EU10 (Belgium, Germany, Estonia, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Slovenia, the Slovak Republic, and Finland), and the lower panels show trajectories for GIIPS (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain). In the first experiment, we imposed the condition that the countries are at the zero lower bound (ZLB) in nominal interest rates. In a finding reminiscent of Nakamura and Steinsson (2014), the ZLB does not play a significant role in explaining the cross-sectional multiplier, although it is important for determining the relationship between government purchases and GDP over time (in effect, the ZLB would push down all the dots in Figure 1, leaving the slope unchanged).

Figure 2. Counterfactual policy simulation

Source: House et al (2017).

According to the model, had countries not experienced austerity shocks, aggregate output in the EU10 would have been roughly equal to its pre-crisis level, rather than showing a 3% loss. For the GIIPS economies, instead of experiencing an output reduction of nearly 18% below trend, the output losses would have been limited to 1% (the leftmost panels in Figure 2).

Allowing European nations to pursue independent monetary policy in the face of austerity shocks helps limit the drop in GDP (the middle panels of Figure 2). Relative to the benchmark model, allowing countries to have independent monetary policy would raise output for the GIIPS economies but would reduce output for the EU10. This is because the nominal exchange rate depreciates in the GIIPS region, stimulating exports and output. In contrast, under the euro, the EU10 already enjoys the export advantage of a relatively weak currency, so there is no additional benefit of a floating exchange rate.

Finally, the model allows us to consider the dynamics of the debt-to-GDP ratio under various conditions. The main rationale for austerity policies was to slow the escalation of debt-to-GDP ratios that occurred across the Eurozone (reaching close to 80% in the EU10 and 95% in the GIIPS countries in 2010). The rightmost panels in Figure 2 compare the trajectories of debt-to-GDP ratios for the EU10 and GIIPS under different assumptions. The light dotted line is a static estimate, which assumes that GDP and tax revenue are unaffected by changes in government purchases. According to this measure, austerity undertaken by the GIIPS countries should have resulted in a decline in the debt-to-GDP ratios by more than 20 percentage points from 2008 to 2014. In reality, debt-to-GDP ratios rose by 20 percentage points.

The static view misses three endogenous responses captured by our model:

- First, reductions in government purchases cause reductions in GDP;

- Second, reductions in GDP lead to reductions in tax revenue (both of these effects lead to an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio); and

- Third, some of the fiscal austerity spills over into other countries.

Taking these channels into account (the ‘benchmark’ series), our model actually predicts an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio in the GIIPS region, of a magnitude similar to that observed in the data. If no austerity measures had been implemented, the model predicts a more modest increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio for the GIIPS countries. Although we do not take the results of the model literally as a prescription for the European debt crisis, the model suggests that efforts to reduce debt through austerity in the depths of the economic recession were counterproductive.

See original post for references

Basically austerity is class warfare from the banks and rich against the poor and middle classes.

Those who got hurt by the economy are going to get hurt even more, while the rich get richer. That’s what this is all about. I think the austerity people know what’s behind the rise of the far right. Their failings and lies.

Keynesianism … during prosperity, spend only as much as necessary, but not less … during recession, spend more than necessary to keep demand up

Cronyism … during prosperity, help the rich get richer, but restrain the gains of the poor … during recession, help the rich get richer, but impose austerity on the poor

The first isn’t politically realistic … the second is.

Apt term I heard used recently for it, economic eugenics.

In short, austerity is violence.

I already call poverty “financial violence” because that’s precisely what it is.

economic eugenics

Or survival of the fittest, social darwinism, etc. I was thinking of this when I was watching a video of Thomas Frank (Listen Liberal) What to Make of the Age of Trump by Thomas Frank. He calls out how the dem party has forsaken its class roots and hitched its wagon to meritocracy, the idea that everybody gets what they deserve. Obama knew how this plays out, “This is not a bloodless process.”

