Yves here. This is an important, accessible post that describes something we’ve discussed occasionally: that growth in private borrowings is a type of economic drug. While it appears salutary in the early stages, too much leads to financial instability and crises. This view is presented long-form in Richard Vague’s recent book, The Next Economic Disaster: Why It’s Coming and How to Avoid It, and we featured an excerpt from it.

This post gives a more rigorous look at the same issues and reaches similar dire conclusions.

By Lynn Parramore, Senior Editor at INET. Originally published at INET

Alan Taylor, a professor and Director of the Center for the Evolution of the Global Economy at the University of California, Davis, has conducted, along with Moritz Schularick, ground-breaking research on the history and role of credit, partly funded by the Institute for New Economic Thinking. He finds that today’s advanced economies depend on private sector credit more than anything we have ever seen before. His work and that of his colleagues call into question the assumption that was commonplace before 2008, that private credit flows are primarily forces for stability and predictability in economies.

If current trends continue, Taylor warns, our economic future could be very different from our recent past, when financial crises were relatively rare. Crises could become more commonplace, which will impact every stage of our financial lives, from cradle to retirement. Do we just fasten our seatbelts for a bumpy ride, or is there a way to smooth the path ahead? Taylor discusses his findings and thoughts about how to safeguard the financial system in the interview that follows.

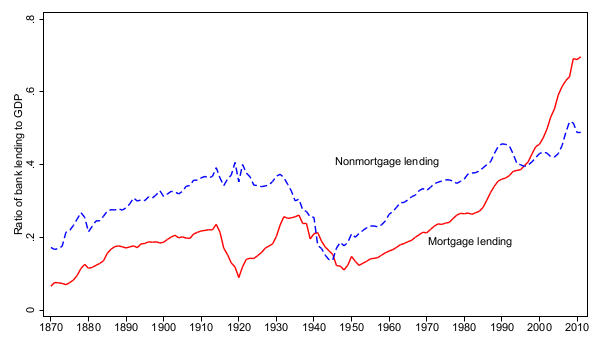

Mortgage (residential and commercial) and non-mortgage lending to the business and household sectors. Average across 17 countries.

Lynn Parramore: Looking back in history at 17 countries, you discovered something interesting about the private sector financial credit market. What did you find?

Alan Taylor: Our project compiled, for the first time, comprehensive aggregate credit data in the form of bank lending in 17 advanced countries since 1870, in addition to some important categories of lending like mortgages.

What we found was quite striking. Up until the 1970s, the ratio of credit to GDP in the advanced economies had been stable over the quite long run. There had been upswings and downswings, to be sure: from 1870 to 1900, some countries were still in early stages of financial sector development, an up trend that tapered off in the early 20th century; then in the 1930s most countries saw credit to GDP fall after the financial crises of the Great Depression, and this continued in WWII. The postwar era began with a return to previously normal levels by the 1960s, but after that credit to GDP ratios continued an unstoppable rise to new heights not seen before, reaching a peak at almost double their pre-WWII levels by 2008.

LP: How is the world of credit different today than in the past?

AT: The first time we plotted credit levels, well, we were almost shocked by our own data. It was a bit like finding the banking sector equivalent of the “hockey stick” chart (a plot of historic temperature that shows the emergence of dramatic uptrend in modern times). It tells us that we live in a different financial world than any of our ancestors.

This basic aggregate measure of gearing or leverage is telling us that today’s advanced economies’ operating systems are more heavily dependent on private sector credit than anything we have ever seen before. Furthermore, this pattern is seen across all the advanced economies, and isn’t just a feature of some special subset (e.g. the Anglo-Saxons). It’s also a little bit of a conservative estimate of the divergent trend, since it excludes the market-based financial flows (e.g., securitized debt) which bypass banks for the most part, and which have become so sizeable in the last 10-20 years.

LP: You’ve mentioned a “perfect storm” brewing around the explosion of credit. What are some of the conditions you have observed?

We have been able to show that this trend matters: in the data, when we observe a sharp run-up in this kind of leverage measure, financial crises have tended to become more likely; and when those crises strike, recessions tend to be worse, and even more painful in the cases where a large run-up in leverage was observed.

