Yves here. Get a cup of coffee. This is clearheaded, meaty treatment of a pervasive distortion in economic and popular discourse.

By Dirk Bezemer, a professor of economics at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands and Michael Hudson, a distinguished research professor of economics at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, and a professor at Peking University. Originally published at the Journal of Economic Issues; 50 (2016: #3), pp. 745-768. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2016.1210384; cross-posted from michael-hudson.com

Abstract: Conflation of real capital with finance capital is at the heart of current misunderstandings of economic crisis and recession. We ground this distinction in the classical analysis of rent and the difference between productive and unproductive credit. We then apply it to current conditions, in which household credit — especially mortgage credit — is the premier form of unproductive credit. This is supported by an institutional analysis of postwar U.S. development and a review of quantitative empirical research across many countries. Finally, we discuss contemporary consequences of the financial sector’s malformation and overdevelopment.

Keywords: capital, credit, crisis, rent

Why have economies polarized so sharply since the 1980s, and especially since the 2008 crisis? How did we get so indebted without real wage and living standards rising, while cities, states, and entire nations are falling into default? Only when we answer these questions can we formulate policies to extract ourselves from the current debt crises. There is widespread sentiment that this crisis is fundamental, and that we cannot simply “go back to normal.” But deep confusion remains over the theoretical framework that should guide analysis of the post-bubble economy.

The last quarter century’s macro-monetary management, and the theory and ideology that underpinned it, was lauded by leading macroeconomists asserting that “The State of Macro[economics] is Good” (Blanchard 2008, 1). Oliver Blanchard, Ben Bernanke, Gordon Brown, and others credited their own monetary policies for the remarkably low inflation and stable growth of what they called the “Great Moderation” (Bernanke 2004), and proclaimed the “end of boom and bust,” as Gordon Brown did in 2007. But it was precisely this period from the mid-1980s to 2007 that saw the fastest and most corrosive inflation in real estate, stocks, and bonds since World War II.

Nearly all this asset-price inflation was debt-leveraged. Money and credit were not spent on tangible capital investment to produce goods and non-financial services, and did not raise wage levels. The traditional monetary tautology MV=PT, which excludes assets and their prices, is irrelevant to this process. Current cutting-edge macroeconomic models since the 1980s do not include credit, debt, or a financial sector (King 2012; Sbordone et al. 2010), and are equally unhelpful. They are the models of those who “did not see it coming” (Bezemer 2010, 676).

In this article, we present the building blocks for an alternative. This will be based on our scholarly work over the last few years, standing on the shoulders of such giants as John Stuart Mill, Joseph Schumpeter, and Hyman Minsky.

Immoderate debt creation was behind that “Great Moderation” (Grydaki and Bezemer 2013). That is what made this economy the “Great Polarization” between creditors and debtors. This financial expansion took the form more of rent extraction than of profits on production (Bezemer and Hudson 2012) — a fact missed in most analyses today (for a proposal, see Kanbur and Stiglitz 2015). This blind spot results from the fact that balance sheets, credit, and debt are missing from today’s models.

The credit crisis and recession are, therefore, a true paradigm test for economics (Bezemer 2011, 2012a, 2012b). We can only hope to understand crisis and recession by developing models that incorporate credit, debt, and the financial sector (Bezemer 2010; Bezemer and Hudson 2012). Here we provide the conceptual underpinning for this claim.

To explain the evolution and distribution of wealth and debt in today’s global economy, it is necessary to drop the traditional assumption that the banking system’s major role is to provide credit to finance tangible capital investment in new means of production. Banks mainly finance the purchase and transfer of property and financial assets already in place.

This distinction between funding “real” versus “financial” capital and real estate implies a “functional differentiation of credit” (Bezemer 2014, 935), which was central to the work of Karl Marx, John Maynard Keynes, and Schumpeter. Since the 1980s, the economy has been in a long cycle in which increasing bank credit has inflated prices for real estate, stocks, and bonds, leading borrowers to hope that capital gains will continue. Speculation gains momentum — on credit, so that debts rise almost as rapidly as asset valuations.

When the financial bubble bursts, negative equity spreads as asset prices fall below the mortgages, bonds, and bank loans attached to the property. We are still in the unwinding of the biggest bust yet. This collapse is the inevitable final stage of the “Great Moderation.”

The financial system determines what kind of industrial management an economy will have. Corporate managers, as well as money managers and funds, seek mainly to produce financial returns for themselves, their owners, and their creditors. The main objective is to generate capital gains by using earnings for stock buybacks and paying them out as dividends (Hudson 2015a, 2015b), while squeezing out higher profits by downsizing and outsourcing labor, and cutting back projects with long lead times. Leveraged buyouts raise the break-even cost of doing business, leaving the economy debt-ridden. Profits are used to pay interest, not to reinvest in tangible new capital formation or hiring. In due course, the threat of bankruptcy is used to wipe out or renegotiate pension plans, and to shift losses onto consumers and labor.

This financial short-termism is not the kind of planning that a government would undertake if its aim were to make economies more competitive by lowering the price of production. It is not the way to achieve full employment, rising living standards, or an egalitarian middle-class society.

To explain how the bubble economy’s debt creation leads to debt deflation, we distinguish between two sets of dynamics: current production and consumption (GDP), and the Finance, Insurance and Real Estate (FIRE) sector. The latter is associated primarily with the acquisition and transfer of real estate, financial securities, and other assets. Our aim is to distinguish this financialized “wealth” sector — the balance sheet of assets and debts — from the “real” economy’s flow of credit, income, and expenses for current production and consumption.

In the next section, we state our case, distinguishing the financial sector from the rest of the economy, and rent from other income. It is as if there are “two economies,” which are usually conflated. They must be analyzed as separate but interacting systems, with real estate assets and household mortgage debt at the center of the bubble economy. In section three, therefore, we examine the significance of household debt. In today’s “rentier economy” this represents not real wealth, but a debt overhead. In section four, we discuss the pathologies arising from this overhead: loss of productivity and investment, with rising inequality and volatility.

Finance Is Not The Economy; Rent Is Not Income

Analysis of private sector spending, banking, and debt falls broadly into two approaches. One focuses on production and consumption of current goods and services, and the payments involved in this process. Our approach views the economy as a symbiosis of this production and consumption with banking, real estate, and natural resources or monopolies. These rent-extracting sectors are largely institutional in character, and differ among economies according to their financial and fiscal policy. (By contrast, the “real” sectors of all countries usually are assumed to share a similar technology.)

Economic growth does require credit to the real sector, to be sure. But most credit today is extended against collateral, and hence is based on the ownership of assets. As Schumpeter (1934) emphasized, credit is not a “factor of production,” but a precondition for production to take place. Ever since time gaps between planting and harvesting emerged in the Neolithic era, credit has been implicit between the production, sale, and ultimate consumption of output, especially to finance long- distance trade when specialization of labor exists (Gardiner 2004; Hudson 2004a, 2004b). But it comes with a risk of overburdening the economy as bank credit creation affords an opportunity for rentier interests to install financial “tollbooths” to charge access fees in the form of interest charges and currency-transfer agio fees.

Most economic analysis leaves the financial and wealth sector invisible. For nearly two centuries, ever since David Ricardo published his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation in 1817, money has been viewed simply as a “veil” affecting commodity prices, wages, and other incomes symmetrically. Mainstream analysis focuses on production, consumption, and incomes. In addition to labor and fixed industrial capital, land rights to charge rent are often classified as a “factor of production,” along with other rent-extracting privileges. Also, it is as if the creation and allocation of interest-bearing bank credit does not affect relative prices or incomes.

It may seem ironic that Ricardo wrote just when Britain’s economy was strapped by war debts in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars that ended in 1815. The previous generation’s writers, from Adam Smith to Malachy Postlethwayt, had explained how the government paid interest on each new bond issue by adding a new excise tax to cover its interest charge (Hudson 2010). These taxes raised the cost of living and doing business, while draining the economy to pay bondholders. Yet, the banks’ Parliamentary spokesman (and indeed, lobbyist) Ricardo established a countervailing orthodoxy by claiming that money, credit, and debt did not really matter as far as production, value, and prices were concerned. His trade theory held that international prices varied only in proportion to their “real” labor costs, without taking money, credit, and debt service into account. Credit payments to bankers, and the distribution of financial assets and debts, are not seen to affect the distribution of income and wealth.