Interestingly whereas “survival of the fittest” is meant to signify cornering of the market in innovation much innovation would appear to take place in government; for example, bailing out feckless bankers and distributing income top-up money in the shape of welfare payments for businesses that can’t distribute profits sensibly to keep economies steady!

Austerity a failure? Not for those who design and have the power to implement policy. Austerity does exactly what it is supposed to do. Sorry, but I don’t need to have this validated by economic analysis.

Agreed. Attributing good intentions to the neoliberal order is a conservative position which implies that we merely need new managers.

It’s not better bosses that is needed, but rather a radical transfer/takeover of power.

You might not need to have this validated by economic analysis, but look at the fruits of “because we said so”. Analysis and publication of studies like this is how paradigms change.

Is the problem that government isn’t buying enough, or it is not letting their FIRE economy buddies fail, or its not prosecuting it’s FIRE buddies for illegal acts? Why don’t we throw in the last two and see what happens. Like Iceland.

I think I (mostly) agree. While I don’t consider it to be intentional class warfare, austerity absolutely hits the less affluent to a far greater degree, whereas inflating the money supply (i.e. the opposite of austerity) tends to be a negative for the more affluent who have a more substantial savings and less debt-v-income. The world is so unbalanced now in terms of the have’s and have-not’s that this effect alone can now ruin a country. In the U.S., for example, even though we spent, inflation still stayed low and there was no great equalizing force, leaving our Economy in a weird middle-place.

I would look at it from a slightly different viewpoint though. It isn’t the country-specific austerity itself that is the problem, but instead the fact that the (e.g. Greece) economy is tied to the Euro and the EU has a strong-Euro policy. A strong Euro effectively removes a pressure relief valve… it forces what is effectively deflation on the weaker countries (slight inflation EU-wide == effective deflation in Greece, in this case). Deflation hits the less affluent with their higher debt levels very hard. In my opinion, the strong-Euro policy is at the root of the problem for the EU.

So perhaps now there will be some relief with the Euro heading to 1:1 with the dollar. But it probably isn’t enough. The weakening Euro has definitely given the EU more time to try to solve the problem. If it had stayed as strong as it was things would have already come to a head.

In the case of Greece, and in fact all the Euro countries, there is also the substantial problem in that high worker mobility creates a brain-drain in the more poorly-managed countries. We saw the same thing in Bosnia during and after the war (even without EU mobility), Basically, all the smart people left and left the stupid people in charge. I would put forth that this is probably a large driver on par with the austerity vs spending argument in that the brain drain makes it very difficult for a country to recover even after conditions change for the better.

-Matt

National budget and home budget aren’t the same. Like Greece, when I was in hard times, I couldn’t print my own money. I had to reduce expenditures radically, to not only not increase debt, but to eliminate debt accumulated during prosperity. For the EU as a whole, or GB or the US … we don’t have that money printing restriction. Keynesian stimulus is possible. Greece could have avoided unnecessary debt, and the resulting constraints during meltdown, by simply not joining the EU. But the EU never releases its hostages. It remains to be seen if the EU will release GB, without war over Gibraltar.

Sorry Matt, the Oligarchs in Europe and the US are intentionally promoting class warfare. The imbalance between haves and have-nots is deliberate and planned, We have a one dollar one vote dollar democracy. That is a feature, not a bug. They worked 50 years to undo the modest buffers of the New Deal and have been very successful. Even Warren Buffett says there was a class war and the rich won.

The underclass are coming to slowly realize that the rich are not their friends.

Austerity is a BS economic doctrine to crush the underclass. Taxes by sovereign government have only three purposes: 1.establish which money will be used by the government 2. Tamp down inflation by removing money from the system

3. Redistribute wealth to keep crazy rich individuals from getting too powerful and balancing wealth among regions of the currency zone.

Balancing the checkbook or paying off a credit card it a false analogy.

The Euro will fail because it does not do #3. It removes monetary sovereignty from nations like Greece without the wealthier entities (Germany) within the Eurozone subsidizing the poorer entities. In the US, the rich states have always subsidized the poor states. Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana have always gotten more from the Federal trough than California, NY or Mass.

