By Claudio Borio, Head of the Monetary and Economic Department, Bank for International Settlements; Piti Disyatat, Director of Research, Bank of Thailand; and Anna Zabai Economist, Bank for International Settlements. Originally published at VoxEU

Seven years on from the great financial crisis and despite central banks being seen by many as ‘the only game in town’, there has been a renewed push for monetary policy to experiment even further. One of the latest proposals is the revival of Milton Friedman’s ‘helicopter money’. But have all the implications of what many see as central banks’ ‘nuclear option’ been fully appreciated? This column argues that this is not the case. Realising the benefits that its proponents claim exist would require giving up on interest rate policy forever.

As central banks have been testing the limits of unconventional monetary policies, many observers have started to consider more radical options. One that has been gaining ground is that of ‘helicopter money’ (Friedman 1969) or, more soberly described, ‘overt money finance’ of government deficits (Turner 2015). Proponents see it as a sure-fire way to boost nominal spending by harnessing central banks’ most primitive power: their unique ability to create non-interest bearing money at will and at negligible costs. But does this really represent an additional tool for monetary policy or is it simply a reformulation of what central banks have done so far, albeit with greater fanfare?

Helicopter Money: A Neglected Trade-Off

There is broad agreement that helicopter money is best regarded as an increase in economic agents’ nominal purchasing power in the form of a permanent addition to their money balances. Functionally, this is equivalent to an increase in the government deficit financed by a corresponding permanent increase in non-interest bearing central bank liabilities. Thus, on the financing side, the main difference with central bank asset purchases financed by issuing non-interest bearing bank reserves practised in the past, notably by the Bank of Japan during the early to mid-2000s, is that it is intended and perceived to be a permanent rather than a reversible operation (e.g. Reichlin et al. 2013). The central bank credibly commits never to withdraw the increase in reserves.

There is also general agreement that how the nominal expansion will be split between increases in the price level and in output depends on the broader features of the economy, notably how much prices adjust (‘nominal rigidities’). But, regardless of the split, in the models typically used, permanent monetary financing boosts nominal demand more than temporary monetary financing because it relaxes the (consolidated) government sector intertemporal budget constraint (Buiter 2014). Less debt finance means lower interest payments, forever. Even if the government issued debt, if this was purchased by the central bank which, in turn, issued non-interest bearing bank reserves, the consolidated government sector would incur a lower interest debt service burden. All else equal, this saving would boost nominal demand, as there would be no need to raise additional taxes.

But this argument misses a crucial trade-off. Given the intrinsic features of how interest rates are determined in the market for bank reserves (bank deposits at the central bank), the central bank faces a catch-22. Either helicopter money results in interest rates permanently at zero – an unpalatable outcome to most, including those that advocate monetary financing1 – or else it is equivalent to either debt or to tax-financed government deficits, in which case it would not yield the desired additional expansionary effects.

Just a Little Matter of Monetary Policy Implementation…

The reasoning is simple. Banks hold reserves for two main reasons: i) to meet any reserve requirement; and ii) to provide a cushion against uncertainty related to payments flows. The amount of reserves demanded in excess of the reserve requirement is then very interest-inelastic (i.e. in effect, vertical), dictated largely by structural characteristics of the payments system, which effectively do away with end-of-day settlement uncertainty.2 In monetary frameworks focused on setting targets for a short-term interest rate, what is critical for achieving these targets is how excess reserves – i.e. holdings over and above any minimum requirements – are remunerated. This is what determines the overnight rate.

There are two types of remuneration schemes.

