By Peter H. Lindert, Distinguished Professor of Economics, University of California – Davis and Jeffrey G. Williamson, Laird Bell Professor of Economics, Harvard University. Originally published at VoxEU

Americans have long debated when the country became the world’s economic leader, when it became so unequal, and how inequality and growth might be linked. Yet those debates have lacked the quantitative evidence needed to choose between competing views. This column introduces evidence on American incomes per capita and inequality for two centuries before World War I. American history suggests that inequality is not driven by some fundamental law of capitalist development, but rather by episodic shifts in five basic forces: demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labour-saving technological change.

When did America become the world leader in average living standards? There is little disagreement about how American incomes have grown since 1870, thanks to the pioneering work of Simon Kuznets and many others. Yet income estimates are weak and sparse for the years before 1870. In spite of that, our history textbooks imply that the road to world income leadership was paved by the institutional wisdom of the Founding Fathers and those who refined it over the two centuries that followed. While those institutions were well chosen, in a new book we show that British America had attained world leadership in living standards long before the Founding Fathers built their New Republic (Lindert and Williamson 2016). Furthermore, the road to prosperity was far bumpier than the benign textbook tales of American economic progress imply.

Was income ever distributed as unequally between the rich, middle, and poor as it is today? As we are constantly reminded, the rise in US inequality over the half century since the 1970s has been very steep. The international research team led by Atkinson et al. (2011) has charted the dramatic 20th century fall and rise of top incomes in countries around the world, including the US. However, until now evidence was not available for before WWI. Thus, there is still no history of American income inequality for the two centuries before WWI, aside from a few informed guesses. We now supply that distributional evidence back to 1774.

A new approach with new data

Armed with new evidence, we apply a different approach to the historical estimation of what Americans have produced, earned, and consumed. National income and product accounting reminds us that we should end up with the same number for GDP by assembling its value from any of three sides – the production side, the expenditure side, or the income side. All previous American estimates for the years before 1929 have proceeded on either the production or the expenditure side.

We work instead on the income side, constructing nominal (current-price) GDP from free labour earnings, property incomes, and (up to 1860) slaves’ retained earnings (that is, slave maintenance or actual consumption). Our social tables build national income aggregates from details on labour and property incomes by occupation and location for the benchmark years 1774, 1800, 1850, 1860 and 1870. No such income estimates were available for any year before 1929 until now.

Our unique approach leads to big rewards. One reward is the chance to challenge the production-side estimates using very different data and methods. As we see below, our estimates are often dramatically different. An even bigger reward is that the income approach exposes the distribution of income by socio-economic class, race, and gender, as well as by region and urban-rural location.

New Findings About American Income Per Capita Leadership

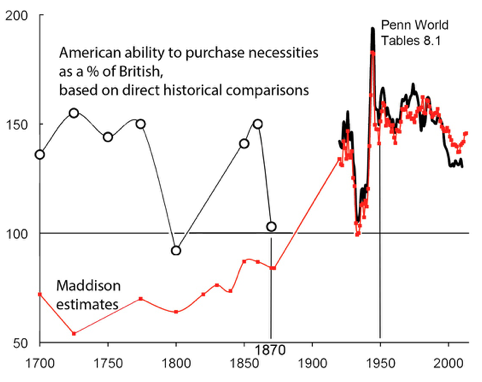

America actually led Britain and all of Western Europe in purchasing power per capita during colonial times. Britain’s American colonies were already ahead by 38% in 1700 and by 52% in 1774, just before the Revolution (Figure 1). Angus Maddison’s (2001) claim that American income per capita did not catch up to that of Britain until the start of the twentieth century is off by at least two centuries.

Figure 1 Real purchasing power per capita: America versus Britain, 1700-2011

Since the 1770s, America’s big income per capita advantage over Britain has not increased. The only historical moment in which the US soared well above its colonial lead over Britain and the rest of the world came at the end of WWII. Since then, the American per capita income lead over Britain has fallen back to colonial levels.