Check out MMT: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_Monetary_Theory, Warren Mosler’s : http://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf and Michael Hudson’s book on Junk Economics: https://www.amazon.com/dp/3981484258

I agree that this has been intentionally promoted. In the U.S., the Powell Memorandum of 1971 is often considered to be the starting point of the current class war, but there were skirmishes even prior to that. Richard Mellon Scaife was an early ultra rich class warrior of the post-WWII period, and in the 1970s he was joined by other extremely rich people such as the rabidly anti-environmental Joseph Coors and John M. Olin. The class war really took off when Charles Koch and his sidekick David Koch started pouring massive amounts of money into “philanthropy”.

Class warfare and the resulting severe inequality are carefully planned by the billionaires of the world, and they keep winning, year after year.

THIS!!! Please read Warren Mosler’s 7 Deadly Innocent Frauds, it’s a short and easily readable free book intended for the masses.

From early monetary experiments in the colonies to Franklin’s paper money to Lincoln’s Civil War Greenback to Marriner Stoddard Eccles, economics could be the greatest American legacy of freedom and equality for humanity…if the masses only understood it.

Marriner Stoddard Eccles:

http://archive.sltrib.com/story.php?ref=/sltrib/opinion/51046418-82/eccles-economy-president-federal.html.csp

Germany doesn’t have balanced trade with Greece or other countries in the Eurozone. It’s basically hoovering up the surplus. But there’s no federal government to the Eurozone, so there’s no fiscal apparatus to recycle the surplus that’s been hoovered up by Germany, to redistribute it back to the states in the Eurozone. So instead, the troika props up the states of the EZ with loans.

Think of how well the US would hang together if the Fed Gov propped up the states with loans instead of fiscal spending.

You should not have suggested that.

Budgets are moral documents.

We’re spending 19% of GDP (30+ % in the Fed budget??? No, that can’t be right…) on health care. I’d call that lots of things but I’m not sure moral would be one of them.

fixhc.org !

Health care or health insurance? The two are not the same thing. Budgeting no money for that doesn’t fix the problem and makes a statement on how the budget makers’ value people’s health.

What % on prisons? Military? Domestic spying? bank bailouts?

Cherry picking one doesn’t leave any context.

Speaking of austerity check out this interview with Trump’s budget director Trump’s budget director on what’s on, and off, the table for cuts

I think he meant to say that it doesn’t increase spending. Basically a voluntary sequester. Or it could be even worse – if they want to be deficit neutral when reducing taxes, then they would have to reduce spending.

Can tell these guys are chomping at the bits for cuts to entitlements too

As well as safety net in general

Survival of the fittest.

They don’t want to eliminate those programs. They want to privatise the programs, and the way to enable that is to threaten to eliminate them.

I’m waiting for Haygood to come along and tell us there hasn’t been any actual austerity post-2008.

Massive Keynesian stimulus as everyone knows…. printing free money ™ thingy….

Delusions’ of value must never occur where inflation is pure ev’bal…. especially wages…

disheveled…. thievery…

“Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea” by Mark Blyth. You’re welcome.

Mark Blyth is a “political scientist” (there is actually no such thing as political science), not an economist. He has made far too many factually false assertions.

Arguments, please.

I do not argue, but merely point out facts, which are much easier (though not necessarily easy) to evaluate.

Mark Blyth is a fast talker, but spends a lot time talking about what everybody else said, not what he thinks is true. A lot of what he said on his YouTube video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQuHSQXxsjM

is commonly accepted (though not necessarily, and improbably, true).

For example, he said (about 5 min in the video) that in the Great Recession, “there was no orgy of public spending – it was a lie”. Then, he changed his mind and said that if there were an orgy of public spending it was to bail out the banks and on “income protection and asset protection for people who had made out the most in the past 30 years”.

So he was saying some government spending is counted as public spending, while other government spending does not count as public spending – truly muddled thinking on display.