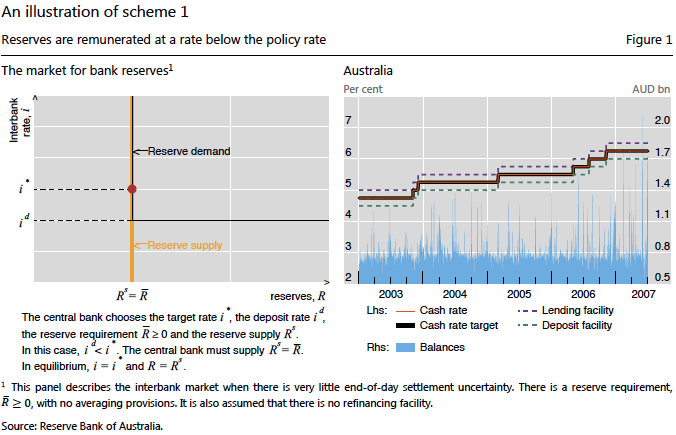

Figure 1

In one type, excess reserves are remunerated at a rate below the policy rate (Figure 1, left-hand panel) – the most common scheme. In this case, achieving the desired interest rate target requires that the central bank fine-tunes the amount of reserves to meet the interest-insensitive demand (Rmin), which is typically a small, frictional amount. Failure to do so would generate significant volatility in the overnight interest rate. Any excess would drive it to the floor set by the remuneration on excess reserves (zero or the rate on any standing deposit facility), as banks seek to get rid of unwanted balances by lending in the overnight interbank market. Any shortfall would lead to potential settlement difficulties, driving the rate to unacceptably high levels or to the ceiling set by end-of-day lending facilities. The Reserve Bank of Australia, for example, operates such a scheme, with no reserve requirement. Note the small and stable amount of excess reserves, spikes aside (right-hand panel of Figure 1). The central bank then sets the rate wherever it wishes, by signalling and/or operating at that rate.

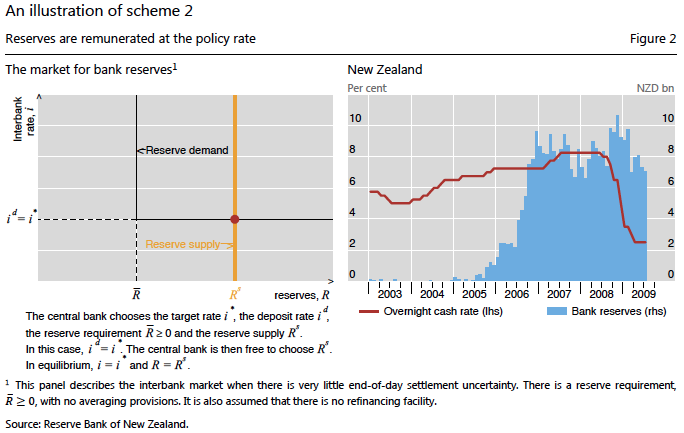

In the alternative scheme, the central bank remunerates excess reserves at the policy rate – typically the deposit facility rate (Figure 2, left-hand panel). It then supplies more balances than necessary for settlement purposes so as to operate on the horizontal portion of the demand for bank reserves. This sets banks’ opportunity cost of holding reserves to zero, as they become a very close substitute for other short-term liquid assets. The central bank can then supply as much as it likes at that rate. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand represents a good example, having moved in 2006 to such a framework (right-hand panel of Figure 2), after having hitherto operated as in scheme 1. Many major central banks, including the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, have been operating under such a scheme post-crisis.

Figure 2

In either case, interest rates can be set quite independently of the amount of reserves in the system. A given quantity of reserves is consistent with many different levels of interest rates; conversely, the same interest rate obtains with different amounts of reserves. The ‘decoupling’ of interest rates from reserves is obviously well known to central banks but, surprisingly, it has not yet found its way into textbooks and economic thinking more generally. It is discussed in detail in Borio and Disyatat 2010, Disyatat 2008, Borio 1997 and Keister et al. 2008.

…That Cannot Just Be Ignored

This seemingly innocuous technical detail has major implications. The central bank can of course implement a permanent injection of non-interest bearing reserves and accept a zero interest rate forever (scheme 1). This produces the envisaged budgetary savings but at the cost of giving up completely on monetary policy. If the central bank wishes to avoid that outcome, it has only two options.3 It can pay interest on reserves at the policy rate (scheme 2), but then this is equivalent to debt-financing from the perspective of the consolidated public sector balance sheet – there are no interest savings.4 Or else the central bank can impose a non-interest bearing compulsory reserve requirement equivalent to the amount of the monetary expansion (so that excess reserves remain unchanged – scheme 1), but then this is equivalent to tax-financing – someone in the private sector must bear the cost.5 Either way, the additional boost to demand relative to permanent monetary financing will not materialise.

The models fail to bring this crucial point out because they omit a realistic determination of the nominal interest rate. Typically, they neglect bank reserves altogether on the presumption that there exists a traditional money demand function that relates interest rates to the money supply (cash), the price level and income. For a given level of the interest rate, this relationship dictates that an exogenous rise in the money supply will lead to a proportionate increase in nominal income (with flexible prices, just in the price level). In fact, such models often imply that monetary financing will increase nominal interest rates (Galí 2014).

As we have made clear, in the market for bank reserves where interest rates are actually determined, there is no such thing as a well-behaved downward-sloping money demand function. Unless interest is paid on excess reserves, the central bank must supply the specific amount of reserves banks demand – no more and no less. Moreover, cash does not influence the setting of the interest rate. In real life, central banks meet entirely passively the public’s demand for cash (e.g. Grenville 2013). If they did not, either the amount in excess of desired balances would be converted into bank deposits and then switched by banks into excess reserves, or it would fall short of the demand, frustrating the public, which would presumably turn to alternative means of payment.

