Consider the new through-the-looking-glass world of banking crises circa 2016: bankers are now actively stoking fears so as to force officials to give bailouts.

In 2008, wobbly banks were all doing their utmost to persuade their counterparties and Mr. Market that they were just fine. Remember how monolines fruitlessly told analysts that their insurance contracts were drafted so that they didn’t have to post collateral and it would be decades before they’d have to settle up on the losses on their subprime guarantees? How about the crisis poster child Lehman, which spent months insisting that short seller David Einhorn was all wet? Lehman not only engaged in bogus accounting on a mass scale (its Repo 105 was the biggest single item, but it was also posting impossibly optimistic valuations on California commercial real estate ventures Archstone and SunCal), it even managed to stick JP Morgan with collateral so rancid that Lehman staffers called it “goat poo”. And mind you, even though Goldman Sachs was madly squeezing AIG for as much cash as it could extract, Lloyd Blankfein was not broadcasting to reporters that AIG or other major financial firms were on the ropes.

By contrast, we now have senior bank executives pushing the story that Italian banks, and now from Deutsche Bank’s chief economist, large European banks generally, are in bad shape. This is hardly news to anyone who has been paying attention. Big European financial firms went into the crisis with lower equity levels on average than their US counterparts. European officials also did less than Americans did to press their charges to clean up (the FDIC forced Citigroup to downsize considerably, for instance). American regulators were more insistent about having banks boost their capital levels.

Moreover, even though US growth has been lackluster, Europe has teetered on the verge of contraction. That means a worse environment for bank profits even before you get to the impact of zero and increasingly negative interest rates. Normally, the first line of defense for a company to improve its equity levels is retained earnings. That’s not a promising source for many European banks.

So why are prominent banking figures, contrary to the time-honored practice of talking up the Confidence Fairy, conveying bad news to the degree that it looks like they are trying to spook investors? This is what Bini Smaghi, the chairman of Societe Generale, said last week:

Italy’s banking crisis could spread to the rest of Europe, and rules limiting state aid to lenders should be reconsidered to prevent greater upheaval, Societe Generale SA Chairman Lorenzo Bini Smaghi said.

“The whole banking market is under pressure,” the former European Central Bank executive board member said in an interview with Bloomberg Television on Wednesday. “We adopted rules on public money; these rules must be assessed in a market that has a potential crisis to decide whether some suspension needs to be applied.”

And over the weekend, Deutsche Bank’s chief economist, David Folkerts-Landau, told Die Zeit that Europe needed a TARP-style rescue program for its banks. The Google Translate English rendition (see original here):

The chief economist of Deutsche Bank calls a multibillion dollar bailout for European banks. The institutions should be equipped American-style with fresh capital. At that time the government had stepped in 475 billion dollars. “In Europe, the program must not be so large. With 150 billion euros can be European banks recapitalize,” said David Folkerts-Landau…

The decline in bank stocks is only the symptom of a much larger problem, namely a fatal combination of low growth, high debt and a proximity to dangerous deflation. “Europe is seriously ill and needs to address very quickly the existing problems, or face an accident,” said the chief economist.

Brexit worries have forced what is commonly called a recognition event. And the only way to escape an untested, Rube Goldberg EU-wide scheme for dealing with sick banks is to create a real crisis so that the authorities can break glass and do something else….like bailouts or nationalizations. Folkerts-Landau is explicit in making a case against bail-ins, which wipe out shareholders and next bondholders, working up from the most junior to the most senior. While that ordinarily sounds like a fine idea (after all, these are supposed to be sophisticated investors who signed up to provide risk capital), in Italy, as also happened on a large-scale basis in Spain, depositors were persuaded by bank employees to buy other instruments, in the Italian case bonds, and were falsely told they were just as safe as deposits. From the Financial Times in February:

Pressure on the central bank rose in November after the rescue of four small regional banks in central Italy dealt big losses to thousands of retail investors as a result of new EU requirements on how to manage bank failures.