I agree that a lot of public spending (in trillions) was misdirected and counter-productive, but it was still an orgy of public spending and is probably intrinsic to the nature of public spending, because it is generally unaccountable and wasteful spending of other people’s money.

It seems to me that the analysis misses the point of why to implement austerity and so it provides evidence that austerity lead to results that are generally bad but that are not exactly relevant to the reason to implement austerity.

The reason to implement austerity (== cut in gov’t expenses and increased tax rates) is to make sure that gov’t debt and its interest are paid exactly as promised under contract. So less GDP growth, less investment, and less inflation are all potentially important but ancillary issues. Even the ratio of debt to GDP is not exactly relevant if the fall in GDP is not discounted from the increase in that ratio as a result of austerity.

The real question is: given the recessionary shock would the gov’ts of the countries affected have been able to pay interest on their debts as promised under contract if austerity was not implemented? This is the quantity that should have been modeled by the scenarios in Fig. 2.

For instance consider Spain. One third of the national budget, the second biggest item (after pensions), is destined to pay interest of its debt. Without cutting expenses and without tax hikes (i.e. without austerity) would the Spanish gov’t be able to allocate that much of its income (in absolute numbers, not divided by GDP) to honor its contracts with lenders?

The definition and measurement of austerity are unscientific, because they are not objective or independent of theory. Projected or expected government spending is dependent on models and theories which may be (and almost certainly) wrong from forecasting track records. Hence the measure of austerity used in this paper is merely a measure of forecasting errors. In other words, the paper merely states that forecasting errors of government spending is correlated with forecasting errors of GDP growth rates. Duh. The paper says nothing useful about austerity!

Abuse of language. How is austerity defined? Austerity is when a government runs a budget surplus, otherwise a government budget deficit is considered economic stimulus.

Since most governments have been running budget deficits most of the time, there has never been much austerity. As a matter of fact, the US government has been running nearly permanent budget deficits for decades providing continuous stimulus, except for the last few Clinton years of budget surpluses which were associated with strong economic growth.

These days, a reduction in government budget deficit is considered “austerity”, in an abuse of language. Running budget deficits, large or small, cannot be called austerity. There has never been austerity before, during or after the Great Recession; the slow economic recovery in Europe, US and elsewhere is due to continued wasteful government spending.

http://www.asepp.com/fiscal-stimulus-of-consumption/

I’m afraid that you’re missing the point. Spending cuts motivated by a desire to cut spending, and with no heed paid to what publicly funded service or investment you’re cutting, because all that matters to you is reducing the size of the number associated with govt spending, is bad policy. Doing so in a time when private enterprise, nor private consumption, nor foreign demand can make up the difference will lead to (increased) unemployment / loss of aggregate income (and thus demand) and through that, a (deeper) recession.

Government deficits aren’t inherently bad (nor good); you must look at the state of society to see whether there is slack / problems that cannot be fixed by private or local initiatives, and then how the govt can help that. What’s happening now is the opposite — politicians are cutting govt spending without caring what that does to society, simply because they and the people who they are beholden to want to cut public services (except the ones they like — such as military spending, subsidies for big ag, etc.)

Would really recommend you take 25 or so mins to watch this conversation/interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JGuNpqYBkZk

I’m afraid that you’re missing the point. Theoretically, I agree that “government deficits aren’t inherently bad (nor good)”.

You are talking about theory, whereas I’m talking about facts. Of course, one could imagine a wise government or dictator (e.g. Lee Kwan Yew) who could do a lot of good for their country, but the historical data indicate a very low probability. There are theories for why this has been the case (not necessarily correct), such as public choice theory of Buchanan, Tulloch, Olsen etc. Large governments, as defined by large government expenditure as a percent of GDP, are bad news for their economies.

http://www.asepp.com/capitalism-economic-growth/

Modern money theory (MMT) and Warren Mosler are full of unscientific fallacies. Their explanation for sovereign state defaulting on their debt is that they don’t understand the magic of MMT! There are no such things as hyperinflation and currency collapse in MMT. The problems of Venezuela are caused by not knowing or understanding MMT! Central banks are unnecessary for money creation according to MMT! Governments should just issue money themselves, no need for central banks. Blah, blah, blah. They have a very limited understanding of the real world.

