Yves here. This post makes some very good observations about the nature of uncertainty and the value, as well as the cost, of additional information. But it uses a personal pet peeve as the point of departure for the article, that of the so-called Trolley Problem. The people who pose it argue that the two options (saving four lives by throwing a lever that results in five people being saved at the cost of another person dying, versus saving four lives by throwing a fat man off a bridge) are morally equivalent, yet the fact that most people say they will throw the lever but will reject throwing the fat person off the bridge is a cognitive bias.

Hogwash. They aren’t comparable. The throwing a fat person off a bridge (to stop a train) is presumably meant to eliminate the “what about me jumping off the bridge” option. Second, I’d wonder if I could in fact succeed in shoving someone over. And third and potentially the most important, if you do succeed in pushing the fat person in front of the train, you are unquestionably guilty of first degree murder. Tell me how you talk your way out of it if you are caught. You were knowingly planning to have the man serve as a human brake to the train and that that would be fatal. By contrast, if you flip the lever, you can say “I was trying to save five people” and profess uncertainty as to what would happen to the other person who winds up getting killed.

In fairness, the article does treat the two cases as representing more differences from an informational perspective than most who use it as an device do, but not as pointedly as I’d like. So please try to take the horrible Trolley Problem in stride and focus on the meat of the article.

By Cameron Murray, a professional economist with a background in property development, environmental economics research and economic regulation. Cross posted from Fresh Economic Thinkings

Ignorance of the distinction between risk and uncertainty lies at the heart of many economic conundrums, particularly dynamic behaviours through time. Yet the critical importance of this distinction in predicting economic behaviour was clear to prominent economists of the 1930s, including Shackle and Knight. Knight wrote that

… that a measurable uncertainty, or ‘risk’ proper, as we shall use the term, is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all.

Economists have now forgotten that a world of uncertainty generates a strong incentive to delay choices. We do not make immediate choices informed by the some probabilistic expectation of future outcomes. We usually can’t even know the potential scope of future outcomes. That means we delay choices to keep options alive, miss good opportunities, and sometimes commit to poor investments. Because time is irreversible, unlike in economic models, when we commit to decisions matters as well as the decisions themselves.

But the ignorance of uncertainty is evident in other social sciences as well. Approaching problems in philosophy and ethics without acknowledging uncertainty has lead to many seemingly intractable puzzles that are easily resolved in a world of uncertainty.

I hope that observing the crucial role uncertainty plays in these contexts encourages economists to take the concept more seriously and see the economy as a dynamic environment, rather than a static one.

In ethics, the Trolley Problem has occupied the minds of philosophers for decades. In its simplest example the puzzle is as follows.

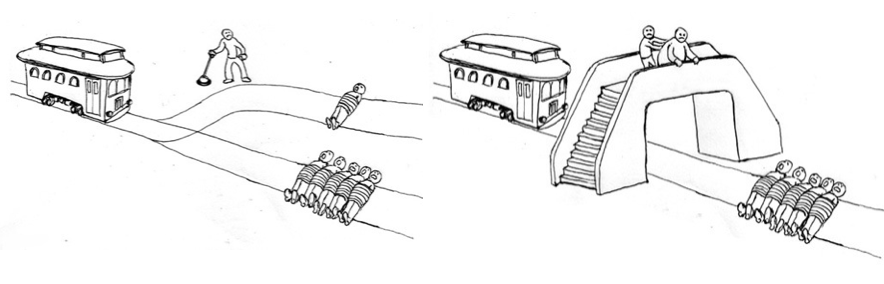

In Scenario A a trolley is barreling down the tacks toward five people who will be killed unless the trolley is stopped. Luckily, there is a fork in the tracks, and by simply pulling a lever, the trolley can be diverted onto a second set of tracks. Unfortunately there is a single person in the path of the tolled on this track who will be killed if you pull the lever.

The dilemma is whether you should pull the lever and save five people by sacrificing one? In surveys most people say they would.

In Scenario B you find yourself on a bridge next to a fat man where below the same dilemma is playing out, with a trolley hurtling down the tracks towards five people. The question here is whether it is permissible to pushing the person next to you onto the tracks if you knew it would stop the trolley and save the five people.

Most people in this scenario would not push the man off the bridge, even though the same welfare gains in terms of lives saved would be the same as Scenario A (so you know, 68.2% of philosophers would push the man to save the five). Some philosophers and psychologists put this down to a ‘dual-process’ theory and for some reason that two different setups invoke “the operations of at least two distinct psychological/neural systems”.

