By Jérémie Cohen-Setton, a PhD candidate in Economics at U.C. Berkeley and formerly an economist at HM Treasury. Originally published at Bruegel

What’s at stake: Larry Summers made an important speech a few weeks ago at a Peterson Institute conference on the productivity slowdown arguing it is hard to see how recent technical change could both be a major source of dis-employment and not be associated with productivity improvement.

A Paradox

Larry Summers writes that it’s really hard to square the view that the “new economy is producing substantial dis-employment” with the view that “productivity growth is slowing”. The fact that you move through an airport with much less contact with ticket takers, the fact that you can carry on all kinds of transactions with your cellphone, the fact that you can check out of an increasing number of stores without human contact, the fact that robots are increasingly present in manufacturing, make a fairly compelling case that the increasing dis-employment we see is related to technical change. And yet, if technical change is a major source of dis-employment, it is hard to see how it could be a major source of dis-employment without also being a major source of productivity improvement.

Adam Posen writes that it is a real puzzle to observe simultaneously multi-year trends of rising non-employment of low-skilled workers and declining measured productivity growth. Either we need a new understanding, or one of these observed patterns is ill founded or misleading. In my view, we should trust labor market data more than GDP data when they come in conflict—workers are employed and paid, and pay taxes (usually) so they get directly counted, whereas much of GDP data is constructed. Thus productivity, as the residual of GDP minus capital and labor accumulation, is much less reliable than the directly observed count of workers.

The Accelerating Mismeasurement Hypothesis

Larry Summers writes that it is at least possible that there are substantial mismeasurement aspects and that there is a reasonable prospect at accelerating mismeasurement as an explanation for some part of this puzzle. As we move from tangible manufactured goods to intangible services, it seems to me plausible that the fraction of the economy where we’re doing really badly on quality is likely to be increasing and that means that mismeasurement is increasing.

Larry Summers writes that it’s almost impossible to disagree with the view that the price indices overstate inflation and therefore the quantity indices understate quantitative growth. It is significantly more contestable whether that process has accelerated or not, but I don’t find myself with an alternative way of thinking about the dis-employment through technology which seems to be a pervasive phenomenon and that leads me to assign more weight to the mismeasurement hypotheses than I otherwise would. The other explanations could be that there really isn’t a set of dis-employment events or that there is a production function that can generate higher productivity together with slower productivity and more dis-employment.

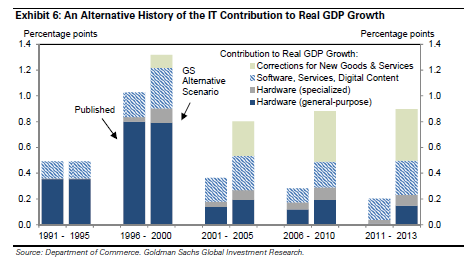

Jan Hatzius and Kris Dawsey write that increased measurement error might indeed account for most of the ¾pp decline seen in consensus estimates of trend productivity growth over the past decade. The shift in the IT sector’s center of gravity from general-purpose IT hardware to specialized IT hardware, software and digital content—where it is far harder to measure quality-adjusted prices and real output—may have resulted in a growing statistical understatement of the technology contribution to growth.

- The sharp slowdown in the measured deflation of semiconductors and computers may be a spurious consequence of shifts in industry dynamics rather than a genuine slowdown in technological progress. The lack of any significant quality-adjusted price decline in more specialized IT hardware industries also looks implausible. Our best guess is that these two issues together are worth about 0.2pp per year on real GDP growth.

- The problems in the software and digital content industry are thornier but potentially more sizable. One is that the official statistics seem to make little attempt to adjust for quality improvements in these products over time. Another is that the proliferation of free digital content has arguably introduced a more extreme form of “new product bias” into the inflation statistics. These two issues might be worth another 0.5pp per year.

John Fernald writes that David Byrne at the Board of Governors plus various co-authors of his have done a lot of work on that and suggest that, indeed, this is important and it probably adds up to one-tenth or two-tenths of GDP. So, that on its own will not change the productivity numbers. Remember, the magnitude of what we need to explain is a slowdown after 2003 or 2004 of two percentage points on labor productivity growth and maybe 1.25 or 1.5% on TFP. So, one- or two-tenths won’t close that gap.

