Yves here. This post indirectly makes a powerful case for automatic stabilizers, as in programs like food stamps and other social safety nets, where spending automatically rises in bad times and falls off when the economy is robust. You don’t need economists intervening as much if government spending levels auto-correct.

By Richard Alford, a former New York Fed economist. Since then, he has worked in the financial industry as a trading floor economist and strategist on both the sell side and the buy side

Forecasting is a necessary component of macroeconomic policy formation for the simple reason that macroeconomic policies act with “long and variable lags.” If policy is based upon a macroeconomic forecast that proves to be inaccurate, then the policy prescription will become inappropriate over the forecast horizon and degrade economic performance. Consequently, understanding the odds and possible impact of forecasting error should be a important element of policy design.

This post assesses the success of both private and official sources in forecasting turning points in the economy, which is one way to evaluate risks to the forecasts and policy. It concludes the experts don’t do a good job. It then addresses whether this failure matters, that is, whether the ability to forecast turning points in the economy is a sound benchmark. The post closes with a number of implications of the inability to forecast turning points for macroeconomic policy.

The Forecasting Record: Bad to Ugly

The macroeconomic record of forecasting turning points is poor, as illustrated in: “There Will Be Growth in the Spring”: How Well do Economists Predict Turning Points?, by Hites Ahir and Prakash Loungani (VoxEu April 2014):

In a classic 1987 paper, William Nordhaus documented that, as forecasters, we tend to break the “bad news to ourselves slowly, taking too long to allow surprises to be incorporated into our forecasts.” Papers by Herman Stekler (1972) and Victor Zarnowitz (1986) found that forecasters had missed every turning point in the US economy.

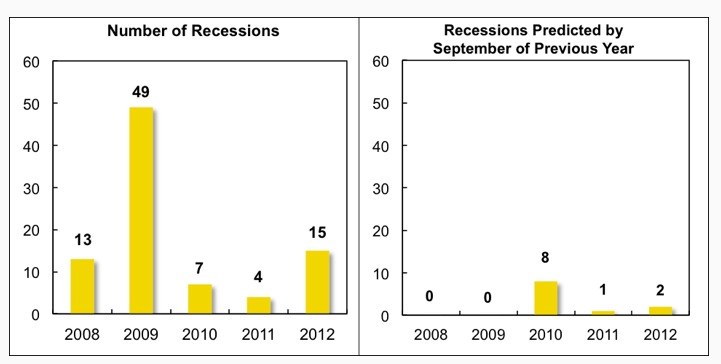

These traits appear to have persisted to this day. In our recent work we look at the record of professional forecasters in predicting recessions over the period 2008-2012 (Ahir and Loungani 2014). There were a total of 88 recessions over this period, where a recession is defined as a year “in which real GDP fell on a year-over-year basis in a given country. The distribution of recessions over the different years is shown in the left-hand panel of Figure1.Figure 1. Number of recessions predicted by September of the previous year

The panel on the right shows the number of cases in which forecasters predicted a fall in real GDP by September of the preceding year. These predictions come from Consensus Forecasts, which provides for each country the real GDP forecasts of a number of prominent economic analysts and reports the individual forecasts as well as simple statistics such as the mean (the consensus).

As shown above, none of the 62 recessions in 2008–09 was predicted as the previous year was drawing to a close. However, once the full realisation of the magnitude and breadth of the Great Recession became known, forecasters did predict by September 2009 that eight countries would be in recession in 2010, which turned out to be the right call in three of these cases. But the recessions in 2011–12 again came largely as a surprise to forecasters…

In short, the ability of forecasters to predict turning points appears limited. This finding holds up to a number of robustness checks…To summarise, the evidence over the past two decades supports the view that “the record of failure to predict recessions is virtually unblemished,” as Loungani (2001) concluded based on the evidence of the 1990s.

The results presented in the VoxEu post indicate that official forecasts are no better than private sector forecasts:

Forecasts from the official sector, either from national sources or international agencies, are no better at predicting turning points. In the case of the US, the March 2007 statement by then-Fed Chairman Bernanke that “the impact on the broader economy and financial markets of the problems in the subprime market seems likely to be contained” has received a lot of attention. Another Fed Chair, Alan Greenspan, told his colleagues in late-August 1990 – a month into a recession – that “those who argue that we are already in a recession are reasonably certain to be wrong.” Forecasts by Fed staff have also missed turning points, as discussed in Sinclair, Joutz and Stekler (2010).