Adam Smith decried monopoly rent, especially for the special trade privileges that the British and other governments created to sell to their bondholders to reduce their war debts. Ricardo emphasized the free lunch of land rent: prices in excess of the cost of production on lands with better than marginal fertility, or implicitly on sites benefiting from favorable location. But like Smith, he treated interest as a normal cost of doing business, and hence as part of the production sector, not as an extractive rentier charge autonomous and independent from the economy of production and consumption. On this ground, he omitted banks and monopolies from his discussion of economic rent — on the assumption that their income was payment for a productive service, and hence interest seemed to be a necessary cost of production.

This assumption underlies today’s National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA). Everyone’s “income” (not including capital gains, which make no appearance in the NIPA) finds its counterpart in a “product,” in this case a service for financial income. Most revenue — and certainly most ebitda (short for “earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization”) — is generated within the FIRE sector. But is it actually part of the “real” economy’s sphere of production, consumption, and distribution (in which case it is income); or is it a charge on this sphere (in which case it is rent)? This is the distinction that Frederick Soddy (1926) drew between real wealth and “virtual wealth” on the liabilities side of society’s balance sheet.

To answer this question, it is necessary to divide the economy into a “productive” portion that creates income and surplus, and an “extractive” rentier portion siphoning off this surplus as rents: that is, as payments for property rights, credit, or kindred privileges. These are the payments on which the institutionalist school focused in the late nineteenth century. A key policy aim of the institutionalist school was to regulate prices and revenue of public utilities and monopolies in keeping with purely “economic” costs of production, which the classical economists defined as value (Hudson 2012).

Our aim is to revive the distinction between value and rent, which is all but lost in contemporary analysis. Only then can we understand how the bubble economy’s pseudo-prosperity was fueled by credit flows — debt pyramiding — to inflate asset markets in the process of transferring ownership rights to whomever was willing to take on the largest debt.

To analyze this dynamic, we must recognize that we live in “two economies.” The “real” economy is where goods and services are produced and transacted, tangible capital formation occurs, labor is hired, and productivity is boosted. Most productive income consists of wages and profits. The rentier network of financial and property claims — “Economy #2” — is where interest and economic rent are extracted. Unfortunately, this distinction is blurred in official statistics. The NIPA conflate “rental income” with “earnings,” as if all gains are “earned.” Nothing seems to be unearned or extractive. The “rent” category of revenue — the focus of two centuries of classical political economy — has disappeared into an Orwellian memory hole.

National accounts have been recast since the 1980s to present the financial and real estate sectors as “productive” (Christophers 2011). Conversely, much of the notional household income in national accounts does not exist in cash flow terms (net of interest and taxes). Barry Z. Cynamon and Steven M. Fazzari (2015) estimate that U.S. NIPA-imputed household incomes overstate actual incomes in cash flow terms by about a third.

That is what makes the seemingly empirical accounting format used in most economic analysis an expression of creditor-oriented pro-rentier ideology. Households do not receive incomes from the houses they live in. The value of the “services” their homes provide does not increase simply because house prices rise, as the national accounts fiction has it. The financial sector does not produce goods or even “real” wealth. And to the extent that it produces services, much of this serves to redirect revenues to rentiers, not to generate wages and profits.

The fiction is that all debt is required for investment in the economy’s means of production. But banks monetize debt, and attach it to the economy’s means of production and anticipated future income streams. In other words, banks do not produce goods, services, and wealth, but claims on goods, services, and wealth — i.e., Soddy’s “virtual wealth.” In the process, bank credit bids up the price of such claims and privileges because these assets are worth however much banks are willing to lend against it.

To the extent that the FIRE sector accounts for the increase in GDP, this must be paid out of other GDP components. Trade in financial and real estate assets is a zero-sum (or even negative-sum) activity, comprised largely of speculation and extracting revenue, not producing “real” output. The long-term impact must be to increase debt-to-GDP ratios, and ultimately to stifle GDP growth as the financial bubble gives way to debt deflation, austerity, unemployment, defaults, and forfeitures. This is the sense in which today’s financial sector is subject to classical rent theory, distinguishing real wealth creation from mere overhead.

“Money” consists mainly of credit creation since “loans create deposits” (McLeay, Radia and Thomas 2014). So any increase in the sum of final GDP goods-and-services transactions is mirrored in bank credit supporting these transactions (alongside inter-firm trade credit, and now money market placements as well). But since the 1980s, bank lending has risen relative to GDP (that is, relative to income). Much of the credit created since then has been used not for production, but for asset price inflation, driving up costs of living. Consumers — especially those who own real estate, stocks, and bonds — have run deeper into debt in order to maintain their living standards. Real wages have fallen a bit, while after-tax costs of living have increased.

In the United States, FICA wage withholding for Social Security and Medicare has risen to 15.2 percent, medical insurance costs have risen, education charges have risen for buyers of educational diplomas, and the mortgage bubble (which Alan Greenspan euphemized as “wealth creation”) has driven up the price of obtaining a home. It is now recognized that U.S. living standards since the 1970s have become debt-fueled, not income-supported. This went largely unnoticed until the bubble burst, since the underlying distinction in credit flows has been excluded from the economics curriculum.

Drawing the Distinction Today

It was not always like that. Economic theory today is in some ways a step backward by expunging the nineteenth-century view — and indeed that of medieval economics and even of classical antiquity — with regard to how banking and high finance intrude into economic life to impose austerity and polarize the distribution of wealth and income. More recently, Marx ([1887] 2016, 1), in Chapter 30 of Capital, distinguished “credit, whose volume grows with the growing volume of value of production” as differing from “the plethora of moneyed capital — a separate phenomenon alongside industrial production.” This implied a corollary distinction between transactions in goods and services from those in property and financial assets. Keynes (1930, 217-218) likewise distinguished between “money in the financial circulations” and “money in the industrial circulations.”

James Tobin already in 1984 worried that “we are throwing more and more of our resources, including the cream of our youth, into financial activities remote from the production of goods and services” (Tobin 1984, 14). Minsky in his later years warned against what he called “money manager capitalism” as distinct from industrial capitalism (Minsky 1987; Wray 2009). Richard Werner (2005, also 1997) adapted Irwin Fisher’s (1933) equation of exchange (MV=PT) to distinguish credit to the “real” economy from that to the financial and “wealth” sectors.

Applying these distinctions to Japanese data, Werner (2005, 222) finds “a stable relationship between ‘money’ (credit to the real sector) that enters the real economy and nominal GDP.” Likewise, Wynne Godley and Gennaro Zezza (2006, 3) observe for the United States: “Major slowdowns in past periods have often been accompanied by falls in net lending. Indeed, the two series have moved together to an extent that is somewhat surprising.” Federal Reserve economists note that many contemporary “[a]nalysts have found that over long periods of time there has been a fairly close relationship between the growth of debt of the nonfinancial sectors and aggregate economic activity” (BGFRS 2013, 76).