Ah, this I understand:

So both number have a plus or minus error range, and the error range on Counting Payroll is what (1%, 3%, 10%) and GDP error range is what?

Numbers without this qualification, error range are nonsense. They have spurious precision and little accuracy, because they mislead. When the error range is stated then we have a statement about both precision and hopefully accuracy.

Accuracy will always be suspect, but the trend of numbers useful if they are always calculated using the same method. However, if the method is changes, then the method of calculation need to be carefully examined, and the actual calculation, to determine if the results are repeatable by others, independently.

Falling productivity could also be a measure of the huge trend to service based employment.

Or possibly we have reached a limit on productivity? The dreaded S curve of all systems where the activity to increase productivity costs more then the revenue generated?

Just for the sake of discussion, I suspect there might be a major source of unproductivity hidden in that label “correction for new goods and services” in the graph above.

A few decades ago, corporations attempted to take advantage of the “learning curve” — i.e. the longer one works at producing a good or service, the better, more productive one becomes at it. This was empirically measured as time-to-completion, amount of waste per unit, etc.

This assumed long product cycles (e.g. car models were sometimes built for decades), and not too many variants — which are exactly the reverse of today’s approach.

It is especially evident in the “IT hardware” which the author considers at length: there are many variants on offer, and they keep being replaced by newer models year after year (the entire electronics industry, including household appliances, is like that). The same situation is present in services linked to new technology: just look at price plans from telecom operators — they are constantly altered and restructured; it seems to me that every price plan for my mobile and landline phones I ever had ceased being offered and was replaced by a different subscription model within a year.

If you keep changing the products or the services, and if these still must be manufactured or provisioned by human beings, then the possibility to move along a learning curve disappears. And productivity improvements evaporate as well.

This is likely a feature, since humans that know more and are more productive, will expect more pay. Therefore, remove the ability to advance.

The relentless effort to cut labor costs by getting rid of highly paid staff or replacing them with less-skilled lower paid staff must reach a point of diminishing returns don’t you think?

The dawning realization that everything is slowly being ‘crapified’ is another facet of the same process.

Management is not only making money by drilling holes in the bottom of the boat, they’re cooking the books to exaggerate the profits made by doing it.

The light at the end of the ‘recovery’ tunnel is getting dimmer.

Reminds me of that old joke;

“Doctor, it hurts when I do this?”

^^This I understand perfectly. Thanks.

“Management is not only making money by drilling holes in the bottom of the boat, they’re cooking the books to exaggerate the profits made by doing it.”

Exactly this.

–Gaianne

Why can’t we have both? Technological unemployment is undermining labors bargaining power and thus wages across sectors. As a result, many sectors do not invest in technology improvements, but rather find it cheaper to his low wage workers to conduct low productivity work. Additionally, as we see with a number of high profile mergers (Busch, Dell, now Dow and DuPont), elites are on a spree to pull up their oars and take as much as they can, while they can. I have to assume that share buybacks and dividends result in net increased savings as opposed to activity that would drive future GDP growth.

By wonderful coincidence, I am just re-reading one of my top 10 all-time favorite books–Industry and Empire by Eric Hobsbawm. Hobsbawm argues that the weird thing about the Industrial Revolution was that you had people with money investing, then re-investing, in machinery and techniques that boosted production in a way that was atypical of all previous historical epochs. People invest in increased productivity only if it produces higher profits. Hobsbawm believed that this was rarely the case, although for a host of reasons it wasn’t in late 18th century Britain. You needed an already monetized economy and a fairly large untapped market of consumers in order to make increased production and productivity profitable. With the global consumer population today tapped out and less and less access to money, it makes no sense to increase production, and with wages stagnant, productivity.

There should be no puzzling over the causes of decelerating labor productivity.

Gov’t spending, private “health” care and “education”, and debt service combine for an equivalent of more than 50% of GDP. These sectors have become a prohibitive cost and are a net drag on the remaining private economic activity, contributing to the deceleration in productivity.

