By Jérémie Cohen-Setton, a PhD candidate in Economics at U.C. Berkeley and a summer associate intern at Goldman Sachs Global Economic Research. Originally published at Bruegel.

What’s at stake: An intriguing paradox of our age is that the global economy is becoming increasingly local, with super-productive cities driving innovation and growth nationwide. This has generated a discussion as to whether local land use policies, which restrict the housing supply in high productive metro-areas, should be constrained by central governments to limit their negative externalities on overall growth.

Local economies in the age of globalization

Enrico Moretti writes that the growing divergence between cities with a well-educated labor force and innovative employers and the rest of world points to one of the most intriguing paradoxes of our age: our global economy is becoming increasingly local. At the same time that goods and information travel at faster and faster speeds to all corners of the globe, we are witnessing an inverse gravitational pull toward certain key urban centers. We live in a world where economic success depends more than ever on location. Despite all the hype about exploding connectivity and the death of distance, economic research shows that cities are not just a collection of individuals but are complex, interrelated environments that foster the generation of new ideas and new ways of doing business.

Enrico Moretti writes that, historically, there have always been prosperous communities and struggling communities. But the difference was small until the 1980’s. The sheer size of the geographical differences within a country is now staggering, often exceeding the differences between countries. The mounting economic divide between American communities – arguably one of the most important developments in the history of the United States of the past half a century – is not an accident, but reflects a structural change in the American economy. Sixty years ago, the best predictor of a community’s economic success was physical capital. With the shift from traditional manufacturing to innovation and knowledge, the best predictor of a community’s economic success is human capital.

Ejaz Ghani, William Kerr and Ishani Tewari explain that the debate on whether cities grow through specialization or diversification dates back to Alfred Marshall and Jane Jacobs. Marshall (1890) established the field of agglomeration and the study of clusters by noting the many ways in which similar firms from the same industry can benefit from locating together. Jacobs (1969), on the other hand, pushed back against these perspectives – she emphasized how knowledge flows across industries, and that industrial variety and diversity are conducive to growth.

Big cities in the crisis

Richard Florida writes that in the years since the economic crisis, powerhouse metros like San Francisco, New York, and Washington, D.C., have continued to grow in importance. In 2012, the top ten largest metropolitan economies produced more than a third of the country’s total economic output.

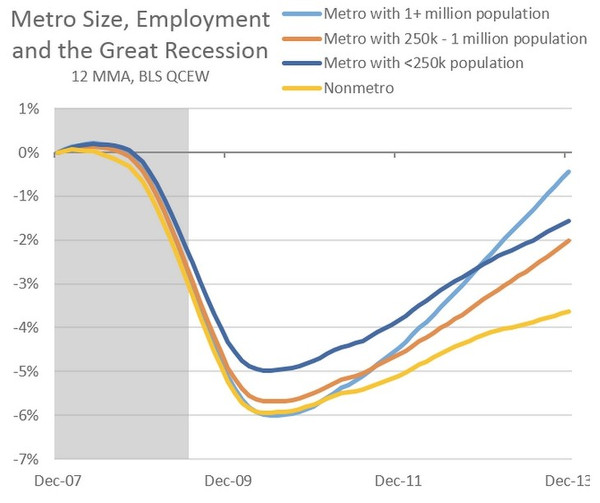

Josh Lehner writes that the largest metros (the 51 largest have a population of 1 million or more) have seen the strongest gains in recovery. The second set of metros have seen some acceleration and the nonmetro (rural) counties have seen deceleration over the past year. It is also interesting to note that only the largest cities have seen growth rates return to pre-recession levels, while the others lag. This is at least partly due to the nature of the Great Recession in which housing and government have been large weights on the recovery. These jobs also play a disproportionately large role in many medium, smaller and rural economies than in big cities.

Source: Oregon Office of Economic Analysis

Dealing with the nationwide externalities of local regulations on land use

Wonkblog reports that for Enrico Moretti we should care about how San Francisco and big cities like it restrict new housing because the economic repercussions of such local decisions stretch nationwide. These super-productive cities have been among the least likely to add new housing since 1990. By preventing more workers who would like to live in the city from moving in, big cities are holding back the U.S. economy from being as productive as it could be. Yet, despite these negative national externalities, land-use policy has always been a local issue.

Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti write that one possible way to minimize this negative externality would be for the federal government to constraint U.S. municipalities’ ability to set land use regulations. Currently, municipalities set land use regulations in almost complete autonomy, since the effect of such regulations have long been perceived as predominately localized. But if such policies have meaningful nationwide effects, then the adoption of federal standard intended to limit negative externalities may be in the aggregate interest.

Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti write that a possible solution is the development of forms of public transportation that link local labor markets characterized by high productivity and high nominal wages to local labor markets characterized by low nominal wages. Enrico Moretti writes that California high-speed rail has always been thought of as a fast way to move people from Los Angeles to San Francisco, as competing with the plane. But it might be that actually its most meaningful economic impact would be as a way to allow people in Central Valley low-wage cities to commute to the Bay Arean

Inequality and big cities

Kristian Behrens and Frédéric Robert-Nicoud write that inequality is especially strong in large cities. Large cities are more unequal than the nations that host them. For example, income inequality in the New York Metro Area (MSA) is considerably higher than the US average and similar to that of Rwanda or Costa Rica. Large cities are also more unequal than smaller towns. While larger cities increase the income of everyone, the top 5% benefit substantially more than the bottom quintile.

High rise apartments in the Sunset or Noe Valley? Dream on!

Yves, before I dive in to the post, I want to talk about what I see here in Michigan with the so called “growth” of our cities. First, everyone knows or has heard of white flight. That was the result of the 60s civil change and the riots that broke out (there are a lot of theories) and large quantities of white ppl moving out of downtown Detroit to the surrounding suburbs and leaving the inner city to die. But that’s my major complaint. In our other cities flint, Lansing, grand rapids, the surrounding communities have seen huge development and growth while the central part of the city is left to grow old and die. Yet, this is not true growth. What we are getting is companies building brand new facilities on undeveloped land while they shut down their downtown operations and leave the old building to be dealt with by the city. This building becomes an eyesore, becomes used by crime, and then the surrounding businesses leave to join the new building. It’s not growth; it’s a transfer of wealth from one location to another. In Lansing, there are hundreds of acres of unused pavement parking lots from where GM tore down old buildings but did not rebuild. They rebuilt on an undeveloped piece of farmland 8 miles away. Some of the reasons I think businesses would do these things are environmental (regulations that make the cleanup of the site costly, but not expensive), financial related (GM maintains this land on their books as an asset while gaining more assets), the rebuilding costs (an undeveloped piece of land is easy to design and engineer. Reorganizing an existing piece of land may cost thousands more in architect fees and such), and of course “the new factor”.

Right, Ep3. It’s not growth, it’s graft.

I like this format a lot, and I think this a a great compilation of important issues. I hope to have the chance to explore each of these posts in depth. Thanks Lambert.

Since the thoughtless, greedy elites have set up an amoral supranational corporate state, over the people and themselves, which gives special, open ended rights to corporations over nations, the people could and should, I suppose the natural people now can only avoid enslavement by joining up, to set up a supranational structure (of, by and for the natural, not corporate people) to regulate THEM. That way, any harmonization of regulations which occurs would be by necessity up and not down. (another bait and switch, they claimed at the beginning their goal was to harmonize upwards but it has turned into downwards– which is a form of taxation (of the people by increasingly parasitic corporations) without representation. )

For examples, look at the race to the bottom video.

‘That one possible way to minimize this negative externality would be for the federal government to constrain U.S. municipalities’ ability to set land use regulations.’

More centralized control … why has no one thought of this before? /sarc

Ask folks in the west how they like the existing federal control:

More than 50 lawmakers from nine Western states gathered [in April] for a summit in Utah, where an estimated 67 percent of the land is owned by the federal government and which has twice passed provisions seeking to reduce the reach of Washington’s control over that property.

62 percent of Alaska is federally owned, as well as 62 percent of Idaho. More than 81 percent of Nevada is managed by federal authorities; 48 percent of California; 35 percent of New Mexico; 53 percent of Oregon; 29 percent of Washington; and just over 48 percent of Wyoming.

The Center for American Progress, a liberal policy group, wrote that in the last year, “seven Western states — Utah, Arizona, Wyoming, New Mexico, Colorado, Nevada, and Idaho — have passed, introduced, or explored legislation demanding that the federal government turn over millions of acres of federal public lands to the states.”

http://tinyurl.com/mpbacga

By “turn over acres of federal land” you mean turn over the land to corrupt local and state big wigs and the extractive transnational corporations who want to strip mine everything?