Beware of Central Banks Bearing Gifts

Helicopter money, as typically envisioned, comes with a heavy price: it means giving up on monetary policy forever. Once the models are complemented with a realistic interest-rate setting mechanism, a money-financed fiscal programme becomes more expansionary than a debt-financed programme only if the central banks credibly commits to setting policy at zero once and for all. Short of this, these models would suggest a rather limited additional expansionary impact of monetary financing.

If something looks too good to be true, it is. There is no such thing as a free lunch.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Bank for International Settlements or the Bank of Thailand.

See original post for references

Whats this, the reverse Ricardian equivalence via different words?

Nothing new under the sun, really. As Mosler and I don’t remember who wrote a long time ago, ‘the natural rate of interest is zero’.

I could be wrong, but I think there is a sleight-of-hand in this paper. The authors acknowledge that the CB can create money at will (helicopter money), but then argue that to keep controlling the interest rate, it would need to pay interest on excess reserves, which would be ‘equivalent to debt-financing from the perspective of the consolidated public sector balance sheet’. But in practice, if the CB can create money at will, and if the CB is paying interests instead of the Treasury, then the problem vanishes. The term ‘consolidated public sector’ is rather misleading here.

Sorry if I wrote something stupid.

You didn’t say anything stupid. I would use the term okee-doke as opposed to slight of hand, because retail prosperity is anathema to the neoliberal agenda of debt-peddling contraction. The banksters are imposing another QE hustle with which the public believes The Fed is proposing easy policy for organic growth.

Beyond keystroking infinite scrip, the banksters can pipeline trillions via the ESB. Although unremarked, I will put the stupid bullseye on myself by saying the Treasury was privatized in 1913.

Just shows that our vocabulary is meaningless as the terms public and private are muddled these days as the people who run the government get swung through revolving doors of influence. I believe the U. S. Treasury is and always has been part of the ‘public sector.’ Public being that term as defined by Macmillan online

sector being defined

The Federal Reserve says this about its board of governors.

And the Treasury does operate independently of the Federal Reserve although there is a Byzantine connection.

Yes, the banking industry has a heavy hand in the operation of the U. S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve; members of the upper echelon in those two bodies will have had lots of experience in the financial sector often in state governments as well. But the banking industry itself runs along very often without heavy handed direction from the government.

I’m trying to imagine a world without banks and I seem to remember Randy Wray writing about that very topic but I can’t lay my hands on what he had to say. The U. S. Treasury could have local outlets like the U. S. Post Office does and banks could be dispensed with forthwith. After all, there’s only one source for all currency within a sovereign nation. If need be the Treasury could delegate independent clearinghouses to act as conduits for the flow of debt and asset transactions. Likewise the Federal Reserve, at all levels could be shut down. This is not just an exercise in rhetoric but an actual attempt to show that we need to break free from the binding arrangements that are causing the economy to stagnate badly.

Oh no, you mean that policy that has so signally failed to serve the interests of anybody not personal employed in the financial industry? Oh boo hoo.

The obit for NAIRU right there at the bottom of the first paragraph! How can we possibly keep the poor begging in the face of such a catastrophe!

This argument basically boils down to: if we try to fix one problem with this dysfunctional economic system, it’s going to interfere with other parts of the dysfunctional system. If you try to use the governments power to help poor people, that might screw things up for the rich! Can’t have that. Best do nothing (or just what we have been doing) than risk trying something new that might have unintended consequences. The status-quo is always safer, any change (especially one expected to benefit the plebes) is a dangerous innovation. As we say among the Dothraki, “It is known.”

why try anything? Just let the system default, i mean after eight years of this crap i think this may have been the best approach: “liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real estate… it will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up from less competent people.”

One problem: the people getting “liquidated’ will be overwhelmingly those at the bottom, i.e. the people who didn’t cause this problem in the first place. The rich were long ago made whole and have been hording assets like mad for years. They are not going to go down if the system goes “tilt”. It will be millions of schmoes who live paycheck to paycheck that are going to be wiped out.

Well Mr. Levy, have you tried talking to the schmoes since 2008 about what is going on? I have and the glazed look in their eyes or the effort to shoot the messenger is pointing me after all these years towards door number 2. They just may deserve what they get. Don’t get me wrong, i believe the wise/strong/whoever should steward the less well endowed, but you try and do that and they’ll bite your head off. So instead we’ll have a slow burn where we end up at the same outcome, just at a slower more acceptable pace for some.

