Yves here. I’m using this post as an object lesson in what is right and wrong with a lot of economics research to help readers look at research reports and academic studies more critically. That often happens with post VoxEU articles; they have some, or even a lot, of interesting data and analysis, but there’s often some nails-on-the-chalkboard remarks or a bias in how the authors have approached the topic. Readers, needless to say, generally pounce on these shortcomings.

Here, the authors take up a legitimate topic: are surveys on wellbeing asking the right questions? Personally, I find “wellbeing” to be such a nebulous concept that asking members of the public for how they rate their current standing to be a fraught exercise.

The topic is becoming more important as some economists are trying to come up with better measures of prosperity than GDP. For instance, Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen and Jean-Paul Fitoussi have been working with the French government to devise improved metrics for economic performance and social progress.

On the one hand, recognizing that current polls come up short and trying to devise new methods is a laudable goal. On the other, some aspects of how they went about the project are sadly typical. The ones that stood out for me was that they did what amounted to a literature search to come up with a long list of attributes. So far, that seems sensible.

Then from that they went and generated a survey. There are actually two problems with that. The first is that there is a good body of knowledge as to how to design and conduct surveys so at to get valid, repeatable results. My knowledge is about 20 years stale, but I suspect the principles are still generally valid. You do qualitative research first (as in in depth interviews with people who are representative) to generate themes and find out how they use language. This was a step that was likely important here, since the themes and ideas they got were from academics, economists, and philosophers, and their use of language could have varied in subtle but important ways from that of the target population (survey results are VERY sensitive to how questions are phrased). The next step is to “validate” the survey instrument by taking variant of the questions and also stacking the questions in different sequences to see how to eliminate any biases (of course, if you are Rasmussen, you would try to introduce them).

Note that surveys are rarely done well because it is time-consuming and costly to debug them properly. But in this case, I suspect it’s also the result of economists famed lack of interest in learning from other disciplines.

But even allowing for the fact that these researchers didn’t have the budget to undertake this project in a rigorous manner, there’s a glaring error in how they constructed it. The questions are not mutually exclusive. They asked respondents to rate the importance of various aspects of wellbeing. One response was “The overall wellbeing of you and your family.” They also had “Your health” and “The happiness of your family” and “Your mental health and emotional stability.”

The “overall” question is a superset, and the next three I cited are subsets of it. It’s no surprise that the superset scored higher; that’s precisely what you’d expect.

Daniel J. Benjamin, Associate Professor of Economics, Cornell University; Samantha Cunningham, Project specialist, University of Southern California; Ori Heffetz, Associate Professor of Economics, Cornell University; Miles Kimball, Professor of Economics and Survey Research, University of Michigan; and Nichole Szembro. Assistant Professor of Economics, Trinity College. Originally published at VoxEU

GDP has long been used as a measure of a population’s wellbeing, but there is a growing interest among policymakers and researchers to go “Beyond GDP” (Fleurbaey 2009) – to find better measures of a person’s actual lived experience than the value of her income or expenditure.

One idea is to directly ask people about their wellbeing. Recently investigated survey measures of ‘subjective wellbeing’ (SWB) have primarily focused on measuring aspects of SWB such as happiness and life satisfaction. The basic problem faced by single-question SWB measures (such as happiness or life-satisfaction questions) is that they do not manage to capture all the wellbeing aspects that enter into preferences (for recent evidence, see Benjamin et al. 2012 and 2014a). Indeed, a consensus is emerging among researchers that wellbeing is multi-dimensional, and more than one survey question is needed to assess it.

Some governments have begun adding SWB questions to national surveys and expressing intentions to use SWB measures to guide policy. For example, the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) added the following questions to their national Integrated Household Survey:

• Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?

• Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday?

• Overall, how anxious did you feel yesterday?

• Overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?

But it is not clear that these four questions – or for that matter, any small number of questions taken from the academic literature – are sufficient to adequately measure wellbeing.