These are findings from 200+ recessions over a century or more of experience, and they are some of the most robust pieces of evidence found to date concerning the drivers of financial instability and the fallout that results. Once we look at the current crisis through this lens, it starts to look comprehensible: a bad event, certainly, but not outside historical norms once we take into account the preceding explosion of credit. Under those conditions, it turns out, a deep recession followed by a long sub-par recovery should not be seen as surprising at all. Sadly, nobody had put together this sort of empirical work before the crisis, but now at least we have a better guide going forward.

LP: How do your findings differ from the typical economic textbook story about the role of credit?

AT: I think it’s fair to say that most economic textbooks have had little to say about the role of credit, at least outside the traditional money and banking courses.

Certainly in most macroeconomics courses, both graduate and undergraduate, this topic got little attention before the crisis. However, the classroom approaches are certainly changing nowadays, and that’s a welcome development. It might take a bit of time to filter down into the textbooks, but it will eventually. It’s just very hard to teach a class of students about what has happened in the Global Financial Crisis, how we ended up there and how we got to where we are today, without having some basic, non-trivial understanding of the financial sector, credit, and the banking system. From a purely descriptive standpoint, our efforts to collect historical data establish many important facts that help to frame that discussion, and our statistical analysis sets out some of the key relationships that theories need to explain. But there’s obviously much more to do.

LP: How will the dramatic increase in private sector credit potentially affect our lives as we try to do things like save for retirement?

AT: In the immediate postwar era, financial crises in advanced countries were rare events, and before 1970 did not happen at all. Since then they have occurred more often, and 2008 was the most damaging of them all to date. If we have moved back to a regime of regular financial crises — like the one we had from the 1870s to the 1930s — then our economic future will be very different from our recent past.

Macroeconomic stability will be more elusive and that will affect all of our lives: from the risks many will face in childhood, to the security of employment at working age, to the challenge of accumulating for retirement. More financial instability will introduce more uncertainty all down the line, and that will be a very different world than the one we would have lived in only a couple of decades ago. But that period of calm also tells us that such instability isn’t necessarily a fact of life, and addressing that is likely to be the policy challenge going forward.

LP: Do you think there is a chance that the world might return to something like the pre-1970s historical norms, which would imply tighter credit?

AT: It’s tough to make predictions. We have never in human history seen a run-up in credit of the kind we have just witnessed in advanced economies since 1970, and we have never observed modern finance-capitalist systems operating over a sustained period at this kind of credit-to-GDP leverage ratio. So anything I have to say here is out-of-sample speculation. In fact will credit even tighten at all?

I would guess three outcomes are possible. The first is that we gradually and slowly delever, and advanced economies operate at a credit-to-GDP ratio similar to the 1950s or 1960s, a period when we had strong growth and no financial crises. The puzzle then is how we redirect retirement and other desired saving currently going into credit channels, or at least outside the banking systems. We may end up with a world based more on equity than debt, or more on market debt instruments than bank intermediation; but how and why we get there is a mystery. Absent significant regulatory or tax changes, and a sharp transition could be disruptive.

A second possibility is that we stabilize at current levels of leverage, with some ups and downs, but no further rise in credit to GDP over the long run; firms and households do not lever up further and banks do not expand their balance sheets, but they are persuaded to bolster their capital and liquidity provisions for prudential reasons to mitigate the risks of operating a high leverage system.

The third possibility is that we see more and more leverage, and credit-to-GDP ratios rise once more to even higher levels; eventually the banking systems of all advanced economies reach magnitudes of 500 percent, 1000 percent or more of GDP, so that every economy starts to have financial systems that resemble recent cases like Switzerland, Ireland, Iceland, or Cyprus. That might be a very fragile world to live in.

LP: What measures can policy-makers take to restore balance and sustainability to the credit system? What do you think might be their costs and benefits?

AT: The news here is that much has changed since the crisis. The direct fiscal costs of bailouts, and the even larger indirect fiscal costs of massive recessions (unemployment, low growth, fiscal strains, etc.), have made the status quo unpalatable to governments and the taxpayers behind them. For most, another crisis like 2008 is not acceptable. Operating in this milieu, the central banks, the governments, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and other parts of the macro-financial policy world are now taking a much keener interest in what the pros and cons of different financial regulatory structures and various macroprudential tools (designed to identify and lessen the risks to the financial system) might be.