I think Trent may have been being sarcastic, since he was quoting one of the architects of the Great Depression, Andrew Mellon. (Though Mellon later denied saying it).

The main issue with helicopter money is insuring that it is spent rather than sitting in bank reserves. If private money is not given to the Federal Government in exchange for bonds, it will instead go into bank reserves until some other use is found for it. That is, one dollar of FR purchase of government bonds will result in one dollar additional bank reserves in this naive model.

What that implies is that the helicopter money needs to be a true helicopter drop as Milton Friedman originally described it — i.e., raining money down on deprived neighborhoods that have extensive unmet needs that will result in the money being immediately spent, rather than in the money going immediately back into bank accounts. Simply issuing money and giving it to the government results in fewer bond sales and thus less excess capitalization moving from bank reserves into the economy, which sort of defeats the purpose.

Sadly he Chicago plan is about is undemocratic as it gets and some people have issues with the Fed…

Disheveled Marsupial… Milton’s whole career was based on bailing out his benefactors come hook or crook…

Badtux wrote: “….. money being immediately spent, rather than in the money going immediately back into bank accounts”.

Your conception of “true helicopter drops” is false I think. Every new dollar created by government goes to a bank-account. Spent or not spent they will stay in someone´s bank-account. Consuming or saving is the question. The size of bankreserves is a matter of monetary policy and inflation.

I don’t understand what is being discussed in this article. When I hear the term helicopter money, I guess maybe I’m being too hopeful, I think of stimulus checks which I can use to pay off personal debt, i.e. mortgage, car and student loans and use for home maintenance or saving for retirement or use for anything else our measly household income cannot pay for.

The MMT primer (http://neweconomicperspectives.org/modern-monetary-theory-primer.html) discussion of “vertical” and “horizontal” money would be helpful. Read the whole thing as opportunity arises, and don’t rush. This is really worth understanding.

As I understand it (and better-informed readers: please correct me), the Central Bank creates (“prints”) money electronically, by changing data entries in its datafile of reserves balances credited to various institutions that have reserves accounts with the Central Bank. When the CB wants to purchase a bond from a bank, it simply credits the bank with the number of reserves that the bank agreed to sell to the bond for. CB purchases of bonds from the private entities in the financial system thus increase reserves balances, and CB sales of bonds to the private entities decrease reserves balances.

CB helicopter money directed to citizens would add $ to individual demand checking accounts held at private banks, and would credit those same banks with an equivalent amount of reserves. This is why CB helicopter money increases the levels of reserves “in the banking system” (ie, in the reserves accounts of the banks at the CB). When these exceed the level needed for nightly payments settlement, it drives the overnight interbank rate to zero (regardless of what the CB would like, in its policy stance, the overnight rate to be) as banks compete with each other lend their excess reserves to each other in an attempt to earn a little interest on them.

I think something similar happens if the helicopter money comes from the Treasury instead of the CB, but I’m not clear on the operational details.

From reading it, I gather (correctly, I hope):

1. When the CB buys bonds from banks, it creates competition among banks to lend reserves to each other.

2. When the CB helicopter drop money to citizens, it again creates competition among banks to lend reserves to each other.

They seem the same.

Every night, the banks try to lend their excess reserves to other banks in order to generate additional interest income. Too many reserves creates a surplus with respect to what is needed by the system as a whole to settle payments each night.

in terms of the effect on overnight rates, yes: excess reserves in the CB accounts of the private banks — regardless of the reason that they are there — will drive the overnight interbank lending rate some floor; in my first comment, I took the floor to be zero.. As other commenter(s) have noted, recently the US Fed has been paying the banks interest on excess reserves, which provides a floor to the rate a bank would accept to lend its reserves to another bank (to settle payments). In a more “normal” policy regime, the CB might not pay interest on excess reserves, in which case the floor on the overnight interbank market would be zero.

===

In the case of a Treasury helicopter drop (Treasury mails checks to households), I think it must be the case that if Congress were to authorize Treasury to create additional money, the CB would accommodate that by creating a corresponding amount of reserves in the Treasury’s reserves account at the CB. In practice, the Bureau of Engraving would not actually print paper money; the CB would simply create the reserves in the Treasury’s reserves account, and when the Treasury checks mailed to households were deposited, those payments would be made from the Treasury’s reserves account to the respective private banks’ reserves accounts. So it works out basically exactly the same as a direct helicopter drop by the CB into individual citizens’ bank accounts.