During the Great Recession, Consensus forecasts and official sector forecasts were so similar that statistical horse races to assess which one did better end up in a photo-finish.”

Is Correctly Identifying Turning Points a Useful Benchmark for Macroeconomic Forecasts?

Most evaluations of the accuracy of macroeconomic forecasts are based on comparisons of measures of the average absolute size of the forecast errors. However, the number of periods in which the economy is trending far exceeds the number of periods in which the economy is turning. Consequently, evaluations of forecast accuracy based on average errors place a low weight on the accuracy of forecasts at turning points. Macroeconomic policy was developed to reduce the incidence and costs of significant deviations from full employment, not relatively small quarter-to-quarter deviations from trend. Hence, the ability to forecast turning points in the economic cycle is a more appropriate measure of forecast accuracy for setting macroeconomic policy than is the average error over a cycle or cycles.

What Are the Implications of the Inability of Forecasts to Identify Turning Points?

In addition to all the other risks that economic agents face, the inability to forecast turning points implies that economic agents must also contend with 1) the risks inherent in the economy, and 2) the risk that they will incorrectly forecast the future course of policy. Given the dynamic and complex nature of a modern economy, economic agents and policymakers themselves also face the risk that policymakers will at times set policy inappropriately. However, there is little evidence that policymakers consider and communicate to the markets the existence of the possibility of outcomes removed from the central tendency of their forecasts.

While macro policy mistakes are inevitable, the costs of policy mistakes can be minimized if policymakers continuously and diligently explore the risk that their models are mis-specified, the forecasts are incorrect, and policies are inappropriate. This is not to say that policymakers should alternate between slamming on the brakes and flooring the accelerator, but rather be willing to alter the policy more quickly when developments change the confidence in the forecast and/or the risk/return profile of the policy stance.

To be successful in the long-run, policymakers must be comfortable making decisions despite the risks and uncertainty. They must also have the flexibility to adjust policy in light of 1) new evidence that the economy is not evolving as expected, 2) in response to risks not previously appreciated, or 3) changes in the structure of the economy or sectors that increase the probability that the underlying model is mis-specified. They must constantly weigh the risk/return profiles of alternative policy paths and consider all possible outcomes and not just the most likely.

Unfortunately, policymakers have been anything but open minded about the possibility that their underlying model is mis-specified and their forecast and policy decisions are incorrect. The rude and anti-intellectual response of the attendees at the Jackson Hole symposium in 2005 to Rajan’s presentation (“Has Financial Development Made the World Riskier?”) is just one example.

It is also clear that the Fed never explored the downside risks to its chosen policy path prior to the crisis of 2007. The civilian unemployment rate peaked at 6.2% in July of 2003. The upside potential to the continuance of the accommodative policy stance, as reflected in the elevated unemployment rate, declined rather steadily. In 2004, with the unemployment rate at 5.6%, the Fed started to raise the Fed funds rate from 1% at a “measured pace,” i.e., 25 basis points per FOMC meeting. By May of 2005, the unemployment rate was 5.1%, down 1.1 percentage points from its peak in June of 2003. The upside potential to the continuation of the accommodative stance had been halved. (This assumes that the Fed viewed the 4.2% unemployment rate as close to its estimate of NAIRU — the Fed funds rate plateaued at 5.25% in 2006 when the unemployment rate was 4.2%.)

What was happening to the downside risks? The Fed acted as if there were no downside risks and dismissed any and every argument that economic and financial fragilities and unsustainabilities were building. Post-crisis, the Fed defended its failure to see the crisis and recession by arguing that no one saw it coming. However, numerous parties cited risks, including Shiller and Rajan. Most telling, Fed Governor Kohn gave a speech in 2003 in which he cited and dismissed criticisms of Fed policy, including the possibility of financial dislocations stemming from a correction in the housing market.

Unfortunately, economic and financial fragilities and unsustainabilities were building. The rate of house price appreciation was accelerating, loan-to-value ratios were rising, financial institutions were becoming increasingly leveraged and were employing CDS and other off-balance sheet vehicles, corporate bonds were becoming covenant light (reduced investor protections), and investors were reaching for yield.