Economic education is a debt-financed lobotomy.

Not speaking as an economist but I would bet that whether a government deficit is good or bad for a country depends on a couple of things: what the money was spent on and your revenue collection decisions.

If your deficit is used building up useful infrastructure, enhancing the lives of your citizens, and broad based research and development your country’s GDP will be enhanced. IF your deficit is based on massive spending in limited areas where the grift is high and little or nothing improves in the lives of the common, where the richest receive the greatest largesse from the government in spending and benefits there will be little or no advantage to the country’s economic life.

Funnily enough our biggest proponents of ‘austerity’ are fine with government spending that enhances their bottom lines, be it the MIC, our oversize Financial Industry, or even more disturbing our political class who now fairly openly trade government services for private benefit. They ignore the point that when we were spending money on domestic infrastructure, education, scientific research and yes SS and Medicare our GDP was much healthier than it is today. Mind you there were also less incentives in our tax code to encourage our richest folk to move jobs out of America, hoard their cash or pretend that gambling on the stock and bond markets was ‘investment’ than we currently have and that also helped.

A vibrant train and transportation system, a well funded education system (where the idea of grade schools with class sizes of 30 or more would be repugnant) which values craft and trade work as well as ‘professional’ and business education, a post office with a postal bank not under attack, well funded renewable energy programs, space programs, research programs, arts programs and yes Medicare for All and expanded Social Security, would actually be investments in our economic health far beyond most of what we concentrate on today. And while there would be things that you can less clearly trace economic benefits – like cleaning up our water systems, really working to clean up toxic spaces and clear support of rehab and mental health programs, our parks, etc – it would still be of far more benefit to the well being of the nation than building the umpteenth missile or funding the enemy of our oligarchs’ selected enemies.

Austerity for public good while there is still largely unlimited funds for the MIC, corporate low wage government backstop, Financial Industry hidden supports, and large bureaucratic grift will only mean a lagging GDP with even less government income (because all this comes with more and more tax cuts for those who are the only ones making out in these false economies) Thus furthering the supposed need for austerity. And we will continue the loop by doubling down on cutting the things that really do grow the economy – like food benefits for hungry poor Americans. And yes I realize the irony that little piece of corporate welfare for places like Walmart which refuse to pay large numbers of their employees a living wage actually support Walmart along with farmers and food production companies is a better driver of the economy than much else we do. Yes it still adds more to our economic health than the Pentagon slush fund.

And ultimately this is the point – it isn’t whether MMT is right or wrong, it is all theory because no one is trying it. What we know does not work is austerity as it currently practiced – because we have a whole lot of evidence for it. It has been tried. Austerity for the public good but not for selected corporate darlings, tax cuts for the rich and outsized corporations, globalization and financial deregulation lend themselves to increasing deficits, a shrinking economy except for bubbles, massive income inequality and yes theft and corruption. It is long past time to tell anyone who screams about the deficit to sit down, shut up and get the frack out of the way, before doing pretty much the opposite of everything they recommend.

Blanket statements such as “Large governments, as defined by large government expenditure as a percent of GDP,” are really meaningless. Are you really saying that the creation of the WPA in/around 1936 was “bad for the economy”? That the command economy that could be found in the US once they decided to enter the War was “bad”? What does it even mean to say that?

hyperinflation and currency collapse are both perfectly explainable using an MMT framework, so I’m afraid that you’ve been misinformed on this point (see Randy Wray’s 7-part intro https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLkKoAQeawlO64sZ7KuRp21luMaUM63guo for an exhaustive introduction to MMT); moreover, as Mark Blyth, wearing his academician’s hat, notes here (and I’m sure he’s published on it): weimar hyperinflation was deliberately created by politicians who wanted to stick it to France: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yWsMfmNXUYQ

As for your remarks about money creation: the sovereign decides who is allowed to issue, print or lend money. Parliament can choose to make this happen via a CB, but that’s always a choice — ideally one informed by reality, but we don’t seem to live in a world where that counts for much. Any money issued without legal permission is by definition fake, or fraudulently created. So you can talk about how this misapprehends reality, but I really don’t see what that means.