Hyper-financialization of the economy and associated asset bubbles has led to debilitating effects on the economy from net rentier flows to the financial sector (and disproportionately to the top 0.001-1% owners).

A record low for labor share of GDP similarly reduces productivity by depriving 90% of the labor force of growth of purchasing power after taxes, price effects, and debt service.

Favorable tax treatment of unearned income vs. regressive taxation of earned income contributes further to the low labor share.

Prohibitively costly medical insurance contributes still further to the high cost and low share of labor to GDP.

Extreme inequality coincides with low labor share, asset bubbles, non-productive rentier speculation, and hoarding of overvalued assets at virtually zero acceleration of velocity in the economy.

Peak Boomer demographic drag effects after 2000-01 are also contributing to the slowdown in the growth rate of household formations, house purchases, consumer spending, the composition of consumer spending, etc.

The peak of the debt cycle of the Long Wave Downwave’s reflationary regime that began in the early 1980s. By 2007-08, the cumulative differential rate of growth of debt to GDP reached an order of exponential magnitude, thereby reaching the point at which growth of additional debt was no longer reflationary even at very low interest rates.

Peak Oil has resulted in (1) the energy cost of energy extraction being prohibitive (net energy declining and no longer marginally profitable) and (2) the differential change rate of oil consumption to GDP to prevent an acceleration of GDP when further constrained by excessive debt to GDP.

https://app.box.com/s/h0p6s4ye96k6cx7smn0r2te0giganyy1

https://app.box.com/s/xcult10g1qfq3qi9wobow4j4l6j0pu0o

A similar condition has prevailed in Japan since the late 1990s, as it did from 1930 until WW II and briefly thereafter (adjustment from the extreme distortion of the US gov’t effectively taking over the economy to fight WW II), and in the 1890s. These periods are characteristic of a deflationary regime of the Long Wave Trough.

The leading sectors in IT and now social mania and online retailing are now increasingly cannibalizing existing sectors (retailing, advertising, communications, media, distribution, etc.) but without contributing to net domestic growth of revenues, profits, employment, and purchasing power. Rather than the Schumpeterian “creative destruction”, we are witnessing “destructive destruction”.

Finally, accelerating automation of labor product has resulted in increasing deskilling of the labor force, which makes it virtually impossible for a growing share of workers to increase their productivity and thus retain gainful employment and increase purchasing power. The convergence of accelerating technological advances in robotics, Big Data analytics, AI, biometrics, bioinformatics, sensors, etc., will only exacerberate the rate and scale of deskilling of the labor force, including well-paid service workers and professionals, e.g., doctors, attorneys, nurses, and educators.

Unless we understand the Long Wave, the S-curve, the debt cycle, demographics, financialization, the drag from gov’t, health care, education, and debt service, and Peak Oil (system thermodynamics, i.e., net energy, entropy, and exergy), then we are left with academics sitting around puzzling about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin.

. . . The spirit of Barry Commoner?

Larry Summers knows there is a compelling case for technology being the cause of disemployment because he and everyone he knows encounters fewer service workers in their own lives, and who doesn’t spend their life traveling, going to movies and buying stuff on Amazon? But it’s more than a little one-sided – what about his barista, who has a Ph.D., or the bevy of home health care aides he has had to hire to care for his ailing parents?

And has he walked into a hospital lately? Nursing staffing is for sure way down but the number of people working there doesn’t seem to have fallen. I’d be curious to know how you measure productivity in health care anyway. If it’s just total sales $$/worker hours, then the data probably shows productivity going up in that sector even with increased staffing, though it’s hard to argue that the higher prices have made the product “better” or even “produced more efficiently.”

Also, the tech explanation for the decline in factory work saves him from the tedious task of having to explain to his liberal friends for the umpteenth time the math behind why trade deals, and globalization, are irrelevant and certainly not what is driving wage inequality.

And, the notion that the masses of good office workers are killing it productivity-wise like he is for 8-10 hours a day is more than a little naive.

Separately, Larry Summers writes that it’s almost impossible to disagree with the view that the price indices overstate inflation. Really? It seems like lots of people do.