Not that the federal government is totally innocent w/r/t this either.

Hi Lambert, I’d be interested to hear more about why you posted this.

The writing strikes me as practically Orwellian, particularly in the way in which such concepts as “innovation” and “growth” are deployed whenever the author gets close to discussing his data in terms of the increasing concentration of wealth. For instance, the graph charting metro size and employment — if I’m correct in assuming that the y axis here represents change in employment it would seem the trend was still negative in Dec 13, yes? while the damage caused by the Recession was worse than in smaller cities. Sure, this could totally be due to the drag caused by “housing” and “government,” and if he’s referring to the impact of federal monetary policy on housing markets in large cities, he’s right in a sense, but I’d be interested in seeing how this data reflects structural changes in these allegedly increasingly “localized” economies. On the contrary, these places could be seen as more diffuse than ever, as wealth from across the globe gains ever greater influence in nearly every tier, from foreign billionaires investing in real estate in Manhattan or Beverly Hills to an influx of college-educated workers from middle-class households who pay inflated rents with family support while working low-wage jobs or unpaid internships. Meanwhile, assuming what one hears is true, many of the job losses you see in 2008 are people who either still struggle to find work or who have been working for considerably less than before, with the attendant effect of ramping up gentrification by creating a strong incentive for these people to sell their homes if they aren’t simply priced out.

I live in LA where there’s a considerable construction boom in at least Downtown and parts of the Valley, and it all appears to be market-rate or luxury housing which starts at something like $1250 for a one-bedroom. I’m a recluse but I’d be very surprised if even the developers of these properties think the demand for that kind of situation is being driven by people getting better jobs, except to the extent that rent is too high for them to save towards the 20% down payment requisite for a mortgage. In any case rent control laws are fairly strong here, at least for multi-unit structures built before ’77, so in some of the older areas of the city the impact of gentrification is limited at least compared to NY or SF.

Anyway, pretty wild to look at this whole situation and conclude that the solution is getting the federal government to override municipalities’ land use regulations, particularly since this argument seems to implicitly acknowledge that growth trends in large cities have very little to do with “localization” in the sense of dynamic, concentrated economies that generate jobs and wage growth, and more to do with a concentration of capital that works in favor of nationally and globally dispersed interests with a greater or lesser degree of access to wealth.

To elicit long, thoughtful comments; as well, the article falls under the heading of

class warfareincome inequality generally. I haven’t seen a cities perspective on this, however. And the chart certainly feels true, even in my own state.Jared, I agree with you regarding this post. What innovation is this guy talking about? Does he mean innovative ways to spend government money in D.C. or new finance derivatives in New York, or the iWatch? If these cities where life is sweet, where our wealthy aggregate to enjoy their good life, intend to have a few folks about to serve the wealthy their food, pick up their trash, roust the low lifes, sell them cool things … they must provide low cost housing and better mass transit — and yes they all have mass transit already at high cost and providing far from ubiquitous service. As for having the federal government step into the mix, that might work if the federal government still worked for us. Even at a time when we’re told things were better, national elites in the worked with elites in the states, and cities to turn urban renewal into a scheme to clear out the riff raff and line the already overflowing pockets of the local, state, and national elites, their pockets, with profits from the resulting improvements to city centers, the highest best uses of property.[ref. “Who Really Rules? New Haven and Community Power Reexamined”, G. William Domhoff] A program running entirely from the federal level — I suppose the national elites could cut out the share they had to leave to local and state players the way Urban Renewal was run.

Lambert, this post is a farce…right? That capital goes where it is most cost effective to distribute and job seekers follow is not rocket science.

In a world where it is considered that local control of finite resources is the most effective and efficient use, someone using economic metrics to claim that “growth” occurs where capital is spent is a charlatan.

Carving up American city neighborhoods along race and ethnicity is an old American pastime. Kinda like a tradition. In so doing city planners sowed the seeds of deep rooted inequality which manifests itself to this day across the broader population. It’s policy.

Throw in an emphasis on “ownership” of very low density single family housing as the only acceptable option (and heavily subsidized in a variety of ways). Plus….if one has a mortgage, one cannot be very “radical” politically, socially, or economically, can one. One is stuck in the system.