Fundamentally the incompatibility of these two outcomes arises because we are presented with a dilemma in terms of risk, or knowable probabilities. In fact we have point distributions at perfect certainty for each outcome. You push the fat man off the bridge (assuming away the logical problem that a man fat enough to stop a runaway trolley is somehow easily able to be pushed off a bridge) you have a probability of 1 that the man will die and the trolley will be stopped. If you don’t, you have probability 1 that the five people on the tracks will be killed.

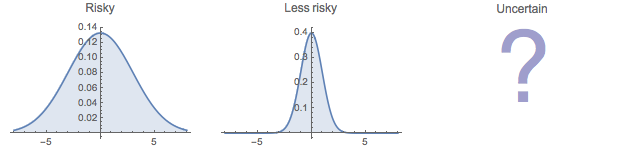

When you add risk by looking at possible probability distributions of choice outcomes you can generate the a balance of risks that predicts survey responses. This is a step in the right direction, since we know it is very difficult for people to comprehend the idea of perfect certainty. But it still overlooks the dynamic nature of true uncertainty.

Let us now look at the question in terms of uncertainty. For a start, how do we know the trolley is out of control? Is it possible to delay the decision to get more information?

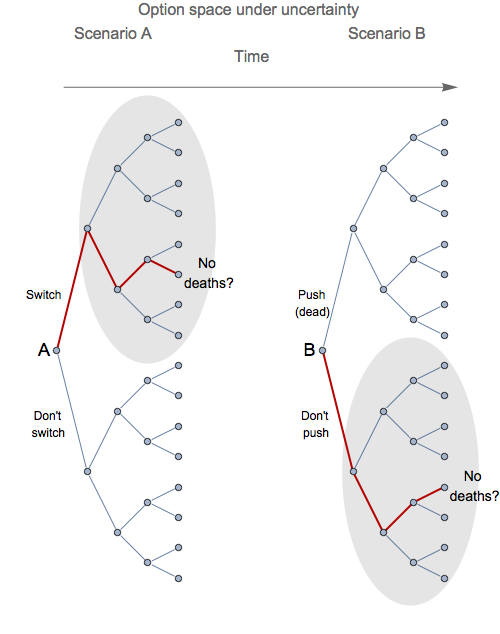

A very simple resolution to arises when we add a time dimension to the problem, which is what is required under uncertainty. We can think in terms of an option-tree expanding over time, with choices unable to be fully anticipated in advance.

We can see in the diagram below that in Scenario A, switching the tracks leads to a new situation that opens up the set of possible choices in the grey shaded area while eliminating others. Switching the trolley onto the side track buys time and keeps options open without killing anyone.

In Scenario B, most people choose not to push the fat man. Here what the are doing is buying time before anyone gets killed. Even after the decision is made not to push the man, there will be time available for many other as-yet-unknowable situations to arise.

People are making choices in a way that allows them to navigate through a choice space over the irreversible dimension of time. I’ve highlighted in red a possible path for each scenario that could be envisages in the mind of somewhat making choices in a world of uncertainty. In both cases there is an unknowable chance that a resolution to the dilemma will involve no death if the dynamic choices that arise are navigated appropriately. But choosing to push the fat man in Scenario B eliminates the option of resolving the situation without any deaths.

The whole rational of making decision in a world of uncertainty revolves around keeping options for desirable outcomes open, and often this involves buying time by not making a decision at all.

We know that buying time to keep an option open is a strong impulse. In experiments where participants are given the choice of which of two identical drowning swimmers to save, knowing they can only save one, many are unable to make the decision in a timely enough manner and instead spend their time searching for better information in the hope of maintain the option of saving both, but in doing so letting them both drown. Because the choice to commit to save one swimmer is associated with a commitment to allow the other to drown, the logical choice is to delay to maintain the option of saving both.

In military training overcoming this instinct to delay choices to keep options open forms a integral part of the psychological training. Soldiers are known to delay making any choice in high-stakes combat dilemmas, what amounts to ‘freezing’, or in many cases they shoot to deter rather than to kill, to keep open the option of finishing a battle with fewer deaths in general.

