Yves here. Das gives a high-level overview of what has happened with shadow banking since the financial crisis. As he explains below, despite regulatory pretenses otherwise, it is bigger and likely badder than before. And unlike the runup to the crisis, the Chinese are all in too (see “On a Relative Scale, There’s a Strong Case that Financialization Is Worse in the PRC than the US” and China’s Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs): Ponzi Finance on Steroids for more detail).

By Satyajit Das, a former banker and author of numerous technical works on derivatives and several general titles: Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives (2006 and 2010), Extreme Money: The Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk (2011) and A Banquet of Consequence – Reloaded (2016 and 2021). His latest book is on ecotourism – Wild Quests: Journeys into Ecotourism and the Future for Animals (2024). This is an expanded version of a piece first published on 28 November 2025 in the New Indian Express print edition.

In the 2008 crash, unregulated financial institutions (structured investment vehicles, asset backed commercial paper issuers, securitisation structures, money market and hedge funds) contributed to financial instability. In the aftermath, regulators promised to control ‘shadow banks’ (they prefer the less pejorative ‘market-based finance’ or ‘non-bank financial institutions). But it didn’t happen.

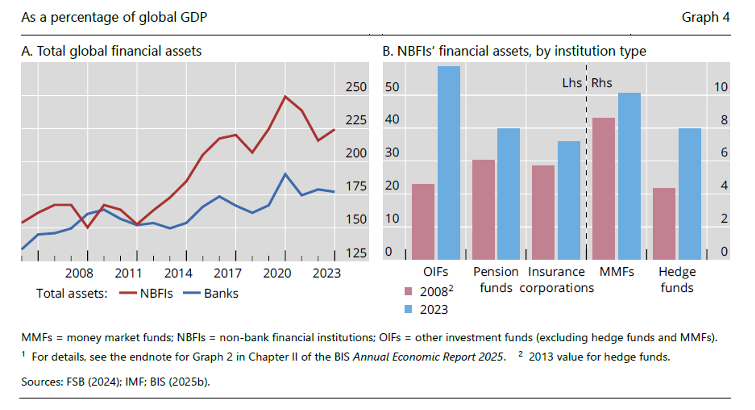

Shadow banks’ share of global financial assets has, in fact, increased since 2008 (see graph below). The value of assets held by insurers, private credit providers, hedge funds and other non-bank financial groups totalled around $257 trillion, growing ate 9.4 percent in 2024. In contrast, banks’ assets rose 4.7 percent to just over $191tn in 2024.

As of 2024, shadow banks total financial assets were 225 percent of global GDP up from 150 percent in 2008. In comparison bank assets, which have grown more slowly are 175 percent. Since 2008, hedge funds have doubled to 8 percent of GDP.

While some structures have declined or disappeared, others have prospered and new ones appeared. Today, the shadow banking complex is dominated by asset managers, such as insurance companies, pension funds, non-bank finance companies and collective investment vehicles (funds, investment companies or partnerships, hedge funds) who invest client money in public and private equity, debt or hybrid securities. Other examples include securitisation vehicles which repackage existing obligations into new securities with different characteristics and various quantitative or multi-strategy trading firms. Other types include specialised fintech firms, microloan organizations, trade financiers include receivables lenders, asset-based lenders (providing leasing, secured loans or receivable finance), payday lenders as well as pawn shops and loan sharks. The phenomenon is global. For example, China has a particularly wide range of shadow banks providing wealth management products, trust loans, entrusted loans, and undiscounted bank acceptance bills.

There are commonalities. All these disparate operations intermediate capital flows between investors (retail, high-net worth individuals, family offices, institutions and sovereign investment vehicles) and businesses. They trade in financial markets using a variety of strategies to profit from buying and selling financial instruments. Most importantly, there is limited regulation relative to that applicable to banks because they theoretically do not take deposits from the public and are not part of the payments system.

Current regulatory concerns about the sector are disingenuous as policymakers’ actions underlie their growing role. Stricter bank regulations, such as the Basle 3 accord agreed after 2008, restricts or raised the cost of certain types of lending especially to SMEs, real estate and projects. This allowed shadow banks to expand to meet credit needs. The prolonged period of low rates between 2008 and 2021 simultaneously encouraged investors to seek better returns in an ever-mutating investment universe. In Asia, non-performing loans of banks made it difficult for them to meet loan demand. Differences in capital, leverage and liquidity requirements drove regulatory arbitrage.