And this helps me to understand the remarks made a couple of years ago that the Fed would not honor a “Trillion Dollar Coin” if such a thing were minted by the Treasury department (pursuant to an obscure provision of a 1990s era law authorizing Treasury to mint platinum coins in denominations decided by the Secretary of the Treasury). Evidently, they would not be willing to credit the Treasury’s reserves account with the face value of such a coin were it to be presented to the Fed for deposit.

How would a helicopter-drop from the FED work in reality? A centralbank can “create money” when they buy i.e bonds in a market. Still this “newly created money” is debt to the Treasury neutralized by it´s bond-holdings(incl interest). Monetization is NOT money-creation! How then can FED drop newly created money on every citizens bank-account? Well of cource this is the job of the Treasury, not the FED. FED is just making a bookentry of the transactions. The FED is the Treasury´s bank.

New financial assets(debt free) can ONLY be created by the government. Monetization of G-bonds is only a swap of currency(cash).

I’m not sure that it’s precisely right to say that excess reserves “creates competition” between banks in the overnight interbank lending market. The market is there and the banks are already “competing” in the sense that banks with excess reserves hope to get as much interest as possible by lending them, and banks that are deficient in reserves hope to borrow them at the lowest possible cost. So the market is already there and would-be borrowers and would-be lenders are negotiating interest rates at which they are willing, respectively, to borrow and lend. There must be some kind of electronic system for matching bids and offers. But if there are too many reserves, there will be more offers than bids and a race to the bottom, in the would-be lenders’ hope of getting something, anything, in terms of a little additional income out of their excess reserves, will drive the overnight rate down to the floor of whatever the CB is currently paying banks for their excess reserves.

( one can envision the opposite situation, in which there are too few reserves and the overnight rate is bid up above the CB’s target rate by banks desperate to find reserves to settle payments. The CB endeavors to keep the actual “demand/supply” equilibrium price close to its target by regulating the level of reserves through sale/purchase of assets to/from the banks in order to withdraw/inject reserves. I don’t know a lot about this but I have the impression that they are so good at this that the bid/offer in the interbank market rarely strays from the Fed Funds rate target. But in the case of a helicopter drop big enough to have macroeconomic consequences, large quantities of reserves are added and, as described in the piece, the overnight rate plummets to zero or to the support level that the CB has set if it pays interest on excess reserves.

How did this tripe get on NC?!?!? His garbage findings stem from the heart of his failed mainstream economic modeling which assumes a government budget constraint which is nonsensical for a government which spends in its own currency which freely floats on the forex market. And he gets an F for accounting. Monetary policy means that the non-government sector only swaps a financial asset with the central bank and its total net financial asset holding remains unchanged. “Helicopter money” means the net holdings of financial assets held by the non-government sector goes up. That’s where your expansionary impact comes from.

I think this was one of those piñatas that our hosts put up from time to time to test our skills at dissecting bad arguments.

Yep.

Money only has the significance that we humans allow it to possess. Imagine if, one day, all manifestations of what we now call “money” were to disappear. Paper and metal currency burnt and melted down. Electronic records of account balances, debts and credits wiped out through some irreparable, systemic eradication. Titles, deeds, stocks and bonds– gone forever.

What would be left? The physical world, as it exists, this very moment. Trees, plants, and rivers. Buildings, roads, automobiles. Docks, ships, airplanes.

No way to prove who “owns” anything. No more buying, selling or renting stuff. Could we manage that? Could humans get together– and work out a way to meet everyone’s needs through the sustainable stewardship of resources common to all?

Would chaos, murder and mayhem break out? Or, would people get to work cleaning up current messes and organizing to ensure a sustainable, happy future for everyone?

The gods of business as usual have failed. Who do we turn to now, as we stand on the edge of making the only planet we have inhospitable to human life?

Except, it’s the only way to pay taxes. And thus required to avoid jail.

His argument is either incoherent, or over my head. IIRC, the Fed currently pays 0.25% on reserves. If the reserves are huge, then this may be a large number, but it would still be way below the gains a bank could make lending the money. Hence, even though reserves are necessary for system resilience, the interest earned on reserves is likely a fairly small concern to banks, and fairly meaningless to the CB. I assume the Fed earns many times its reserve costs through its various lending windows. Should we expect Randy Wray to debunk this?

I think the author was making a very narrow point, that helicopter money drives the interbank overnight rate to zero (or to whatever floor the CB sets through payment of interest on excess reserves).

That point is true and, as Scott Fullwiler noted, was established by MM-theorist economists in the ’90s.

The author of the piece thinks this is terrible, since it deprives the central bank of its standard monetary policy tool.