In criminal behaviour, Becker’s expected utility framework has been called into question due to the radical difference between human behaviour in a world of uncertainty versus a world of risk. Increasing chances of being caught and increasing punishment if caught are substitute methods for changing probability distributions of expected outcomes in a world of risk, but in a world of uncertainty they will have far different effect on criminal decisions.

The same logic of uncertainty can be applied in social psychology to understand the bystander effect. The bystander effect in which there seems to be an inverse relationship between the number of people witnessing a victim in need, and the number of people offering help. Various reasons for this empirical phenomena have emerged, with the idea of a diffusion of responsibility dominating explanations.

But when we dig a little deeper we can see the logic of uncertainty at play. Repeated experiments on the bystander effect show that the degree of ambiguity is a crucial determinant of the willingness to assist, with reaction times being much slower in the presence of more ambiguous situations. The logic of how ambiguity, or uncertainty, results in the bystander effect is as follows

…most emergencies are, or at least begin as, ambiguous events. As the bystanders are deciding whether an event is an emergency, each bystander looks to the others for guidance before acting.

… Seeing others remain passive causes the bystander to interpret the ambiguous situation as non-serious.

So it is not that anyone does not want to help, but as each person individually chooses to delay their actions to gain new information, they observe others doing the same thing. By observing others they gain the new information that the situation is non-serious, and hence as a group they ultimately choose a path through the choice space over time that resolves to a belief that the situation is a non-emergency.

What happens as people delay choices here is a cascade of new information that changes the decisions of each individual and the group as a whole. In sociology there are many simulation models of these type of choice cascades, from standing ovations, to riots, and other herding behaviour including musical tastes, and crucially for economists, asset market speculation.

Uncertainty is a primarily a concept about choices in a dynamic environment. Here I have shown that human behaviour is adapted to our dynamic irreversible environment, and as such, uncertainty is required to understand behavioural logic, morality, and sociability. Moral puzzles resolve easily in an environment of uncertainty, and many psychological phenomena, from soldiers freezing in battle, to the bystander effect, to our taste in music, can been seen to arise from a result of human tendencies to delay decisions in order to cope with uncertainty.

It is not just economists who have known that uncertainty is tremendously important, but then all but ignored the concept in their analysis. Given the high stakes arising from political choices based on economic analysis, putting uncertainty front and centre in a new dynamic economics is critical.

Grinds my gears that he goes with “68.2% of philosophers”, an accuracy which, I’m guessin’, way overstates the certainty of that outcome.

Or maybe it’s my irony meter that’s off-calibrated today.

Crap, I meant ‘precision’, not ‘accuracy’, stupid ambiguity…

I actually visited the linked article, and I learned that the authors assigned a certain amount of uncertainty to the number: 68.2±1.7%. See? It’s scientific! Plus, zombies are mentioned in the article! I am not making this up; go take a look at http://philpapers.org/archive/BOUWDP. The article is dated November 30, 2013, but this must be a typographical error for “April 1, any year”.

They had fewer than 1000 respondents, they could’ve reported with 0 uncertainty. Hmm.

Happy All Fools Day to You, as Well!

… Seeing others remain passive causes the bystander to interpret the ambiguous situation as non-serious.

Maybe but the question in my mind would be: “Am I the most qualified person to help safely?” if, for example, a person appeared to be drowning. With just a few (or no) other people around, I can quickly make that decision.

“Am I the most qualified person to help safely?” Sounds like a trained response question; I imagine I go by first Can I?, followed by Do I?. Doing the first can take you down an analysis tree, and as I’ve aged I’m more careful with the second.

Twenty years ago I witnessed an auto accident from two cars back, didn’t look terrible (and wasn’t). Cars stopped in 3 directions, I got out of my car as did several others, and a guy in one car has rolled down a window and is struggling (with his jammed door) and yelling for help. So I walk up, passenger side, talk to him. Back seat empty, driver is conscious but stunned, bleeding from head but not much. Driver of other car was out, ok, had a cell phone and was calling it in, and I knew the fire/ambulance was a half mile away. There’s a half dozen people out of their cars but not coming near. I’m just trying to calm the passenger, who is fixated on exiting the car, and when he starts coming through the window I help him, and 30 seconds later help arrives. I go back to my car and stand and watch as the road is frozen for the moment, and a man comes up and starts talking to me. Says he’s an EMT, was in the car stopped behind me, understands why I helped but that it’s better not to: injured parties safety and my liability. Oh yeah, I didn’t stop to think over that Good Samaritan stuff for my state and this situation.