The housing market rolled over in 2006 and eventually took with it the balance sheets of households and financial institutions, as well as the performance of the real economy. The unemployment rate rose, reaching 10% in October of 2008, despite monetary and fiscal stimulus. While the precise size, depth and duration of the recession was unknowable in advance, one does not have to have foreseen its severity to have realized that the risk/return profile associated with the policy stance had deteriorated and become unfavorable long before the Fed funds rate ceased to be accommodative.

An ex post, and hence somewhat unfair exploration sheds light on the deterioration of the risk/return profile. The Fed pursued an accommodative policy through 2005 when the possible return (upside potential) was a 1 percentage point decline in the unemployment rate and the downside risk was at least an unemployment rate 6 percentage points higher than the target the Fed was aiming for. To risk losing 6 when the best you can do is gain 1 does not make a lot of sense, unless one has done all his or her homework and is very confident of a favorable outcome

The Fed was very confident, but hadn’t done its homework. Perhaps the failure to forecast or to allow for even the possibility of a housing price bubble and financial crisis reflected its chosen intellectual framework, i.e., DSGE models. The financial sector was excluded from DSGE models, as it was viewed as a passive intermediary between the representative agents, and of no macroeconomic importance itself. While the assumed absence of a financial sector presumably aided in the construction and tractability of the DSGE models, the question remains: how did models with no financial sector come to dominate policymaking at the Fed and other central banks? After all, in 2006, the market capitalization of firms in the financial sector was 22.3 % of the total market capitalization of the S&P 500. Employment by the financial sector was 7+% of all private sector employment. The scale of the profits and the number of jobs in the sector make it difficult to believe that it was a passive intermediary of no macroeconomic significance. Furthermore, history is replete with instances of financial disruptions being followed by unusually long and deep recessions, e.g., Japan’s lost decades and the US Great Depression.

Nonetheless, the Fed never took warnings about the financial risks seriously. The Fed’s surprise at the crisis and recession reflect its failure to fully research and understand the implications of its policies, both macroeconomic and regulatory. It blithely assumed that the announced low-for-long accommodative monetary policy was a scalpel with narrowly defined implications for the real economy, when, as it turned out, it was a relatively blunt instrument with implications for the stability of the financial markets as well the real economy.

The results cited in the VoxEu blog post also raise questions about the wisdom of central bank commitments to policies of “expectations management” and “forward guidance”. The term “expectations management” is an example of Orwellian Newspeak. “Expectations management” is an exercise in expectations (thought?) control, i.e., the Fed uses policy commitments to cause the range of alternative private forecasts of policy and the real economy to converge with its own.

There are a number of problems and risks. The official forecasts are no better at identifying turning points than are the private forecasts that they replace. Expectations management can exacerbate real economic problems if it succeeds in replacing alternative forecasts when its own underlying forecast is incorrect. For example, the Fed succeeded in convincing people post-2000 that: 1) policy was responsible for the advent of the “Great Moderation” and insured continued trend growth with low and stable rates of interest and inflation, 2) housing prices were not in a “bubble”, and 3) critics who saw the possibility of future financial and economic problems were incorrect.

In doing so, Fed encouraged the increased use of leverage and the willingness to incur higher ratios of debt to income. As a result, it contributed to the economic and financial fragilities, the scale of the economic and financial dislocation that followed the crisis, as well as the financial and economic hardship experienced by a large number of households.

The Fed also argues strongly that the use of talk as policy has had beneficial effects. The “talk” has had easily observable effects on the financial markets. However, it is not clear if the developments in the financial markets have been the result of increased policy transparency or of decreased near-term policy uncertainty.

“Forward guidance,” a commitment to a predetermined policy path has been cited as particularly effective, even though it is less transparent than a rule-based policy path, e.g., the Taylor Rule. The Taylor Rule mechanically linked changes in specified variables to the policy response. In contrast, forward guidance has been a litany of short-lived commitments. In addition, the rationale for the purchases of $85B (as opposed to say $125B or $60B) per month of Treasuries and MBS was never disclosed. Neither was the rationale underlying the decision about the pace at which to taper the purchases. In the absence of an underlying rationale for the chosen path, markets are without a benchmark to evaluate the policy or to form expectations for policy for the periods after the commitment expires.

However, the commitment to a path for policy has trumped the opaqueness of policy as the asset markets have rallied. It appears that the commitment to a particular path for policy in the near-term reduces the uncertainty for players in the financial markets and therefore increases the incentive to employ leverage maturity mis-matches and to reach for yield. Hence, “forward guidance” has the ability to generate responses in the financial markets even in the absence of policy transparency. The beneficial effects on the real economy are less certain, as are the implications for financial stability and the sustainability of real growth.