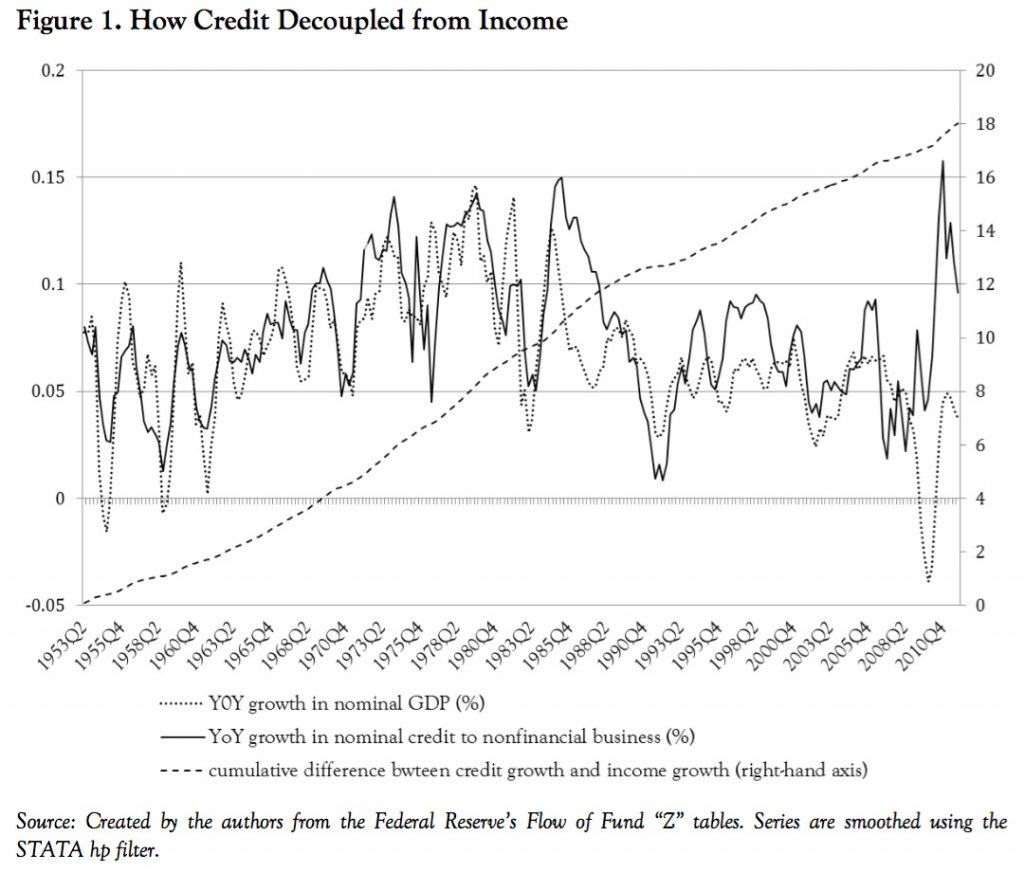

These correlations suggest a one-on-one ratio between bank credit and the non- financial sector’s economic activity (Figure 1). Growth in credit to the real sector paralleled growth in nominal U.S. GDP from the 1950s to the mid-1980s — that is, until financialization became pervasive. Allowing for technical problems of definitions and measurement, growth of bank credit to the real sector and nominal GDP growth moved almost one on one, until financial liberalization gathered steam in the early 1980s.

Figure 1 shows how, after the mid-1980s, the real sector was borrowing structurally more than its income — a remarkable trend noted by few. Wynne Godley wrote in 1999 that “during the last seven years … rapid growth could come about only as a result of a spectacular rise in private expenditure relative to income. This rise has driven the private sector into financial deficit on an unprecedented scale” (Godley 1999, 1).

Households went into negative savings territory. Firms moved from taking their returns as profits from the sale of goods and services to taking their returns as capital gains and other purely financial transactions. General Electric became GE Capital. Maria Grydaki and Dirk Bezemer (2013) explain how the rise of indebtedness explains the eerie tranquility of the bubble years, dubbed by some the “Great Moderation” which Greenspan, Bernanke, and others attributed to (their own) superior monetary policy skills. In reality, it was the “lull before the storm” of debt deflation, as a prescient author noted in 1995 (Keen 1995).

There is contemporary research supporting the classical viewpoint that debt can be a rentier burden, rather than a service to society. Wiliam Easterly, Roumeen Islam, and Joseph Stiglitz (2000) shows that the volatility of growth tends to decrease and then increase with larger financial sectors. In their article, “Shaken and Stirred: Explaining Growth Volatility” (2000, 6), the authors find that “standard macroeconomic models give short shrift to financial institutions … our analysis confirms the role that financial institutions play in economic downturns.”

In their article, “Too Much Finance?” Jean-Louis Arcand, Enrico Berkes, and Ugo Panizza (2011) argue that expectation of bailouts may lead a financial sector to expand in size beyond the social optimum. They use a variety of empirical approaches to show that “too much” finance starts to have a negative effect on output growth when credit to the private sector reaches 110 percent of GDP. Stephen G. Cecchetti, M.S. Mohanty, and Fabrizio Zampolli (2011, 1) likewise argues that, “beyond a certain level, debt is a drag on growth.” The authors estimate the threshold for government and household debt to be around 85 percent of GDP and around 90 percent for corporate debt. Likewise, as we were writing this article, the OECD and the IMF both issued reports warning of a financial overgrowth (OECD 2015; Sahay et al. 2015).

The Significance of Household Debt

The classical analysis of rent to credit and debt, combined with these recent findings, begs a key question: When does the financial system support production and income formation in a sustainable manner, and when does it support speculation and rents in the form of capital gains, rather than income formation?

The answer to this question will have to be both theoretically sound and institutionally relevant, capturing the specific forms that “unproductive” revenues take in a particular era. For the classical economists, this form was land rent. For Minsky (e.g., 1986), this form was capital gains from stock market investment “on margin” — influenced both by the 1929 Great Crash experience and by the shape of financial markets in the 1950s and 1960s, when he developed his financial instability hypothesis. But, like the classical analysis of rents, the Minskyan progression from “hedge” to “speculative” to “Ponzi” finance is not confined to land markets or stock markets.

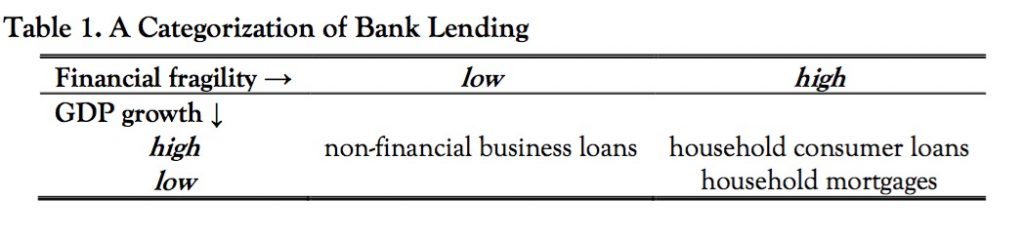

In our time, arguably the most significant form that rent extraction has taken is in the household credit markets, especially household mortgages. The contrast is with loans to non-financial business for production. A useful way to discuss this distinction is to categorize loans on two planes: their contribution to income growth and their tendency to increase financial fragility. Table 1 illustrates this. There are both conceptual and empirical grounds to draw the distinction today along these lines. We now discuss them in turn.

Conceptual Differentiation of Credit

Loans to non-financial business for production expand the economy’s investment and innovation, leading to GDP growth. A dollar drawn down as a loan and spent on domestic investment goods will increase domestic incomes proportionally. And, if the business plan on which the loan is given is good, the revenues from increased production will more than suffice to pay off the loan: financial fragility need not develop. Debt increases, but so does income. The debt/income ratio need not rise.

Like loans to non-financial business, household consumer credit provides the purchasing power and the effective demand for GDP to grow. But compared to business loans, it has two features that cause less growth for the same loan amount, and more financial fragility.

The first is a mismatch between the debt burden and the income generated from the loan. Consumer credit is not used to generate the income that will pay off the loan, as with business finance. The revenues from the loans and the debt liabilities are not on the same balance sheet. Unless macroeconomic institutions effectively transfer revenues from firms to households (e.g., as wages), consumer credit creates financial vulnerabilities in household balance sheets.

Second, in terms of how much income is generated for a given debt service burden, household consumer credit is not an efficient way to finance production due to its usually very high interest rates. A number of studies have shown that, compared to business credit, the growth impact of household credit is small (Beck et al. 2012; Jappelli and Pagano 1994; Xu 2000). For every dollar realized in value added by extending credit to households which spend it with firms, more dollars of debt servicing must be paid than is the case for business credit. Bezemer (2012) shows that the ratio of the growth in private debt and the growth in GDP moved from 2:1 on average in the 1950s and 1960s to 4:1 in the 1990s and 2000s. These are rough, but still telling indications. The trend is not exclusively attributable to growth in consumer credit since the 1960s, for an even larger category of household credit is household mortgage credit.

Like consumer credit, household mortgage credit increases the debt, but not the income of households. This increases financial fragility. Unlike consumer credit, mortgage credit for existing properties does not generate current income anywhere else — at least, not in the classical taxonomy of incomes and rents. Mortgage credit is extended to buy assets, mostly already existing. It generates capital gains on real estate, not income from producing goods and services. The distinction becomes blurred to the extent that mortgages are used to finance personal consumption (especially “equity loans” to homeowners) or new construction, but that is a minor part of the total volume of mortgage loans.

Mortgages are also special in that real estate assets have grown into the largest asset market in all western economies, and the one with the most widespread participation. Following classical analysis, if every real estate asset bought on credit skims off the income of the owner-borrower, then the rise in home ownership since the 1970s has sharply increased rent extraction and turned it into a flow of interest to mortgage lenders. Securitization added another dimension to this. Not only domestic homeowners, but also global investors can participate in the mortgage market. As in a Ponzi scheme, the larger the flows of income the mortgage market commands, the longer the scheme can continue. This is a key reason for the unusually long mortgage credit boom synchronized across western economies from the 1990s to 2007.

