Yves here. We’re featuring this post more as a critical thinking exercise rather than for the findings of the study posted below, although they are also of interest. As you’ll see, a study performed using 2000 to 2005 data in Germany found that workers who’d lost their jobs didn’t fare as bad as average outcomes suggested, since some were hit hard, while 25% had reached higher of pay in five years.

To which I say “Huh?”

First, even the relatively advantaged 25% would often suffered loss of income and presumably relative savings over the part if not all of the five year period. To reach better conclusions, you’d need to estimate lifetime earnings and see if they had prospects of coming out net ahead, based on the period of no/lower income and to what degree the later, higher earnings more than compensated for that.

Second, 25% better off still confirms a grim picture, that 75% were worse off on a long-term basis.

Third, the study time frame happened to occur during a period of strong growth in Germany. From the World Bank:

Fourth, German collective bargaining representation has fallen since 2000, which generally suggests a weakening of labor rights (readers who have more knowledge of the situation in Germany are encouraged to speak up; a quick search was not terribly informative). A European Union Trade Council report in 2020 found that the percentage of German workers covered by collective bargaining agreements had fallen by 14% to 54%, below the EU average of 61%. So Germany is far from the worker paradise that some assume it to be. The EU states with much higher collective bargaining levels: Denmark, Finland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Italy, Austria, Netherlands, Finland, Belgium, France, Luxembourg, Sweden. Austria leads the pack at 98%.

Mind you, what bothers me is not the findings (the findings are the findings, after all) but the spin, staring with the dishonest labeling of job loss as “job displacement”. “Job displacement” connotes that all of those fired eventually find new employment, when some never do, or at least not at any kind of reliable work.

In addition, it’s one thing to say, “Earlier information on this topic might not be as terrible as it appeared” as opposed to the shading taken here, that unevenly distributed long-term results from job loss means they are not a biggie. Arguably less bad is still bad.

An example of what I mean:

Interestingly, both groups exhibit similar overall mobility – changing industries, occupations, and regions multiple times – but adjusters make decisive moves immediately after displacement, while casualties experience delayed and unstable transitions.

So it is entirely the worker’s fault if they do not land well. The authors’ posture is that the laggards had not acted “decisively” enough.

Now admittedly, there likely were some job losers who were shocked and arguably took more time than was optimal before getting serious about securing new employment. But from observing some unceremonious exits, how fast one lands is to a significant degree a function of luck and the utility of one’s personal networks.

By Eric Hanushek, Paul and Jean Hanna Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution Stanford University; Simon Janssen, Senior Researcher German Institute for Employment Research (IAB), and Jacob D Light. Originally published at VoxEU

Decades of research have confirmed that job displacement causes significant and persistent earnings losses. This column presents new evidence from workers displaced during firm closures in West Germany between 2000 and 2005 which suggests that these losses are in fact much more heterogeneous than previously documented, and that the large average losses documented in previous work are heavily influenced by a minority of workers who experience catastrophic earnings declines.

A recurrent and urgent policy debate revolves around the long-term consequences workers face after job displacement events like firm closures or mass layoffs. Historically, studies have shown that such displacements trigger substantial and persistent earnings losses for affected workers. An extensive literature – dating back to Jacobson et al. (1993) and including influential recent studies by Davis and von Wachter (2011) for the U.S. and Schmieder et al. (2023) for Germany – documents persistent earnings losses of 15-25% following displacement, with older and less-educated workers disproportionately affected.

Much of this literature, however, has concentrated on average effects within and across groups of different workers, leaving a significant gap in our understanding of the distribution and heterogeneity of these losses among workers. In a recent paper (Hanushek et al. 2025), we use new empirical methods and comprehensive administrative data from Germany to characterise the full distribution of displaced workers’ earnings losses. Our findings suggest that the conventional narrative about displacement – centred on average losses – obscures significant differences in how workers adjust after losing their jobs and masks the fact that roughly a quarter of displaced workers come out ahead after five years.

The Skewed Distribution of Earnings Losses

We examine workers displaced from all firm closures in West Germany between 2000 and 2005. Our analysis employs a novel combination of matching and synthetic control methods at the individual worker level, which enables us to capture the full distribution of displacement losses rather than just average effects.

Our central finding is that the distribution of earnings losses is highly skewed, meaning that focusing solely on average outcomes gives an incomplete and potentially misleading view of workers’ actual experiences. The large average losses documented in previous work are heavily influenced by a minority of workers who experience catastrophic earnings declines. In fact, the modal worker’s cumulative earnings loss over five years amounts to just three months of pre-closure earnings – a significant but manageable reduction. A relatively large number of displaced workers earn even more than comparable non-displaced workers following displacement. This finding is consistent with Farber’s (2017) finding that many displaced US workers quickly secure better-paying jobs.