Echoing many others, for example, Alan Greenspan has noted that the idea that the financial system be left to largely run itself based on enlightened self-interest is a flawed approach. But the alternative isn’t obvious. The benefits of tighter macroprudential controls on credit are, hopefully, fewer costly crises of the kind we just lived through; but a potential trade-off is there, the concern that if we tighten credit too much, we might slow down growth as the price to be paid for diminishing volatility. How to understand that set of choices, and find the best outcome, is a vexing challenge which policymakers and economists must now confront.

As long as we have default swaps larger than global GDP and taxpayer explicit backstops, there’s no reason to not continue levering up, creating more grotesque amounts of debt, driving interest rates to zero. It’s a brave new world.

Well, if only we had “real” negative interest rates, we could borrow more, more, more!!!

And as those debts would simply melt away, we’d all live in a material paradise….

borrowing is income, debt is wealth

OR, as they say, everybody’s debt is somebody’s asset! (funny how that actually didn’t work, and all the “capitalists won’t to exchange their debt freely bought and sold on the efficient “FREE MARKET” for those boring government bonds…)

There’s a book I just read which is pertinent to what you both said, and this article:

Open Secret, by Erin Arvedlund

And I loved the explanation for the LTCM blow up in the 1990s, and James Rickards and his $1 billion CDS!

I thought Steve Keen was working on modeling private sector debt well before the crisis hit? And he looked at historical data including pre-war and post-war credit levels. Why isn’t his work credited?

Taylor is, despite the focus on credit, in the mainstream. Such people do not credit heterodox economists, they approproate their good ideas and move on. Think Krugman.

…’enclosure’ expanding to IP.

Yes this is Keen’s beat. He is always banging on about how public debt is negligible against private, the rate of change of which is the harbinger of a burst bubble, or worse.

Surprised he’s not mentioned.

Actually, there were a fair number of people who had put together this sort of empirical work — I think it’s present in Hyman Minsky. It had just been forgotten by most of the ” mainstream ” economists, because academic economics had turned into a cult. :-(

How to change the track on a runaway train driven by banksters & their minions. without causing a total derailment.

As time passes, perhaps with rose tinted glasses – I remember my late 60’s early 70’s childhood & teenage years with growing affection. Communities built around working class estates & workplaces, plenty of jobs, much more freedom than kids get now, actual leftist political parties, music that was not produced like pot noodles, stay at home Mothers & the lack of health & safety Nazis squeezing the essence out of fun.

Pre-senile nostalgia probably & nothing is or ever was perfect, but I feel very sorry for kids today, who it seems to me are by necessity, being processed like sausages.

Looking forward to the next derailment. I predict the transition between Obama and _______ .

Not a lot of choice in that black line of yours.

“May you live in interesting times.”

I could have written your post. But what I recall with the most affection was the downtime we had. Every second of the day was not filled with something to do or somewhere to be. TV was just as terrible, so there was no point in turning it on, but radio…. wow. Just sitting around listening to the radio or playing records.

So, what happened in the 70’s?

1) the Baby Boom came of age, and the perennial US labor shortage ended.

2) The Middle East exploded and the Oil Embargo to punish the West for supporting Israel was enacted

3) the gold standard was dropped like a hot potato, and inflation due to inadequate taxation roared into life.

4) The Vietnam War was ended due to pressure at home and miserable failure on the battlefield.

I think gross mishandling of the nation’s affairs (due to the total distraction of Watergate) started us down to these pits of Hell. And because of the “leadership” thing, we took the world with us.

But even more significantly, the bankers got restless….

the money system’s final anchoring to anything tangible was severed in 1970.

Paper money has no limits to its production. In reality this is a FIRE money system (not splitting legal hair here) for the non-Fed sector. So naturally this led to multi billionaires in the FIRE sector.

But money (aka someone else’s debt) does require collateral, and even the land based collateral inflation is not enough to feed the greed. So more and more human activities have to be collateralized,eg, education. This is just the nature of the compound interest based money system – as Gisell pointed long ago. And the reason why, to survive, interest rates must fall to zero as the stock of money (principal) explodes. To those who can control interest rates, that is. The Little People will have to pay interest and taxes as usual.