This happened on the day we moved into a new town and state, and my HS daughter was in the car waiting for me, she started school the next day, as a senior in a new HS. When she came home she told me I was a hero that day at her school. Driver and passenger were seniors, and in cafeteria they talked about their accident, and how a dozen people were watching and not moving as they called for help, and one guy had walked up and helped, and my daughter was able to tell them who it was. For her it was a great introduction to new community.

You were a hero!

Your story reminds me of a guy who was on his way to a job interview when he saw a woman with car trouble. He had no time to help but did so anyway.

He arrives at the interview late but the interviewer was not there. She soon arrives apologizing “Sorry I’m late, I had car trouble …”

“He who loses his life … will find it”

We generally like to judge people who make the wrong choices in times of stress but the reality is that most of us do not know how we would really react in a time of stress. In my experience, most people in such odd situations just freeze and do nothing. The reaction will be based on a slew of stored data which include knowledge, experience and prejudice. So we could posit that those who react are:

-The genius who can quickly make the right choices across the outcome tree. (rare)

-The risk taker for whom the logic tree and branches of outcome are non-apparent due to a short-term thinking brain. (less rare)

-The narrow-minded for whom there is only 1 course of action and would follow his same convictions in all situations.(quite a few)

-The experienced and/or trained to act in such a situation (rare)

Scamtrack

holy shit is this a real mind wank or what? wow. If those dudes tied to the rails were 4 philosophers and that fat dude was a 5th philosopher I think most people would think somebody was making a movie and they’d laugh as the train was coming. the philosophical question is how they’d react when they found out it was all real? They’d probably just think, “How did 5 smart dudes get themselves into that situation?” Its hard to answer.

OK, really – a person can be so fat that the person has enough mass to stop a trolley car!?!

OK, I’ll go with it.

So, in this world of gargantuan fat people, what is the probability that the fat person just happens to be next to you, and our “tie skinny people to rails perpetrator” didn’t find one fat person to tie to the tracks?

If your point is probability, don’t use improbable examples – This is America – land of bipedal hippos.

After all, if the 1st person tied to the tracks was huge, that would stop the trolley and no need to shove another fat person onto the track. And if the first was skinny, and the second huge, again, the trolly would be stopped, so you would only be giving up one skinny while having to sacrifice the fatty on the bridge, so no net saving of people as the trolley would be stopped anyway.

Not to mention I didn’t see an escalator to the top of the bridge – all the fat people (actually, all the people) I know skip the stairs and look for an elevator or escalator – I didn’t see a Haagen Dazs shop on top of the bridge either, so we have no plausible incentive for the fat person climbing the stairs….so the scenario is highly, highly implausible…

I’ve never even seen a trolley car except in the movies. That’s why I thought this must be a movie and not reality. If it’s a movie anything can happen and there’s nothing you can do but watch. If it’s real, there’s no way a fat man can stop a trolley, since there’s no trolleys any more. QED. This is so contrived as to be unrepresentative of real moral dilemmas. The real dilemma would be whether to run like hell and tell the 4 guys to get their asses off the tracks cause a train is coming or just call the ambulance and run yourself, the other way.

I kid you not. I was in a Lexington Ave. subway station 2 years ago and some idiot jumped down on the tracks to pick something up that he must have dropped. Then a train came around the curve toward the station. He tried to jump back up to the platform but it was too high, about neck level and he fell back down. So I was standing there and grabbed one of his arms and some dude grabbed his other arm and we yanked him up on the platform so hard he about flew through the air toward the station wall like a bird, with the train coming 60 yards away blaring its horn. That’s close enough for me. It fukkin shook me up just thinking bout it for 20 minutes afterwards. If 4 philsophers tie themselves to the tracks as a test, I’d say “Guys. I mean really. Cut your damn ropes, Get the fuck up and run.”

The swimmer article he links to is worth the look. In mediation, we use open-ended questions to reveal the issues under the positions. Iterated games have different winning strategies than single-match games, and one of the first things to establish is whether the parties want a future relationship. (I can’t remember who said that the point of the game is to keep playing the game.)

But some decision situations require faster outcomes. The point of Boyd’s OODA loop is to re-orient faster than your opponent and speed up the decision cycle. The use of more categories allows shorter calculation time, which is a selection criteria. And then to commit resources with what Mae-Wan Ho terms a single degree of freedom. Aiming for the middle of two targets is usually a miss.