Going Beyond Happiness and Life Satisfaction

What questions should governments ask instead? How should the responses to these questions be used? In our recent paper “Beyond Happiness and Life Satisfaction: Toward Well-Being Indices Based on Stated Preference” (Benjamin et al. 2014b), we attempt to take on these questions. We propose to go “beyond happiness and life satisfaction” and construct a more comprehensive measure of SWB, an index – with weights based on stated preference – that captures a fuller picture of a person’s wellbeing.

In Benjamin et al. (2014b), we take as a starting point the idea that people have preferences over ‘fundamental aspects’ of wellbeing. The theory is grounded in the economic principle of revealed preference, which holds that a person’s informed choice is the best criterion for judging what increases her welfare. Following that logic, we created a survey that asks a respondent to choose between increases in different wellbeing aspects (so we can learn which option would better improve her welfare). Using her answers, we can estimate the respondent’s relative ‘marginal utilities’ of aspects of wellbeing – meaning how much the respondent values a small increase in each aspect. These relative marginal utilities can then be used as weights to combine the aspects into a wellbeing index for the individual. We find it more attractive to use a person’s stated choice as the sole determinant of the index’s weights, rather than to (paternalistically) rely on the opinions of experts regarding how to weight (i.e. what level of importance to assign) aspects of that person’s wellbeing.

Implementing our approach requires knowing the list of aspects of wellbeing that matter to people – a list that no one really knows. For the time being, we instead construct a long list of all the aspects of life that have been proposed as important components of wellbeing in a sample of major works of psychology, philosophy, and economics (e.g. Maslow 1946, Sen 1985, Ryff 1989, Nussbaum 2000, Alkire 2002, Diener and Seligman 2004, Loewenstein and Ubel 2008, Stiglitz et al. 2009, Graham 2011). To our knowledge, ours is the most comprehensive effort to date to construct such a compilation. Our current list includes 136 aspects. Most are ‘private good’ aspects, or aspects that relate to the individual’s own wellbeing (e.g. ‘your health’), but many are ‘public good’ aspects, or aspects that relate to an entire society’s wellbeing (e.g. ‘equality of opportunity in your nation’).

The drawback of attempting to generate a comprehensive list is that it increases the likelihood of conceptually overlapping aspects (i.e. aspects that describe the same fundamental aspect). We have tested the results we discuss below (i.e. the estimated marginal utilities) to ensure they are not affected by overlap. However, when it comes time to actually construct a wellbeing index by combining these relative marginal utilities, overlap would lead to double counting of some aspects. This is one problem we do not fully resolve in the paper (though we suggest a research strategy for identifying the extent to which the aspects of wellbeing measured by survey questions overlap).