No, it doesn’t.

Thank you, Lambert. The problem here is that Nothing But The Truth confuses “credit” and “money.” It is a common mistake. Credit is something a bank creates when they make a loan. They credit the borrower’s account with a balance equal to the net proceeds of the loan (still not money). This credit of the net proceeds is NOT funded by “money” from some other source. It is created by the creation of the loan (the IOU). Most of what passes for “money” in the 21st Century is “credit” masquerading (and treated like) money. I got in trouble here in the Comments a couple of days ago on similar topics. I’ll let my betters take it from here. ;-)

There are actually three tiers. Currency and bank reserves are high powered money, interchangeable with T-bills, and checks written to pay federal taxes are paid from bank reserves. Bank IOUs, as deposits to your account, require some reserves and currency to be obtained by the bank in exchange for collateral from the FED, to back the deposits , and the deposits are guaranteed by the FDIC up to a given amount. The third tier is represented by IOUs deposited to accounts by non-bank lenders, and neither guaranteed by the FDIC nor necessarily backed by bank reserves. This tier represents shadow bank lending.

With about 7 trillion in deposits and only about 100 billion in required reserve deposits, not much difference between your 2 and 3. Will the FDIC insure against derivative blow ups now that depositors are now assigned a lower priory?

The FDIC insures the deposits in a bank, not derivatives held by the same bank. If the derivatives are not pushed out, it may be more likely the FDIC will have to step in to protect the deposits in case of bank insolvency, if the derivatives blow up. I don’t think it makes a difference, because the banks in question are already insolvent. That is concealed and not readily apparent because of balance sheet sleight of hand, like 2008.

Credit is money because that is how government and the banking sector define it to be and treat it as. It becomes true by definition. Hence much of the problem with the economy as well as the source of peoples confusion.

MMTers can say its not money all they want. It doesn’t change the demonstrable fact that it is – because the law says it is. Where the conversation needs to go is why this is a mistake and how to build alternatives.

Money is not “an emergent property” of modern economics. It is a legal construct set by the state. The question is, what is that legal construct? I am not sure even the government or banks know any more.

What doesn’t – this? “But money (aka someone else’s debt) does require collateral”.

Not literally true – greenbacks wouldn’t – but arguably a fair description of the present system.

Even greenbacks had this as collateral: They could successfully retire the inevitable liability of taxes.

As for number 2: “The Middle East exploded and the Oil Embargo to punish the West for supporting Israel was enacted.”

That has always been the official line. However, there’s reason to believe the major oil companies conspired to manufacture the oil crisis in order to raise the price of oil and reap big profits. Then as now, the U.S and Europe owned most of the major Middle East producing countries, and it’s highly unlikely those client states would have brought about the embargo without the connivance of Western governments.

Paul Scott Davis, for one, has pointed out the glaring holes in the official story.

Even Wiki indicates that not only did Norway, Venezuela and Mexico profit handsomely, but so did the U.S. oil barons:

” In the United States, Texas and Alaska, as well as some other oil-producing areas, experienced major economic booms due to soaring oil prices even as most of the rest of the nation struggled with the stagnant economy. Many of these economic gains, however, came to a halt as prices stabilized and dropped in the 1980s.”

If the oil embargo came about in retaliation of U.S support of Israel, then we can assume it ended when the U.S. abandoned that support…Oh wait?…It must have backfired because the American public came to hate the Arabs and gave even more support to Israel.

By the way, thanks Yves for the link last week to the 4-hour BBC series “The Century of the Self” on the manufacture of consent and the control of the public. Haven’t finished it, but you are right, it’s something everyone should see.

The notion of enlightened self-interest is a significant contributing factor to the systemic problems that we will continue to face.

It presupposes a lot more accessible, relatively transparent information and knowledge by market and transaction participants for self-regulation, or avoidance of predation, than has been the case. That is exacerbated by the troubling asymmetries found among financial market players in particular, where toxic risk transfer has been aided and abetted by willing parties (e.g., see 2008 issues), or by clueless rating agencies or others that were supposed to be the adults in the room. When the downside risks for insiders have been mitigated by extracurricular or shady means or by questionable legal tools such as non-dischargeable education debt in bankruptcy, or by a DOJ unwilling to prosecute, then why would anyone expect that private credit approaches are going to improve the results for the average person?