My wife told me a few years ago that she had a hunch that what we’d see going forward was inflation of everything you absolutely need (food, fuel, healthcare, education, insurance) and collapsing prices for luxuries (HD TVs, smartphones, fancy cars, etc.). I think she’s being proven right. From the top, it’s hard to see inflation, especially as housing prices in most places are barely back to 2007 and adjusted for what little inflation there is stock portfolios are also just about back where they were. But if you are closer to the bottom, you see prices going up for things you need (with the exception of gasoline for reasons complex and partly manipulated).

Agree. Those at the very top of the heap still see bargains and deals galore especially for luxury items, and the rising cost of necessary items – food, utilities, rent – isn’t really apparent to them. They’re in clover, and they know it.

I have been stating for several years – here and elsewhere – that while I’m fortunate enough to be able to afford it, my grocery bills anymore pretty much stagger me at the cost. I could buy more cheaply, but even so, I’m not shopping in Whole Paycheck and similar.

I simply can’t imagine how the “average” family of four does it. Needed consumables continue to rise, including clothing, toiletries, cleaning products, etc, in the so-called cheaper places like Target and WalMart (I don’t find those stores all that cheap anymore).

Food prices are out of control. My family (2 adults + 1 toddler) are all vegetarians. We spend about 450-600 a month on food. The cost of produce has steadily gone up. We do not shop at Wholefoods either but it does seem like all of our money is going towards food. We would definitely be food insecure If there were not a few grocery discount outlets and large bulk foreign (Mexican and Korean immigrants) markets with in 30-45 minutes of my house. And I also tend to 288 sqft of raised beds and 30 gallon containers of potatoes (failed this year only ~10 pounds instead of 25-30 per container.

I do not know how meat eaters can get by unless they just skip vegetables, fruits and grains. Unless of course they are using Credit Cards to pay for essentials.

The costs of clothes have risen as well. It used to be that online organic retailers were way too much even with a good sale but the cost of clothes at the cheap places are not so cheap anymore.

Increases in pet food is also clear. Grain free pet food was about the same price as grain based diets. The increase in feed costs must have trickled through since grain free dog food that was 50-55 is not 65-75+.

Related: The lowest quintile of Americans with infants spend 13.9% of their income on diapers alone.

It maybe numbers aren’t what they used to be.

Is 3 still worth 3, or is it maybe now only 2.7 or 2.6?

How about 7, That’s a high number for any productivity measure, but it may be all the equations use 7 — even in the 10ths or 100ths decimal place — so many times that even if 7 is almost 7, say it’s only 6.8, it compounds. That might cut 2 or 3 off any final result.

Even the % sign might have some erosion in it. Maybe a % is now only 0.95%. That might have an impact, considering how much it’s used. It can get used 13 or 15 times a page! With 10 pages, that’s 150 times. At a 0.05% loss per time, that’s more than 5%.

I”ve never seen anyone think of these possibilities.

I really think that’s it. If you have disemployment and productivity (output per worker) falling, that means you are in a depression. I think they’ve been cooking their stats so long the numbers melted and ran together.

Plus, if finance and the military become a outsized proportion of the economy, what is the economic value of it all anyway?

Also too, DuPont and Dow Chemical are doing a merger. Economists will be stumped next year too!

‘financial taffy’

we might need new numbers. a “new 1”, “new 2”, “new 3”, etc.

you’d want to start over and not try to peg them somehow to the old numbers.

It’s like getting out of a bad relationship. It takes awhile before you can think of it fondly with the sentimental golden glow of memory as a poignant process of spiritual growth.

but we’d have to be prepared for a bucket of cold water! it might be productivity was below zero, really.

“neo 1”, “neo 2”….

Dude, that’s it!

I think we’ve answered the question better than any of the Big Boys in the post. hahah

“Mr. Anderson”………we appear to have a problem!”

Stop it, guys! It’s not funny anymore. (Actually it is, it’s just too depressing as well.)

Have you ever bought clothes for a woman? Where this years 6 is last years 8 which was the previous years 10. No one ever gains weight.