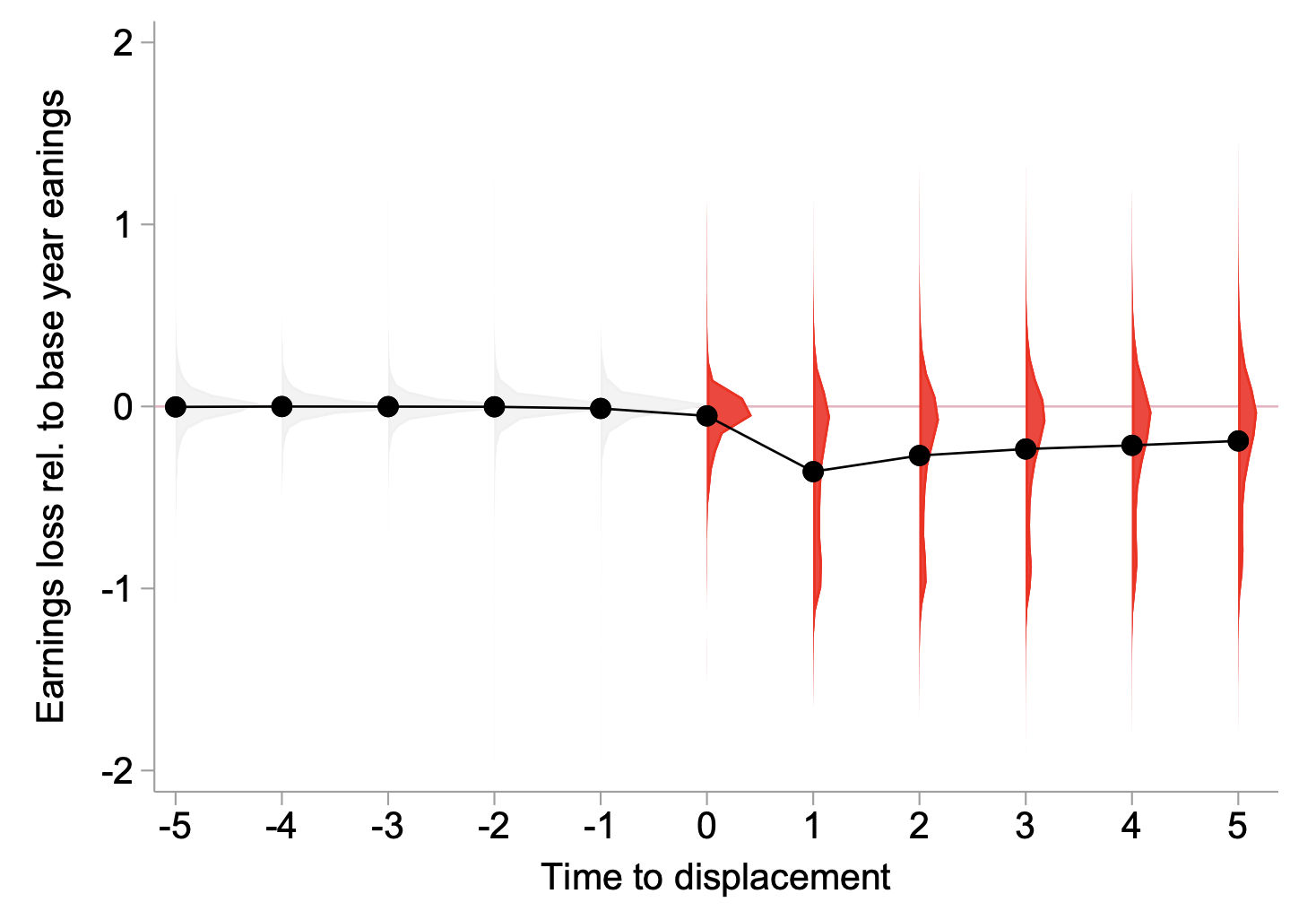

Figure 1 illustrates the point graphically; the dots plot mean earnings differences between displaced and a comparable group of non-displaced workers in the years before and after the displacement, while the grey/red shaded regions plot the full distributions. While the dots demonstrate a steep and persistent decline in earnings for the average displaced worker, the distribution of these losses is quite wide. Large losses are concentrated among a relatively small number of workers and many workers experience little disruption, or even earn more than would have been expected absent the displacement.