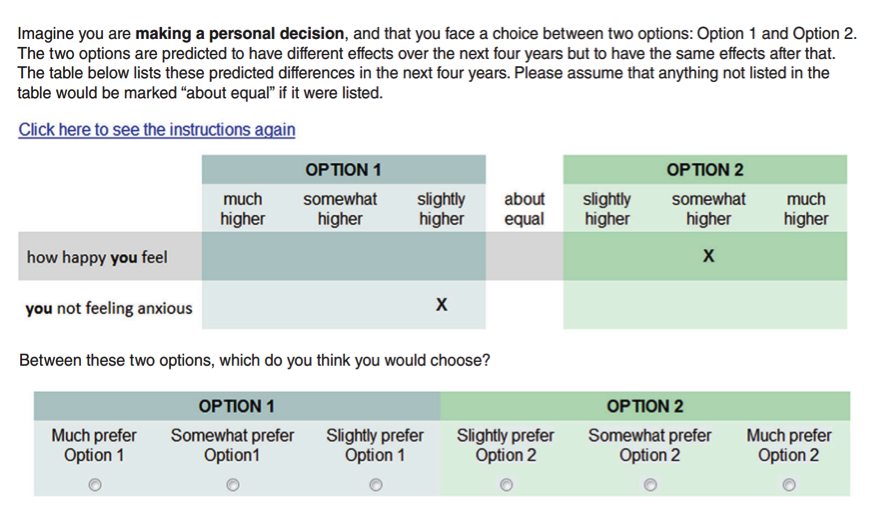

We designed and conducted a stated-preference survey to demonstrate how our framework could be applied in practice, and how wellbeing indices could be constructed using our methodology. A stated-preference survey estimates relative marginal utilities of aspects of wellbeing, to be used as weights, while a SWB survey – like the UK example above – measures levels of these aspects. The survey sample we used was not nationally representative but was demographically diverse and included over 4,600 internet survey respondents. Respondents were asked to choose between two options that differ only on how the aspects in each option changed. For example:

Figure 1. Example survey question

In this example, two aspects are varied: “you not feeling anxious” is “slightly higher” in Option 1, and “how happy you feel” is “somewhat higher” in Option 2. The randomly chosen number of aspects in each scenario was either two, three, four, or six aspects, which were divided between Option 1 and 2.

Each respondent was presented with a sequence of ‘personal-choice’ and ‘policy-vote’ scenarios. Personal-choice scenarios contained only private good aspects, while policy-vote scenarios contained both private and public good aspects. When private good aspects appeared in policy-vote scenarios, the language was changed from “you” to a pronoun that would refer to everyone affected by a policy (e.g. “your health” became “people’s health”).

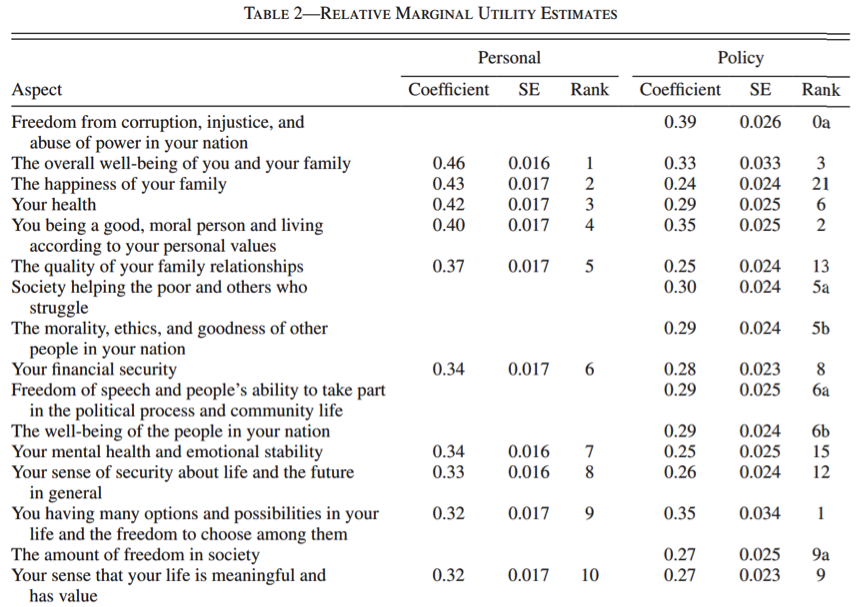

Because each scenario’s aspects and their ratings (i.e. “slightly higher”, “somewhat higher”, or “much higher”) were randomly assigned, we can estimate the relative marginal utilities of the aspects by running a regression in which the respondent’s choice (Option 1 or 2) is the dependent variable and the aspect ratings are independent variables. Aspects were ranked by the size of their coefficient, which is an estimate of their relative marginal utility. Below we reproduce part of Table 2 from Benjamin et al. (2014b), showing the top ten ranked aspects.