You are certainly on to something, and maybe something big – there’s a pervasive, universal slippage in our constructs only those old enough to recognize it and still young enough to maintain a grasp of it can sense, can almost feel – the barest perceptible something of a force chipping away at all of our important ideas. How long before a 7 is tossed out of numbers altogether?

The article assumes all these mechanical/electrical software things work perfectly and enhance productivty. It assumes your cell phone “choices” are wonderful choices for you, while they really are profit maximizing choices for the provider – which does not always equate with enhanced utility. When I was working, computer and related “technological improvements” were a tremendous time suck, and often times resulted in a less reliable output that addressed less aspects of the job. Its like a multiple choice test – it can never list ALL the possible correct answers, or even plausible answers. It often forces less than OPTIMAL answers…

In the definition of “productivity” I would assume the price of the good, for example airfare above, is what is used to calculate “productivity” Now my anecdotal experience may not be indicative of anything, but it seems to me airfares should be plunging with all these fewer employees, and lower oil prices – but that is not my experience. And again, economists leave out to what the average person considers a very important criterion – you pay the same/or more for the amount of space that would be considered cruel if it housed a sardine….

=======

“Larry Summers writes that it’s really hard to square the view that the “new economy is producing substantial dis-employment” with the view that “productivity growth is slowing”. The fact that you move through an airport with much less contact with ticket takers, the fact that you can carry on all kinds of transactions with your cellphone, the fact that you can check out of an increasing number of stores without human contact, the fact that robots are increasingly present in manufacturing, make a fairly compelling case that the increasing dis-employment we see is related to technical change. And yet, if technical change is a major source of dis-employment, it is hard to see how it could be a major source of dis-employment without also being a major source of productivity improvement.”

========

OK, I know everybody must be tired of me ranting and raving about tomatoes. So no comment on tomatoes.

So here is something else. Years ago, getting disconnected from my telephone land line took about 90 seconds. No fuss no muss. When I just recently moved, it was a half day project. After going through interminable phone trees, and choices that were irrelevant and impossible with regard to my circumstances (no phone line from ATT was available to where I was moving) – – when I finally, finally got the live person, the connection always was lost when I actually tried to get service discontinued INSTEAD of transferred or even added on to.

Only a moron would not understand that these people are “incented” to only increase service and undoubtedly are penalized if they don’t sell more product, so they just hang up on anyone trying to not use the product. I am retired, but for any person with a job, it would take a BIG BITE out of your work day trying to do something that should take seconds into something that takes hours – finding a live representative that does not hang up on you (the vaunted technology never considered that people could move and not want or be able to transfer ATT phone service)

My view is that this is happening all the time. Sure, SOME things have gotten better. SOME things have also gotten much, much WORSE…

So again, it seems to me the there are three possibilities

1. Less labor (lower quantity, lower price, and/or both) for product of comparable or increased quality – therefore productivity increases

2. technological improvement for product of comparable or increased quality – therefore productivity increases

3. Less labor (lower quantity, lower price, and/or both) for product of LESSOR or DECREASED quality – therefore productivity decreases.

The fact that number 3 is not even addressed says something about the intellectual honesty of economists or maybe they are not as smart as they think they are…

Having to do something over a very expensive smart phone is not always an improvement of doing it with a life human for free.

Expanding on #3:

Crapification of goods and services is a large, real and unmeasured problem. In my own case ~20% of goods and services purchased over the last decade, during the rise of Amazon and the hollowing out of traditional person to person market exchanges, end up broken, non-functional, and returned for a refund.

Well said. I was pretty surprised how deeply engrained that assumption was in this article. Rather than enhancing productivity, a significant chunk of activity in the US economy is designed to enhance looting or at least designed without the end user in mind. Take that very first example of airports. Flying has become more obnoxious in many places despite technology improvements due to things like TSA security procedures and the hub model reducing direct flights out of secondary airports. I have flown through Denver to get from Minneapolis to KC and through Dallas to get from St Louis to Miami. Talk about inefficient, both in time and environmental impact.