But note the vulnerability of America’s relative income per capita to costly wars. Fighting for independence may have cut American income per capita by as much as 30% between 1774 and 1790. The causes seem clear – war damage, mortality and morbidity among young adult males, the destruction of loyalist social networks, a collapse of foreign markets for American exports, hyper-inflation, a dysfunctional financial system, and much more. Then, by 1860, the young republic had regained its big income lead, this time by as much as 46%. This was a period of rapid catching up with and overtaking of Western European per capita incomes, including that of Britain. Fast per capita income growth and even faster population growth made the America the second biggest economy in the world by 1860. However, the US lost most of that big lead (again) during the destructive Civil War decade. It gained the lead back once more by 1900, and briefly lost it (again) in the Great Depression of the 1930s.

American colonists probably had the highest fertility rates in the world, and their children probably had the highest survival rates in the world. Thus, the colonies had much higher child dependency rates, and family sizes, than did Europe – and even higher than the Third World does today. What was true of the colonies was also true of the young Republic. It follows that America’s early and big lead in income per capita was exceeded by its early lead in income per worker.

New Findings About American Inequality

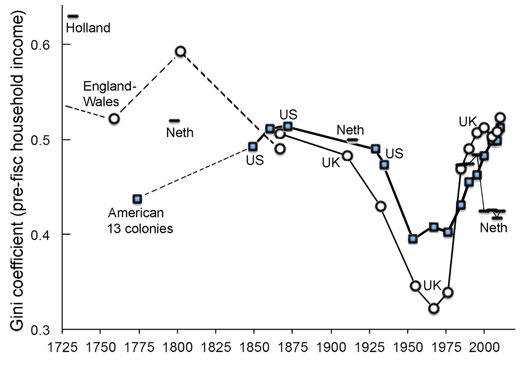

Colonial America was the most income-egalitarian rich place on the planet. Among all Americans – slaves included – the richest 1% got only 8.5% of total income in 1774. Among free Americans, the top 1% got only 7.6%. Today, the top 1% in the US gets more than 20% of total income. Colonial America looks even more egalitarian when the comparison is by region – in New England the income Gini co-efficient was 0.37, the Middle Atlantic was 0.38, and the free South 0.34. Today the US income Gini is more than 0.5, before taxes and transfers. Colonial America was also far less unequal than Western Europe. England and Wales in 1759 had an income Gini of 0.52,and in 1802 it was 0.59. Holland in 1732 had an income Gini of 0.61, and the Netherlands in 1909 had 0.56. Also, if you agree with neo-institutionalists that economic equality fosters political equality, which fosters pro-growth policies and institutions, then America’s huge middle class is certainly consistent with the young republic’s pro-growth Hamiltonian stance from 1790 onwards. That is, the middle 40% of the distribution got fully 52.5% of total income in New England, the cradle of the revolution!

As Figure 2 shows, it did not stay that way. A long steep rise in US inequality took place between 1800 and 1860, matching the widening income gaps we have witnessed since the 1970s. The earlier rise was not dominated by a surge in the property income share, as argued by Piketty (2014). Rather, this first great rise in inequality was broadly based, with widening income gaps throughout the whole income spectrum – rising urban-rural income gaps, skill premiums, gaps between slaves and the free, North-South income gaps, earnings inequality, and even property income inequality.

Figure 2 Income inequality in America, Britain, and the Netherlands, 1732-2010

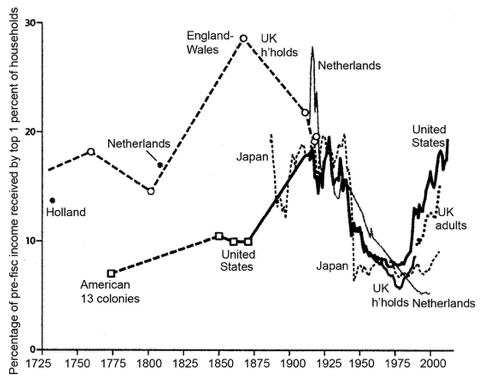

From 1870 to WWI, American inequality moved along a high plateau with no big secular changes. Rather, the big drama followed afterwards. Figure 3 documents that the income share captured by the richest 1% fell dramatically between the 1910s and the 1970s, and the share of the bottom half rose, for almost all countries supplying the necessary data. This ‘Great Levelling’ took place for several reasons. Wars and other macro-shocks destroyed private wealth (especially financial wealth) and shifted the political balance toward the left. The labour force grew more slowly and automation was less rapid, improving the incomes of the less skilled. Rising trade barriers lowered the import of labour-intensive products and the export of skill-intensive products, favouring the less skilled in the lower and middle ranks. And in the US, the financial crash of 1929-1933 was followed by a half century of tight financial regulation, which held down the incomes of those employed in the financial sector and the net returns reaped by rich investors. We stress that this correlation between high finance and inequality is not spurious. Individuals with skilled financial knowledge have been well rewarded during the two inequality booms, and heavily penalised during the one big levelling (or two, if the 1776-1789 years are included).