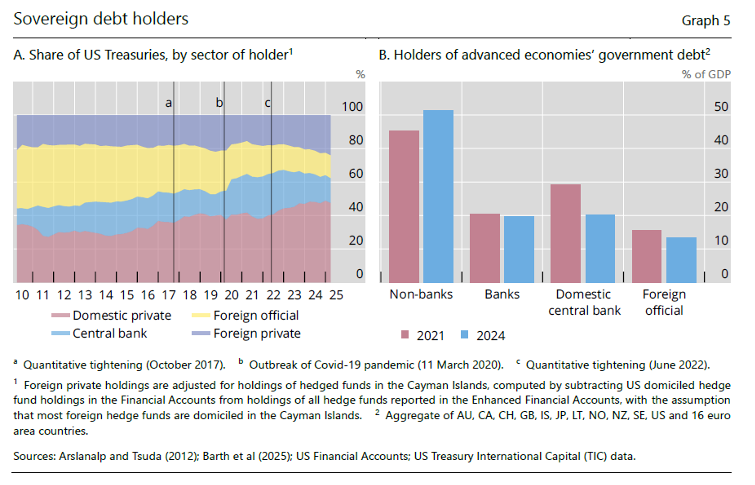

The effects of policy are subtle. Securitisation thrives, in part, because the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank hold 16, 53, around 27, and over 30 percent of outstanding government debt reducing their availability. Highly rated securitised debt meets demand for safe assets and collateral for secured loans.

Interestingly, regulated banks have benefitted from the growth of the shadow banks. They have refocused their business models on the ‘moving’ rather than the ‘storage business’. Banks can now ‘sweat their capital’ more effectively increasing return on shareholder funds by underwriting and distributing loans assets to funds and insurers. For central banks, this increases the velocity of money within the economy.

Circumventing limitations on proprietary position taking, many banks now set up former star inhouse traders in external hedge funds. The primary benefit is income from trading financial instruments with the now off-balance sheet operation and supplying services such as clearing and custody. Banks also provide significant leverage to these vehicles in the form of loans secured by assets or unfunded derivative structures. The substantial profits from prime broking (the terms for these services) testify to the opportunity.

Banks sometimes receive returns on their investments in these funds. Their wealth management or private banking units can offer investments in, or products structured by these external entities.

Shadow banks have profoundly altered the financial system and pose poorly understood risks. They allow difficult to measure increases in debt levels which can exacerbate price bubbles across multiple asset classes.

The higher returns offered to investors suggest that shadow banks take greater risks, unless some secret alchemical process allows circumvention of the normal financial logic. With bank lending concentrated on more secure borrowers, non-banks may be extending credit to lower rated debtors or against riskier assets. Shadow banks frequently enhance yield using leverage at levels higher than that by regulated institutions. The layering of leverage also increases risk across the financial system. There is also heavy reliance on the flawed system of collateral to support credit risk. All this creates potential problems in the event of an economic or financial downturn.

The difficulties are exacerbated by the lack of permanent loss absorbing capital because many shadow banks are funds which pass-through investors’ money. There are concerns around liquidity and redemption risks. To maintain returns, most shadow banks must remain fully invested leaving limited cash buffers. Given significant asset-liability maturity mismatches and holdings of illiquid assets which offer higher yield, unexpected large investor withdrawals can lead to sudden pressures to raise cash. In the case of some institutions, like pension funds and insurance companies, lower returns, losses and inability to access cash may affect their ability to meet contracted liabilities.

There are significant connections between regulated entities and their shadow counterparts. US banks alone have outstanding loans to private credit providers of $300 billion, constituting over a significant portion of all loans. In addition to loans to private credit providers, there is a further $285 billion in credit to private equity funds as of June, and $340 billion in unutilized commitments available to these borrowers. Banks have also provided significant levels of financing to leveraged investors such as hedge funds with prime brokerage loans now around $3 trillion. The total exposure of US and European banks to non-bank financial institutions is estimated at $4.5 trillion.