Skeptical commenters are scratching our heads, since we reckon that fiscal stimulus (which is what a helicopter drop would amount to) has to be more useful than monetary policy that is already at the zero lower bound.

I would like to see consideration of other forms of stimulative unconventional monetary policy, such as CB purchase of infrastructure bonds.

When an economy is running well below capacity, there really can be free lunches.

Isn’t LIBOR highly manipulable? Seems like setting it at a floor beats “let the market decide..”

That was my reaction as well – a pinata article for sure. The author seems to miss the point that the main benefit of helicopter money would be to a) give money to people who need it and will spend it while b) not freaking out the ZOMG look at the public debt austerity now crowd (i.e. all of the MSM)

Also, that the point is not for the lunch to be free (although it will be where the ZOMG crowd above enforces unnecessary austerity), but that the lunch will be paid for by the money hoarders – which perhaps gets to the source of this article.

All money is not equivalent, because it depends on whose hands the money is placed.

If the poor it will be spend on the bottom two or three levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs, food, shelter and families. If the rich on the top two esteem and self actualization – accumulation, rent extraction, trophies and toys for the rich.

What the author does not discuss is how money produced by the central bank is spent, and by which segment of society.

Giving money to Banks only increases debt. The interest payments on the money created further stifle the economy, and transfer more money to the top tiers of Maslow’s Hierarchy.

Agree strongly. It’s not just the “what”, it’s the “where”.

Specifically: It’s the distribution, stupid.

Giving up on artificial signals reinforcing global poverty with feudal RE inflation and right to bankruptcy would be a good thing. Helicopter money can’t work because the special interests are not going to give their “equal rights” in trade for processing the debt slaves.

America is an empire, depending upon global slave labor to do what most Americans have neither the interest nor capability to do. The idea that foreign bases can simply be shut down and resources shifted is nonsense. The Austrian machine was moved here during WWII, and the subsequent move to China failed.

You have an input funnel and an output funnel, with Wall Street at the base. Wall Street blew up again and a younger set is morphing it. Wall Street takes a cut, “wealth” trickles, part of the output is returned to input, and most is lost to friction with nature, because it’s a Fred Flintstone operation, with expert misdirection posing as intelligence.

Beware of central bankers telling you there is no free lunch, and using a lot of Central Bank gobbledygook economics – about reserves – to prove it.

It is easy enough to determine empirically. Let the government commit to some helicopter money, either

(a) to finance and build assets determined useful by the government, or

(b) to hand out to individuals for a determined amount of time,

and see if it really means that there is no way the Central Bank can set interest rates, should there be some inflation.

That is really all Central Banks are supposed to do with their independence. Set the level of interest rates to avoid inflation. (Whatever happens to reserves is really of secondary concern!)

I think we will all find that there is a free lunch!

Yes that ‘no free lunch’ bit seemed a little disingenuous. IIRC the Fed’s ZIRP allowed large banks to borrow funds at 0% which they then turned around and used to purchase interest bearing treasuries.

Nice work if you can get it.

We have seen from the resort to unconventional monetary policy by the US and other central banks that the overnight interbank rate isn’t the only interest rate that a central bank can target.

I think I understand the argument of this piece and I agree with it with regard to the implications for the short-term policy rate. IIRC, Randy Wray’s MMT primer makes similar points (deficit spending via Treasury money creation injects reserves and drives the overnight rate to zero unless the central bank withdraws the reserves) and in fact affirms that many MM-theorists prefer that the “safe-asset” interest rate be at or very close to zero at the short end of the yield curve.

But the fact that helicopter money pushes the interbank rate to zero does not mean that central banks lose all influence over the level and shape of the yield curve. They could, for example, use open market operations to control the yield of longer maturity government paper (or even of other assets), and could — it seems to me — in principle create any yield curve they wanted, provided that it was pegged to zero at shortest maturities.

So I think that central banks may not lose control of monetary policy, but will have to target other rates than the conventional overnight rate that has historically been the preferred tool.

Well said. There’s nothing operationally in the piece that MMT hasn’t said since the very beginning in the 1990s. You can’t print money w/o ZIRP forever. (And note yet again that there is no citation of MMT.) But that doesn’t have to mean no monetary policy–it just means you can’t use the overnight rate. The problem is neoclassical models only have that one interest rate in them, so they can’t think of what else monetary policy could do.

Miss seeing you since I went dark…

Wayward Septic… thanks for your efforts…

Always fun to read supply side economic nonsense and look for the flaws in logic – what underlying assumptions does the author use to make his case. If you have read Steve Keen it helps. Here is the line:

“but then this is equivalent to tax-financing – someone in the private sector must bear the cost.5 Either way, the additional boost to demand relative to permanent monetary financing will not materialise.”