Sozou: On hyperbolic discounting and uncertain hazard rates. This article is available through NCBI online, and is a link from Bayesian analysis to the hyperbolic discounting implicit in Herrnstein’s Matching Law. It’s a frame of reference that bears fruit.

I’d like to make two points regarding this exercise. First, the author builds his case on an evaluation of two scenarios that say that the one or four people WILL be killed, and then introduces the possibility that they MAY be killed. So he asks one question and assumes that those polled will answer a different one. Second, who can deny the point raised by Moneta’s statement: “We generally like to judge people who make the wrong choices in times of stress but the reality is that most of us do not know how we would really react in a time of stress. In my experience, most people in such odd situations just freeze and do nothing.”. While I have never sought to conduct a study as to how to prove the accuracy of that statement, I suggest it is another example of how economists tend to constantly try to prove that things we see with our own eyes are theoretically impossible. IMHO, the author asked an ambiguous question, which is logically going to lead to uncertainty, and then makes a great effort, uses a lot of words and too many diagrams, to prove that Moneta’s real world observations are correct – kind of garbage in, garbage out. BTW, Moneta’s observations are identical to mine.

A little tangential, but:

My Environmental Law professor was proud of his contribution to the briefing and outcome in US v. SCRAP, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/412/669/case.html. But by the time I was in his class, he had discovered that the money side had all the features and benefits sewn up. So as a trained economist, he put us to discussing this issue: Posit a beach on a summer day. Many people out taking the air and sunshine. A newcomer sets up his towel and umbrella, and fires up a boom box blaring loud music. Query: how much to the other people previously enjoying the sounds of waves and gulls have to pay the newcomer to turn off his radio? Same setup, but the action that the others have to regulate is smoking a rancid cigar. Formulae and parallels were provided from which one was supposed to construct an argument for how much the “right” of the person who the rest wanted to forgo his noxious and obnoxious behavior was “worth.”

Per the prof, one was not allowed to question the setup, particularly the arbitrary assignment of the “right,” here to pollute and perturb, to the person who disturbed the quiet enjoyment of the rest of us. I guess that’s why a lot of us got Cs on our exams, since that initial assignment or brute taking of “rights” pretermits the real substantive discussion that controls all the rest. Not that in our neolib world there is any possibility of having that initial argument…

Nope nope nope. The trolley problem, properly described, does not contain any ambiguity about the outcome of the decision, nor is there any room for hesitation. Both scenarios guarantee that 4 people will die if no intervention is made and 1 person will die if the only possible intervention is made; this is a make-believe example with artificially constrained possibilities, designed to get at a very specific kind of problem.

That specific problem is the moral intuition that harm caused by actively causing something to happen is less blame-worthy than harm caused by letting something happen (when we have the power to stop it from happening). The discrepancy between the proportion of people who would choose to intervene in case A vs in case B is down to the mediation of the action (through a switch mechanism) in case A vs the direct pushing of the fat man in case B. The second intervention “feels” more like murder, even if the outcome is the same and equally valid in single-iteration utilitarian terms.

These problems illuminate the dual systems of deontological (don’t cause trains to run people over, for any reason) vs consequentialist (reduce the harm for all involved wherever possible) moral reasoning. The relevant economic concept to which these problems can be applied would be in the area of rights and responsibilities under emergency circumstances, and the fair distribution of unpredicted downsides. This article either deeply misunderstands the problem or deliberately reformulates it for entirely different purposes.

This is why economists need to get out more. Anyone visualize themselves in a situation when told as a story. And if you’ve been in or near an accident (as I have), the visualization can be very vivid.

The idea that you can dismiss how much effort it would take to push a fat person off a bridge shows how unrealistic this is. The trolley problem is posited as what would you do, and that entails seeing yourself in that situation, with all of your personal issues. Even touching someone you don’t know is a boundary violation in our society that is not present in the “pull the lever” option.

Agreed. On the one hand the scenario is considered “real” enough to evoke responses sufficiently visceral as to be meaningful, while on the other hand, everyone is assumed to “get” the fact that the scenario isn’t real at all and can’t possibly include such things as performing feats of impossible strength (and outright murder at the same time), etc.

Much easier to solve the problem of jumping and not jumping at the same time.

Pfui.