Greenspan is the embodiment of putting ten pounds of BS in a five pound bag. He oversold his vision, or delusion, and sadly is not alone. His fellow travelers have set the world on a troubling path that is not likely to end well for the average person.

And then meekly admitted his failure after it was too late to do anything about his monumentally destructive failure of fiduciary responsibility. He also has been invisible in the discussions of any possible remedies for the “flaw” he noted.

It is hard not to give special mention to Alan Greenspan. The creator of the ‘Greenspan put’ , the use of interest rate cutes to support asset prices , the man who nurtured the DotCom bubble, the de-regulator – he was a pioneer in Wall Street worst practices. The Street loved him : the ‘Maestro’.

“His work and that of his colleagues call into question the assumption that was commonplace before 2008, that private credit flows are primarily forces for stability and predictability in economies.”

They ‘question’ while Michael Hudson demolished, long-form, in “The Bubble and Beyond”. With a much longer look at history… which compels me to ask, where’s the “New Economic Thinking”?

–

“LP: What measures can policy-makers take to restore balance and sustainability to the credit system? What do you think might be their costs and benefits?”

AT starts off with the politically obvious. Then spews how the supposed Major Financial Regulating Institutions, “Operating in this milieu”, “are now taking a much keener interest in” how to regulate.

He then recognizes(“Echoing”…”Alan Greenspan“) that de-regulated financialization was a bad idea, but only focuses on ‘control’ of the credit side. “But the alternative isn’t obvious” because he never considers that exceeded debt capacity cannot supply “yield” to savings. Even if debt-reset were recognized as the obvious alternative, nobody is ever willing to take losses.

Everybody wants to go to heaven:

http://youtu.be/0G-SqMDTbks

…but nobody wants to die. Spot-on, thanks!

and everybody wants to know the reason, but nobody will ask the question why?

Any monetary system with an interest component is inherently unstable and prone to boom/busts with an eventual destructive collapse at the end of its life–producing dire results for any society foolish enough to employ it.

From the post: “This basic aggregate measure of gearing or leverage is telling us that today’s advanced economies’ operating systems are more heavily dependent on private sector credit than anything we have ever seen before. Furthermore, this pattern is seen across all the advanced economies, and isn’t just a feature of some special subset (e.g. the Anglo-Saxons).”

The hockey stick pattern is a simple mathematical consequence of having a monetary system that absolutely requires exponential growth to function (via interest). What would be surprising (and an extremely ominous sign) would be for the pattern, at some scale, to not be present at all. It’s simply an exponential function mapped onto a graph that our monetary systems happen to mirror perfectly.

Of course a periodic and complete debt jubilees could obviate the need for monetary collapse (and probably societal collapse as well), but for whatever reason the powers that be don’t see that as a viable option, so horrific collapse and mass hangings/guillotines it will be.

I’m not entirely convinced that debt jubilees wouldn’t lead to societal collapse either or result in boom and bust cycles. You’d have people who would consume for consumptions sake and you’d have resentment from people who essentially had to pay for that consumption but “saw” none of the benefits. If you knew you weren’t going to have to actually pay for schools or houses or anything else it might make you less mindful of your decisions in pursuing them, in my opinion.

“You’d have people who would consume for consumptions sake and you’d have resentment from people who essentially had to pay for that consumption but “saw” none of the benefits.”

Isn’t this what we have now, with luxury consumption by the oner’s and resentment by the ninety-niner’s?

Only if you think the lenders are complete boobs.

The lender should be aware of Jupilee and that that into account. If you want some one too much money that takes too long to pay back, then the lender should take the hit. We already have something very similar, its called bankruptcy.

We already *have* boom and bust cycles. Debt jubilees are a method of handling the busts after they happen, mostly.

Paul Meli made the following comment on a 2013 Mark Buchanan article featured in Mike Norman Economics:-

http://mikenormaneconomics.blogspot.com/2013/11/mark-buchanan-actually-economists-can.html?showComment=1384543495126#c6481991655098392410

“It’s easy to predict financial crises…take a look at this graph…

https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/33741/FGEXPND.png

Every time the red line gets too near the green line we’ve had a crisis…check it out.