And the savers’ exposure is large. This article (in Italian) estimates it at €60 billion, which is larger than the €40 billion estimated size of an Italian bank rescue. Note that it also points out that most of these bond sales were fraudulent. And the priceless part? Italian economist Thomas Fazi believes this pilfering of depositors started when ex-Goldman banker Mario Draghi was head of the Bank of Italy.

Keep in mind that if small savers take a bath, it will lead to greater damage to the Italian economy…which will lead to more loans going bad, which will lead to more savers being forced to contribute to bail-ins, which will lead to yet more loan losses.

It’s not that the condition of banks has suddenly taken a turn for the worse, but that fear of a Brexit has cut off the most plausible escape routes for the banks ex the goner Italian banks to get out of their mess, which is selling shares to the public.

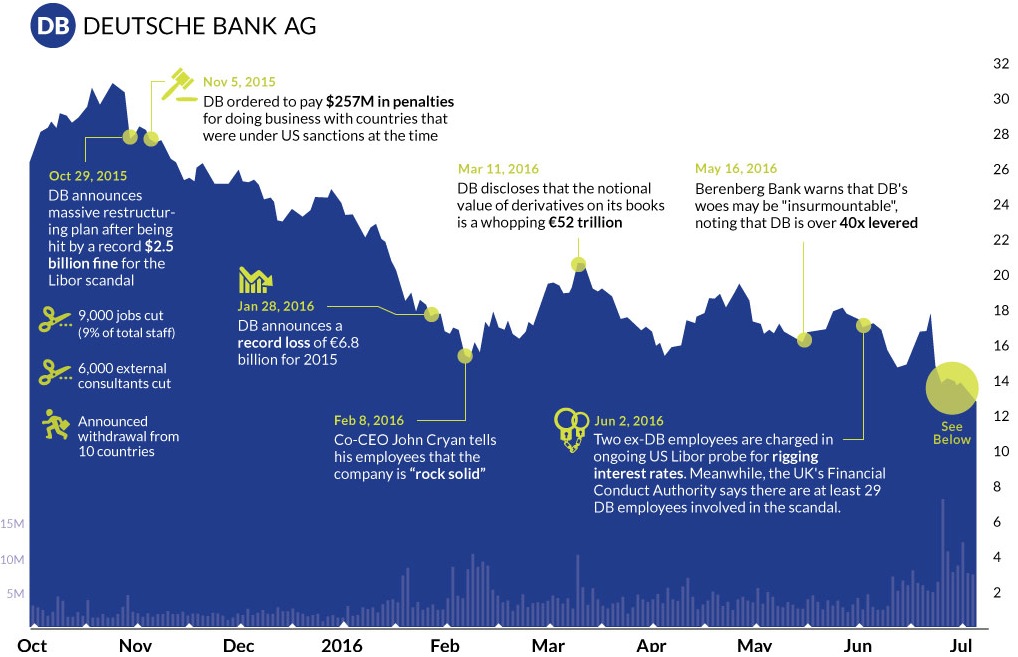

Banks stocks have taken a big hit since the Brexit vote, and those of the weakest megabank, Deutsche, See this chart from the Visual Capitalst and note the decay from late June:

As we wrote last week, Italy has been trying to persuade European officials to allow it to sidestep bail-in rules that are part of the new EU-wide banking regime that came into effect in January. As we pointed out, perversely, Italian banks have been to a large degree a victim of the crisis itself, as opposed to pre-criss recklessness. They have seen non-performing loans rise as a result of the direct damage of the sharp contraction in the economy and the protracted malaise. They also managed to wrong-foot the post crisis era, failing to do enough to boost bank capital levels, either though state aid or forcing them to sell equity.

Italian premier Matteo Renzi, having failed early in the year to get a waiver so as to allow Italy to provide an estimated €40 billion to a good bank/bad bank scheme (the sort used successfully in the US savings & loan and in Sweden’s early 1990s banking crises), made a personal appeal to Merkel in the wake of the Brexit upheaval and was again rebuffed. From the Financial Times on June 27:

Brussels has in the past warned Italy that there are no signs of crisis threatening financial stability. It has also argued that a capital injection would fall foul of the new bail-in rules in the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive.