“That the command economy that could be found in the US once they decided to enter the War was “bad”?”

Definitely bad. If you don’t know this (like most economists), you are a victim of the “war is good for the economy” fallacy.

You’re missing the forest for the trees — “Good for the economy” is only meaningful in the context of what’s socially desirable. In the context of a world in which the choice is German domination or a commandeering of the economy, a choice was made that the former was worse than the latter. Now, I completely agree that in most cases, we shouldn’t want to give these enormous amounts of money to the MIC. But if a group of people agrees that it is desirable to do so, it makes no sense to say “but that’s bad because govt would become big, and that is worse than letting Hitler conquer us”.

I don’t use value-laden concepts such as socially desirable without precise definition – who defines what’s socially desirable?

I define a bad economic policy (e.g. larger governments) as one which leads eventually to Keynesian economic collapse:

http://www.asepp.com/keynesian-fallacy-collapse/

We are well on our way, including world war as a misguided economic stimulus.

As Keynes said, in the long run, we’re all dead. The question is who gets to live how until we do. (And yes, I’d prefer no spending on wars.)

Goldbugs and Austrians, no matter how well-intentioned, promote a monetary system that will become or remain equally unequal as the current system is, because they too have no way to combat concentration of power, wealth, etc.

The gold standard, if strictly adhered to, prevents war.

When Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo, no one thought it would lead to a world war, because most countries were on the gold standard and therefore could not afford wars, so it was thought.

Of course, the gold standard was quickly abandoned to permit governments the freedom to print fiat currency, as happened many times throughout the history of conflict. Citizens were coerced into having their purchasing power stolen, suffered real austerity, food rations, scarcity of almost everything, reduced consumption and lower standards of living, not to mention sacrificing their lives.

They were the times of equality, equality in poverty, as was the fate of totalitarian, communist and socialist states, virtually without exception. Not everyone was poor however, as there were tiny fractions of elites who lived lives of privilege and luxury. Such states ultimately collapsed, because they were not economically sustainable.

The fiat currency system, endorsed by MMT, is the monetary path to the same socialist state and we are already well on our way there. MMT teaches governments nothing that they don’t already know. Today, the main difference compared to the past is that the elite is not just big government, the elite includes also big banks and big business in collusion with big government.

War is a means of imposing real austerity, increasing economic output through the military-industrial complex and enforcing strict control over dissent and the population. This austerity is coming.

“I don’t use value-laden concepts such as socially desirable without precise definition – who defines what’s socially desirable?”

That’s a good habit, but my hypothetical wasn’t intended as a claim about how that decision came about historically — it was an attempt to make it clear that ideas about “economic desirability” are only part of the puzzle, and that it is equally problematic to “precisely define” “good economic policy” as it is to define good social policy — all such terms are defined in relation to each other.

“Large government is defined by large government expenditure as a percent of GDP”: how it that meaningless? You should read the blog post:

http://www.asepp.com/capitalism-economic-growth/

On money creation, you said:

“Parliament can choose to make this happen via a CB, but that’s always a choice — ideally one informed by reality, but we don’t seem to live in a world where that counts for much.”

You and MMT would say the debate about US government debt and the debt ceiling is just ignorant people fussing over nothing – they just don’t understand MMT!!!

No, I’d say — riffing on Mosler — that a debt-ceiling is a particularly stupid self-imposed constraint. They’re not fussing over nothing though — the constraint exists because reactionaries want to have “reasons” to “cut spending”.