…with the last one the red line crossed the green line for the first time since WWII (probably for all history).

If that doesn’t mean we are screwed I don’t know what does.”

The article mentions Iceland at the end without acknowledging that the financial crisis was the direct result of deregulation and corruption. The banks were controlled by a small group of Icelanders who in turn made unsecured loans to family and friends. To keep the populace acquiescent, they provided loose credit to anyone who could fog a mirror for mortgages and Range Rovers.

Before anyone suggests Iceland jailed it’s bankers….There’s a great video from the New Years Áramótaskaupið Special that makes fun of foreigners.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=9GzgqO3CvcA

I don’t think we can evaluate today’s political economy using historic data on credit or anything else. We live in an utterly unique historical moment that has no precedent. This period features, in my view, rigged and/or managed markets as well as a very unusual financial structure that functions with lots of smoke and mirrors that deflect and absorb normal market forces particularly in the world of hedges and hedges on hedges.

Neo-liberalism has been mostly about de-regulated financialization. We can debate about the intention and/or motivation. From the extreme authoritarian use as a “bloodless” weapon of conquest and subjugation to the other extreme of truly believing that everything can be measured in dollars and “markets” are the ultimate and/or only venue for human interaction…but you can’t deny that there is an expanding awareness that the effects have been devastating for most and benefitted the ever fewer few…and all the “smoke and mirrors” can’t distract from the eventual recognition that nothing has ever nor will ever “grow” exponentially, in perpetuity(for ever and ever).

This was way too abstract for me. Especially in a world with few concrete options for investing all that private money, whether it is borrowed or not. In fact there is no there there in this article. When all you have is an ocean of credit and no place to put it, who needs a crash? Taylor was blabbering on like credit was some reality and it needed no other connection or context in an otherwise real world. What the whole abstract idea of credit needs is a social context. Say a 50 year plan. Talking about credit like it is some private property in and of itself is not just absurd, it is an abstract absurdity. Aaaargh.

Honestly all this stuff looks and stinks like complete BS*** to me as well. These people do not live in the real world; they live in an abstraction of an abstraction of the real world and the feel proud of themselves for being so “intellectual” and “objective”.

From Paul Krugman: “…and hard scientists who think they are smarter than economists…” This is what passes for “thought” among pseudo-intellectual economists. If all the stuff their ilk comes up with looks like complete garbage to you, it just means that you have a well-calibrated sense of reality.

Real security will not be achieved by believing in this fraudulent financial system. Security will only be achieved by investing in your friends and neighbors, and by getting things like solar panels, rabbit hutches, and plenty of ammo.

Isn’t “credit” a “real” thing?

Any “credit” given to me, is an “asset” on someone else’s books. This is the reality, that their accountants use to show how much money they are making. When they don’t get it back, they use the loss of that credit payment, as a reason for their reduction in tax liabilities.

All the financial services companies and even merchantile companies, have this “credit” on their balance sheets, showing them their “earnings”, real or implied. Without these implied assets of owed credit payments,they would be insolvent.

It seems to me that “credit” is in lieu of money, but really the same thing in practical purposes. Even in the “real on the street” sense.

It is like,” I want to sell you a car or a refrigerator, but I know you are broke because your job sucks, but to keep the ball of wax rolling, here is a line of credit….. you can pay me later.” Too bad your job still sucks, and your first born is really no value to me…. But these credit columns really do make my bottom line and allow me to keep drawing on my accounts .for day to day stuff.

I think what you are saying is correct – that effectively credit and money are the same thing and for all financial purposes they are both (still for now) “real”. The problem raised above is that credit has exploded and it is creating a new untested and off-the-rails economy. Maybe one where there will be so much liquidity that money finally is reduced to being only a medium of exchange – at a rate set by some global mechanism – and ceases to be a store of value. When the world is awash in money, other mechanisms will be required to regulate trade and distribution because prices will unreal by any standard. And money will not command any interest. Can’t afford it? Here, here’s all the credit you need. So in this new world what happens to old-fashioned horse trading?

We’ve been over this. It is largely a symptom of falling real wages.