Figure 3 Income share received by the top 1%, four countries over two centuries

The equality gained in the US during the Great Levelling slipped away after the 1970s. The rising income gaps were partly due to policy shifts. The US lost its lead in the quantity of mass education, and its gaps in educational achievement have widened relative to other leading countries. Financial deregulation in the 1980s also contributed powerfully to the rise in the top income shares and also to crises and recessions. A regressive pattern of tax cuts allowed more wealth to be inherited rather than earned. These policy shortfalls are, of course, reversible and without any obvious loss in GDP.

History Lessons

American history suggests that inequality is not driven by some fundamental law of capitalist development, but rather by episodic shifts in five basic forces – demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labour-saving technological change. While some of these forces are clearly exogenous, others – particularly policies regarding education, financial regulation, and inheritance taxation – offer ways to check the rise of inequality while also promoting growth.

See original post for references

Income data is valuable but wealth is power.

If I am a skilled laborer in 1840 Massachusetts I probably command a high wage and live a nice life. But I can lose that job and be destitute in no time flat. If I own a plantation in South Carolina and don’t screw up by borrowing and investing stupidly, I have a guaranteed high income for life, and can pass that on to my children in a way the skilled worker cannot. My position as a property holder also gives me leisure time to engage in politics and social standing that the skilled worker does not have. It’s all well and good to talk about how Americans enjoyed very high relative wages, but wealth was where it’s at.

Oh, and no mention of Primitive Accumulation. Where, per chance, did all the wealth those colonists enjoyed come from? I wonder if they talk about it in any detail in the book.

This is a nice complement to Securing the Fruits of Labor: The American Concept of Wealth Distribution, 1765–1900, by

James L. Huston, recently republished by Louisiana State University Press. This new data confirms the importance of economic equality in the founding of the republic. But as Huston details, the founders unfortunately failed to institutionalize government policies that would ensure economic equality other than discarding British common law on entails and primogeniture.

In a similar vein….

What this report finds: Income inequality has risen in every state since the 1970s and in many states is up in the post–Great Recession era. In 24 states, the top 1 percent captured at least half of all income growth between 2009 and 2013, and in 15 of those states, the top 1 percent captured all income growth. In another 10 states, top 1 percent incomes grew in the double digits, while bottom 99 percent incomes fell. For the United States overall, the top 1 percent captured 85.1 percent of total income growth between 2009 and 2013. In 2013 the top 1 percent of families nationally made 25.3 times as much as the bottom 99 percent.

Why it matters: Rising inequality is not just a story of those in the financial sector in the greater New York City metropolitan area reaping outsized rewards from speculation in financial markets. While New York and Connecticut are the most unequal states (as measured by the ratio of top 1 percent to bottom 99 percent income in 2013), nine states, 54 metropolitan areas, and 165 counties have gaps wider than the national gap. In fact, the unequal income growth since the late 1970s has pushed the top 1 percent’s share of all income above 24 percent (the 1928 national peak share) in five states, 22 metro areas, and 75 counties.

http://www.epi.org/publication/income-inequality-in-the-us/?utm_source=Economic+Policy+Institute&utm_campaign=9c279245cd-Unequal_States_06_16_20166_16_2016&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_e7c5826c50-9c279245cd-58538293

Disheveled Marsupial…. seems every time some confuse scripture with data driven conclusions…. everything goes to shite…

An interesting discussion. I note the mention of the high fertility rate and the high infant survival rate. The early Republic was shored up by ideas of Republican Motherhood, which may have unintentionally set the stage for the rigidity of U.S. gender roles. Yet the cult of Republican Motherhood also produced huge growths in population.