“Germany would be out of its mind to be sharing sovereignty and risk with a country that behaves in this manner,” said one senior European official involved in debate over Italian banks. The official called Italy’s attempted exploitation of the Brexit situation “cynical”.

If you read between the lines, you can see that the Eurocrats are sticking firmly to their playbook, despite the fact that many experts deem it to be a train wreck in the making. If you read the section that describes emergency powers (Article 56 on p. 98), you can see it allows their use only in very limited circumstances. And if you track back the references to other sections of the directive, you can see its insistence that private sector options like bail-ins be exhausted before public monies are deployed.

So with this background, it becomes more obvious what Bini Smaghi and David Folkerts-Landau are up to. Deutsche Bank is next in line if the Italian banks start falling over or the bail-in start. The Financial Times last Friday described why the bank shares (and its co-co bonds, which would be converted to equity if certain triggers are met) have gone south in a very major way. Key points:

Deutsche Bank has had a difficult 10 days. Last week, one of its US businesses failed a Federal Reserve stress test for the second year running. Seven days ago, the International Monetary Fund called it “the most important net contributor to systemic risks” of the world’s big banks. Its shares on Friday — which have suffered violent swings all year — hit an all-time low…

In recent days, it is Deutsche’s trading business that has attracted most attention. Matteo Renzi, Italy’s prime minister, on Wednesday claimed — in an intervention read by some as a swipe at Deutsche — that Italy’s wobbly banks were less of a headache than “the question of derivatives at other banks, at big banks”.

Rival bankers often make similar points, raising concerns about Deutsche’s large stock of “level 3” assets, which are so illiquid that they cannot be valued based on market prices….the assets are worth some 70 per cent of Deutsche’s total common equity — a lower level than at Barclays and Credit Suisse, but higher than at Deutsche’s US rivals, JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley…

Yet despite rival bankers’ focus on these more exotic assets, analysts and investors say the biggest challenges for the bank are more prosaic.

“The problem for Deutsche is that they have weak revenues, they have a lot of litigation hanging over them, and they have weak capital,” says one of the bank’s 20 biggest investors.

Translation: there is very little to like. The article also says the best course available for Deustche is to sell assets. But that’s merely the best of bad options. Generally, distressed companies wind up selling their stronger businesses when they are desperate, leaving an even weaker remaining enterprise. And given the worries in the banking industry, it’s not as if the German behemoth is likely to fetch good prices.

Let us return to Folkerts-Landau’s rescue sales pitch. The subhead of the story reads: “Private creditors should not participate.” The Deutsche bank economist argues that the bail-ins will do more harm than good. And even if you agree with the premise that bond fide bond investors should take a hit, as opposed to Italian depositors that were snookered, the one-size-fits-all bail-in rules don’t allow for such surgical distinctions.

Now I am sure Folkerts-Landau, if challenged, would deny that his warning about the need for a broader European bank rescue applies first and foremost to his employer, Deutsche Bank. But even if he actually believes his own PR, it is not hard to see the implications of his stark warning.

So the Renzi/bank executive view is leagues apart from where Merkel, her finance minister Wolfgang Schauble, and banking authorities are. They appear unwilling even to consider that their shiny new rules toy bail-in regime will blow up in their first large-scale use, and that their prized Deutsche Bank is likely to be part of the collateral damage. They are treating Renzi’s pleas as whinging, as opposed to a better course of action than the default path.

Given the German fixation with rules and Brussels’ inability to admit error, we are now in a race of sorts. Will market professionals succeed in creating the perception that a disaster at Deutsche, which is clearly too big to fail, is imminent, and thus force the Eurocrats’ hand? Deustche’s share price now €11.74; some experts think a drop below €10m would put regulators on high alert. Or will the Italian banks instead be forced into bail-ins and produce a slow-motion unraveling across Europe? Stay tuned.