This is a typical neoclassical assumption – that all consumers are the same and a dollar in a billionaire’s pocket does no more for demand than a dollar in an elderly retired person’s pocket. It’s the false assumption (see Steve Keen – Debunking Economics) that allowed neoclassical economics to go from the micro-economics of a “single consumer, single product” to the macro-economics of supply side modeling. These guys believe the economy is equivalent to one consumer and one product – utter nonsense. Guys like Claudio Borio drank the neoclassical koolaid and can’t see their blind spots. They don’t understand history because it doesn’t agree with their economic world view – so they deny reality. Redistribution creates demand. When only the 1% have all the money, demand goes kaput. But I guess anyone who believes the world (or the economy) is always in equilibrium – always static – will believe just about anything. To argue that demand is independent of who has the money is utter nonsense.

Of course taxing the rich and using the money to create useful jobs building infrastructure would be better than helicopter money – and far better than another bailout of the 1% which just postpones the inevitable collapse.

I provide free lunches to people all the time, in part to demonstrate that the saying “There is no such thing as a free lunch” is untrue.

If you have to work for that money, it’s not free lunch.

What work do you have to do?

You have to spend that money.

Yes, spending money is work.

As in, the government spends to stimulate the economy. Why can’t you citizens be more grateful? The government is working hard to help you.

So now we know why we can’t have nice things… at least according to BIS (not necessarily an objective institution)

Here‘s a better take on the money situation.

Helicopter money boils down to just writing a check to every citizen with a pulse, right? If so, how on earth was this a Milton Friedman idea? Creating a bunch of ‘fake money’ and giving it to people represents everything he hated.

They can regulate in Singapore but not in USA?? : http://www.sarawakreport.org/2016/05/worlds-biggest-money-laundering-investigation-goes-up-another-gear/?utm_source=Sarawak+Report&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=e01b9423d5-RSS_EMAIL_CAMPAIGN&utm_term=0_97635b3a5d-e01b9423d5-291780757

Just look at Japan. In practice they have been “dropping money” almost at zero-interest. When interest-rates are null or negative helicopter-drops or debt-free budgetdeficits can continue until inflation picks up. Then treasury have to buy back bank-reserves by issuing debt(and/or raising taxes).

Why is even helicopter drops to be considered? Too low growth! Either you kickstart the economy and inflation picks up(demand driven) or there must be structural impediments to growth. In the latter case helicopter drops is not the proper medicine even at zero rates. But you can continue. Just look at Japan(but strangely they choosed to raise VAT).

How about we quit looking at solving the micro issue “insolvency” with macro level liquidity.

Bankruptcy.

Enforcement

Let failed business models fail.

Picking on poor old Warren B … Warren didn’t have a liquidity crisis to be bailed out by Washington. He was insolvent. He was bankrupt. He should have been removed and his assets redistributed to pay the liabilities he could NOT afford to pay.

A mess? For sure. In fairness, we have a mess now, however.

When picking “the winners”, the winners don’t get to do the picking.

Our understanding of economics and the economy have always been poor, which always leads us to the current state of affairs. Eight years on from 2008 and nothing is really fixed.

Following pre-1930s ideas, the US economy crashed in 1929 and following these ideas just made things worse.

Eventually Roosevelt picked up on new thinking from Keynes and came up with a “New Deal”.

These ideas flourished in the 1950s and 1960s, but came unstuck in the 1970s and following these ideas didn’t provide a solution.

Eventually, Thatcher and Reagan came along with the next set of ideas, which worked for a couple of decades.

But once finance was finally freed from the 1930s legislation, it blew itself up again in under 10 years (2008).

We seem to be trying to hold onto the current set of failed ideas for far too long, it’s been eight years since 2008.

Helicopter money is just another desperate attempt to keep these failed ideas on the road.

New economic ideas initially offer much promise, but after a couple of decades these ideas lead you into a cul-de-sac where the only way out is to adopt new, different ideas.

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” Albert Einstein

Right again, Albert.

Where do we start looking for new ideas today?

The people that did see 2008 coming.

Steve Keen tried to warn the world about the private debt bubble inflating in 2005.

He uses realistic assumptions about money, debt and banks in the economy to produce his models that saw 2008 coming.

Today’s economics makes very simplistic assumptions about money and debt that blinded today’s economists to 2008.

Complex mathematical models built on false assumptions are of little use.

Michael Hudson goes back to economic history to re-discover the difference between “earned” and “unearned” income to see how the parasitic, rentier side of Capitalism has over-taken the productive side.