Household mortgage loans are also unique among types of bank loans for their macroeconomic effects in downturns — that is, for their potential to increase the financial fragility of entire economies. Because of widely held debt-leveraged asset ownership, the effects of falling house prices and negative equity on household consumption are significant on a macroeconomic level. And because real estate collateral is a key asset on bank balance sheets, there is also an effect on banks’ own financial fragility. This leads to lending restrictions not only in mortgages, but also to nonfinancial business.

Empirical Evidence

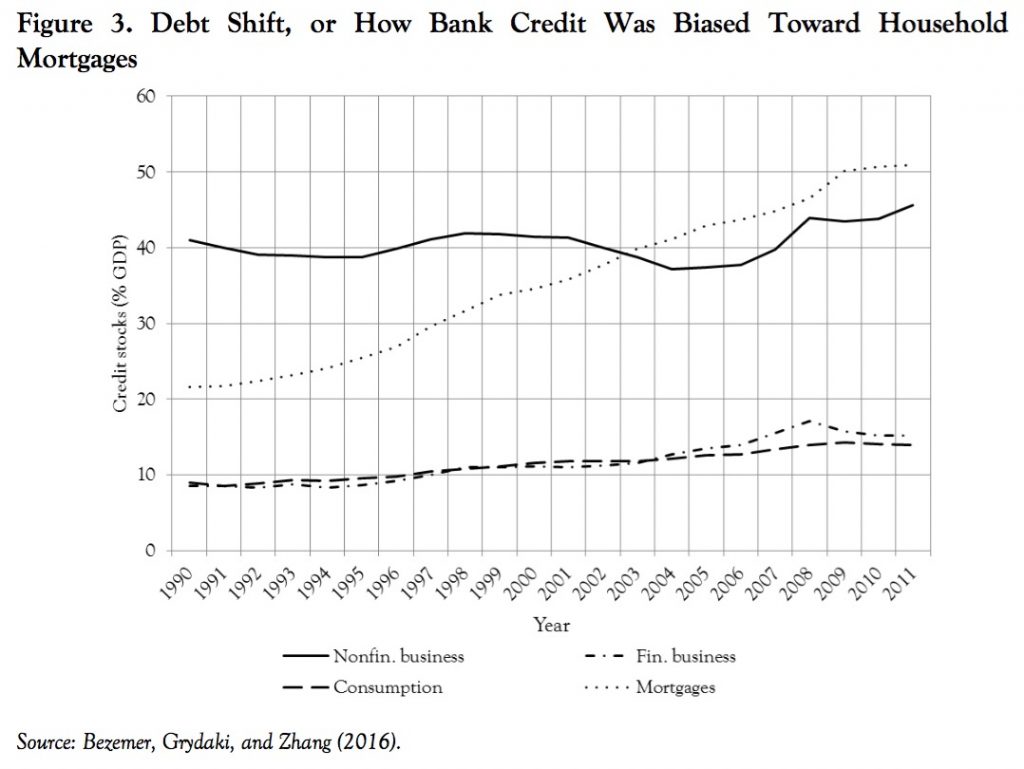

A number of empirical studies have been undertaken in the last few years to corroborate the above conceptual discussion. In Figure 2, based on calculations by Dirk Bezemer, Maria Grydaki, and Lu Zhang (2016), we plot the correlation of income growth with credit stocks scaled by GDP. This provides a proxy for the growth effect of credit over time. The trend is downward from the mid-1980s, and from the 1990s the correlation coefficient is not significantly different from zero. Credit was no longer “good for growth,” as many had for so long believed (from King and Levine 1993 to Ang 2008).

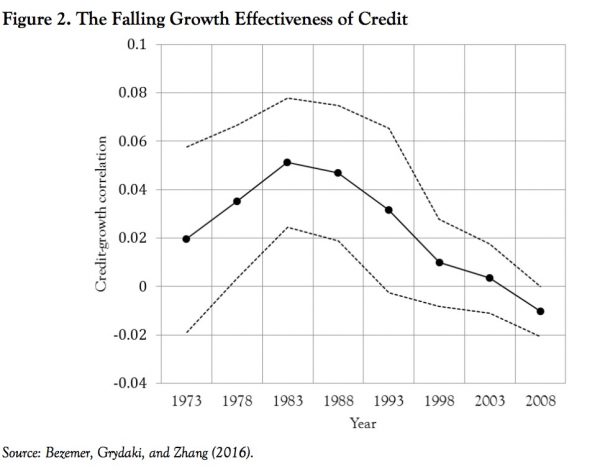

A major reason for this trend was that credit was extended increasingly to households, not business. Figure 3 shows the change in bank credit allocation from 1990 to 2011 for a balanced panel of 14 OECD economies. While the total credit stock expanded enormously in the 1990s and 2000, credit to nonfinancial business was stagnant at about 40 percent of GDP, while its share in overall credit plummeted. By contrast, the share of household mortgage credit issued by banks rose from about 20 to 50 percent of all credit. Òscar Jordà, Alan Taylor, and Moritz Schularick (2014), in their excellent historical study “The Great Mortgaging,” report for a sample of 17 countries an increase from 30 to 60 percent in household mortgage credit as share of GDP since 1900, with by far most of that increase since the 1970s. The costs to income growth were large. Torsten Beck et al. (2012), Bezemer, Grydaki, and Zhang (2016), and Jordà, Taylor, and Schularick (2014) all show with advanced statistical analysis that the contribution of household credit to income growth has become negligible or is plainly negative. Last year, IMF and OECD reports made the same point (Sahay et al. 2015; Cornede, Denk and Hoeller 2015).

Such large stocks of household credit do not just depress income growth. As we noted above, they also increase financial fragility. A large number of recent cross- country studies report that the expansion of household credit is positively related to crisis probability (Barba and Pivetti 2009; Büyükkarabacak and Valev 2010; Frankel and Saravelos 2012; Obstfeld and Rogoff 2009; Rose and Spiegel 2011; Sutherland et al. 2012). There is also a clear impact on the length and severity of post-2008 recessions. The mechanism is shown by Karen Dynan (2012) and by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi (2014) for the United States.

More leveraged U.S. homeowners have cut back their spending after 2007. But the nefarious effect of more private credit — a rise which, as we have seen, is driven by the growth in household mortgage credit — on the severity of the post-crisis recession is not confined to the US. Philip Lane and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti (2011) find that, on average across a large swath of countries, falls in output, consumption, and domestic demand in 2008–2009 correlate to the pre-crisis increases in the ratio of private credit to GDP.

S. Pelin Berkmen et al. (2012) show that the gap between realized output growth in 2009 with the more optimistic pre-crisis forecasts is strongly correlated to pre-crisis credit growth. They infer that pre- crisis household credit growth is a prime suspect for the causes of the depth of the recession. Similar findings are reported by Cecchetti, Mohanty, and Zampolli (2011), Stijn Claessens et al. (2010); Tatiana Didier, Constantino Hevia, and Sergio Schmukler (2012), and others.

In sum, if we divide bank credit into three categories as in Table 1, our categorization suggests that both household consumer credit and loans to non- financial business are productive — in the sense of providing the purchasing power to support production of goods and services — but with greater buildup of financial fragility in the case of consumer credit. Installment loans were instrumental in developing mass markets for cars, but this made household balance sheets more vulnerable. Many U.S. students could not attain a college degree without student loans. In this sense, these loans are productive by enabling graduates to earn more. But if students cannot find jobs that pay enough extra income to service the loan, it is not productive. In any event, the debt burden after graduation weakens their household balance sheets. In this sense, mortgages and other debts tend to increase financial fragility.

This categorization is not exhaustive and should be further refined within each category. For instance, much lending to non-financial business does not support production. It may take the form of mortgage lending pushing up commercial real estate prices, or loans for mergers and takeovers, or for stock buyback programs. Conversely, household mortgages may be productive to the extent that they are used for new construction. They thus should be distinguished from margin (brokers’) loans and interest-only loans to “flip” houses or commercial real estate, which are unproductive.

These more fine-grained categories cannot be observed in the data in a cross- country consistent manner as done in the above studies. They can be applied in country studies building on the Figure 3 distinctions. But a major obstacle to this research program is not empirical, but paradigmatic: the impression that debt-

leveraged real estate valuations represent the economy’s wealth, with little recognition that its financing structures undermine wealth creation. To this we now turn.

The Rentier Economy: Wealth or Overhead?