Also, on an internal logic consistency note, it is more than a little ironic that while the Fed embraces models that assume that markets exhibit ‘rational’ expectations, it also argues that it has to actively and almost continuously change market expectations about policy. If the market is incapable of correctly, i.e., rationally, interpreting a carefully worded FOMC statement, what is the chance that the market’s other expectations, based on noisy and often conflicting data, are “rational.”

Conclusions

The historical track record of macroeconomic forecasting, including the recent past, is inconsistent with the degree of confidence expressed by official and private forecasters. In evaluating macroeconomic forecasts and resulting policy prescriptions, one should employ a healthy dose of skepticism. The size of the dose should vary directly with the precision of the forecast, the expressed confidence of the forecaster and the degree of commitment that the forecaster has shown to a model or school of thought.

Furthermore, committing to follow a predefined path for policy for an extended period of time, even if one is highly confident, is risky. If the underlying forecast is accurate and the policy correct, the upside potential will be realized. If, however, the forecast is not accurate or the policy has unforeseen and undesirable side effects, the commitment to the policy is likely to increase the costs attached to the adoption of that policy.

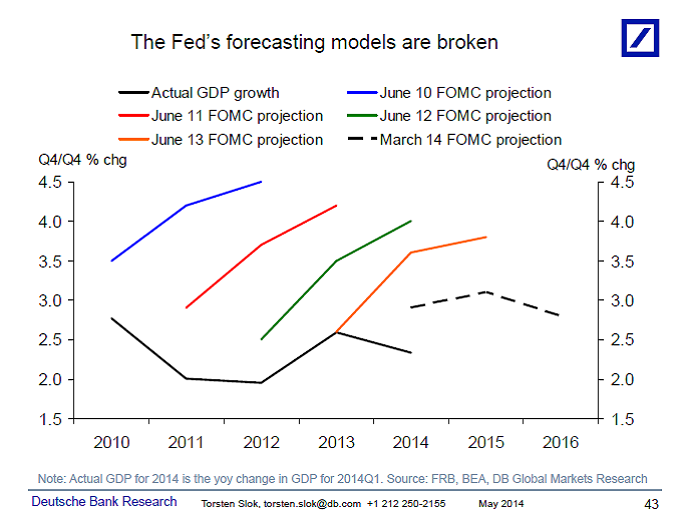

While the Fed talks as if it knows the outcomes of its policy choices with a differentially higher degree of certainty, the record indicates that it doesn’t:

Policymakers should adopt disciplines that reflect the inherent riskiness in setting policy. There are numerous disciplines that involve decision making in the face of risk and uncertainty, e.g., game theory. Perhaps policymakers should consider incorporating findings from those fields in to policy design and implementation, rather than setting policy as if they know with certainty the future course of the real economy and the interactions among policy, the financial markets and the real economy.

The weather reports do better.

I’m not sure what the issue is here. Aren’t they paid to lie?

You missed the point! They believe their bullshit and base policy on it. That is much worse because someone who knows they are lying might change course when caught out. If you believe your bullshit, you won’t change course, in fact, you’ll try to deny what is before your eyes (witness the Fed and how long it has taken them to recognize that ZIRP and QE aren’t doing what they’d convinced themselves that they would do).

That was one of the scary things I finally figured out during my last visit to DC. I thought people constructed policy first and then reduced it to soundbites to sell it. I came to realize that most people in DC reason from soundbites (as in their analysis and policy design is constructed from soundbites from the get-go).

And indeed we know from where those soundbites emanate … The bankster arm of the government, the privately owned and operated Federal Reserve … And any economist that doesn’t stay “on key” is soon marginalized.

Yes Yves, give us the ‘honest liar’ who will go with the flow ahead of the deluded true believer. I’ve seen 20 years of the last part of your comment, plus years of attending development conferences hearing textbook blather from experts with a thesaurus. I suspect this is just one case of wider problems with “expert knowledge” that could be embodied in machine. The politicians are clearly half-wits using a language of control. We could have something much closer to project action instead of the monetary and fiscal stuff – something that would adjust to action outcomes (like a trading block jobs scheme being implemented) that treat people as important and fix the money through real-time evaluation.