Adam Smith has it in one paragraph:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

Adam Smith saw landlords, usurers (bankers) and Government taxes as equally parasitic as they all raise the cost of doing business.

He sees the people at the top living off “unearned” income from their land and capital.

He sees the trickle up of Capitalism:

1) Those with excess capital collect rent and interest.

2) Those with insufficient capital pay rent and interest.

He differentiates between “earned” and “unearned” income.

Michael Hudson did see 2008 as being due to excess debt, the same as everyone else that saw 2008 coming.

Acknowledge the problem to find a solution.

The banker’s love their “free lunches”:

1) Unconditional Government bailouts

2) QE, worthless assets swapped for real money

3) The TBTF subsidy

The “free lunch” taboo has gone; let’s all tuck in.

Thanks for the laugh. That is funny whether it’s an MMTer claiming that high value platinum coins would be a game changer in the kabuki theater of deficit ceiling debates or a trio of comfortable economists casually referencing models that have no connection to the real world.

Budget constraints are political, not monetary. That is both empowering (yay, government can spend money), and it sucks a lot, since it means that monetary theory is completely irrelevant to the problems of our era. Everyone* is a chartalist, from warmongers to banksters to climate change deniers. The debate is who gets the spending and who pays the taxes.

*no offense, gold bugs…

Classic banker propaganda! Blind them with technical bullshit. All true perhaps in the context of a totally corrupt system favoring the rich, but very misleading in light of more sane and democratic alternatives to running a banking system. I say “bring on the helicopters….for the rest of us!!” P.S. I think “diptherio” got it right!

That’s one of the more delicious ironies of all of this when one is in the mood to chuckle at the whole thing. Even Milton Friedman was more re-distributive than our present crop of looters.

While I agree with many comments and would happily consign the private banking cartel’s abhorrent system to oblivion, I have to believe the authors’ work would not have appeared at all absent some interest within BIS in having this claim re ‘helicopter money’ floated, and especially given a good deal of discussion of such a possibility in the global business/finance/banking/business community and press. And given that community and press has long been deeply mystified, even enthralled by the Fed, my sense is that the ‘helicopter money’ discussion as a real possibility likely came swirling up the chimney from the Fed earlier this year as a way of attempting to maintain the myth of unlimited Fed prowess held in reserve.

Since the Fed doesn’t make mistakes – we have their word for it – perhaps BIS is indirectly pointing out they forgot to consider ‘helicopter money’ from a reserve currency perspective, or at least that of one currency among others? What is BIS’ policy stance re other countries’ use of ‘helicopter money’ that doesn’t involve paying banks for the privilege?

In any case, the claim is like any other relying on taking the initial set of conditions as ‘given’ when the ‘given’ is what the small fry are to the sharks.

Monetarist like M Friedman and centralbankers have tried to “take credit” for the Helicopter-money solution. That is wrong. The whole concept of helicopter-drops is of cource a matter for the Treasury, not the centralbank. A centralbank is the Treasury´s bank which is the receiver of newly created financial assets(i.e helicopter-money) paid out by the Treasury. It is an accounting-thing only, not a monetary policy-instrument. Monetary policy comes in when inflation picks up and bank reserves have to be reined in.

I think this misconception has to do with how money is created and government debt. New government money does not have to be financied by debt. Debt on the other hand is a monetary policy-question.

there is no free lunch dude ? banks creating money by lending is not free lunch here is actual proof from the bank of england : http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf arbitrage is not free lunch when investors outperform the market by 3 precent and going pass the efficient frontier is not free lunch newly created spending power money new money that boost demand in every aspect is not free lunch in your DSGE,lucas critique world there is no free lunch sure where money are neutral and banks are intermediaries where there is perfect competition and inflation is always excessive and linear mate you do understand that lender of last resort and deficit spending is the only way to get out of deflation not just waiting for foreign investors that has been highlighted by irving fischer , henry simons , hayek, keynes,knut wicksell,milton friedman,paulsamuelson everyone that understands that capitalism runs on sales oh and trying to understand bank reserves and endogenous money from equillibrium and lonable funds is a lost cause and something far from an empirical proof since even its own assumptions contradict the existance of this model seriously every inflation forecast has been wrong and every assertion that this static model has given about great moderation and that its the feds fault for the crisis because of low rates has also been wrong when jovens and marshall used this model they invisioned it to be temporary and that economics would switch to dynamics in the future even what this model considers as stability is not actual stability: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1907571?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents Excess(private debt mostly) Debt And Deflation = Depression or recession that is a fact look private debt to gdp and asset prices those are real numbers