These so-called problems could be easily solved.

Take all the bad debt, load it into a rocket and launch it right into the sun. Once it leaves earth orbit, the sun’s gravity will do all the work. You wouldn’t even need all that much fuel. When it gets close to the sun, if it doesn’t melt, it’ll disappear. Do you know how big the sun is? It’s a lot bigger than it looks (but don’t look right at it or you’ll really hurt your eyes, I feel obligated to say that out of an abundance of caution and politeness). Anyway, it’s huge, the sun that is. The rocket would disappear, along with all the bad debt and even good debt. It would all disappear.

Why is this such a problem? I don’t get it. They launch rockets every week. There’s a lot of debt, but there’s a lot of room in something like the Saturn 5 rocket they used for the Apollo missions. it may be hard to remember how to build something like that, but it’s probably not impossible. They did it once before.

So what about all the people who owned the debt? you just give them new money. What would they care. That’s all they want is the money. They don’t care about the debt. They might even like to watch the blast off and the rocket shot. That would be cool. I bet some of them would cheer

But (not so) Crazyman

They say every dollar IS a debt! So if we launched all our dollars into the Sun, what would we buy stuff with???

========================

“If the Federal Reserve desires to increase the money supply, it will buy securities (such as US Treasury Bonds) anonymously from banks in exchange for dollars. Conversely, it will sell securities to the banks in exchange for dollars, to take dollars out of circulation.[57]

When the Federal Reserve makes a purchase, it credits the seller’s reserve account (with the Federal Reserve). This money is not transferred from any existing funds—it is at this point that the Federal Reserve has created new high-powered money.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_dollar#Means_of_issue

OR, as they say, everybody’s debt is somebody’s asset! (funny how that actually didn’t work, and all the “capitalists” wanted to exchange their debt, which I sarcastically note was freely bought and sold on the efficient “FREE MARKET” – – for those boring. low yield government bonds…)

Now, as far as I can figure, you gotta already have a whole bunch of dollars, “securities” or debt (or just to be unclear – we’ll call is debtdollars, to get your hands on more debtdollars). The FED won’t “issue” (AKA give or – lol – loan any to me) but if you have enough of these debt dollars you can buy all the sex, drugs, and rock&roll you could ever want. (see “Wolf of Wall Street)

Whats funny is the bunch who go on and on about how the Treasury can print all the debtdollars they want….never print any for me (or 99%)…

the only risk would be if something went wrong and it missed the sun.

Jesus, all that debt floating in space. Even though it’s huge, it would be too small to see from earth.

What if the six months later, when the earth was on the other side of the sun, the earth somehow collided with all that debt. Oh man. That’s like the inverse of winning the lottery. that would be bad.

You could try dressing nicely and walking up to a Fed window with a coat check ticket. Who would know if they did or did not lend you reserves for it? M3 has not been published since 2006, so perhaps no one really knows how much private credit is out there. It would probably take an army of auditors to verify and price the collateral.

That is Samuelson-Greenspam smoke and mirrors opiates to confuses the masses. Using their language and definitions explains their chimera, not reality. The FRB has made reserve requirements negligible for things like checking accounts. So the “real money” creator in the US is the bank which makes it out of thin air with a debit and credit. Since 2008 the banks “lend” money to the FRB short term while the FRB goes long long term Treasuries.

Craazyman,

I have a simpler solution. Download all the debt into a single file and then beam the information into the sun (using satellite wavelengths or whatever), where it will be destroyed.

Saves money on the rocket and fuel. Clever, huh.

Or just put it all on a thumb drive, and toss the little devil on the grill with your hamburgers.

For most of you out there, Paul Sweezy, now deceased, the editor of Monthly Review, wrote exactly about this issue, the exploding credit/debt. I don’t remember whether it was the 1970s or the 1980s. For old-timers like me this is not a new insight.

Infinite frequency = a straight line.

Except for scale, isn’t this what Marriner Eccles talked about in the lead up to the Great Depression? It is not just leverage, but the use of credit to maintain lifestyle when wages do not keep up with profits. Eventually something has to give. As I recall, Eccles used the metaphor of a poker game where most of the players eventually ran out of chips, at which point the game stopped.

Yes, it’s exactly the same.