Figure 1 Distribution of relative earnings losses after firm closure

Notes: The figure displays the distribution of displaced workers’ earnings losses throughout a period of five years before until five years after a firm closure. The earnings losses are measured relative to the individual worker’s average earnings in the three years before the displacement. The dots represent the mean earnings losses for each period. The shaded areas represent the distribution of the displaced workers’ earnings loss estimates.

Source: IEB.

Limited Predictive Power of Observable Characteristics

Previous studies document differences in displacement effects for workers from different demographic groups – older workers, women, and those with lower educational attainment typically suffer larger average losses. This literature also highlights the loss of firm-specific wage premia as a primary driver of losses following displacement (e.g. Lachowska et al. 2020). Our findings align with these average patterns but also highlight their limited explanatory power: observable worker and firm characteristics explain less than 20% of the total variance in displaced workers’ earnings losses.

Even among displaced workers from the same firm, in identical roles, and with similar demographic characteristics, we find strikingly divergent outcomes. Some quickly transition to new employment with stable or even improved wages, while others face protracted unemployment or severe wage penalties. This within-group heterogeneity poses challenges for policymakers designing unemployment assistance programmes, as targeting based on worker or firm characteristics alone may fail to direct resources to those who most need them. Instead, ex ante unobservable factors and luck seem to drive a substantial portion of the heterogeneity in workers’ post-displacement outcomes.

Distinguishing ‘Adjusters’ From ‘Casualties’

To further illustrate the heterogeneity in displacement outcomes, we classify workers into two groups based on the severity of their losses: ‘adjusters’ (lowest quartile of losses) and ‘casualties’ (highest quartile of losses). Although these groups are similar demographically, their post-displacement labour market trajectories differ profoundly.

