Classical economists depicted various forms of rent-seeking, such as monopolies, cartels, and other forms of collusion, as destructive and thus needed to be constrained. This study provides more support for that long-standing view by looking at economic effects more broadly than other studies have. It also finds that intervention reduces inequality.

By Fabienne Ilzkovitz, Competition Directorate General, European Commission and Adriaan Dierx, Directorate General for Competition, European Commission. Originally published at VoxEU

Firms with greater market power can behave monopolistically, and recent research suggests that declining market competitiveness is driving income inequality. While competition authorities already measure the overall impact of their interventions by using customer savings, these measurements do not account for indirect effects of intervention. This column introduces a DSGE model to model competition policy interventions as a negative mark-up shock. Competition policy has a significant and positive impact on growth and jobs, and impacts richer and poorer households differently. Interventions have important redistributive effects that benefit the poorest in society.

Firms that have market power can charge higher prices and earn monopoly rents above competitive rates of return. But the overall impact of market power goes beyond these direct effects. In a recent article, Paul Krugman (2015) argued that market power has been rising and that this rise is driving the increase in income inequality. The corollary of this statement is that competition policy, which aims at preventing companies from abusing market power, contributes to inclusive growth. It is often argued that the poorest in society are more affected by the higher prices and lower quality and choice resulting from a lack of competition. However, the macroeconomic and distributional effects of competition policy have rarely been studied (Van Sinderen and Kemp 2008 and World Bank 2016 are two exceptions).

There is Some Evidence That Competition Policy is Beneficial to Consumers

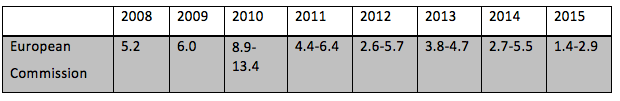

Robust evidence of the macroeconomic and distributional effects of competition policy would be extremely valuable for authorities and policymakers, especially because of increased scepticism on the benefits of competition policy. Usually, competition authorities measure the overall impact of their interventions by customer savings, which reflect the benefits of price increases avoided by major competition policy decisions. These customer savings are calculated by multiplying the lower prices – measured against the counterfactual of no competition policy intervention – by their expected duration and the turnover in the market affected by the decision. This requires assumptions1 regarding the price effect and its duration, while the turnover in the market concerned is taken from the decisions themselves. Estimates of annual customer savings resulting from important merger and cartel decisions by the European Commission range from 1.4 x10-2% to 13.4 x10-2% of GDP (see Table 1).2

Table 1 Estimates of annual customer savings (% of GDP x 10-2)

Source: Own calculations based on EU sources.

However, These Estimates Only Cover the Direct Price Effects of Competition Policy

The strength of the customer savings approach is that it is relatively easy to understand by a wider public. Moreover, the above estimates can be directly associated with important decisions taken by the European Commission. However, customer savings estimates only measure direct price effects of competition policy interventions, and do not take into account other effects such as on product quality, customer choice, product and process innovation, etc. Moreover, they do not consider the deterrent effects on competitor behaviour or broader macroeconomic effects on growth and employment. As a result, customer savings provide only a partial view of the benefits of competition policy.

Competition Policy Decisions Also Have Indirect, Deterrent and Macroeconomic Effects

Competition policy decisions have not only direct price effects but also deterrent effects. These deterrent effects discourage future anticompetitive behaviour. They appear to be affected by three factors – the likelihood that anti-competitive behaviour will be detected, the expected punishment following detection, and the ‘reputation’ of the competition authority involved.

Deterrent effects are difficult to measure as they are not immediately felt and cannot be observed directly. Most of the estimates available are based on surveys of business managers and their legal counsels. These surveys, however, have clear limitations as there is no way of checking the reliability of the information provided by respondents. Recently, methods based on statistical and economic theory have been developed to better gauge deterrent effects (Davies and Ormosi 2014, Katsoulacos et al. 2015). Nevertheless, even when applying more sophisticated methods, available estimates of the deterrent effects of merger and cartel decisions remain quite inaccurate.

The customer savings approach also fails to capture the indirect consequences of lower prices for the economy as a whole. However, it is extremely difficult to track the chain of events triggered by competition authorities’ decisions in the medium and long term and measure their macroeconomic impact.

Modeling Competition Policy Interventions as a Negative Mark-up Shock

The approach used in this column (see Dierx et al. 2016) considers that competition authorities’ decisions represent a negative mark-up shock to QUEST III, which is a Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium model developed by the Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs (Ratto et al. 2009). The QUEST III model does three things. It (i) assumes that goods markets are imperfectly competitive, (ii) disaggregates employment into different skills categories, and (iii) considers different types of income earners (capital owners, wage earners and benefit recipients).

The size of the mark-up shock is derived from microeconomic data used to calculate customer savings from major decisions taken by the European Commission, which is an innovative approach to measure the macroeconomic impact of competition policy. In the literature, the strength of competition policy is often measured by a binary variable indicating the existence of competition law or authority, the budgetary resources devoted to competition policy enforcement, or composite indexes calculated on the basis of the main characteristics of competition laws and institutions. However, no direct link has yet been made with the decisions taken by competition authorities or the markets affected by these decisions.