“…a disaster at Deutsche, which is clearly too big to fail, is imminent …”

The root issue which MUST be addressed is TBTF.

How about if we MUST not follow existing rules … we create some new rules that address TBTF.

And … if we are going to bail out people … we can in fact bail out select people.

Italian peons are an easy group to bail out. The 1%? Let them eat cake.

The fallacy of the false dilemma.

Door number 3, please Vanna.

I saw Folkerts-Landau on Bloomberg Surveillance last week, and my primary take away recollection is that he thinks the concept of bail-ins is completely looney. I realize he is talking his book, but I thought at the time ‘…at last, someone sees the catastrophe on the doorstep…’.

I don’t envy Mr. Folkerts-Landau’s job, but it seems pretty astonishing that Schauble and the Eurocrats and not even listening to what he is saying. My visual would be the robot in ‘Lost in Space’ bleating ‘Warning! Danger Will Robinson!’

Warning! Warning! Herr Schauble!

It’s a hard life being a banker, you are allowed to create money out of nothing; you have no manufacturing, supply and distribution chains to worry about, all you have to do is loan money to people that can pay you back.

Somehow they never seem to get the hang of it.

Bankers only have one job to do and they can’t do it.

What are bankers like at prudent lending?

“What is wrong with lending more money into real estate?” Australian, Canadian, Swedish, Dutch and Hong Kong bankers now

“What is wrong with lending more money into the Chinese stock market?” Chinese banker last year

“What is wrong with lending more money into real estate?” Chinese banker pre-2104

“What is wrong with lending more money to Greece?” European banker pre-2010

“What is wrong with a NINA (no income, no asset) mortgage?” US banker pre-2008

“What is wrong with lending more money into real estate?” US banker pre-2008

“What is wrong with lending more money into real estate?” Irish banker pre-2008

“What is wrong with lending more money into real estate?” Spanish banker pre-2008

“What is wrong with lending more money into real estate?” Japanese banker pre-1989

“What is wrong with lending more money into real estate?” UK banker pre-1989

“What is wrong with lending more money into the US stock market?” US banker pre-1929

Globally incompetent at the only job they have to do.

Debt has been around for 5,000 years but today’s bankers still haven’t got the hang of it.

You can imagine what their complex derivatives are like.

And then I looked at an article in the WSJ on Tuesday, entitled “Loan Market Pulls Back.”

Excerpts:

“The pullback was triggered bt the investor flight from riskier types of bonds…..one contributing factor is a regulation that will require producers to hold some of the securities they create, a requirement that makes the business less profitable….”

So, when the dogs are force-fed the shit they create, they won’t eat it. Surprise, surprise.

What a good idea.

Not popular with the bankers I expect.

The answer to the question, I think, is in the piece. Bankers in Europe are making a fuss in a slightly different way than bankers in the US because the latter didn’t have to. The US political class already wanted to bail them out, so they could play it cool.

In Europe, however, there is at least some pushback against just handing over yet more bailouts to the banksters. That means banksters have to do the dirty work directly. It’s not that complicated really.

That’s the answer. Banks are making a fuss because they want people acting as self-interested depositors and creditors and shareholders and so forth rather than as taxpayers and citizens and so forth advocating consistent moral and ethical principles. Bail ins are no worse than bail outs. It’s all just a game of arguing about who should eat the losses. Nothing fancier or more high brow than that.

This is different in the US because the east coast financial regime could force the rest of the country to pay for the bailouts rather easily. EU states have more autonomy. Sometimes federalism is nice. Sometimes it sucks. Welcome to the world of tradeoffs.

I so hope you’re right. The austerity-driven bail-outs have put us on the brink of collapse. Hopefully someone is listening.

Is that ‘austerity-driven bailouts’ or ‘austerity-driving bailouts?’

That is, is

1, Bailouts lead to austerity

or

2, Austerity leads to bailouts?