Maybe the biggest question is why people apparently so smart are actually so stupid. We have research on these ‘r’ factors. I prefer Labov (60s) who pointed out your average Ivy League graduate is as thick as mud and can only regurgitate from set texts, being useless on practical reasoning.

Realists and pessimists rarely climb the corporate ladder. Those who do are usually some indispensable right hand who diligently manage how they present themselves. And even then, I’ve witnessed some dramatic breakups at key points.

From what I’ve seen where I work, the people who go from clerks to management are nothing more than glorified order takers. These big corporations should be grateful that everything is so weighed in their favour that they are guaranteed to make money no matter how incompetent they are. Thus they don’t need free thinking, intelligent people running the business. They only need team players who won’t rock the boat. Such corporations would never survive in a true free market economy. But who needs that when they can buy all the lawmakers?

Funny that if I posted the above at FB and mentioned my company name I could be fired. Quite the world we’ve created! Small wonder most people prefer to believe all the lies and the grand illusion.

It’s the guarantee that failure will not be punished the makes this mindset possible. In my field, military history, generals and admirals cannot in a competitive situation delude themselves about actual conditions or likely outcomes. Those that do get smashed. But in a Vietnam or Iraq type situation, where the enemy is never going to be strong enough to destroy your main force or kick your ass back to San Diego or Tampa (CENTCOM HQ, if you are curious why I picked Tampa) you can have the “5 o’clock follies” and delude yourself to your heart’s content. And, the more delusional your “light at the end of the tunnel” rhetoric, the more your political masters will love and reward you!

America has been so rich and powerful for so long now that making shit up, because there are no serious consequences for those who make the shit up, has become a way of life for our elites and their policy wonks. They are flabby-minded, and as Yves said, think in soundbites because all the incentives are to tell those with power and money what they want to hear and against those who would cast about reality and report what is actually happening. Only after a series of disasters that directly hurt the elite will truth-telling suddenly become popular (and in certain cultures, perhaps even this one, that day never comes–elites would rather go down to destruction than face an unwanted reality).

Great comment, James.

Truth telling in a culture based on denial and fantasy is always punished not just in formal organizations but in most social situations. Certainly the truth should, at times, be sugar coated or expressed creatively and artistically but today we need it in all its forms–we have no other rational course.

Short-termism is the optimist’s friend and realist’s and pessimist’s enemy.

Intelligence comes from the ability to think and especially to question oneself. Aren’t Ivy Leagers above that?

Those who major in economics may well be.

“your average Ivy League graduate is as thick as mud and can only regurgitate from set texts” To survive in an exchange economy, one must learn to trade (something): Ivy League liberal education teaches students to trade arguments.

Superficial people for a superficial society. Square pegs but are the holes square too?

One of the unique things about Americans particularly those at the top of their fields is that as they rise there is a tendency to lie more and their ability to rise is often dependent on their ability to pull the wool over their own eyes. American enterprise at all levels requires sincerity and sincerity depends on believing your own sales pitch.

And that’s about all that needs to be said.

Any economist in a policy making position today is a sycophant of the privately owned and operated Federal Reserve. This all starts in college where any student bucking Fed policy is quickly and surely isolated and discredited.

As for “professional” economists, professors or those that work in the private sector the game is the same … your papers will not be published or your services will be terminated upon any question of Fed omnipotence.

The economists that are policy makers today are Fed toadies for fear of their careers. It has only been a few tenured professors that challenge the Fed and they are only heard because of the reach of the internet …

A dated but explicit story:

Priceless: How The Federal Reserve Bought The Economics Profession

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/09/07/priceless-how-the-federal_n_278805.html

Priceless: How The Federal Reserve Bought The Economics Profession

The Federal Reserve, through its extensive network of consultants, visiting scholars, alumni and staff economists, so thoroughly dominates the field of economics that real criticism of the central bank has become a career liability for members of the profession, an investigation by the Huffington Post has found.

This dominance helps explain how, even after the Fed failed to foresee the greatest economic collapse since the Great Depression, the central bank has largely escaped criticism from academic economists. In the Fed’s thrall, the economists missed it, too.

“The Fed has a lock on the economics world,” says Joshua Rosner, a Wall Street analyst who correctly called the meltdown. “There is no room for other views, which I guess is why economists got it so wrong.”

There’s much much more …

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/09/07/priceless-how-the-federal_n_278805.html

As for “professional” economists, professors or those that work in the private sector the game is the same … your papers will not be published or your services will be terminated upon any question of Fed omnipotence.