Bank credit to the nonbank “asset” sector (mainly for real estate, but also LBOs and takeover loans to buy companies, margin loans for stock and bond arbitrage, and derivative bets) does not enter the “real sector” to finance tangible capital formation or wages. Its principal immediate effect is to inflate prices for property and other assets. Recent econometric analysis confirms that mortgage credit causes house price to increase (Favara and Imbs 2014) — and not just vice versa, as in the demand-driven textbook credit market theories.

How does this asset-price inflation affect the economy of production and wages and profits? In due course this process involves increasing the debt-to-GDP ratio by raising household debt, mortgage debt, corporate and state, local and government debt levels. This debt requires the real sector to pay debt service — a fact that prompted Benjamin Friedman (2009, 34) to write that “an important question — which no one seems interested in addressing — is what fraction of the economy’s total returns … is absorbed up front by the financial industry.”

To ignore this rising fraction is to ignore debt and its consequence: debt deflation of the “real” economy. Of course, the reason why debt leveraging continued so long was precisely because credit to the FIRE sector inflated asset prices faster than debt service rose — as long as interest rates were falling. The tidal wave of post-1980 central bank and commercial bank liquidity drove interest rates down, increasing capitalization ratios for rental income corporate cash flow.

The result was the greatest bond market rally in history, as the soaring money supply drove down interest rates from their 20-percent high in 1980 to under 1.0 percent after 2008.

A debt-leveraged rise in asset prices has a liability counterpart on the balance sheet of households and firms. Homes, commercial properties, stocks, and bonds are loaded down with debt as they are traded many times by investors or speculators taking out larger and larger loans at easier and easier terms: lower down-payments, zero-amortization (interest-only) loans and outright “liars’ loans” with brokers and their bankers filing false income declarations and crooked property valuations, to be packaged and sold to pension funds, German Landesbanks, and other institutional investors. Each new debt-leveraged sale may bid up prices for these assets.

But the credit can be repaid (with interest) only by withdrawing payment from the “real” sector (out of profits and wages), or by selling financialized assets, or borrowing yet more credit (“Ponzi lending”). The rising indebtedness approaching the 2008 crest was carried not so much by diverting current income away from buying goods and services or by selling financial assets, but by loading down the economy’s balance sheet and national income with yet more debt (that is, by borrowing the interest falling due, for example, by home equity loans). What kept the “Great Moderation” income growth and inflation levels so “moderate” was an exponential flood of credit (i.e., debt) to carry the accumulation and compounding of interest. It was like having to finance a chain letter on an economy-wide scale, with banks creating the credit to keep the scheme going.

This is the institutional reality behind the negative correlation coefficient of credit and income growth, reported in the previous section. In fact, to assess credit for its income growth potential is to miss its true function in the rentier economic system. The FIRE sector’s real estate, financial system, monopolies, and other rent-extracting “tollbooth” privileges are not valued in terms of their contribution to production or living standards, but by how much they can extract from the economy. By classical definition, these rentier payments are not technologically necessary for production, distribution, and consumption. They are not investments in the economy’s productive capacity, but extraction from the surplus it produces.

Just as classical rents were defined as transfer payments rather than earned by factors of production, financial investment by itself is a zero-sum activity. With interest and related charges taken into account, it is a negative-sum activity. The problem with the transfer character of financial payments is that the assets backing the loans to buy them, must plunge in price at the point where debt service diverts so much income and liquidity from the real sector that debt-financed asset-price inflation becomes unsustainable. This is confirmed by a recent Bank of International Settlements study. Mathias Drehman and Mikael Juselius (2015) report that debt- service ratios are an accurate early warning signal of impending systemic banking crises, and strongly related to the size of the subsequent output losses.

Financial markets can grow sustainably — that is, without rising fragility — only when loans to the real sector are self-amortizing. For instance, the thirty-year home mortgages typical after World War II were paid over the working life of homebuyers. The interest charges often added up to more than the property’s seller received, but the loans financed about two million new homes built each year in the United States in the early post-war decades, creating enough economic growth to pay down the loans.

When building activity slowed, debt growth was kept going by financial engineering and lending at declining rates of interest and on easier payment terms. This is what happened from the 1980s to 2008, and especially after 2001, as the real estate bubble replaced the dot.com bubble of the 1990s. Prices for rent-yielding and financial assets were bid up relative to the size of the real economy. Housing and other property prices (as well as prices for stocks and bonds) rose relative to wages, widening the polarization between property owners and labor. Christopher Brown (2007) showed already before the crisis how household credit is central to this divergence. Financial engineering, which freed household incomes and home equity to be invested in speculative assets, greatly increased the amount of borrowing that household could and did take on. By applying Minsky’s categorization, he identified the move from speculative to Ponzi financing structures, and concluded that debt growth, and the consumption growth based on it, was not sustainable. Because a Ponzi scheme is a “pyramid scheme,” sucking money from a broad base to a narrow top, financial engineering also increased inequality (see also Brown 2008).

This polarization occurred largely because resources were flowing to FIRE speculation and arbitrage instead of to more moderate-return, fixed capital formation. The main dynamic was financial, not the industrial relationship between employers and workers described by socialists a century ago. It originated in the United States and spread to most industrial economies via the carry trade and other international lending in an increasingly deregulated environment. Toxic financial waste became the most profitable product and the fastest way to quick fortunes, selling junk mortgages to institutional investors in a financial free-for-all.

Robin Greenwood and David Scharfstein’s (2012) “The Growth of Modern Finance” provides a telling empirical illustration of the transfer (rather than income- generating) character of today’s financial sector. In addition to showing that the financial industry accounted for 7.9 percent of U.S. GDP in 2007 (up from 2.8 percent in 1950), they calculated that much of this took the form of fees and markups — the quintessential transfer payments. Such charges by asset managers of mutual funds, hedge funds, and private equity concerns now account for 36 percent of the growth in the financial sector’s share of the economy, as Gretchen Morgenson (2012) reports. Finance also accounts for some 40 percent of corporate profits. But our point is that financial “profits” in the classical scheme are largely rents, not profit. They are not the same thing as industrial earnings from tangible capital formation.

Capital Gains Are Linked to Debt Growth

This raises a vital question for today’s economies. Can debt-financed rising asset prices make economies richer on a sustainable basis? If the aim of raising asset prices is to increase the capitalization rate of rents and profits by lowering interest rates, can pension funds, insurance companies, and retirees save enough for their retirement out of current earnings, or can they live by capital gains alone?

Asset prices can rise only by debt creation or by diverting current income. The recognition that such debt-fueled inflation of asset prices is a form of rent extraction is central to our analysis of its unsustainability. By contrast, the now conventional economic models give us no handle to even start addressing these phenomena. By viewing capital gains as transfers instead of as income, we define the long-term sustainability of capital gains and asset prices in terms of trends in disposable income plus debt growth. Just as a Ponzi scheme must collapse with mathematical certainty (even though the timing of the collapse is uncertain), so it is with asset markets that expand faster than income growth. The divergence between income growth and rent extraction (asset price growth and financial transfers) is unsustainable, although, by going global, asset markets can be kept inflated over decades.

What obscures this dynamic is a micro-macro fallacy. Homeowners thought they were getting rich as real estate prices were inflated by easier bank credit. According to representative-agent models, the nation was getting rich as new buyers of homes, stocks, and bonds took on larger debts to sustain this price rise. Alan Greenspan applauded this as wealth creation. Individuals borrowed against their capital gains, hoping that future gains would pay off the new debt they were taking on.

This is not how classical economists described the profitability and accumulation of capital under industrial capitalism. Gains were supposed to be achieved by “real” growth, not by asset-price inflation. The financial drive for capital gains has become decoupled from tangible capital investment and employment.

On the individual micro-level, it may be of little concern whether gains are made by higher asset prices or from direct investment to produce and sell goods. To the corporate manager or raider, speculator or entrepreneur, the financial returns appear equal. But on the society-wide macro-level, there is a micro-macro paradox or “fallacy of composition.” Capital gains via asset-price inflation must be fueled by rising indebtedness of the overall economy. Prices for assets will rise by however much a bank is willing to lend, and asset price gains over and above income constitute debt growth in the economy.

In the end, “wealth creation” in the real estate market was fueled by mortgage loans larger than the entire GDP. Each loan was a debt: total mortgage debt doubled relative to the economy in 25 years. That was the cost of “wealth creation.” It is not real wealth. It is debt which is a claim on wealth. It derives not from income earned by adding to the economy’s “real” surplus, but is a form of rent extraction eating into the economy’s surplus.