But as a means of explaining the phenomenon of such choices, uncertainty and time restraints, and what they can indicate conceptually, it does have value.

Enjoyed the read, but I’m not sure what explanatory value ignorance possesses for our contemporary system? I’d say blurring risk and uncertainty is a central tenet of financial fraud and prisoner abuse and the general looting in our system. “oops” plays better after the fact, especially in a world where comfortable intellectuals don’t like holding people in positions of power accountable.

As far as surveys, it’s a very simple behavioral process at work. We are a social species generally wired to passively tolerate more suffering than we actively cause. The issue is not uncertainty. The issue is certainty. Pushing a man in front of a train is murder. Trying to complicate the matter misses an elemental understanding of human behavior. Everyone who would shove the fat guy would pull the lever. But some people who wouldn’t shove the fat guy would be willing to pull the lever.

That’s why systemic, institutionalized oppression is such a problem in the midst of our modern enlightenment. People who would never actively engage in overt racism or slavery or sexual assault or perversion of rule of law are willing to passively enable such systems as long as their hands are kept mostly clean – as long as they have a plausible story for why their actions contribute to ‘welfare gains’. These two outcomes are not incompatible. It’s how morality works, a technically complex but conceptually quite simple balance of ‘Good’ and ‘Evil’. If Good > Evil, then do it. If Evil > Good, don’t do it. Since Evil is generally greater than zero, it involves some kind of weighing of the two.

Which is why first secrecy, and then Self vs. Other when secrecy can no longer be maintained, is so important to the authoritarians, and why obfuscation is such a tasteless activity among educated people who ought to know better. If we’re making calculations about costs and benefits, gains and losses, good and evil, blurring some of the losses (or exaggerating some of the gains) can make it appear as if there is a net welfare gain even when there really isn’t.

Decision making is all about ignorance. We decide based on imperfect information. I don’t see how you can argue that this is not relevant.

Lack of total information is not the same thing as ignorance.

We have ‘enough’ information about how our system works to come to reasonably confident conclusions.

The CEO defense is not a good faith explanation of lack of information. It’s an attempt to sweep things under the rug, to justify not honest mistakes but rather bad behavior.

The question turns on the question: can we really observe ourselves objectively and know what we will do in a given situation? The ideal is established but unspoken: it would be best if nobody died. Not everybody believes that! On the contrary, people see their clan as superior and others as inferior quite routinely. Would you save the five strangers by diverting the train to kill your mother? Suddenly with more information, the numbers argument falls away when one can make a qualitative judgement.

The quickness to decide is really the quickness to judge. For example, are we even sure that the train is runaway? Will pulling the lever circumvent the engineer who is ready to stop? Sure, these are lame questions, but not any more lame than trying to use a highly improbable crisis situation with zero alternatives and even less time as a paradigm for deeper meaning. This is a lose-lose framework, and the question is ‘Is one a morally negligent accidental bystander by choosing A instead of B?’ What it suggests is that action and inaction can both be negligent, even though we had no role in creating the situation. The family of the fat man or the single person will sue for negligent death, because their loss is personal, not theoretical, and would not have occurred without willful action. Likewise, the family of the group of five could sue for failing to act. You could have saved their lives and chose not to. Neither case would get far in court, of course, since the choice is only to react, which is a weird test for free will and moral judgement. Jumping in from of the train to stop it is probably the only choice with moral integrity, assuming you could stop it. If there were only one track, and you could save your mother, would you jump in front? Let the question of fear be real.

Sometimes there is no right or wrong answer, just a choice, which gets back to the structure of the question. What can it illuminate? Is choosing vanilla instead of chocolate ice cream not as much a part of the butterfly effect? The urgency from which we can see the consequences of our choices does not change their impact. On the contrary, risk and uncertainty are a result of cause and effect and our lack of awareness of cause and effect.

The only honest answer to the question is ‘I don’t know.’ And, fortunately, we will probably never be put in such an extreme situation. Whatever we decide, however, is always based on what we think we know. And, the consistency or inconsistency of different situations are similarly a self-created choice. The ability to control outcomes is based on assumptions that may or may not be true, thus the difference between risk and uncertainty is ultimately a projection, even though each situation was created by the actions of others in society. For example was this an attempt to kill 5 or 1 person, or a random psychological attack on the bystander? A teacher posed a problem for students. Did he actually teach them anything, or push them into confusion based on their naiveté? Knowledge of good and evil is a long and winding road. It troubles me how much time is spent on this question, when it can only teach so little, but maybe by embellishing it, then it could have more value.