And at any rate, it’s not that wages have disappeared. Rather, wages have been redistributed upward. The inherent jockeying for a cushy job in the top 20% or so of the workforce creates a lot of activity that produces no usable output.

Merriam Webster sort of says it all:

“dis” a transitive verb slang 1: to treat with disrespect or contempt : insult 2 slang : to find fault with.

Isn’t Larry Summers, always an interesting read? David Brooks once gushed, something to the effect that he “has the extraordinary gift of ‘meta-cognition’”. I don’t know WTF that means, other than maybe DB not knowing what he doesn’t know, but I see that LS can rationalize and preach his wonky wonk obsession with making more for less so the less can have more and the more can have less, without considering that maybe distribution might be the problem and not so much productivity…how can the wonky wonkishness justify, that previous contributors to “gains” in productivity be compensated with lowered wages, under/un/mis/dis-employment or unceremoniously outcast?

…all this “meta-cognition” despite the overwhelming evidence that eventually “reaping season” is over, and should be followed by the “season” of restoration, reflection and preparation for the approaching “sowing season”, which precedes ‘growth’ in a less abstract sense, then followed by a new “reaping season”. Each cycle, with effective “reflection” could make “us” a better and more vibrant society…this might require concluding that greed is no longer acceptable, tolerable and should be the ones outcast.

I’ve always thought Larry Summers must see himself as the Gore Vidal of economics. Apparently David Brookes sees him that way too.

If you read all of what Summers writes, he says that we’ve underestimated productivity and therefore GDP as well. In turn, that means we’ve overestimated inflation, and so real wages and incomes and interest rates are higher than we think. No more wage stagnation!

But then he argues the economy is weaker than we think, and argues against the Fed raising rates– an extension of his secular stagnation theory. He closes with his research suggesting that recessions lead to permanently lower potential GDP.

So which is it, Mr. Summers, are we underestimating growth and incomes, or are we stuck in stagnation?

Hours ‘worked’ increases but the output is the same, the era of the make believe jobs are apparently here…

I suppose that it keeps people from having something as dangerous as free time: time they’d get to choose themselves what they wanted to do. Keeps people from having the time to evaluate politicians, politics or even evaluate the quality of food and or even life itself.

Let us all praise supervised work as the thing to strive for or? ;-)

Yep. It’s not exactly rocket science.

amen, bs jobs.

Of course I’ve often thought there is even more to it. Who works some of the longest hours in the world with the least vacation time and other time off? US-ians of course. It keeps them from questioning … The (U.S.) Empire. They are in the belly of the beast that runs the world afterall, and have the most *theoretical* power to do something about it, this being *allegedly* a democracy. All the more reason they should not question anything.

There is no productivity slowdown. You got it ass backwards. Productivity boomed in the 90’s and has been consistently elevated since then. Just because the rate of growth slowed down, doesn’t mean what you think.

One comment, only a little “off-topic.”

How often does craazyman have conversations with himself? LOL

He even answers his own questions posed. One could ponder are they really questions if they are already answered.

to perpetualWAR above : Answer…levity& humor…..sometimes the ice needs to be broken now and then,….to preserve everyones’ sanity..ok?

You have noticed, I assme, that there is a craazyman and a craazyboy? They often tag-team.

Sector share changes cannot be overlooked. E.G. rise of construction’s share of the productivity pie drags the aggregate down and is (comparatively) unaffected by tech changes that have taken place.

Economics has always been a “puzzle” to Larry Summers.

He is one of the reasons we are in the “craphole” economy we are in now….resultant of globalization, continuing automation, and a system of structured banking laws not enforced and subservient to that sector of our economy.

Bury this guy and his ideas….

To: polecat

I hope you realize that craazyman had me entirely entertained! Yes, sanity and levity are needed in this craazy mixed up world.

Today’s experience of inflation is class-differentiated. The things that rising in price constitute a bigger share of expenditure for those with low incomes, than for those with high incomes. That’s why upper class are so clueless about today’s inflation issue.

As for tech and productivity, most of today’s infotech is just making it cheap and easy to add more bureaucracy and more micro-management to everything. That’s not productivity-enhancing.