That’s not true. The Fed’s research division routinely produces work that questions or contradicts basic assumptions underlying its policies, just as the IMF’s research division has undermined the economic reasoning behind the IMF’s austerity policies. That work is simply ignored.

“That work is simply ignored.”

And so are the economists that produced that work … especially when it comes to promotions and renewing contracts …

Plenty of economists working for the Fed publish work that contradicts key assumptions, and they spend their careers at the central bank. It simply isn’t correct to say the Fed will “getcha” if you do anything the governors don’t like because it isn’t an atmosphere of enforced orthodoxy, it’s an atmosphere of ideological blindness at the policy level.

There isn’t much real debate Ben. You’re right a few contrary papers emerge from time to time, but these still tend to be functionalist, singing from the same spreadsheet. Given the amount of money spent one might expect at least a full-employment simulation. Most of the work is very dull.

Frankly, this is as bad as the guy costing apology yesterday. The “insights” of Dr. Strangelove’s game ain’t. Yet knowing macro-forecasts are dud, let’s use some more computing power to put things right. Most people I know in this trade say stuff like, “Game theory does not offer any specific answers to any specific situation. It says something like these are the things to take into account”. One recent paper (2005) ends: “While further research is needed in order to identify whether there are situations for which game-theoretic analysis is more useful than other methods, current evidence suggests that decision makers would be wise to prefer forecasts from simulated interaction”.

It is typical of the technocrats or functionalists to only allow minor change they still control., rather than admit to genuine open enquiry. Deeper questions involve whether the forecasts themselves are of any interest or, say, just government covering it’s ass with apparent due process. There may be a case for doing away with forecasting and doing something more real-time – maybe control theory based – to discover more about the structure of the interactions in the economy and see if we can find nodes for intervention as we go along – or maybe just stop doing it. Is anyone asking ‘what benefit do we get from that spend’? Whether Anaplan could do it? And why should we care when they have no model for investment other than giving it to banks and the rich to squander?

“And why should we care when they have no model for investment other than giving it to banks and the rich to squander?” An excellent question, to which nobody seems to have a decent answer.

I fear many well-intentioned folks think it is possible to force looters and hoarders to help society by investing their money in ways that benefit everyone. The problem is that very rich folks can afford to pay very clever folks who will always devise ways to thwart this through regulatory capture, political corruption, etc. A better, more humane capitalism will never emerge since the entire system is driven by selfish greed– at best, a few servants of the super-rich will benefit from enjoying their status as merely affluent. They will rationalize their part in oppressing the poor by emphasizing their desire for reform, but won’t abandon this insane, murderous greed-based system even after decades of increasing misery for all except the super-rich and their well-compensated servants.

But how do we get around the bullet-proof example of Soviet economic planning leading to distortions, errors, and flat-out disasters? Because the answer to “dump the money on the rich and the private banks and let them sort it out via the Holy Market” is very likely “use public institutions to channel the money to productive investment.” And the retort is, “How well did that work under Soviet Communism, smart ass???”

Another answer, of course, would be “put the money into the hands of the lower 80% of earners with high marginal propensities to spend, and let them send signals to the markets about where they want the money invested”, but in a consumer culture run amok, the signals are not going to go where many of us think they should. They’ll go into keeping our wasteful, suburban, oil-dependent lifestyle running until peak oil and global warming destroys our civilization. And yes, I know this opens me to the feared “Who are YOU to think that you know better than Mr. and Mrs. American Consumer?!? Oh, the arrogance of these intellectual elitists!!!” (harrumph, harrumph, harrumph) attack.

We need a strategy to get around the “Communism failed so planning is worthless” and the “who are you to tell me I can’t live in a poorly insulated 5000 square foot house and drive around in Denali if I want to” arguments, and I don’t see them, not ones with any emotional resonance. We’re fighting fear, avarice, and inertia here. What trumps those emotional states so that the logic of your message can get through?

Authoritarian systems, whether corporate capitalism as currently practiced in the U.S., or Stalinism as practiced in the old U.S.S.R, have pretty clearly demonstrated themselves to be failures.

This is why I am neither a capitalist nor a communist. I am an anarcho-syndicalist!!

“What trumps those emotional states so that the logic of your message can get through?”