Taking Account of Deterrent Effects

To take into account the deterrent effects of competition authorities’ interventions, the QUEST III model simulations assume that the avoided price increase associated with merger or cartel decisions covers not only the relevant markets directly affected by the decisions, but also the whole subsector to which the market belongs. This implies that, for example, the deterrent effects of an important airline merger decision with competition concerns limited to specific routes will be felt across the whole air passenger transport sector, meaning that other airlines will be induced to abandon likely anti-competitive mergers. This assumption has some empirical support – a survey by Deloitte (2007) suggests that mergers in a given sector in the UK are more likely to be abandoned or modified if there has been a recent inquiry by the UK competition authority in the sector (see also Gordon and Squires 2008). Moreover, there is some evidence that cartel detection in a market decreases the rate of cartel formation in related markets (Harrington 2008).

Distinguishing Between the Impact on Poorer and Richer Households

The QUEST III model was extended to allow investigating the effects of the European Commission’s competition policy interventions on distributional outcomes. For that purpose, a distinction is made between poorer and richer households. Poorer households have incomes only from wages, transfers and benefits, and consume their incomes every period, while richer households have additional sources of income as they own capital and are active in the financial market.

Competition policy has a significant and positive impact on growth and jobs

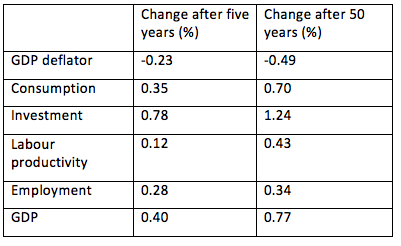

The mark-up shocks resulting from the direct and deterrent effects of merger and cartel decisions taken by the European Commission is a 0.85% decline, which corresponds to a 6.7% reduction in the mark-up. The model simulations show that, as a result of this reduction in mark-up, EU GDP increases by 0.4% after five years and by 0.8% in the long run, while employment goes up by 0.3% – equivalent to around 650,000 additional jobs. These effects are of the same order of magnitude as the effects of the implementation of the Service Directive across EU Member States (Monteagudo et al. 2012).

The economic logic of these simulations can be explained as follows (Table 2). Competition authorities’ interventions increase competition in the market, which reduces profit margins (or mark-ups) and price levels, contributing to lower inflation (or a reduction in GDP deflator). Lower price levels stimulate consumer demand. In order to satisfy this greater demand, firms invest in production capacity and better technology (leading to an increase in labour productivity) and hire more workers (leading to an increase in employment). Investment and employment increase because the negative direct effect of reduced profitability is more than offset by the positive effect of the increased demand. All these changes are then reflected in a GDP increase.

Table 2 Macroeconomic impact of mark-up shocks

Important Redistributive Effects

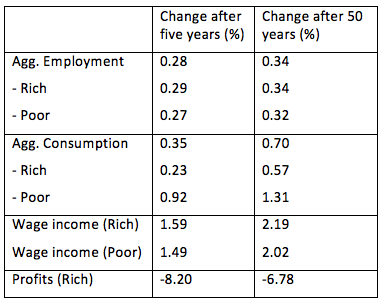

The model simulations also assess the distributional effects of the European Commission’s merger and cartel decisions (Table 3). The simulations show that competition policy has important redistributive effects.

Table 3 Distributional effects of the mark-up shock

Poorer households (low skilled and consuming all their resources in each period) increase consumption proportionally more than richer households (high skilled and savers) – four times as much after five years. While there is a similar increase in demand for both skilled and unskilled labour and consequently similar wage increases for both types of households, the substantial deterioration in profits and decrease in income from financial assets are only borne by richer households. This supports the view that competition policy interventions benefit the poorest in society.

A Robustness Test

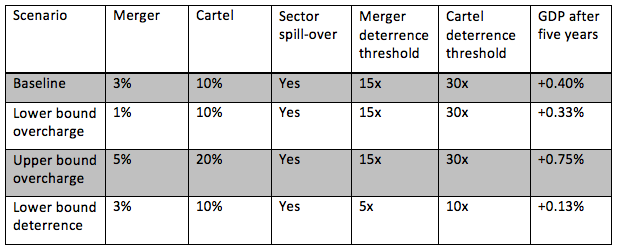

This work is a first contribution to a more comprehensive analysis of the impact of competition policy, going beyond direct price effects and integrating deterrent and macroeconomic effects. Such an analysis is challenging and the policy simulations presented here necessarily rely on a number of assumptions, in particular concerning price overcharges3 and the size of deterrent effects. A robustness test has therefore been carried out to assess the sensitivity of the results presented above to key assumptions made (Table 4).

Table 4 GDP effect after five years under different scenarios

A comparison of the results in the lower bound and the upper bound overcharge scenarios shows that competition authorities can double the impact of their decisions if they intervene in markets with more significant anticompetitive effects, such as highly concentrated markets. This table also illustrates the importance of assumptions on deterrence. More accurate estimates of deterrent effects, in particular of the size of the spill-over effects across sectors, could narrow the range of estimated GDP effects. This also means that it is worthwhile for a competition authority to pursue cases with limited anticompetitive effects but with significant deterrent effects.