Re And yet, if technical change is a major source of dis-employment, it is hard to see how it could be a major source of dis-employment without also being a major source of productivity improvement.

I’ve never been a big consumer at McDonalds, perhaps going once a fortnight for something quick and consistent – usually a cheeseburger.

The stores have certainly changed the way they operate over the years. When I first went into one in 1977, and for many years after, the food offerings were all there behind the, mainly, young teenagers under hot lights, with a time system to ensure that food that had been waiting for a customer for too long was not sold.

If it was busy and you didn’t want to wait, you checked out what burgers were available and switched to a Quarter instead of a Big Mac (if you couldn’t see one (they all had different colored foam boxes)).

Service speed and the consistency of what you ate throughout Australia, were hallmark points of difference and made lots of money for the company and its franchisees. Indeed, I remember a period when, if your order wasn’t delivered within 60 seconds of you paying, then it would be free. This required people to service customers.

Today’s Maccas is very different from that time in the 70s and 80s.

After a recent couple of visits to the place, I am not sure that I want to patronize McDonalds again, or at least not regularly.

Over the last 12 months or so, the company has been replacing those front line customer service people with a touch screen – ‘so that you can customize your order and make it “your way” ‘

These are devices to replace people, and make the company more money over time, assuming of course that demand remains constant.

A recent late morning hunger attack saw me at a newer store in the suburbs of my town. I bypassed the machine and waited at the counter. I saw five people assembling burgers and fulfilling orders, but it wasn’t that busy. After 5 minutes, someone finally came over and took my order. I asked for a cheeseburger and then winced when the duty manager asked if I would like fries or a drink with that.

This isn’t the first time something like this has happened.

I feel sure that I am being persuaded to order and pay through the machine. I like talking to people, so that ain’t gonna happen.

We’re not that stupid, dontyaknow?

I already avoid Woolworths as much as I can, due to the low numbers of check outs with people, even though I pay more elsewhere. I hate using those scanners as it is so impersonal, and I’m not being paid to do it.

No wonder McDonalds is closing stores and ‘consolidating’

These corporations operate without ethics and I am dismayed to see that we continue to allow them to operate in our communities, when they see local employment as a cost rather than an asset to distinguish yourself from competitors. Corporate, social responsibility or whatever? Don’t make me laugh.

Similar experiences anyone?

In what world do price indices overstate inflation? We are living in a multi-decade stagflationary context with specific financial bailouts in the trillions of dollars. Prices are significantly higher than they would be without these public policies. We can debate whether that is good or bad that we have so many specialist doctors and McMansions, but no one can legitimately deny the cost of quality healthcare, decent housing, nutritious food, academic degrees, stock certificates, and so forth. A century ago we had passenger rail systems in our nation’s cities. Today it’s so expensive we are told we can’t even afford even the most basic of subway and light rail coverage. A century ago we had very little in the way of standing military expenses. Today we spend something like a trillion dollars a year on the national security state. A century ago a gold coin was worth $20. Today it is worth $1,000.

Good question re military, especially when it periodically just ‘loses’ $trillions down the couch.

Perhaps it is really very simple.

If you are in the Gobi desert, water is very precious and you are careful not to waste it. At the base of Niagara falls, water is very common and nobody cares if a water tank has a leak.

Productivity does not cause high wages: high wages cause productivity, as businesses work to make more effective use of a precious resource. If there is a vast oversupply of labor, due to some combination of immigration, outsourcing, and fiscal policy that boosts parasitic finance while starving main street of demand, then there will be a lot of un- and dis-employed workers, and wages will be low, and employers won’t need to worry so much about making efficient use of all that cheap labor. So more unemployed and lower productivity growth makes total and perfect sense.

I read recently that Facebook and other large tech firms are moving to an open-office system for many programmers even though it has been shown to cut productivity. But if you can get desperate foreign tech workers as indentured servants on H1B visas, this could be totally rational: as labor costs fall, the amount you would lose in labor productivity could be more than offset by the amount you save in investing less in building and maintaining nice offices.