Capitalism is a perpetual choice to save oneself at the expense of others. A more accurate question is, if you are both tied to the track, and pulling the lever will save yourself and kill an innocent child, would you pull it? The consequences of capitalism fall on the next generation.

There is another more immediate reaction in most people…. For them to throw someone off the bridge they must interact with that person, either the fear of confrontation, or the moral impulse not to (directly) kill, or the a sense of empathy for the person who they can see, fighting or begging not to be thrown off, would impede a substantial portion of people from throwing anyone off a bridge.

Steven Haidt made an interesting observation, the greater distance a person feels from a decision they have to make, either because they have anonymity, are part of groupthink, or are acting through intermediaries, the less likely their actions might be moderated by morality or with empathy. Hence more people might be inclined to pull a lever, and politicians more inclined to enact policies that steal from the anonymous many to benefit their close friends etc.

Some people say that empathy is not a strong influencer of human activity, so that it should not be relied upon. I say that empathy should be encouraged and cultivated and celebrated, so that it can be strong enough to influence our actions. Any smart person can create rationale to justify hurting another, but if they had the heart to look in their eyes and see their suffering, they might be able to feel that their actions are wrong.

The Self-Driving, Fly by Empire Wire, Economy

Essentially, by implementing the dc economy globally, to increase the efficiency of feudalism, breeding compliance with RE control at the expense of economic mobility, the critters have entered a positive feedback loop with climate variability, kind of like grabbing 480 3-phase and being surprised that it won’t let you go until you are fried. Clinton and Bush are not getting all the money by accident. They can’t help themselves, any more than the herd they represent.

The central bank is a hero, for throwing savers under the bus. Just ask Warren Buffet, as he doubles and triples rents in the Bay Area, to throw people on the street, and build another empty building for Chinese and Russian money launderers. It’s always a war in the empire, over who gets to employ its economic slaves, to build a memorial to themselves. Of course government rewards compliance and makes an example of dissent, to breed automatons. The Millennials aren’t any different from the Boomers.

Maglev, controlled by dc, can only fail, but it creates a lot of make-work, RE inflation and relative income deflation. Pissing away opportunity ends badly, for both the herd and its predators. Not selling to homosexuals is a stupid business practice, but so is not discounting it to a couple raising children out of poverty, as is giving Buffet a free pass all together. Self-driving cars is the ultimate irony of the lie that is the American Dream. Like every majority, this one is volunteering for slavery, to the past.

Equally yoked in marriage is one thing; equally yoked in a herd is another. A little common sense goes a long way. Basic physics tells you not to place all that weight in one place, a shining city on a hill, especially on the coast. The whole point of HR is to reward compliance with credit and penalize dissent with debt, the only difference in which is the disposable toys, and the price of RE up the slope from the landfill.

The Dust Bowl/Roaring 20s/Great Depression/WWII was no accident. From the perspective of the planet, it wasn’t even separate events. Whether this planet is 5000 years old or 5 trillion is a matter of perspective. From the perspective of the universe, it is a blip in a vortex. Some values are timeless; the equals sign is only a limit switch if you make it so, in your mind.

Only the physical universe you see, in a telescope and a microscope, calculates itself, with gravity. If a dc computer is one point and an ac computer is another, what is the third point?

That sin wave is a circle with a switch, a multiplexer. Time is a derivative, which is why it travels in one direction, and why the critters are always looking in the rear-view mirror, increasing efficiency. The empire is noise; learn to recycle. You shouldn’t be surprised that the reward for responsibility is more responsibility, and being hunted with technology. If you want bridges between the social event horizons, you have to build them, in real time, because only you are at your location in time, despite everything and everyone around you, telling you otherwise, what they see in the mirror.

Funny, where you can go, if your mind can leap, and who you find when you get there. The critters, always travelling expediently downhill, into the hands of predators building the path before them, cannot tolerate reality, so don’t waste your time.

The Trolley Problem with Harry Schearer

It sounds like waco RANDISM.

So the Trolley dictum may instruct some economic choices such as how to inject liquidity to an economy; top down or bottoms up.

Maggie Thatcher is famous for “There Is No Alternative”.

Posers (poseurs?) of problems like this are teaching the same false lesson, but not as effectively.