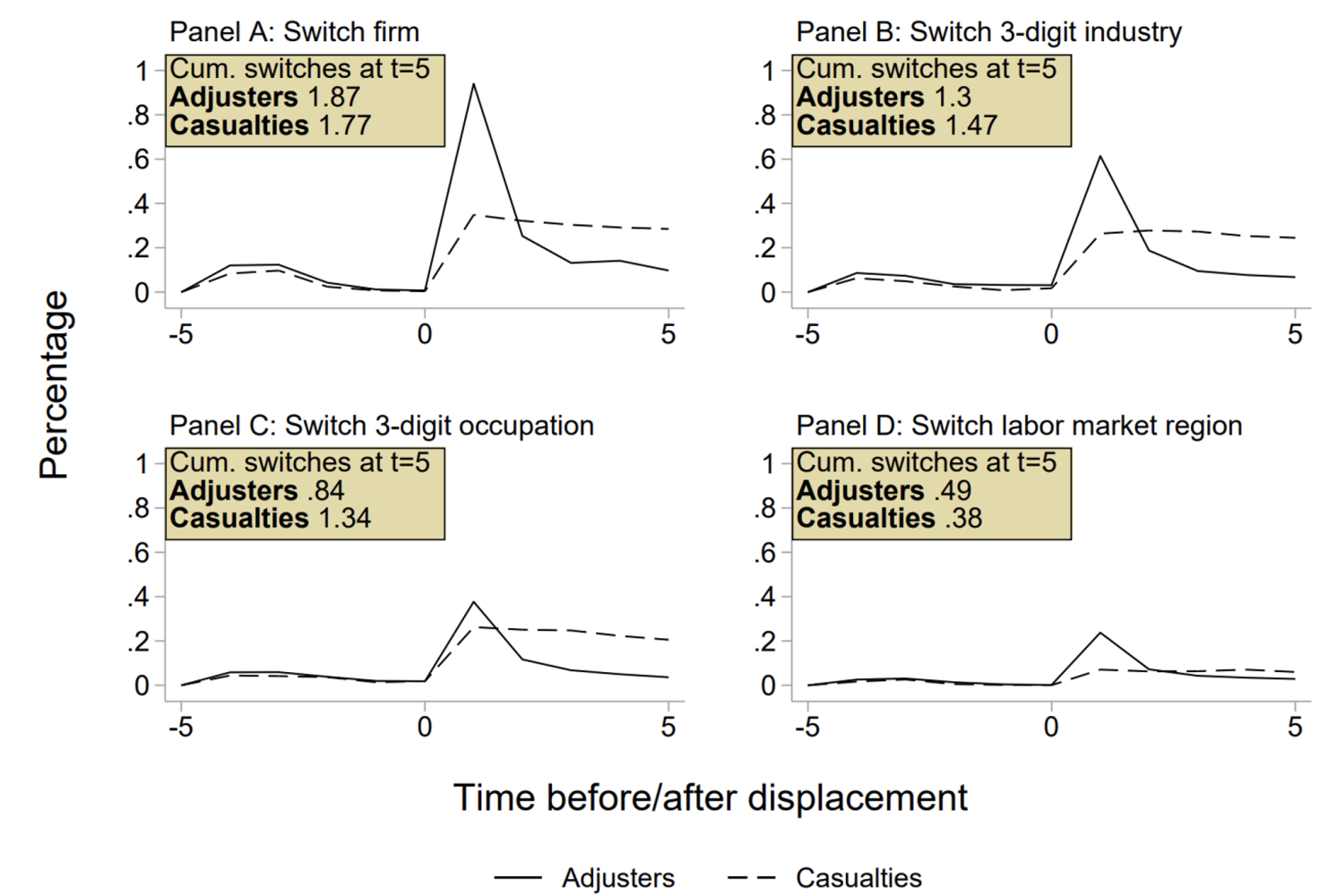

Adjusters react quickly. They switch occupations, industries, and even regions immediately after displacement. Adjusters stabilize quickly in these new positions and typically regain or exceed their pre-displacement wage levels within five years. In contrast, casualties struggle to regain stable employment, experiencing prolonged unemployment and unstable, low-paying jobs. Figure 2 documents this divergence across a variety of different margins of adjustment:

Figure 2 Fraction of workers who switch firm, industry, occupation, and region after firm closure

Notes: The figure compares the frequency of different margins of response to firm closure for Adjusters and Casualties around firm closures (time = 0). All changes are conditional on being employed during that year. The boxes in the upper-left corner summarize the average cumulative number of changes during the five-year period post-displacement for each group.

Source: IEB.

Interestingly, both groups exhibit similar overall mobility – changing industries, occupations, and regions multiple times – but adjusters make decisive moves immediately after displacement, while casualties experience delayed and unstable transitions. This finding echoes recent research by Fallick et al. (2025), who emphasise the role of extended unemployment spells in exacerbating displacement losses. Consistent with work by Minaya et al. (2023), we do not see large numbers of workers pursuing continuing education as a means of adjusting to the displacement.

The effect of firm-specific factors is also nuanced. Casualties go to lower paying firms and receive wages significantly below average in these firms. Adjusters go to slightly higher paying firms but then see wages significantly above the average worker in these firms.

Conclusion

Decades of research have confirmed that job displacement causes significant and persistent earnings losses. However, our new evidence suggests these losses are much more heterogeneous than previously documented. By focusing on average effects, researchers and policymakers may miss the substantial variation in displacement experiences among observably similar workers. Navigating a layoff involves personal circumstance, resilience, and luck. These unpredictable factors complicate the design of effective assistance programmes, as it remains difficult to anticipate who will adjust successfully and who will endure lasting disruption.

See original post for references

That depends. If you are part of the IG Metall covered labor aristocracy, you’re still very much golden (although even there, wage gains did not outpace inflation). The story of the last three decades has been premium industrial union members agreeing to a weakening of unions overall, as long as conditions for their own legacy contracts are kept stable. And within organizations like IGM or IGBCE (chemical/ utility sector) it’s about well-connected boomer members selling out younger ones.

The only German union left with a spine might the GDL (Union of German Train Drivers).

It’s all bog standard reductive economics where workers are mere footloose commodities.

What is missing from all this somewhat Panglossian worker mobility account where only the “casualties experience delayed and unstable transitions” is an acknowledgement, let alone recognition and study, of the range of human and social impacts that accompanies personal life disruption. Change for people usually involves more than a single metric.

Are new jobs within a commutable distance or do households need to migrate ?

How far ?

Is there increasing employment concentration spatially, with an increase in the number of economically depressed areas with growth in a few booming regions ?

How easy is intra-urban migration of unemployed persons ?

How much does it cost and how much do these costs displace increased pay for the “lucky” cohort ?

What are the knock on effects on transport and housing infrastructure ?

Historically, push factor dominated forced migration involved shifts of minimal distance, with people staying as close to their points of origin as possible (Ravenstein).

Has this pattern changed ?

Nothing in the numbers game played out in this research goes beyond the superficial.

Just using wage data ignores the wider economic and social costs and/or benefits of those personal and household disturbances that go with changing jobs in terms of disrupted family and social networks, schooling, costs of moving home, instability of new jobs, worsened conditions of work.

Where are the Midnight Cowboys ?