John Stuart Mill described this contrast in his Principles of Political Economy (1848, 1): “All funds from which the possessor derives an income … are to him equivalent to capital. But to transfer hastily and inconsiderately to the general point of view, propositions which are true of the individual, has been a source of innumerable errors in political economy.” In the United States, John Bates Clark popularized the superficial “businessman’s” perspective, viewing “cost value” as whatever a buyer of a real estate property or other asset pays. No regard was paid to economically and socially necessary cost-value, which in the classical analysis is ultimately resolvable into the cost of labor. Cost-value is different from a gift of nature, and also differs from financial and other rentier charges built into the acquisition price. These are rents, not costs. But as Simon Patten stated a century ago, this difference faded from economists’ memory (see Hudson 2011, 873). Clark’s post- classical approach became the preferred Weltanschauung of financial and real estate interests (Clark in Hudson 2011, 875).

“In the present instance,” Mill (1848, 2) had elaborated, “that which is virtually capital to the individual, is or is not capital to the nation, according as the fund … has or has not been dissipated by somebody else.” In other words, funds not used (Mill used the word “dissipated”) in the real economy provide revenue to their owner, but not to the economy for which this revenue is an overhead cost. Mill’s term “virtually capital to the individual” is kindred to Frederick Soddy’s (1926) term “virtual wealth,” referring to financial securities and debt claims on wealth — its mirror image on the liabilities side of the balance sheet. In a bubble economy, the magnitude of such “virtual wealth” is inflated in excess of “real wealth,” supporting the ability to carry higher debts on an economy-wide level.

Financial and other investors focus on total returns, defined as income plus “capital” gains. But although the original U.S. income tax code treated capital gains as income, these asset-price gains do not appear in the NIPA. The logic of their exclusion seems to be that what is not seen has less of a chance of being taxed. That is why financial assets are called “invisibles,” in contrast to land as the most visible “hard” asset.

Growth of Financial Rents and Its Consequences

We have developed the argument that finance is not the economy. Rent is not income, and asset values do not represent wealth, but rather a claim on the economy’s wealth. They are an overhead cost which is not necessary from a production point of view. We have shown that what keeps asset values rising and the overhead burden growing is debt — in particular, household mortgage debt. We reviewed many recent econometric studies which report that debt hurts income growth. It remains for us to discuss the forms in which this occurs.

An economy based increasingly on rent extraction by the few and debt buildup by the many is, in essence, the feudal model applied in a sophisticated financial system. It is an economy where resources flow to the FIRE sector rather than to moderate-return fixed capital formation. Such economies polarize increasingly between property owners and industry/labor, creating financial tensions as imbalances build up. It ends in tears as debts overwhelm productive structures and household budgets. Asset prices fall, and land and houses are forfeited.

This is the age-old pattern of classical debt crises. It occurred in Babylonia, Israel, and Rome. Yet, despite its relevance to the United States and Europe today, this experience is virtually unknown in today’s academic and policy circles. There is no perspective forum in which to ask in what forms debt growth may hurt the economy today. To start to fill the gap, we now consider what “too much finance” (Arcand, Berkes and Panizza 2011) does to the economy. It decreases productivity and investment, and increases inequality and volatility. In each of these mechanisms, the role of household mortgages is pivotal.

Loss of Productivity

Faced with the choice between the arduous long-term planning and marketing expense of real-sector investment with single digit returns, the quick (and lower-taxed) capital gains on financial and real estate products offering double-digit returns have lured investors. The main connection to tangible capital formation is negative by diverting new borrowing away from the real sector, as recent studies show (Chakraborty Goldstein and McKinlay 2014).

Industrial companies were turned over to “financial engineers” whose business model was to take their returns in the form of capital gains from stock buyback programs, higher dividend pay-outs, and debt- financed asset takeovers (Hudson 2012, 2015a, 2015b). Charting the ensuing rise of interest and capital gains relative to dividends, and of portfolio income relative to normal cash flow in America’s nonfinancial businesses, Greta Krippner (2005, 182) concludes: “One indication of financialization is the extent to which non-financial firms derive revenues from financial investments as opposed to productive activities.”

Much as real estate speculators grow rich on inflated land values rather than production, so financialization threatens to undermine long-term growth. Since the 1980s, the major OECD economies have seen rising capital gains divert bank credit and other financial investment away from industrial productivity growth. Engelbert Stockhammer (2004) shows a clear link between financialization and lower fixed capital formation rates.

This turns out to be finance capitalism’s analogue to the falling rate of profit in industrial capitalism. Instead of depreciation of capital equipment and other fixed investment (a return of capital investment) rising as a proportion of corporate cash flow as production becomes more capital-intensive (“roundabout,” as the Austrians say), it is interest charges that rise. Adam Smith assumed that the rate of profit would be twice the rate of interest, so that returns could be shared equally between the “silent backer” and entrepreneur. But as bonds and bank loans replace equity, interest expands as a proportion of cash flow. Nothing like this was anticipated during the high tide of industrial capitalism.

Inequality

Minsky (1986) described financial systems as tending to develop into Ponzi schemes if unchecked. Echoing Marx ([1887] 2016), he focused on the exponential overgrowth and instability inherent in the “miracle of compound interest,” underlying such schemes and indeed financialized economies. For the economy at large, such growth sucks revenue and wealth from the broad base to the narrow top, impoverishing the many to enrich the few.

Indeed, income inequality has risen since the late 1980s in most OECD countries. Top incomes have skyrocketed (Atkinson, Piketty and Saez 2011). Thomas Piketty (2014) casts this in terms of a redistribution of income from wage earners to owners of capital, but “capital” includes both physical production assets and real estate and financial assets. Given the large role of real estate lending, it is unsurprising that “the growth of the U.S. financial sector has contributed to the exacerbation of inequality in recent decades” (van Arnum and Naples 2013, 1158). Christopher Brown (2008, 9, Figure 1.3) shows how consumer borrowing has supported effective demand since 1995, and how credit market debt owed by the household sector increased exponentially from the turn of the millennium.

Contrary to textbook consensus, household debt had macroeconomic significance, as Brown (2008) shows. More recently, an OECD report also found that financial sector growth in support of household credit expansion exacerbates income inequality (Cournède, Denk and Hoeller 2015).

U.S. data shows that through the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, the top 10-percent share remained stable at 30 percent, but started to rise with the explosion of financial credit in the 1980s. However, by 2009, the top 10 percent of income “earners” received about half of the national income, not taking into account capital gains, which is where the largest returns have been made. Anthony Atkinson, Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez (2011) show that this is a general trend in most developed economies.

Rising leverage increases the rate of return for investors who borrow when asset prices are rising more rapidly than their debt service. But the economy becomes more indebted while creating highly debt-leveraged financial wealth at the top. The resulting financial fragility may appear deceptively stable and self-sustaining as long as asset prices rise at least as fast as debt. When home prices are soaring, owners may not resent (or even notice) the widening inequality of wealth as the top “One Percent” widen their lead over the bottom “99 Percent.” Home equity loans may give the impression that homes are “piggy banks,” conflating the rising debt attached to them with savings in a bank account. Real savings do not have to be paid off later. Mortgage borrowing does.

The “Bubble Illusion” may keep spending power on a rising trend even while real wage income stagnates, as it has done in the United States since the late 1970s. Our analysis that Ponzi-like financial structures exacerbate inequality is reflected in the joint rise of inequality and the share of bank credit to the FIRE sector, as Bezemer (2012a, 2012b) demonstrates. Brown (2007) showed already before the crisis how household credit is central to this. Financial engineering, which freed household incomes and home equity to be invested in speculative assets, greatly increased the amount of borrowing that household could and did take on.

Instability

The Ponzi dynamic explains why financialization first leads to more stability, but then to instability and crises. Easterly, Islam, and Stiglitz (2000) showed that the volatility of economic growth decreases as the financial sector develops in its early stages, but that finance means more instability when credit-to-GDP ratios rise above 100 percent in more “financially mature” (i.e., debt-ridden) economies. Is it a coincidence that this was just the level above which Arcand, Berkes, and Panizza (2011) find that credit growth starts slowing down real-sector growth? After the crisis, a plethora of research has shown that a larger credit overhead increases the probability of a financial crisis and deepens post-crisis recessions (see, for instance, Barba and Pivetti 2009; Berkmen et al. 2012; Claessens et al. 2010)

Concluding Remarks

The banking and financial system may fund productive investment, create real wealth, and increase living standards; or it may simply add to overhead, extracting income to pay financial, property, and other rentier claimants. That is the dual potential of the web of financial credit, property rights, and debts (and their returns in the form of interest, economic rent, and capital gains) vis-à-vis the “real” economy of production and consumption.

