Philip Pilkington is a London-based economist and member of the Political Economy Research Group at Kingston University. Originally published at his website, Fixing the Economists

Yesterday when I published my post on Krugman and the vulgar Keynesians not understanding the meaning to the term ‘liquidity trap’ I came to realise that many readers — both sympathetic and hostile — do not really understand the Keynesian theory of financial markets. I then realised that this was actually quite understandable given that it is not much discussed today (with some notable exceptions such as Jan Kregel and Minskyians like Randall Wray).

Some years ago the financial markets were very much so discussed and understood. Key references in this regard are the works of Keynes himself (particularly the Treatise on Money), GLS Shackle, Roy Harrod’s book Money and Joan Robinson’s essay ‘The Rate of Interest’. There are also some more minor works but I will not here provide a bibliography. (From a purely theoretical point-of-view I have found Shackle’s work the best while from an institutional point-of-view I have found Harrod’s work best).

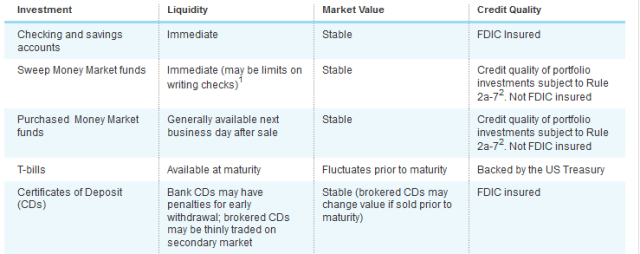

Okay, let’s first start by what we mean by ‘cash’ and ‘bonds’ in Keynesian financial theory. Most people are being led down a wayward path by the likes of vulgar monetary economists like Krugman in this regard (or was he a trade economist? someone remind me…). They seem to think that ‘cash’ is money — deposits, notes, coins, that sort of thing — and ‘bonds’ are government securities. Actually, in financial marketspeak cash includes short-term government securities. It also includes money market funds and other highly liquid investments. There is a nice guide to this at the money manager Charles Schwab’s website here. In this guide the author writes:

What is cash?

Many people think of cash as physical currency—actual bills and coins in circulation. For practical purposes, however, the term “cash” also includes traditional bank deposits, such as checking and savings accounts, where you generally have access to your funds on demand and without risk of losing any principal (up to FDIC limits).

In an investment context, however, the definition of cash expands to other types of cash investments, including short-term, relatively safe investment vehicles such as money market funds, US Treasury bills (T-bills), corporate commercial paper and other short-term securities.

For the purposes of financial macroeconomics I think that we would be best to exclude corporate commercial paper. This is very short-term debt issued by corporations.* Although highly liquid, it nevertheless displays many dynamics associated with what should properly be called ‘bonds’. I would also say that, following the Modern Monetary Theorists (MMTers), we should probably be clear that government securities should only be treated as cash proper if they are denominated in the currency of issuance. (For practical purposes we can modify this when needed).

What about stocks? Stocks are unusual in that they do not yield a rate of interest. Yes, they throw off dividends but this is not the same thing. The rate of interest on bonds is inversely related to the price of the same bonds. When the price rises, the rate of interest falls. When the price falls, the rate of interest rises. On stocks, however, this relationship is by no means clear. Dividends are a completely different beast. Nevertheless, we can count stocks as ‘bonds’ to a large extent if we remember that they do not have the same interest rate dynamics. Stocks are generally expected to rally when the price of actual bonds is high and their interest rates low.

Now this might seem rather odd because we all know how central banks control the interest rate, right? When the central banks want to lower the interest rate they buy up government securities, while when they want to raise the rate of interest they sell government securities and drain reserves. But if government securities are counted as ‘cash’ this really makes no difference. What the central bank is trying to do is to use cash and cash substitutes (government securities) to affect the interest rates in other markets.