“…in terms of disrupted family…”

More specifically, how many more divorces were there? Financial issues is one of the primary drivers of failed marriages. Divorce is never free and the toll it takes on finances and savings are large.

There has been a lot of research on this going back decades – its well known that once people suffer unemployment over a significant amount of time (sometimes as little as 6 months), they become do some degree unemployable. This exacerbates regional employment problems when you have a very big layoff and it becomes almost impossible for those who want a job to get one. So you either subsidise employment to some degree, you provide help for people to move, or you just accept the social and economic cost, which so often leads to an underclass within struggling regional areas, which can be a generational struggle to improve. To what degree this is the ‘fault’ of the individuals or not is a value judgement.

When I was growing up in Ireland there was a very severe unemployment problem and there was definitely an element of some families refusing to allow themselves to fall into a bad set of life habits (one mother I knew used to insist on pulling her two unemployed sons out of bed at 7am every morning – and yes, eventually they both got jobs) while others just fall into what are perceived as bad lifestyle patterns (benefit hopping, petty crime, etc). Emigration of course was always an option for some, voluntary or otherwise. So much depends not just on the individual, but the set of options available to them, especially when it comes to mobility.

So I’m not really sure this study says anything particularly new, except that economists always love to claim insights into topics that other social sciences have been studying for years. Its not an easy topic as there are so many hidden value judgements at work (assuming that some people are just lazy, or that everyone wants to work, or that there is something inherently wrong with people choosing to live on welfare if available). It also ignores the various hidden factors in economic figures – the degree, for example, that unemployed people may have long term disabilities (or that people on disability pay are in fact just long term unemployed), or that people are working off official books, or whatever. Even quite subtle differences in welfare/education rules can significantly skew the ‘official’ unemployment rate, or indeed, impact on peoples response to unemployment.

Personally speaking someone else’s job loss means the country may be nearing or in a recession, or perhaps it is industry specific. Think here of South Carolina and the departure of the textile industry and as well North Carolina and the shift away from manufacturing by the furniture industry. If your profession just prior to this taking place circa 1980’s to middle 1990’s, those jobs were just never going to return or if they happen to return, it’s within an umbrella corporation holding group owned by a buyout firm. Prospects diminish greatly during the interim.

To repeat myself I lost twice inside of roughly 3 ish years. Your appeal as a potential hire for an employer begins to fade in the twilight the longer the career employment gap shows. I’m not one to lie or gloss over what the reality was at the time; being unemployed during much of 2010, it was truly unnerving the extended lapse to find gainful employment in the finance industry again. Residential servicing companies were a consistent target as the GFC continued to unfold but alas no dice.

People with the glad handing or simple wave of the hand that these are mere hurdles just don’t comprehend the fall out and as well how really uneven outcomes were after the entire TARP action to provide a softer landing spot and even further, or as well just how much the FDIC extended in temporary guarantees to financial firms’ corporate bond debt issuance. Funny enough I still keep emails detailing some of these actions to save important institutions.

Going long I acknowledge. I landed two jobs eventually, first in November of 2010 which ended by April 2012. Second role was started in July 2012. Prior to 2008, if my level of income had been driving my happiness in life I faced some harsh realities that individuals working at Citigroup, by example, just never experienced at an absolute trough in the US economy. Jobless recovery was really what it was.

I was curious as to the Farber reference in the paper which states:

Farber’s (2017) finding that many displaced US workers quickly secure better-paying jobs.

Anecdotally, this seems at odds with most anecdotal data. I wasn’t able to access the full Farber paper but the abstract isn’t as positive as the reference in the paper (excerpt of abstract):

These data show a record high rate of job loss in the Great Recession, with almost one in six workers reporting having lost a job in the 2007-2009 period, that slowly returned to pre-recession levels in the 2011-2015 period. The employment consequences of job loss are also very serious during this period with very low rates of reemployment and difficulty finding full-time employment during the Great Recession and its aftermath. The reduction in weekly earnings for those full-time job losers during the 2007-2015 period who were able to find new full-time employment are relatively small, even for those displaced since 2008. In fact, a substantial minority of these job losers report earning more on their new job than on the lost job.

I wouldn’t conclude that “a minority….reported earning more on their new job” as the same as “many displaced US workers quickly secure better-paying jobs” , particularly when the original paper cites, “difficulty finding full-time employment”.

Anecdotal experience from my professional network is that generally once an individual loses their position in the corporate hierarchy it is exceptionally difficult to gain an equivalent position, let alone a higher paying one. Factor in age and it’s nearly an impossibility.