If anything trumps those emotional states, it would probably have to be competing, more powerful emotional states. Logic follows decisions–it doesn’t lead them.

You got that right Uly. We may have to go a bit further than people investing “their money”. There is something peculiar in the term “investment” these days. Like I can understand breaking a bit of back with some mates clearing land will will live off as investment, but now investment seems to mean someone intercoursing the single Gaussian copula far away taking our clearing from under our feet.

I imagine Bill Black might point out that low interest rates are not necessary for the type of control fraud that we witnessed during the housing boom. While the Fed’s permissiveness no doubt helped things along, the S&L Crisis occurred during a period of high interest rates. The Fed’s inability to predict anything less certain than the morrow’s sunrise is a problem, for sure, but their inability/unwillingness to regulate is an even bigger one.

This is such a reasonable, wrong-headed post it is difficult to know where to begin. Forecasters and policymakers are not interested in accurate predictions. Their job is to produce and use theory and predictions to cover for looting by the rich and elites. They are in a word users and purveyors of propaganda. Do they believe their propaganda? As I have argued numerous times, it doesn’t matter. True believers act in bad faith all the time. On top of this, these true believers justify their system of privileges based on the demonstrably false assertion that they “know” better than the rest of us. You can not know better if you are wrong all the time. But then their system of privileges is not based on their being right but on serving the interests of those who fund and own them.

Again Alford assumes, wrongly, that the goal of policymakers and the Fed is to stabilize the economy, rather than abetting in its plundering.

His timeline for predictions is way too long and misunderstands the nature of turning points. When the housing bubble burst in August of 2007, I predicted shortly thereafter that the economy would go into recession –as it did in December of that year. But this prediction was based on A) awareness of the housing bubble, B) that barring any outside intervention to forestall the burst, the burst would occur, C) that the burst could have happened anytime 6-9 months from when it did, and D) the same inaction that allowed the formation and bursting of the bubble would continue. Given all this, the recession still could have happened a couple of months either side of when it did.

Alford lumps the meltdown into the recession originally sparked by the housing bust, but it really was a very different beast. It wasn’t just a bumpy stretch in the economy. It was something that threatened to take out the financial system itself. I remember spending a lot of 2008 eating virtual popcorn with other bloggers and wondering which event or series of events would push things over the edge. This was all based on our awareness of no pro-active policy to head off a meltdown and the realization that the conditions were in place for a collapse. So we watched the dominoes fall. But it wasn’t until a month or even a few weeks out that we really felt that things had entered a terminal phase. But even then, if Paulson, Bernanke, and Geithner had come up with some makeshift plan for Lehman, the crisis that hit in September 2008 could have been delayed weeks, possibly months. Indeed this is what we see now. Everything is in place for another bust, and it isn’t just us. It’s everyone. Europe, China, Japan, the BRICs, and developing markets, all are set to go. But we also see how governments, while not fixing the system (being agents of the kleptocrats they have no interest in fixing anything, i.e. stopping the looting), have been able to delay the next collapse for, depending upon the country or grouping, two to four years. At some point, someone will make a mistake or there will be an unforeseen or uncontrollable event, and it will all go kerblooey all over again. The point is we will not know or recognize the trigger until weeks before or after it goes off.

Other observations: Can we just call “reaching for yield” what it is, gambling, and more specifically doubling down on already dubious bets?

As for the Fed’s $85 billion a month in QE, that is rather simple. $85 billion X 12 = $1.020 trillion. Bernanke decided on a trillion dollars in QE per year, and $85 billion a month was the closest round number to achieve that goal.

Yesterday’s film at the library was “All The King’s Men”. A rather predictable movie but with great acting. It’s a shame we couldn’t at least be entertained by a Broderick Crawford, instead of the endless bad actors gracing our stage.

Crawford was a bit fat. That would rule him out in these enlightened, non-discriminating times. I take Hugh’s points. The purpose of these predictions, otherwise, would be such as planning current spend and activities as one would in a business plan. One tools up against the predicted demands/returns/on-costs and such. Business plans are notoriously inaccurate too. Of course, once one makes a prediction, someone totting up the future reality knows what the predictions were and probably has plenty of wiggle room in what he writes up. And maybe gets a little bored, hears of Craazyman’s pin and evaporation of workings technique, bags-off a stab and knows the language of seasonal adjustment and consolidation of accounts. All he has to do is not make a return that far off the “range”. Sooner or later, he can burn all his workings in a crash. The graduate employment destinations of one of my former universities was worked out by choosing what they would have been, if known at all given only 6 student responses, had the university been “average”. One suspects USUK plc works to the same method. One dropped decimal point by Craazyman and the sky falls. This actually happened in the UK when we went cap-in-hand to the IMF in 1976, believing ourselves skint when actually flush. The figures are probably manipulated up or down on whether a few elite bets are long or short crusted pork-belly futures.