Figure 2. Relative marginal utility estimates

Among the aspects used in the personal scenarios, we found that aspects commonly asked about in SWB questions, such as happiness and life satisfaction, were important to wellbeing (i.e. had high coefficients). However, several aspects not commonly asked about were also important, including those involving family (wellbeing, happiness, and relationship quality), health (general and mental), security (financial, about life and future, and physical), values (morality and meaning), and options (freedom of choice and resources). In fact, in the “Personal” panel in Figure 2, none of the top ten aspects are commonly used as SWB measures.

In policy scenarios, we found that aspects that were high-ranking in personal scenarios retained their high rank. In addition, private good aspects related to freedom (freedom to choose, ability to pursue your dreams, being treated with dignity) and avoiding abuse (avoiding deception, avoiding pain, avoiding emotional abuse) ranked higher as policy than as personal aspects. Public good aspects had among the largest coefficients, including freedom from corruption, injustice, and abuse of power, society helping those who struggle, the morality of other people, freedom of speech and of political participation, and the wellbeing of the people in your nation. Respondents seemed to emphasise expanding their choice set in policy decisions.

Concluding Remarks

The kind of survey we ran could be used to estimate relative marginal utilities of a comprehensive list of wellbeing aspects at regular intervals across a large sample. As noted above, we found several aspects to be important in our study that are not commonly included in SWB surveys, such as those related to family, values, and security. The inclusion of these factors in future research is therefore important. However, due to constrained resources, our survey only accomplishes a first-pass demonstration of feasibility. Ideally, a government would design a survey that contains both SWB and stated-preference components – that is, a survey that first asks respondents to choose levels for different aspects and then to choose between different profiles of aspects in order to estimate marginal utilities.

We have taken a step “beyond happiness and life satisfaction” towards a better measure of SWB, but it is only a first step. Work on measuring SWB is still in its infancy and much more needs to be done before reliable measures of national wellbeing can be generated. Accurate national measures of any indicator cannot be developed quickly – after all, it took decades to refine GDP into the national statistic it is today. We hope that our framework will help accelerate research to find better measures of wellbeing, so that policy may be guided not just by what strengthens a person’s economic and financial portfolio, but by what improves the sum total of all the things that matter in life, in accordance with each individual’s own views.

References

See original post for references

Another approach that people interested in thinking about swb might find interesting is the Max-Neef’s work on need satisfaction (summarized/introduced here, for instance).

I’ve run across his work fairly recently, but one of the first advantages of thinking of development (and societal health) in terms of need satisfaction (properly defined; see link) that comes to mind, is that it makes it almost impossible for people to deny the relevance of the findings.

Yeah Sen’s work naturally fits with the ideas of the person obtaining enough of the key items in life to satisfy their needs. I made a post about the poor methodology of the quantitative work in the VOXeu paper but unfortunately it never appeared – probably tagged as spam for some reason :(

Thank you for the link to Max-Neef.

How about using Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and measuring the percent of the population at each level. This would have the advantage of being somewhat objectively measureable.

The influence is clearly there. How I see these MN needs relate to Maslow: subsistence -> basic physical needs, protection -> safety, affection -> love, participation – loosely ties to both love and esteem, identity -> esteem

Maslow posited understanding -> cognitive and creation -> creative needs but they were not part of the hierarchy.

Leisure doesn’t really map, and freedom maybe vaguely to self-actualization.

Whether Maslow hierarchy of needs really was a hierarchy that had to be satisfied in that order even Maslow himself was not 100% on.

As so often in this form of reasoning, this treats ethical considerations as kinds of preferences; as is often pointed out, many people experience them — and they plausibly should be experienced! — not as preferences but as other kinds of commitments and constraints. E. g. they’re not the kind of considerations you trade-off against other sources of utility/forms of well-being.

“Happiness is love. Full stop.”

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/05/thanks-mom/309287/

What I will note, during the holiday season when suicides are at max, is that ‘the happiness of your family’ does not contain a dimension addressing estrangement or distance from that family.

Actually, suicides do not rise during the holidays in the US. Rather, the media take some sort of perverse pleasure in magnifying holiday suicides making it appear to be a rise. December actually has the lowest rate of suicide.

http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/holiday.html

Huh. Now I know, thank you.