Well, bail-outs lead to austerity, i.e. the motivation behind austerity in the eurozone is bailing out banks with taxpayer money. But it is a vicious cycle so, both of those definitions are true.

The ballot not the bailout!

Ha, yes indeed. Interesting how close those two are.

Am I the loony here, or is this concept of widespread ‘bail ins’ the perfect recruiting mechanism for populist political movements, from the Right or Left inclusive?

No. Yes.

“The paper holds their folded faces to the floor

And every day the paper boy brings more.”

So will they retroactively reverse the Cyprus bail-in if this goes through and the big Euro banks get bail-outs? Why is what’s good for the goose not good for the gander? Admittedly, it was horrible for the goose, but still….

There nothing wrong with a “tax payer” financed bailout, as opposed to the lunatic Rube Goldberg bail-in scheme the Eurocrats have devised. The thing is that injecting public funds amounts to a public receivership, i.e. nationalization, if properly done, with the CEOs and boards fired, shareholders wiped out, together with most bonds and any residual ownership claims only attaching to the bad bank of non-performing assets. That is by far the most efficient and equitable way to resolve insolvent banks. But that would be “socialism”, acting in the public interest against neo-liberal dogma, which would make Mr. Market sad. So are these banksters really asking for someone to please shoot them, to put them out of their misery?

I would GLADLY accommodate that should anyone decide that “we” (as a collective whole) should euthanize the bankers. Although, my method would not be humane.

if the banks get another bailout it’s going to lead to a political crisis. in italy, at least, they have M5S waiting in the wings so maybe it wouldn’t be all bad, but in France, it would be Le Pen.

Another bailout and the austerity and cuts to social security that would require under Euro rules would have to create massive upheaval. Anything else would be unfathomable.

I beg to differ.

The bail-ins would cause a political crisis because small depositors who were persuaded to buy bonds and told they were the same as deposits will lose all that money.

The sort of “good bank/bad bank” bailout that Renzi is trying to get the EU to let him do won’t. The banks will wind up being smaller and one assumes many will have significant changes forced on them

You also forget that these banks really are Italy’s backbone. They do real economy lending. They are not like Citigroup or Deutsche, with far-flung international operations, lots of speculative trading, and obscenely well paid investment bankers.

I hear your point, but how can you say that those poor small depositors got defrauded and then also say the banks do real economy lending? It can’t be that the loans were risky and that the loans were not risky. Either people lending money to the banks knew what they were doing, or they were systematically preyed upon by the banks. There is no scenario in which both parties are innocent victims.

Renzi isn’t just trying to set up a good bank/bad bank system. He’s trying to get the rest of the eurozone to help pay the costs. If he was raising the funds domestically, this wouldn’t be an issue. The Italian government could simply reimburse the first, say, 10,000 euros lost to a bail-in by any Italian citizen.

And more broadly, if we are saying that individuals are incompetent at making decisions about how to deploy their money, then that indicts the entire concept of property rights.

i agree that bail-ins would cause a political crisis, absolutely. but, in my opinion, so would another no-strings-attached bailout. the only good way to handle it would be a nationalisation coupled with prosecutions.

Couple of points:

1) Merkel knows exactly what she’s doing in taking a hard stance against Italy. She’s just cynical enough to know that she can get away with that, and then do a 180 when it’s Deutsche’s turn. Draghi, despite being an Italian who’s responsible for the Italian mess, will go along. Rules after all, are for little people and little PIIGS. Witness the move to sanction Spain and Portugal for their fiscal deficits while leaving much bigger violators like France untouched.

2) I hate it when small savers are used as a human shield to protect much larger interests. If we’re going to break the sanctity of contracts and the rule of law (both of which require the banks to go bankrupt), let’s do it right: have the govt. selectively buy back at par any bank bonds owned by people with < $100k invested, and let the rest of the investors sell their bonds at whatever price they fetch in the open market and/or bankruptcy court. This wouldn't even break any law: the government is merely setting terms on its buyback policy. This, BTW, is what the US govt should have done with the monolines who were threatening that municipalities would take the hit if they weren't bailed out: the Govt. should have provided a one-time Fed-backed guarantee for all muni's insured by the monolines, and then let the monolines die.