More Work Remains to be Done

This column, while more comprehensive than other works based on customer savings approaches, gives only a partial view of the overall impact of competition policy, as it does not include an assessment of the macroeconomic effects of competition policy interventions in other areas of antitrust or in state aid control. Moreover, it does not cover alternative transmission channels through which the impact of competition policy may be felt, such as increased business dynamism. Finally, available information on the sector distribution of Commission cartel and merger decisions could be further exploited to analyse the differential effects of competition decisions affecting different sectors of the economy. All these issues could be areas for further research.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are purely those of the writers and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the European Commission.

See original post for references

Of course, the dangers of monopolies was central to the analyses of most of the early ‘greats’ of Economics, from Adam Smith onward. More recent economists have tended to talk about the horrors of monopolies, without actually understanding the dynamics of monopoly and anti-competitive behaviour. As an obvious example, if they understood it they would note the very high wages in certain sectors as proof of a lack of real competitive markets (most obviously in finance).

I’m always a little suspicious of some anti-monopoly regulators as I think its been increasingly obvious that some use that rhetoric to further the aims of corporations and public services – in other words, they’ve been captured by the companies they are supposed to regulate. The biggest problem is the promotion of ‘competition’ as a solution to lower the cost of public services, from medical care to waste collection. At the moment, I’ve a pile of garbage on my local street thanks to ‘competition’ policy from the EU, which resulted in the destruction of a perfectly functional public collection service in favour of multiple companies who only have an interest in collecting from ‘easy’ clients, not multiple occupancy houses. It didn’t seem to occur to those advocating these policies that waste collection was mostly a public service for a very good reason – the private sector could not do it competently.

Another example is in retailing – there has been a constant battle between those advocating ‘competition’, and strict planning policies on the location of supermarkets and big box retailers. Shockingly, in some cases it is public competition bodies that actually advocate on behalf of the big retail companies on the basis that local planning laws ‘prevent competition’. In reality, strict planning laws are necessary to prevent retailers hanging on the coat tails of public investments in roads to create localised monopolies around giant stores. It is only by forcing a mix of small to medium stores within urban areas that you can have strong local choice and competition.

PK’s comment is profoundly important, as public services and local zoning control seem to be under threat everywhere. I really hope the authors read it and will consider the ramifications in any future research.

. . . in favour of multiple companies who only have an interest in collecting from ‘easy’ clients, not multiple occupancy houses

“Easy clients” is a phrase that goes under cherry-picking, the business model of the insurance industry (to a first approximation). . . Not to mention the charter school movement and so forth.

If I may be forgiven for turning exclusively to American cases, under Bush-Cheney there was de facto canning of anti-trust. Take one. The Clinton administration’s suit against Microsoft petered out by the time U S courts and Bush-Cheney finished it off. It was left to the (relative) political independence of the EU to sue with success for unbundling of browser from Microsoft’s operating system. As comic relief for the ages we have this (wiki):

There are two other interesting cases. Continuing with “high tech”, from Fortune SEPTEMBER 3, 2015:

So much for Silicon Valley’s meritocracy. Of course, nothing will stop (even a day’s bad publicity) plutocrats arraying themselves as philosopher-kings while guiding us to a charter school future.

Now from the Wall Street Journal Aug. 7, 2014

Your day is complete with another Goldman “attribution”.

While a carburetor only works when the flows of air and gas are regulated by port size openings, the economy needs regulators with similarly rigid specifications in order to get/keep things running smoothly. The prevalence these days of disruption philosophy leaves flows to chance, or to the benefit of those with asymmetrical information or capacity, such as amazon not charging sales tax, that they should not be allowed to exploit

Working my way through Capital (which is monotonous and frankly essentially unreadable and a crime against the very idea of using words to convey meaning, but I digress) and I see why Michael Hudson calls Marx the last of the Classical Economists. He references and quotes Smith, Ricardo, and many others extensively. Though to be fair much of the time it’s so he can smugly diss them and claim they were wrong about something, usually while himself also being wrong.

You’ll learn far more about Classical Economics just through Marx’s references than you will through entire volumes of modern economic textbooks.

Thing about “wrong” is that it is relative, not binary.

Here’s a relevant link:

http://khn.org/news/as-hospital-chains-grow-so-do-their-prices-for-care/

This is why using the word capitalism to describe our current system makes no sense. Of course monopoly is bad. That’s one of the foundational observations of market-based economics.

Which is why our system does so much to protect monopoly power (especially back here in the New World): we aren’t capitalists in any meaningful sense of the word.

Tim Wu’s book “The Master Switch” is excellent on the topic.

One problem with the term “monopoly” is that it is most often understood to be 100% market share.

Sorry bub, but a company can be below the 50% mark in market share and still be market distorting, if its share is the biggest of the pack.

Also, often their size in the primary market is not the issue. But how that size can be leveraged to affect other markets.

Monopoly is the bane of capitalism.

Left to itself capitalism tends toward monopoly.

https://therulingclassobserver.wordpress.com/2016/05/24/religious-capitalists-vs-common-sense-capitalists/