And yet: I recall a study a few years back that a large proportion of soldiers called up or volunteering for the Civil War were rejected on the grounds of health. Parts of the country by the 1860s were swaths of malnutrition. So something was going wrong: U.S. agricultural practices have always been advanced, too. So there is a defect here somewhere: Causes of malnutrition? Limited diet? Lack of income in the countryside?

I just finished The Masters of Empire, an interesting read about the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatami. The Odawa, especially, were involved for years in an enormous cross-country trade. So the prosperity extended to the Native Americans of the Great Lakes, which make explain why the Ojibwe peoples were able to prevent themselves from being “removed.” (But others may have comments on this hypothesis.)

Thanks, DJG, for the mention of The Masters of Empire! I just ordered a copy from Powells.

I think the issue of malnutrition was associated with urban life. In the Napoleonic Wars the French recruiters focused on strapping, strong rural recruits until they realised that the dropped like flies from disease – unlike the pale weedy urban recruits who were more or less immune to diseases of crowding in army camps. In WWI the British were appalled at how weak so many of their urban conscripts were – many could hardly do basic things like lift their Lee Enfields (previous to this, most soldiers were recruited from rural areas). It led to an increased focus on urban public health in early 20th century UK, in particular making sure children got milk and eggs. I would guess that the same applied in Civil War era US. I’d also note that a lot of immigrants were recruited, many were coming from famine in Ireland and other parts of Europe.

A major driver of inequality in the US since the mid seventies has been the massive change in our tax code. Not only has the nominal rate for top earners been sharply reduced, loopholes benefiting the wealthy have proliferated. Corporate effective tax rates have also declined by more than half, even more so for the largest enterprises. Even the definition of report-able income has changed.

The trillions of hidden offshore monies originate from the US as well as corrupt countries such as Russia and Nigeria. I would love to see NSA focusing it’s resources on these felons. Either we would balance the budget or the blowback would restore our constitutional privacy rights.

. . . to see NSA focusing it’s resources on these felons

A very interesting question for some time: what are the laws/forces authorized in practice pressing against money laundering, finance of terrorism, tax evasion?

That political bargaining behind the scenes broker protection of certain parties seems unavoidable. The technical means and the laws have been there at least since Bush-Cheney.

In short is there a protection racket?

“Among free Americans, the top 1% got only 7.6%.”

Am I reading this wrong, or are the authors calculating their Gini coefficient excluding non-free Americans? So colonial American was the most egalitarian place on earth, ignoring the slaves, because who cares about them, right?

I, too, was unclear about how the slaves fit in. And slaves made up a significant percentage of the population even in the 1770s.

At the beginning of the piece they calculate the retained earnings (maintenance an/or consumption costs) of slaves. Those “earnings”, appear, to be slave income.

The sentence right before that one gives the figure if they included slaves:

“Colonial America was the most income-egalitarian rich place on the planet. Among all Americans – slaves included – the richest 1% got only 8.5% of total income in 1774.”

K,so…”episodic shifts in five basic forces – demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labour-saving technological change.” demography (wasp),education policy (student loans),trade competition (TPP, competition ruins the free market, you know), financial regulation (dismantling glass steagall), and labour-saving technological change (robots)….a regular dystopians utopia.What’s that? Afraid for your future? Get used to it, if you’re haven’t already. That or be rich.

Reading now. Keep in mind this is a mainstream economics exercise in “cliometrics”, the retroactive imposition of assumed categories of neoclassical economics upon a past that may not conform to its framework of “factors of production” – labor, land and capital – clearly intended for the analysis only of the capitalist form of production.

Hence the angst to “suggest” that ” that inequality is not driven by some fundamental law of capitalist development”. I have no doubt that this was a presupposition, and not a “conclusion”, for the book.

Brad you raise a fascinating historical and methodological point when your argue that the analysis in this article may have lots to do with a “retroactive imposition of assumed categories.”

You add to this critique with your insightful comment that the authors belief that inequality is not driven by some fundamental law of capitalist development– is probably a presupposition rather than a “conclusion,”

It would be great if you could expand on these thoughts a bit more.