3) This sounds like a stupid question but isn't: why does everyone on Wall St. think Lehman was such a disaster? I understand all of the world's finance industry had a near-death experience. But *it didn't die*. As scary as it was, the world made it through. And for those of us living on Main St. It was hardly an event worth even remembering. And I say this as a Main St'er who understands the turmoil Lehman caused on Wall St (thanks to your site's coverage during those days! :-)

Quite frankly, Lehman was the *only* Federal response that I supported: they went bankrupt, and any danger to the markets was addressed and resolved without too much pain to Main Street. I understand that Wall St. thinks it's sheer luck we all survived, but I don't think so. I think Lehman's importance to Main St (like all of Wall St) was much less than they like to think. And even the incompetents running the Fed and Treasury managed to do what was needed to firewall it from the rest of the world.

Wall St's sense of self-importance is such that they probably believe the Sun won't rise unless Lloyd Blankfein summons it every morning. But the truth is the rest of the world did fine the day Lehman went bankrupt (understandably, with a lot of stuff being managed behind the scenes), and the sun continues to rise despite 3 "TBTF" banks actually failing (Bear, Lehman, Merrill).

I hate that the "memory of Lehman" has become the finance world's equivalent of the Holocaust, with their frequent chants of "never again, never again" serving as a convenient threat to extract more bailouts. I say, let Deutsche fail. If that takes the rest of Wall St. with it, even better. The lesson of Lehman shouldn't have been that we can't let a bank fail, it should be that it's indeed possible to manage a disorderly unwind of a global trading book.

Couldn’t agree more.

Huh? The Lehman bailout triggered a series of rescues that amounted to the biggest looting of the public purse in history. The cost of ZIRP alone is over $300 billion a year to savers and retirees. It was so obvious that Simon Johnson called it the “quiet coup” shortly after it happened, in May 2009.

Moreover, you ignore the second bailout, which was the 2012 National Mortgage Settlement, and the fact that it validated and institutionalized servicing abuses, which in turn led to millions of foreclosures which could and should have been averted. This was inefficient looting, since the servicers got fees of a few thousands of dollars to at most a bit over $10,0000, while the losses to homeowners who could have been salvaged and mortgage investors was vastly more than that.

And those foreclosures then set up the acquisition of those homes by private equity and the abuses we’ve documented on that front.

And I similarly do not agree with the “Merkel has this all figured out”. The Germans are in denial as to how utterly unworkable their bank resolution rules are. Merkel is also in a precarious position as a result of her mishandling of the refugee crisis. The German parliament is opposed to stealth monetization (not that they have a vote but Merkel is already in danger of losing her Chancellorship, and having failed to protect German taxpayers from a Deutsche rescue could be the step that pushes them to act) and a German bail out under the banking rules will have to be a fiscal operation.

Plus the Europeans generally were very slow to act on their crisis last time around. There’s no sign they are any more on top of things now than then. And the leadership (unlike then) is distracted by Brexit, the refugee crisis, and the US/NATO escalating with Russia.

In other words:

1. Merkel has not thought this through. Renzi has now cited two separate exceptions under the new banking directives which would allow him to bail out the banks. This would be a domestic fiscal operation and not hugely controversial in Germany.

2. By contrast, if Renzi starts doing bail-ins, Deutsche will soon come under massive market pressure and need to be rescued. And it greatly increases the odds that 5 Stars will be able to force elections. If they win, which again would be likely, they would have a referendum on leaving the Eurozone. Recent poll data suggests it would prevail. That goes 180 degrees against Merkel’s top priority, which is keeping the EU/Eurozone intact.

3. Merkel and Schauble seem to be giving undue weight to the opinions of parties in Brussels, who refuse to see how destructive the bail-in rules are, and may also be acting out of prejudice against the periphery countries.