The primary driver is differential capital treatment. Normal bank loans, other than residential mortgages, are typically 100 percent risk weighted. In contrast, loans to shadow banks may have risk weights as low as 20 percent, effectively reducing capital required to be held against the exposure. This reflects collateral or financial engineering where structures such as securitisation or credit risk transfer mechanisms are used to allow banks to take senior exposure to a pool of assets with other absorbing some initial losses. This makes lending to shadow banks less capital-intensive boosting returns.

Instead of addressing the underlying problems, policymakers have sought to shift risk from regulated deposit-taking institutions to non-banks. They have chosen to believe that problems in the shadow banking sector can be isolated and prevented from infecting banks thus avoiding unpopular interventions and bailouts using public funds. The failures of Greensill Capital and Archegos which were factors in the demise of Credit Suisse demonstrate a different reality. Risks are compounded by the opacity and complexity of these entities.

The most draconian regulatory response would be to strictly quarantine shadow banks. Regulated entities’ dealings with them would be covered with 100 percent cash collateral to minimise exposure. Rigorously enforced prohibitions on bailouts would minimise moral hazard.

A less onerous approach would be oversight and regulation based around function rather than legal form. It would allow greater nuance and flexibility in dealing with differences between entities, their activities and risk profiles. Based on the type of activity, minimum capital requirements, maximum leverage and maintenance of enough liquidity to meet potential redemptions would be mandated. Reliance on short-term funding would be constrained. Vetted sponsors would need to meet prescribed standards of capital, skill and governance. Bank exposures to non-bank institutions, either lending or other dealings, would be controlled. Appropriate protection and disclosure would be instituted.

But the fear of a large contraction of credit availability as well the lobbying strength of the financial sector means any meaningful regulation is unlikely. An increasing factor is that shadow banks are significant holders of government debt(see graph below). Since 2021, the sector’s holdings of advanced economies’ debt have increased to above 50 percent of GDP. In comparison, bank and central bank holdings are less than 20 percent. Hedge fund sovereign debt exposures have more than doubled to about $7 trillion funded in part by repo borrowing that have nearly tripled to surpass $3 trillion.

This means there is a distinct lack of appetite for measures to regulate shadow banks as that would require dealing with debt levels or changing a borrowing driven economic model.

In the next financial crisis, shadow banks will again exaggerate asset price falls, increase volatility, and be a source of financial instability.

© Satyajit Das 2025 All Rights Reserved

It’s a bit disheartening to contemplate the amount of human effort that goes into this “industry”, and what that might accomplish if it were directed towards solving real-world problems. I think that has to be regarded as a form of market failure.

It is a government failure as well. Tax policies on hedge funds and investments, and the creation of the 401k industry that is constantly chasing “delta”, are a large reason why this has happened.

It’s finance as comedy, tragedy, and farce – all at once.

More like a Mafia owned casino dressed up as a legitimate financial operation. Win some, lose some.

Bracing commentary.

257 trillion is a big number.

So if everything is securitised or cross securitised by financial engineered products, how many layers down is the actual collateral and just how leveraged is it? In this financial perpetual motion machine is money still a safe store of value? No wonder houses cost so much. No wonder gold is going parabolic.

“as well the lobbying strength of the financial sector means any meaningful regulation is unlikely”

That’s the core of all the problems in the U.S.. The democrats and republicans will not allow any change to the status quo.

The democrats and republicans are the tag teams of corruption.

The game is to earmark all surplus to FIRE, is that not so.

At the risk of seeming to toot my own horn – I’m actually tooting Lewis Carroll’s horn – the following letter of mine was printed in the Financial Times nine years ago:

Sir, Wolfgang Münchau says “we should start making a distinction between the financial sector’s interests and the economy at large” (“Reform the economic system now or the populists will do it”, December 19, 2016). An author writing in England foresaw this situation over a century ago. I refer not to Karl Marx, but Lewis Carroll. Although Carroll’s 1889 novel Sylvie and Bruno earned its obscurity, there is a gem in it – “The Mad Gardener’s Song”. In one verse Carroll foresaw the metastasis of the financial sector from its proper role, as a facilitator of business activity, to its current position in which it is eating everyone’s lunch:

He thought he saw a Banker’s Clerk

Descending from the bus:

He looked again, and found it was

A Hippopotamus:

‘If this should stay to dine,’ he said,

‘There won’t be much for us!’

If you too aren’t leveraged to the hilt like Archegos’ Bill, are you truly living life? 🥲

I make a modest living trading volatility, so can’t complain! 🥹