I think you are misreading the implication. This is an argument against Piketty, which I’ve seen as saying capitalism inevitably produces high and rising levels of inequality. This piece is saying it is the result of specific factors, many of which are the result of political decisions. Societies can decide to have inequality or not.

However, a big shortcoming of this piece is that it fails to consider taxes, and that’s the defect of such a long time frame. Using taxes to redistribute income is a 20th century idea.

It also fails to consider the pistol and the bullwhip.

“American history suggests that inequality is not driven by some fundamental law of capitalist development, but rather by episodic shifts in five basic forces: demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labour-saving technological change.”

Sorry, you are jumping in at an arbitrary point here. “demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labour-saving technological change” were developed within the capitalist context, ie, the few controlling profit and keeping capital out of the hands of less privileged people. If you cite the above, it is within the capitalist context. It wasn’t socialism that brought us to this point.

You can’t claim we live in a capitalist society, that capitalism has done great things in America, and then claim capitalism has nothing to do with the situation we find ourselves in.

This history of capitalism is that capitalists don’t like sharing the fruits of the workers’ labor with them.

This doesn’t mean hate capitalism, just take it for what it is.

https://therulingclassobserver.wordpress.com/2016/06/15/ruling-class-axioms/

“American history suggests that inequality is not driven by some fundamental law of capitalist development, but rather by episodic shifts in five basic forces – demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labour-saving technological change. While some of these forces are clearly exogenous, others – particularly policies regarding education, financial regulation, and inheritance taxation – offer ways to check the rise of inequality while also promoting growth.”

Are economists just bad historians in addition to being pseudo-social scientists, or are the authors just too stupid for words because I happen to disagree with their conclusions? This seems to be an attack on Piketty’s conclusion: r > g. The rate of return on capital is greater than the growth of the economy in which the capital is invested. Piketty has been roundly attacked, left, right, bourgeoisie and Marxist alike agree to disagree with Piketty’s little formulaic conclusion. If you tear the profit out of the economic mode of production and replace it with “at cost” delivery, you provide the same material gross domestic output without the fictitious capital, which produces a surplus of financial wealth. That is, when GM makes and sells a full size pick up truck, it sells it for more than it costs to produce it. Capitalism takes profits in the form of money in excess of the money it costs to pay for all of the inputs of production, including marketing and out sized C-Level executive salaries.

If GM provided the same truck at cost, the sales price would be less than under the capitalist mode of production, but there would still be a whole truck to safely drive around in for some years to come. GM does not take profits in the form of tires and windshields or even 1/ 2 of truck, it takes it profits in money. The economy can still grow at the same rate, that is still have the material production and services rendered without profits as with, but without the rate of financial return being greater than the growth of the economy as a whole. A cooperative mode of production, with “at cost” provisioning of goods and services would have r = g. The capitalist mode has r > g.

Now that the mystery of what this article is really about is made plain, and it is not about good policy formulation to uncover the causes of inequality, political, economic and otherwise, let’s look at the substance of the “forces” at work to produce inequality according to the authors.

“five basic forces – demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labour-saving technological change” are said to be the culprits and not some law of capitalist development!

To begin with, it is the combination of the nation-state and the private market that together provide the rule of capitalism. The power of the private market to capture the authority of the state, by force, bribery or overwhelming wealth to bend the democratic process to place business friendly politicians in the offices of power results in variables the authors seems to value so highly. The state and the market working in concert is government by capital or capitalism. The capture of this system by power elites to acquire and retain power for their small demographic, the 1%, has been renewed with a vengeance under the name of Neo-Liberalism.

“The equality gained in the US during the Great Levelling slipped away after the 1970s. The rising income gaps were partly due to policy shifts. The US lost its lead in the quantity of mass education, and its gaps in educational achievement have widened relative to other leading countries. Financial deregulation in the 1980s also contributed powerfully to the rise in the top income shares and also to crises and recessions. A regressive pattern of tax cuts allowed more wealth to be inherited rather than earned.”

The policy shifts just happen to benefit the 1% and harm just about everyone else. Of course, the renewed emphasis on profiteering from anything not already nailed down by the public resulted in the privatization of public education, creating new profit opportunities and diminishing the empowerment of the citizenry. Instead of renovating schools and making them as air conditioned comfortable as an enclosed shopping mall, the government began a criminalization rampage against the citizenry and built jails instead. This was lead by corporate jails for profits and the continuation of the criminalization of drug usage is being lobbied for by Police unions to maintain their status and power in civil society.