Yves,

Thanks for the reply. I guess it’s a game of “what if”, but I’d assert that the bailouts / fallout from Lehman’s bankruptcy would have happened regardless of whether Lehman itself was saved. Indeed, I’d actually go further: once the government basically said there would be no further Lehman’s, banks were emboldened to push harder for better bailout terms because they knew the govt wouldn’t call their bluff and let them go BK. It’s the equivalent of holding a gun to your head and threatening to shoot unless you get your way: as long as you know the other party would never let you pull the trigger, there’s no reason to not make outrageous demands.

The biggest looting of the public purse was in order to bail out *the other banks* that survived. For example, Goldman Sachs getting paid back at par on the CDS they held from AIG, or JPMorgan being given Bear Stearns with the government on the hook for most of the losses (JPM of course could keep any profits from those assets). Are you arguing that if we only kept Lehman alive we wouldn’t have had to bail out Goldman Sachs? Or gift Bear Stearns to JPM?

Similarly for the second bailout you mentioned, I don’t see a connection to the Lehman BK (maybe I’ll have to read further about it). Rather, TBTF banks, emboldened by knowing that the government would never let them die, used their newfound leverage to skirt the laws. The argument for brushing aside laws regarding servicer abuses was that if all those mortgages were voided or tied up in court, the banks holding them would… end up like Lehman, and we can’t have that. IOW, the threat of “another Lehman” was trotted out to prevent banks from facing the consequences of their actions.

My point isn’t that a disorderly unwind of a massive, global, opaque trading book is a great thing for this world. It’s that it’s survivable, and if the choice is between doing that and allowing a bank to go under (thereby preserving that threat for other banks), vs. caving and bailing out a bank because we’re so afraid of a disorderly unwind, then I’d choose the former: despite the short-term pain, in the long-run, preserving the threat of a bankruptcy helps keep banks in line in the future (of course, jail terms would do that job even better, but those are apparently also off the table).

If your argument is that no, actually, a disorderly unwind does much more damage long term than a bailout, fine. But, IMHO, that just means we should take over a bank even earlier: when there’s still time for a reasonably orderly unwind. If the consequences of DB failing are akin to an asteroid hitting the Earth, then EU banking regulators should take over and begin dismantling their trading book now, not wait for a time when the unwind will be even harder.

DB is de facto insolvent. It has been for at least a couple of years. This is not a secret (just look at its share price and CoCo bonds). It will be de jure insolvent in another year or two when the EU’s timeline for increased capital reserve requirements meets DB’s ongoing losses. If a disorderly unwind is indeed so bad, why should we not take over now, while there’s still a little time to mitigate that disorder?

One the several definitions of deflation is: excessive output over demand.

The bank oligarchs are the ones who refuse to admit that exists excessive capacity in the financial services. Putting aside the fact that the so called Fintech will erode much more this financial sector.

They do not admit that exists excessive financial services and banks in the western economies. They do not admit that even debt has some constraints and can not rise ad aeternum. Just because the level of the systemic risk!

As they do not admit and they do not want to cut excessive capacity output they are trying to scare the people and influence weak politicians. But no matter what they will get, several banks will fail and will be closed just because exists too much banks and financial services for the current demand.

Who will blink first? The maket will impose them the good solution. Cut the excessive output for the weak demand.

Ciao

Italian bank problems not an “acute crisis” – Dijsselbloem

http://www.reuters.com/article/eurozone-italy-banks-dijsselbloem-idUSB5N18F003

The German Finance Minister agrees and it is becoming more tough against the bank oligarchs:

https://www.neweurope.eu/article/deutsche-bank-not-share-german-government-views-banking-bailouts/

Outside Europe just a few are understanding what is going on. Bank oligarchs beg for money from tax savers and Germany refuses to pay the bill. The pattern is clear from the beginning specially after the Greek example.

This time it seems that the bank oligarchs will bite the bullet.

Ciao