The key question is whether finance will be industrialized — the hope of nineteenth-century bank reformers — or whether industry will be financialized, as is occurring today. Corporate stock buybacks or even a leveraged buyout may be the first step toward stripping capital and the road to bankruptcy rather than funding tangible capital formation.

In Keynesian terms, savings may equal new capital investment to produce more goods and services; or they may be used to buy real estate, companies, and other property already in place or financial securities already issued, bidding up their price and making wealth more expensive relative to what wage-earners and new businessmen can make. Classical political economy framed this problem by distinguishing earned from unearned income and productive from unproductive labor, investment, and credit. By the early twentieth century, Thorstein Veblen and others were distinguishing the dynamics of the emerging finance capitalism from those of industrial capitalism.

The old nemesis — a land aristocracy receiving rent simply by virtue of having inherited their land, ultimately from its Norman conquerors — was selling its property to buyers on credit. In effect, landlords replaced rental claims with financial claims, evolving into a financial elite of bankers and bondholders.

Conventional theory today assumes that income equals expenditure, as if banks merely lend out the savings of depositors to borrowers who are more “impatient” to spend the money. In this view, credit creation is not an independent and additional source of finance for investment or consumption (contrary to Marx, Veblen, Schumpeter, Minsky, and other sophisticated analysts of finance capitalism). “Capital” gains do not even appear in the NIPA, nor is any meaningful measure provided by the Federal Reserve’s flow-of-funds statistics. Economists thus are operating “blindly.” This is no accident, given the interest of FIRE sector lobbyists in making such gains and unearned income invisible, and hence not discussed as a major political issue.

We therefore need to start afresh. The credit system has been warped into an increasingly perverse interface with rent-extracting activities. Bank credit is directed into the property sector, with preference to rent-extraction privileges, not the goods- and-service sector. In boom times, the financial sector injects more credit into the real estate, stock, and bond markets (and, to a lesser extent, to consumers via “home equity” loans and credit card debt) than it extracts in debt service (interest and amortization). The effect is to increase asset prices faster than debt levels. Applauded as “wealth creation,” this asset-price inflation improves the economy’s net worth in the short run.

But as the crash approaches, banks deem fewer borrowers creditworthy and may simply resort to fraud (“liars’ loans,” in which the liars are real estate brokers, property appraisers and their bankers, and Wall Street junk-mortgage packagers). Exponential loan growth can be prolonged only by a financial “race to the bottom” via reckless and increasingly fraudulent lending. Some banks seek to increase their market share by hook or by crook, prompting their rivals to try to hold onto their share by “loosening” their own lending standards. This is what happened when Countrywide, Wachovia, WaMu, and other banks innovated in the junk-mortgage market after 2001, followed by a host of community banks. Rising fragility was catalyzed by Wall Street and Federal Reserve enablers and bond-rating agencies, while a compliant U.S. Justice Department effectively decriminalized financial fraud.

The 2008 financial crash pushed the bubble economy to a new stage, characterized by foreclosures and bailouts. Faced with a choice between saving the “real” economy by writing down its debt burden or reimbursing the banks (and ultimately their bondholders and counterparties) for losses and defaults on loans gone bad, the policy response of the US and European governments and their central banks was to save the banks and bondholders (who incidentally are the largest class of political campaign contributors). This policy choice preserved the remarkable gains that the “One Percent” had made, while keeping the debts in place for the “99 Percent.” This accelerated the polarization that already was gaining momentum between creditors and debtors. The political consequence was to subsidize the emerging financial oligarchy.

In light of the fact that “debts that can’t be paid, won’t be paid,” the policy question concerns how they “won’t be paid.” Will resolving the debt overhang favor creditors or debtors? Will it take the form of wage garnishments and foreclosure, and privatization selloffs by distressed governments? Or will it take the form of debt write- downs to bring mortgage debts and student loan debts in line with the ability to pay? This policy choice will determine whether “real” economic growth will recover or succumb to post-bubble depression, negative equity, emigration of young skilled labor, and a “lost decade.” According to our analysis, the present choice of financial and fiscal austerity in much of Europe threatens to subject debt-ridden economies to needless tragedy.

See original post for references

It seems inevitable to me that the question of “What must be done?” will come down to this;

The following quote is from one of my comments on yesterdays education post.

I think we are all, from top to bottom, starting to realize that our present situation is the result of participation in a fairy-tale economy conjured out of thin air by a clueless elite who because of being blinded by self-interest failed to see that their behavior could not in any way be sustained, and would inevitably lead to economic collapse.

The question now is, how long will it take us to accept the necessity to abandon the neoliberal consensus and take the common sense remedies being offered?

It’s sort of depressing that it’s taken some eight years to reach this point, where we’re no longer arguing “what happened?”, but more and more understanding “Here’s what we must do.”.

I’m starting to think that more than anything this highlights the fact that We the People made a dreadful mistake in thinking that we could reap the benefits of our democracy with so little personal effort/involvement.

So if we want to see these remedies enacted, we’re going to have to double-down on the sort of effort that resulted in Bernie Sanders candidacy and reinforce the growing consensus the Enough is Enough.

It will favor the wealthy.

That is why I am leaving the USA permanently.

“traditional assumption that the banking system’s major role is to provide credit to finance tangible capital investment in new means of production. Banks mainly finance the purchase and transfer of property and financial assets already in place.”

This certainly fits my experience at several small companies. Banks will lend a small company money only if they don’t need it.

Steve

August 19, 2016 at 12:14 pm

What is the old joke about bankers? A banker lends you his umbrella when it is sunny and wants it back when it rains.

Really, is it so complicated? 50 years of making a few people who don’t need to borrow wealthier and wealthier, and soaking up most of the money, while those who spend almost all of their income have less, and less, and less….and less income to spend OR to borrow. And yet this simple fact seems beyond the comprehension of the FED…OR – is it fully comprehended??? and the FED members are selected on the basis of never, ever speaking the simple truth.

I have been saying since the early 90’s that wealth inequality will strangle the formation of pools of capital and NOBODY has yet listened. I wrote a paper in 1994 for a macroeconomics class in college that predicted a substantial decline in residential real estate prices to come based on the fact that median household income could no longer support payments on the median house price, I got a B on the paper, the prof took off a grade for the absurdity that house prices could ever go down, even though the paper was very well written and as we know I ended up being right.

What I am getting at is persons might get distressed to an extreme, but societies will always find denial and suffering the more attractive option until their own survival is in jeopardy. The propaganda of the rich is very effective in this, if you keep your nose clean and work hard you will be middle class in America, if you are not middle class then you have to work harder and keep your nose cleaner. If you are not rich like us you are to blame. How do you rebel against failure and dire economic circumstances when you are told over and over that your failure is your own laziness and poor habits?

But, eventually propaganda fails and you get your French Revolution moments. Trust me when I say that the top 1% and some of the rest of the top 10% got the message with Trump and Sanders that the French Revolution stage is closer than they thought. They are preparing for it. The Bush family did not buy 300,000 acres of land in Paraguay because the appreciated the views.

Great post. Much to consider. A few thoughts about a correlation (and correlation is not causation, I know.)

“Why have economies polarized so sharply since the 1980s, and especially since the 2008 crisis? How did we get so indebted without real wage and living standards rising, while cities, states, and entire nations are falling into default?”

Starting about 1982-3 US manufacturers began laying off thousands of workers who would not be called back, first in response to an economic downturn, then to boost stock prices. Permanently laying off workers and looting company pension plans to boost stock prices gathered pace until, in the late 80’s, companies started moving manufacturing off-shore. First to Mexico. Later to China and elsewhere, closing on-shore manufacturing plants. My opinion is that on-shore manufacturing sector provided both good jobs *and* stable income for service industries like the FIRE sector. On-shore manufacturing also paid taxes to state and local govts that supported k-12 and higher ed schools and transportation/infrastructure projects.

My opinion ( based on correlations, not on data analysis): As the real economy based on productive/manufacturing work was off-shored, the FIRE sector of the economy began charging more to people with fewer resources. Their business models changed from supporting production in a large arena to rent extraction in a much smaller arena. Did their business models change in response to off-shoring business loss, or did it change prior to off-shoring and help drive off-shoring? No idea.

Is the FIRE sector now extracting so much rent they are preventing the formation of new, real economy productive enterprises?

Thanks for this post.