The financial deregulation and tax cuts to the wealthy along with inheritance tax being destroyed as a political check on dynastic wealth accumulating overwhelming political dominance is well known to NC readers, and would certainly be considered a primary law of capitalist development, the capital formation necessary to fund the capitalist enterprises, whether farms, plantations or factories. The authors would obliquely denigrate iron laws of capitalism rising from Piketty rather than the hiding in plain sight capture of the law making capacity of the state to enshrine profit making wherever and whenever requested. Their statement that these polices are reversible further emphasizes the 5 policies to blame and not some structural feature of the beneficent capitalist order, which of course, has not development characteristics worth mentioning. An odd thing for economists to delve into poly-sci and distract attention from economics. But then, that is their function in these Neo-Liberal times of uncertainty and discontinuity.

The financial deregulation and tax cuts to the wealthy along with inheritance tax

Core ideology of Paul Ryan, party ideologist. And to the extent the U S is a one-party state, that party’s core. The program for some years, perfectly open to viewing, is zero taxation of income from wealth and zero inheritance taxation.

The failure of the market in the editing of journalism: it can’t say this is the Free Lunch Movement.

I wonder how susceptible the GINI data is to change if you remove “retained earnings” from slaves.

Maybe I am wrong, but I was always under the impression that the economics of slave ownership was related to the economics of horses/ mushing dogs.

Seems a bit strange (conceptually) to include the maintenance of capital in GINI, but maybe it doesn’t change the numbers much (so irrelevant to the overall argument).

It seems to me that all this occurred within the capitalist system, ie, capitalist collecting profit and keeping it out of the hands of ordinary people as much as possible.

History has shown capitalist fighting the “people” to preserve this status quo as much as possible.

https://therulingclassobserver.wordpress.com/2016/06/15/ruling-class-axioms/

Piketty is wrong about capital because he treats wealth as accretions of previous income flows, rather than as the result of human mentation creating new science and technology. Only if you read Alexander Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures will you find that the political economy of the republic is supposed to based on that conception of wealth creation, in direct opposition to the political economy of Smith, Ricardo, Malthus, ie, British East India Co. Huston writes about this explicitly. So does Michael Hudson in his book on the American System.

The other key conceptionof the American republic is that all economic activity must promote the General Welfare – see my Introduction to the Kindle edition of Adair & Hamilton’s 1937 The Power to Govern. Almost all flavors of economic thougt entirely ignore this crucial desideratum even though it is what distinguishes the creation of the American republic as a sharp break from the mercantilism of feudalistic and monarchic states. Huston and Hudson touch on this area in their discussion of Hamiltonian industrialization versus the peculiar institution of slavery, but they are not thorough enough to fully draw out the implications.

To fully understand current events in their true historical context, it helps to understand that consetvatism is an unrelenting assault on the idea of the state forcing economic activity to promote the General Welfare. In other words, a return to aristocracy, just like Agee argues in his famous internet post of over a decade ago “What is consetvatism?”.

Piketty is wrong about capital because he treats wealth as accretions of previous income flows, rather than as the result of human mentation creating new science and technology.

Um, I don’t think that’s generalizable. The wealth of America was in arable land, water, wood, and minerals taken from the indigenous people. Mentation didn’t get that job done–brute force and human muscle did. I would also suggest a gander at Marx’s work on Primitive Accumulation (enclosure, displacing tenants for sheep, robbing foreigners like Indian Maharajas, brokering the slave trade).

Capitalists will always tell you they have everything because of their “genius” and hard work. I submit that that is a gross oversimplification at best.

This is in reply to Tony Wikrent above.

Certainly is. Genius with what skills precisely? Choosing their Parents?

If you 100 acres of land that contains the world’s largest concentration of gold, or copper, or zinc, or whatever, and you do not posess the knowledge of mining, building mining equipment, assaying and refining ores, how to create and control fires hot enough to refine ores, etc., etc., pray tell me, how much wealth do you actually have?