Question: do they have the ability to delay the inevitable indefinitely? I’m asking, because I don’t know. Japan, Europe, and the United States should all have gone over an economic cliff on several different occasions. They have not, by which I mean in none of those countries has the economy gone into the tank the way it did in 1873 or 1929-31. Can they play this out, with a slowly lowering general standard of living, multiply times until peak oil, ecological disaster, and/or the next asteroid hits? Will the crack-up come before they’ve run through our global patrimony and there are not enough resources left to pick up the pieces? These seem to be the overriding critical questions of our time.

well my mathematically precise coment got eatin but here’s the literary version

The Doom &Gloom economists have predicted 3,498,289 of the last 3 recessions. Along with dollar collapse, the explosion of the Yellowstone park volcano and asterioid impact.

And they’re still forecasting, writing books, appearing on TV and raking in the cash!

See, it doesn’t matter whether your’re predictions are righte, it just matters if you’re the economist, the money flows your way

I appreciate the humor when making an excellent point…What sells is the “promise”, not the goods. How long would the eradication of cancer provide a cash stream to those who now “profit” from selling the “promise”? After decades, we’re still hearing a variation of “please donate to our research, we’re so close”. That ‘research’ seems mostly a re-packaging of the “promise”.

Hot Off The Wire

Yesterday Marc Faber predicted we get a crash worse than 2008 …..sometime soon.

Jimi Rogers says he won’t buy US stock – but Chinese and Russian stock look good. ‘Course he lives in Singapore now – so maybe he thinks the US won’t freeze his Russian stock portfolio.

On the other hand, WW3 could start in Eastern Europe. Looks like China may re-kindle WW2, and the Vietnam War over oil in the South [Japan, US] China Sea again.

And someone must be thinking doing WW1 again is a good idea – we just haven’t heard who yet.

But don’t fight the tape. Maybe load up on facebook and twitter as the new tech dynasty to carry the torch handed off from the Microsoft-Intel-Cisco-Qualcomm-Nokia dynasty?

you can’t beat growth stocks when it comes to investing!

…the embedded messaging is “be scared, be very scared, be scared shitless”…and…”no need to think for yourself, just do what your told cause “we” got you covered”…until your covered with dirt on “the edge of eternity”.

Craaz – you get worse – it was 3498288 of the last 2.99. The sky falls tomorrow!

for some people, evidently, the sky is continually falling, which challenges the notion of space & time, but when the sky is falling, there’s no time for complexity!

We’ll take a bag of exotic matter along in our exit strategy and keep the worm-hole open with negative mass.

I do realize that Serious Economists would call these people I’m talking about “Quacks”. But that kind of word isn’t the result of zoological analysis, it’s the result of psychological projection. bowahahahahahaha

The ‘secular stagnation’ crowd would no doubt be happy to see the Fed freed from any responsibility for its bubblicious actions. ‘Policymakers’ are left to clean up the mess.

There’s only a little data in the charts, but they’re pretty funny in the way they show the forecasters predicting the past, only with a moderating factor and a time lag. So they predicted 0 of 13, then 0 of 49, and then started to clue in and predicted 8 of 7 and 4 of 1. That last 15 of 2 must be an outlier that needs more study. Catastrophe theory and fractal math articulate some ideas that could be used to explain how effective inputs to a process can be so small as to be lost in the noise and unmeasurable. Things as abrupt as turning points are left undecidable. Given that, models with windows so the users could look out at the real world once in a while ought to be very popular.

Why am I reminded of the Russian dash-cam video where the dudes drove their car into a river? And then sat there assessing the situation? “Hey, it’s floating.”

Hmmm. Got that wrong, didn’t I? 1 of 4, and 2 of 15. I could still maybe defend my point. Kind of looks like an under-damped machine controller. A prediction too high means the next prediction will be too low, and vice versa. And look how for the March 14 FOMC projection they seem to have noticed something.

You should re-title this “The Frail Elderly as a Source of Profit.”