Kill off manufacturing leaving only rent seeking industries and then marvel at the importance of cities. Wow!

As per Ralph Gomory, this cannot continue.

So, on a website where many people continually extol the idea that organizing locally can be a partial antidote to the corruption of the federal government we’re discussing the merits of giving developers and their capital backers the power to control the zoning decisions of my local city from D.C? Awesome, I tell you. Awesome. But I guess, if hatred of the automobile in all forms (including the inevitable long range all-electric types) is a driving force in your view of how everyone should live, then packing people into high-rise sardine cans is great for quality of life.

As someone who has spent 13 years and many thousands of dollars working with other local activists to limit and prevent over-development of my small city, I dread the day when developers can join with the hedge funds that hoovered up lots of foreclosed properties to wreak destruction anywhere and everywhere they might be able to make a buck.

And BTW, judging by the capsule summaries, many of these articles treat cities as if they were stand-alone entities rather than as components of massive metropolitan areas. SF restricts development? Gee, really? Why would an already heavily built-up city with lots of hills and narrow streets want to do that? Where do they expect people to live…San Bruno, Santa Clara, San Jose, bedroom communities to the east?

Oh, wait…

Adding: In our local battle we are constantly told that “growth” is the cure for our problems. Only two problems with that:

a) As soon as we rezone and over-build to accommodate current demand, we’ll have to re-re-zone and over-over-build to accommodate future demand that always increases and never ends. (Same basic theory as eternally growing world economic growth, resource limitations be damned.)

b) If growth was the solution, in many areas we would have grown ourselves to utopia long ago.

Sadly, freezing cities which are experiencing population pressures into one paradigm “it was like THIS when I bought in so it can never change” is not very logical, either.

You disparage “sardine cans” Some of us are less fond of “little boxes on cul de sacs” sorted by income class and accessible only by private automobiles.

Who says “Total Economic Productivity” is the number one priority to a community? It is not in the self-interest of people who live in a desirable, productive community to have the hordes moving in just to boost “output.” In fact, the greater the economic “output,” the faster humans go extinct from global warming.

How a city grows may be just as important as growth itself.

I have noticed that with most cities, new subdivisions always takes place outside the city boundary. And while construction takes advantage of city water, sewer, and other services, they still reside outside the tax district. When it comes for the city to annex the new growth and expand the tax base to compensate for the added costs, the area to be annexed always incorporates first in order to avoid taxation by the city. This always cuts off further revenue funds for the parent municipality.

Eventually, the new community itself gets leap fogged and locked in by new incorporated subdivisions, isolating its own tax base and further isolating the parent city.

Over time, the tax base for the inner city suffers. It finds itself with not just providing utilities for itself and many of its own services, but also serves as the foundation for the surrounding communities. But it also has a diminishing tax base from its own residences that increasingly trend poorer, as well as business also starting to flee to the suburbs.

In contrast is Wichita, Kansas which as aggressively annexed surrounding land while it’s still being farmed. Farmers do not mind because it never comes with additional taxes. Even the residence is exempted from city property taxes. But it becomes part of Wichita proper and subject to municipal zoning codes. Only then will the city planer consider extending water, sewer, or street systems for new subdivisions.

The result is that new subdivisions are built already within the city limits, thus there is no annexation battle. And property taxes from the new sub-divisions can be used to offset costs for inner core operations. There is also less of an incentive for business to relocate because doing so doesn’t necessarily mean they move outside the city jurisdiction.

The upshot is that Wichita doesn’t have the budget issues that I have observed with other major cities, despite not having as many residences.

And it dose seem to be Wichita specific because the satellite towns; Maze, Goddard, Derby, and others, are all starting to get leapfrogged themselves. None have yet attempted to annex their surrounding subdivisions, but I suspect that when they try, the areas will incorporate first and we will see a repeat of the same problems. I also wonder if this will impact Wichita in the long run when it runs into these boarders.

One approach for existing larger cities is to change federal statue (current law gives an incorporating district prefrontal status over districts to be annexed) to encourage or even mandate in extreme conditions, the unification of municipal governments. This would allow the intermigration of tax districts, perhaps slow the rate of suburban flight, and give the core district access to stronger tax revenue for shared project and infrastructure maintenance.