The man who owns those 100 acres could easily know none of those things yet the vast bulk of the profits on those processes goes to him via ownership, not knowledge. And in North America or Australia, how did he get those 100 acres in the first place?

Actually this depends on when the land was acquired, pre independence if you knew the right people you got the land in a grant from the crown. When the US got going with major mining ventures, it was first come first gets, with local rules on how much one could hold (typically the first discover got a double share, see history of Virginia City NV) But typically the first finder sold out for far to little (as again at Virginia City,) and drank himself to death. Later Virginia city buyouts occurred on the San Francisco stock exchange,or because of bankers and speculators.

Thank you for highlighting one reason why Marx has proven to be as disastrous in application as Adam Smith and Milton Friedman: none understands that wealth is created only by the application of technology which in turn arises from scientific progress. If technology is never applied to the hypothetical 100 acres there will never be any wealth to extract, loot, monetize, profit from, or whatever term you wish to use.

“American history suggests that inequality is not driven by some fundamental law of capitalist development, but rather by episodic shifts in five basic forces – demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labour-saving technological change.”

What about tax policy? Why isn’t it included?

Oh wow! thanx

I knew all those categories of credit derivatives, junk CDO concoctions, and Ponzi schemes were simply to fool us!

Some good data here, but there are some very loud “buts”, IMO, for example:

“…in a new book we show that British America had attained world leadership in living standards long before the Founding Fathers built their New Republic.” — Living standards for whom, exactly? Surely not the many millions of people living out their doomed-to-be-wretched lives under the thumb of empire, whose blood, sweat, toil and natural inheritance were being plundered in order to enrich their colonialist masters. And even at home in Merry Olde England, the hordes of industrial-revolution laboring classes – conveniently forced into wage slavery via the elites-driven enclosure movement, right down to all but their youngest children – were they around to be asked, might well dispute the “world leadership in living standards” braggadocio. What a load of elitist piffle by the authors of this piece.

And of course those in Britain’s American colonies learned from their former masters all too well, in similarly building their future imperium via the tried and true methods of ethnocide, slavery and mass-scale looting. Don’t get me wrong, “Yankee ingenuity” also played a significant role, but no original-sin land grabbing and native genocide, no colonies and no room for the westward expansion necessitated by ongoing immigration and by having all those kids, much less to grow strong enough to start stealing “business” from their former cartel bosses.

Also, I am highly skeptical of the “income disparity … including slaves” assertion. How does one reliably compute income for someone with no rights, whose property, loved ones and life can be taken at any time, for any reason deemed “reasonable” by their owner? And how much of said income was stolen by offering said slaves the “right to buy their freedom”, which was surely exposed as eminently revokable on many occasions, after the extortion money was handed over?

Looking at the data.

1750

The US was a new country with most of the land unclaimed.

People could claim land and build on it leaving them mortgage free.

No one was taking profit from their labour and all the income they earned was pretty much their own.

1750 – 1875

Less free land is available and rent and mortgage payments rise.

Capitalism takes hold with someone else looking to profit from your labour.

1875 – 1935

Unions and organised labour get stronger giving them more of the rewards from their labour.

1935 – 1975

Keynesian redistributive capitalism with strong progressive taxation.

1975 – now

Union and organised labour power smashed.

Low tax rates on high earners.

Return to primitive, 19th Century Capitalism.

The Gini coefficient is the best guide to the distribution of wealth between rich and poor.

The UK starts the industrial revolution earlier and its labour force start forming unions earlier.

Once the US is carved up it becomes pretty much the same as everywhere else, it is no longer a new land with lots of free stuff.

The US has a meaner approach to Keynesian redistributive Capitalism.

The object of the exercise is to leave those at the bottom with just enough to survive and breed.

When they couldn’t take the labour of the masses for profit, they took their money in rent and interest payments.

No classical economists ever saw the poor rising out of a basic subsistence living.

Adam Smith:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

With slavery you own your workers without slavery you rent them.

US slave owners argued they treated their workers better because they owned them rather than renting them, a valid point at the time.

“Money is a new form of slavery, and distinguishable from the old simply by the fact that it is impersonal – that there is no human relation between master and slave.” Leo Tolstoy

After a one hundred year deviation we are heading back to the norm.