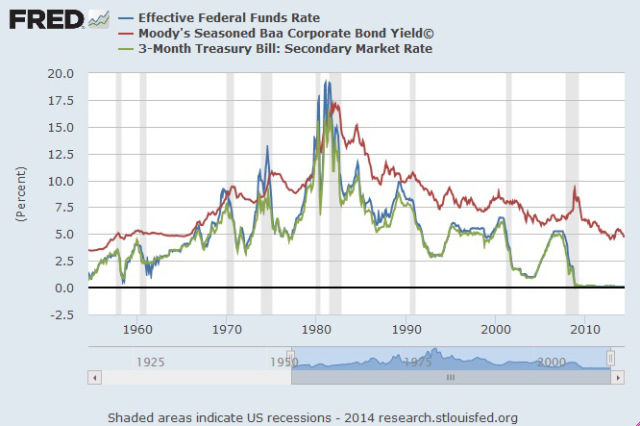

The primary goal of, say, lowering the interest rate is to allow companies to borrow more cheaply. Here is a nice graph showing some interest rates to get a feel for what is going on in the financial markets. We will examine this in more granular detail later.

As we can see, the three-month Treasury bill rate tracks the overnight rate set by the Fed. This is because these are basically cash substitutes. The Corporate Baa Bond Yield, on the other hand — and this is only one of many interest rates I could have chosen — does track the other two to some extent but not completely. Although it generally gravitates toward the overnight rate it does display some independent dynamics of its own.

The gap between the yield on bonds and the ‘cash’ interest rate — to deploy our terminology — is a measure of what Keynes called ‘liquidity preference’. It reflects the market’s taste for low yield ‘cash’ over higher yield ‘bonds’. Let us be clear: in a functioning market there will always be a spread here to reflect relative risk. But, as we shall see, this spread is not fully under the control of the monetary authorities at all times and the amount by which it fluctuates day-to-day and month-to-month is reflective of liquidity preference. Schwab provides us with a nice table telling their customers how to hold this ‘cash’ liquidity.

Very broadly speaking we can say, in Keynesian terms, that checking, saving (and deposit) accounts are used for what Keynes called the ‘transactions motive’. While all the others are used for what he called the ‘precautionary motive’ and the ‘speculative motive’.

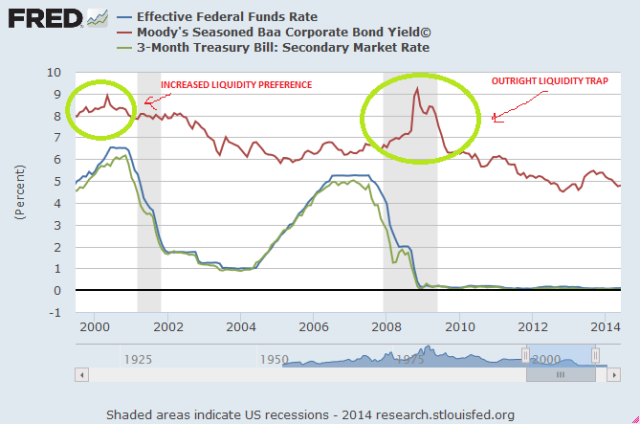

Let us zoom here on a recent period to get a better idea of what is going on.

Here I have marked two recent periods where we see financial markets clearly responding to increased perceived risk. Looking at the time series we see that the Baa Corporate Bond Yield follows the overnight rate quite smoothly. But just prior to the 2001 recession while there was turmoil in the stock markets we see a clear, small spike that is not in keeping with the general smooth movement. This spike accounts for a jump in interest rates on Baa bonds of nearly 0.5%. This may not seem all that significant but in the land of the financial markets it is a very significant event and is indicative of heightened liquidity preference.

The second period I have marked is much more extreme. Here the Fed was rapidly lowering interest rates. Markets were anticipating this lowering too. Yet the Baa bond yield spiked by two full percentage points. This is a liquidity trap proper. The market were roiled by the turmoil that was taking place after 2008 and they all rushed for cash even though the interest rate on this cash was falling. By 2010 the liquidity trap had subsided. This was mainly in response to the markets coming to believe that the bailouts were convincingly going to fix the financial system. TARP did more to ease the liquidity trap, I would argue, than QE did.