One of the keys for me is want Larry Summers has tentatively decided is wrong, namely that Technologies take a long time to show up in productivity and that’s because it takes a lot of people and it takes a lot of work to install the technologies. While I think the effort required to implement technology is under estimated not all technologies show up in productivity at all. Many firms are in constant race to improve service through technology. In addition product refreshment needs to be done on ever shorter time scales driven by much more aggressive marketing techniques. To be fair I think Larry sort of gets it when he talks about the move from tangible manufactured goods to intangible services and he has a fair point when he suggests that no major central banker in the world, is seriously engaged with productivity growth and inequalities.

The Jan Hatzius and Kris Dawsey piece seem to argue that GDP is under measured and I think I am inclined to agree with the Forbes comment at the end. Technological change does not automatically convert to improved productivity when what the change amounts to is a different way of accomplishing the same outcome. Replacing high value-added personnel with low value-added personnel with the aid of technology skews GDP towards capital. There is also the problem that a lot of service improvements or product improvements are not aimed at the consumer but other firms. Mix in the undermining of employment rights we could be heading for a world where people have to fund their own processing power in order to get a job and you can either afford the technology to be free or are a slave to someone who can.

There are a few things missing from the discussions in my point of view. Firstly increasing and changing legislation and perhaps the biggest contributor is the role of Finance where I see GDP looking very different if you take finance and capital out of the equation. Equally there is mis allocation of capital heading for unproductive endeavors. Lastly management consultancies have been active changing management style so that it is short term target focused and less strategic with the result that you get lots of rework and failed initiatives.

I could have thrown in lack of infrastructure investment , short term employment and dis loyalty of staff, availability of low wage staff, not measuring part time work productivity correctly. My final thought is anecdotal evidence from New Zealand where the service economy plays a large part, that some 40-60 percent of staff’s time is spent on follow-up tasks, regardless of whether they are triggered internally or externally due to inappropriately used technology.Service organizations are productive when they create customer value. Anyway enough of my blather and missing the point.

I am inclined to view this as another opportunity for power and money to re-define, and then revise upwards, the Grades received for the economy, and therefore, for the efficacy of QE or something similar. Save the Fed further meddling from mortals and the Dems ‘economic record’ for the election.

The combination of technological change, de-regulation, still-growing corporate power and globalization has just hammered the daylights out of everyone who hasn’t fit the needs of the ‘new economy’ of the 21st century – which turns out to be an enormous number of people globally and domestically once it becomes evident the ‘new economy’ is very highly skewed in favour of those whose skills built it over the last 20 years, as the Internet and associated communications, including financial, combined with computing power constitutes what is critical to the ‘new economy’, and that is global-to-local size, scale, speed, connectedness, etc. A very great deal of what goes on is aimed at entertaining, amusing, spending time, wasting it.

It often strikes me there’s now a much bigger disconnect between the world Summers lives in and our own – on one level he is an academic economist puzzled as to why some numbers don’t match up the way they usually do, so, to borrow an expression, starts breathin’ through his backside’ to produce the needed arguments to account for it. I wonder how much this could play into TPP and TTIP with respect to intellectual property, etc., Patented life forms protcols, etc.

We need to return significant numbers of people back to the land using the old non-toxic methods of working soils and organics, and in forestry, getting rid of those gigantic pincers that eat trees and generally destroy the forests wherever the roads head into the bush.

The productivity paradox:

1) CEO’s receive productivity bonuses

2) Productivity doesn’t rise

The West has chosen to specialise in the service sector where raising productivity has always been notoriously difficult.

China is talking about the first fully automated factories, but things are not so easy in the service sector.

When are the first robot accountants, dentists, lawyers and hairdressers coming off the production line?

How can you have less people running any branch of Subway or KFC?

Most shops now run on the absolute minimum of staff, there can be no further cuts.

Consumer convenience has pushed up costs for supermarkets where once the consumer did the work in travelling to the supermarket, now the supermarket does the picking, packing and delivery at below cost.

The internet never raised profits and allows instant cost comparison of all products driving down profits and margins.

Amazon has dominated internet retail by cutting prices to such a level it makes no profit though its CEO has made a fortune.

Why did the West choose to specialise in the service sector?