Hello,

For me happiness is a product of well being. I view well being as the best utilization of your life for sustainable causes to enhance humankind. Things involved are like knowing people in your neighborhood and constantly engaging in a dialogue. That brings about knowing what is going on the society near you. After that you try to avoid and solve those problems with the help of every one with in the society with minimal help from outside the society. When people around you are happy because of your contributions you get a sense of well being. That eventually leads to happiness.

We in the modern world are way too civilized, too dependent and trust people on the other side of the planet not knowing if there will be a tsunami tonight. This kind of dependencies for meager penny profits defines the risk that we are assuming for less. This risk taking for less and less is associated with societies with tough to make a living concept.

I feel better if I worked for my bank in my village or a farmer in my village rather than have to travel over 3 oceans and 3 continents to work for an international bank whose ceo I hardly happen to know. More than anything I have no idea what good value has my work yielded and where it yielded.

Globalization has its own issues with well being.

What if some important aspects of wellbeing are not measurable nor effable

‘It’s so beautiful I can’t describe it with words.’

‘I am so happy I am speechless.’

I recall all the books I read about heaven, paradise, bliss or enlightenment where the authors never described what it is, with all the details, but just sort of glossed over it.

‘How do we measure it?’

So, we just busy ourselves with what we can measure.

Thus, we advocate measures to prevent or lessen physical violence, but fail to do much with emotional violence. ‘He hit me. 30 days in jail for him.’ ‘She cursed at you, sure. Just take it easy and move on.’ But emotional pain hurts more, or at least as hurtful.

It’s kinda like nobody really wants to put too fine a point on unhappiness. Where are all the surveys asking questions like, What single thing causes you the greatest misery? What image makes you feel nauseous? What sound sets you on edge? What environmental poisons really bum you out? What makes you the most unhappy about your daily exhaustion? What aspect of inequality hurts the most? Do you think it is rational to expect to achieve any of your goals? I mean, it could be a very productive survey if anybody really wanted answers.

It’s been a lot of years, but IIRC the Epicurean idea of happiness was to get rid of all the causes of unhappiness (not actual pleasure-seeking which is the usual idea people have of Epicureanism).

“What single thing causes you the greatest misery? ”

awareness of my own mortality. Ok you need a runner up. then WORK isn’t that far behind!

“What image makes you feel nauseous?”

Obama’s evil smiling visage? I don’t know. I really do hate to see it.

“What sound sets you on edge?”

car honking, any sound when I want silence

“What environmental poisons really bum you out?”

mercury in tuna and arsenic in rice. YOU CAN’T EVEN *EAT* ANYMORE THESE DAYS!! That’s insane.

“What makes you the most unhappy about your daily exhaustion?”

dimly lit offices with no natural light, the fact I have to work so much. Again WORK!

“What aspect of inequality hurts the most?”

The ability of the rich to buy the government and everything that follows from it, the feeling of lack of not just individual but even collective control over how our society is run and even of the future of the planet. The constant competitiveness, the economic and job insecurity, the driving up the prices of rentier items (like housing).

“Do you think it is rational to expect to achieve any of your goals?”

Any? Yes.

Here’s another author on this subject: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/beyond-gdp-9780199767199?cc=us&lang=en&#

Here’s a paper by this guy: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi=10.1257/jel.47.4.1029

I’ve read the paper. It’s interesting to see several views compared and contrasted. In the end, I think this may not be the exactly right question. Maybe we need to think more clearly about what purpose we want the economy to serve. Then we might be able to measure whether it meets that purpose. Certainly a society aimed at funneling money to the filthy rich isn’t viable or valuable. But what exactly is our goal?

For me wellness depends on:

-Health

-Creature comforts

-And the discrepancy between reality and my expectations.

No one seems to be measuring this discrepancy. And our Western society’s value system promotes its growth.