Well, that’s all for today class. Use this knowledge to go out and attack the vulgar Keynesians that are clogging up the general discourse with poorly defined terms and nonsense. Today we do not face a liquidity trap. Rather we face a situation in which investment is not responding to low interest rates. That is what vulgar ISLMist Keynesians call an ‘investment trap’ and it takes place when the IS-curve on the ISLM diagram is vertical. While I do not buy into this notion it is far closer to where we are today than being in a liquidity trap. If one must worship at the temple of ISLM at least get it right, for God’s sake!

___

* Yves here. I agree with Pilkington in that corporate commercial paper is “placed”. It is sold to investors and held to maturity, and is rarely resold. Hence it actually is not all that liquid in practice (as in if you were selling CP you had purchased, which is typically not resold, it would be a clear sign that you were desperate and dealers would gouge you).

When the central banks want to lower the interest rate they buy up government securities…

This simply does not apply in the eurozone, where the ECB – unlike the Fed – does not as a rule buy or sell government securities on the secondary markets.

Of course, the ECB still controls the interest rate by providing (or withdrawing) reserves to the commercial banks, via advances.

This apparently minor difference of procedure between the Fed and the ECB has profound implications for the “risk-free” nature of government debt, however.

If the ECB had imitated the practices of the Fed since the inception of the euro, we’d likely never have witnessed a “sovereign debt” crisis developing in the eurozone. Government debt would have been automatically supported by the ECB, rendering a speculative attack against it a virtual impossibility.

‘That is what vulgar ISLMist Keynesians call an ‘investment trap.’

Then the ale-crippled lot rub it in by crowing ‘algo akbar’ in the quadrangle at 2 am, when decent people are trying to sleep.

Cash is king!

Vulture Capitalist’s are waiting for the bottom to “really” fall out. The consumer, the Golden Goose of capitalism, the provider of All revenue for everyone is approaching the end of his rope, and is still under assault.

Any arm chair analyst can see the consumer is also waiting for the “Real” shoe to drop”! The evidence is everywhere.

Look around, governments are only making matters worse!

It is just a matter of time!

Thank you for this post. The final chart shown is particularly enlightening in that it reflects the mortality of the economy and the failed ongoing efforts at its resurrection through the Fed’s zero interest rate policy, which is now entering its seventh year of duration. The continuing spread between the interest yield on seasoned Baa-rated corporate bonds and the negative real rate of interest on 90-day US Treasury bills belies the market’s assessment of systemic risk vs. that of the Fed.

Clearly the Fed and other policy makers continue to believe that low interest rates drive borrowing and the Velocity of money, despite all the evidence to the contrary. Either that, or it’s all about inflating prices of financial assets through financial market manipulation, and concentration of wealth and political power in the hands of a few so called “wealth (destroyers) creators”.

See this chart at the St. Louis Fed.

WHOA…!!!

well, I’m not sure how to make a shorter link.

So, I tried to compare the all the data available between the 10 year US treasury and the “Baa”

Sometimes some people assert something is odd or unusual and if you look at all the data, it is really pretty typical. It seems to me 2000 till now is not “usual”

what strikes me is that the vast majority of the time the Baa and 10 year track pretty closely – indeed, if you didn’t get a shorter time frame, you might not see when the two interest rates diverged at all. (are there any instances in the last 40 years where the 10 year and the Baa diverged as much as they did in 2008????)

So just eyeballing it, it looks like the difference was about 6.5% give or take a half percent?

Gee, that really doesn’t strike me as all that much….because, look, in the past interest rates were much higher…yet people were working. Why in 2008 was such a big deal, and say not between 1990 and 2000 more or less????

This (the Baa spike) is what CAUSED the whole economy to collapse, or is this the AFTER EFFECT of the collapse?

It almost seems like a chicken and egg kinda thing. And its funny (no its not) – the relationship between 10 year treasury and Baa seems to have gone back to “normal” pretty fast….but not the economy. Kinda like once you break the egg, you can’t really fix it???

So does this prove that the FED’s philosophy that it is better to FIX bubbles rather than PREVENT bubbles is all wet?????

And by the way, THANK YOU VERY MUCH FOR CONTINUING TO ELUCIDATE ON THIS IMPORTANT TOPIC!!!!!!!

Use the HTML A tag for the link instead of pasting in the URL. (I tinkered with your comment to include it.)

I was under the impression that people read Krugman for entertainment value.