Yes, ask anybody who went to a bank in the last twenty years looking to finance an expansion of manufacturing.

If their business plan did not include off-shoring the plant, they were most often summarily refused.

And probably lectured.

The detailed information is appreciated, but I find the absence of discussion regarding the political factors a bit telling. The evolution of finance has only been made possible through the shifts in the political and hence regulatory environments. Bezemer and Hudson would need far more words to document the correlation between these political changes and the practice of finance that exists today. To paraphrase Sanders, their model is fraud. The greatest return on investment in the history of finance has been the purchase of politicians. Not only in money, but in the freedom from laws and accountability for the men that helm these institutions.

The choice to be made is not merely the choice between policies which the authors close with. The choice is whether the political power structures will continue to be staffed by those subservient to greed of a small number of men, or will they return to some semblance of actually serving the greater good.

Excellent comment. We are where we are because it has been government policy to make the rich richer and the poor poorer . It hasn’t happened by accident. Remember trickle-down economics. It was all hogwash, but we the people took it on board and now anyone who cares to look , however cursorily, realises it was all a con . Unravelling it is not going to be easy and unless and until significant about -turn policy changes are made nothing will change for the better . Methinks there will tears before bedtime .

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!!!!!

KYrocky

August 19, 2016 at 12:36 pm

I think you hit the nail right on the head. And the key word is CHOICE – it is not a law of physics that wages have to be stagnant or go down, and that jobs have to move overseas. These are choices – the choice being more inequality or not. And it is apparent that those with a billion are not satisfied with 10 billion, or even a 100 billion.

The main conceptual leap is to understand that the middle class, or economic justice for that matter, is a created phenomenon, not some law of nature or the market. It is a choice, made by individual or societal power to bring about the desired social outcomes.

When that fact is widely accepted, either we experience massive change very quickly, or the guns will come out. The propaganda is wearing very thin these days so keeping the game going as presently played is becoming highly problematic. War as a tool of sidetracking that realization is also loosing its potency.

The current elite seem incapable of not overplaying their hand. This does not bode well for a peaceful future.

“the theoretical framework that should guide analysis of the post-bubble economy”, should we ever actually get to one. I get the point that some aspects of Greenspan’s residual bubble burst in 2008, but it has somehow been paper mached into a seemingly permanent bubble shape even though there is nothing left inside. Can you make paper mache with fiat?

This is really a great post that repays multiple readings.

To begin with Randian philosopy summations:

“Ayn Rand’s “philosophy” is nearly perfect in its immorality, which makes the size of her audience all the more ominous and symptomatic as we enter a curious new phase in our society….To justify and extol human greed and egotism is to my mind not only immoral, but evil.”

—Gore Vidal, Esquire Magazine, 1961

”Conspicuous by their absence from Rand’s list of virtues are the “virtues of benevolence,” such as kindness, charity, generosity, and forgiveness.”

—Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy[1]

Greenspan was a Rand disciple. Upon re-reading this post I think much of what’s happened is the determination by Greenspan and fellow alcolytes to “prove” Randian Objectivism correct – even if it requires govt propping up. Oh, the irony. Think the Chicago School and the Greenspan ‘put’.

From the article:

“Since the 1980s, the economy has been in a long cycle in which increasing bank credit has inflated prices for real estate, stocks, and bonds, leading borrowers to hope that capital gains will continue.”

This is Randian propping up by govt action. Without the govt prop it would fail. We are not all John Galts. Nor can John Galt succeed in a failing economy. Or, apparently, without major govt propping up.

“Finance is Not the Economy,; Rent is Not Income”

Ah, but it can be conflated as such, wherein higher prices make Objectivism look real. When, in essence, it is only (per Lambert comment) Ptolemaic astronomy.

Thanks again for this post.

adding:

charitably: maybe Rand conflated ‘the self’ with ‘greed’.

Steve Keen discussed some of the problems with mainstream economists and failure to take into account private debt today on BBC’s HardTalk today. Of course he got a lot of pushback, but overall it was an interesting discussion/interview.

The podcast download is available here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p004t1s0/episodes/downloads

I wrote this earlier today before seeing this post as a way to flush out my thoughts, didn’t change a word since seeing this. It is essentially the colloquial cliff notes to your piece.:

This American Life, the podcast, has a great episode about the GFC called “The Giant Pool of Money.” Since Reagan cut the top tax rate from 70% to 30% that pool of money has been building and building always looking for a profitable investment.

Did you notice how the Wage share of GDP has flat lined since 1980 along with no real wage growth? It sure was a great Morning in America, if you were in the 1%. All those unsuspecting workers never noticed their real wage stagnating thanks to the hocus pocus of regular inflation. So to maintain their quality of life workers just made up the difference with their credit cards and mortgages.

Enter the totally insane neoliberal idea that financial markets were self-regulating. Add a splash of clueless economists and oblivious politicians and presto you have a predatory financial sector. Giant pool of money, meet increasingly leveraged and desperate workers. This ‘happy’ coincidence is just workers now being charged interest on what really should be their wages, which necessarily ends with massive defaults ala 2008. We wouldn’t expect something as minor as a global financial crisis to wake up people in power to this dynamic though, so none of the fundamentals have changed. I wonder what debt product will be next.

The real Irony is that if the Gipper had half a brain he would have realized that only a few firms looking to expand would seek outside capital. Which is what he was theoretically aiming for with supply side. Most firms just direct profits towards reinvestment as a way to avoid paying taxes. Actually, his ill-conceived tax cut for the rich made it more likely the firm’s elites would take home the profits with a low 30% tax rather than reinvest it as a way to duck the old 70% tax. Then since our Idle rich have so much cash and nothing to spend it on, they buy themselves some politicians locking in the status quo.

Let’s add that all up. He incentivized rich people to disinvest from their companies. Destroying Real growth. Workers kept demand constant because they were oblivious so they just kept on charging it to their credit cards which made GDP look normal even though there was no expansion. We are stagnating now because workers have avoided jumping into another debt bubble. And now, thanks to Wall Street buying Clinton the win over Sanders, we have lost our best hope of repair. So, four more years of stagnation; followed by any old fascist with some free time, who will beat the pant suit off Hillary in 2020.

Did you notice how the Wage share of GDP has flat lined since 1980 along with no real wage growth?

That chart was a very telling thing was it not? But, what I have noticed in my life (I am a 100% disabled vet on a broken income) is that changes to the way inflation is calculated and reported have since the era of Reagan been increasingly understating inflation, so any other calculation that employs historic values for dollars, or that adjusts for inflation, well you can no longer trust them at all.

We should have known how flawed the CPI was at measuring inflation the day the Fed stopped using it in favor of the core PCE. This is another Greenspan gift that keeps on giving. Fed policy required low to no inflation in order for them to lower interest rates in the post 9/11 world, and that requirement has since become an urgent death spiral of ever lower rates into negative bond yields. Even a whiff of inflation would trigger higher rates.

At this point my mind wants to go into three directions at once. Four if you count the horrible things I want to say about followers of Anus Randus. All I am going to say about her and them is that to refer to them as fascists is unfair to fascists.

First, I have a BS Finance from a good private Midwestern university and in the 90’s was licensed by the SEC as a stockbroker, when I retired they had not yet privatized enforcement of securities laws. They had not yet Shanghaied FASB into bifurcating the accounting rules to benefit corporate America allowing them to post fraudulent numbers in the balance sheets, or mark worthless assets at nominal value when in fact they had no market value. So, I speak from a more historical perspective.

There is a reason why classical economics and the textbooks I studied bear no mention of negative interest rates. It is because such a thing is impossible. There is no such thing as negative interest rates. Interest is the price you pay to use other peoples money for a contractual period of time. If the price is zero or if in fact you are paid to use that money then it may be called something but it is not interest. Negative interest is a convenient nickname but it is misleading to those with less than a bachelor degree.

Even in the worst days of the Great Depression or the Weimar inflation or any other economic catastrophe did any monetary authority think paying people to borrow was a good idea. In fact it was actually unthinkable. In fact it was and probably still is in our nation illegal. Because the net effect of negative interest rates is to make a gift of legal tender to the investor class and our laws specifically prohibit the government from making such gifts. In that law there is no exception for “exigent circumstances.” It now appears that making the rich richer and the rest of us poorer is the functional equivalent of exigent circumstances.

Real interest rates can only be calculated over time by discounting the nominal rate of interest on the face value of the note by a REAL inflation rate. So, when we entered the downward spiral into negative rates we must understand that by understating inflation means we are overstating interest rate returns.