Yves here. According to tax maven Lee Sheppard:

Compared to other Western governments, the US government taxes at a very low level, about 18% of GDP…

Trump’s plan, which has huge tax cuts for business and the rich, emphasizes growth. It would inject $4-6 trillion into the economy over 10 years, mostly by means of business tax cuts. This would be supply-side economics, which you can do with your own currency. Two problems:

First, tax cuts would have to be enormous to have any macroeconomic effect on a $16-18 trillion economy. His first plan proposed even larger cuts, and the deficit hawks swooped. Think of it as the tax version of QE. But consumption has fallen, and newly subsidized businesses would still need customers in order for investing to make sense.

Second, even if enhanced growth were achieved, it would not be evenly distributed. US income taxes are progressive. Spending is not, so the system as a whole is not redistributive. And as the individual discussion shows, it would not put a lot more money in the hands of people with a high marginal propensity to consume.

By Antony Ting, Associate Professor, University of Sydney. Originally published in The Conversation

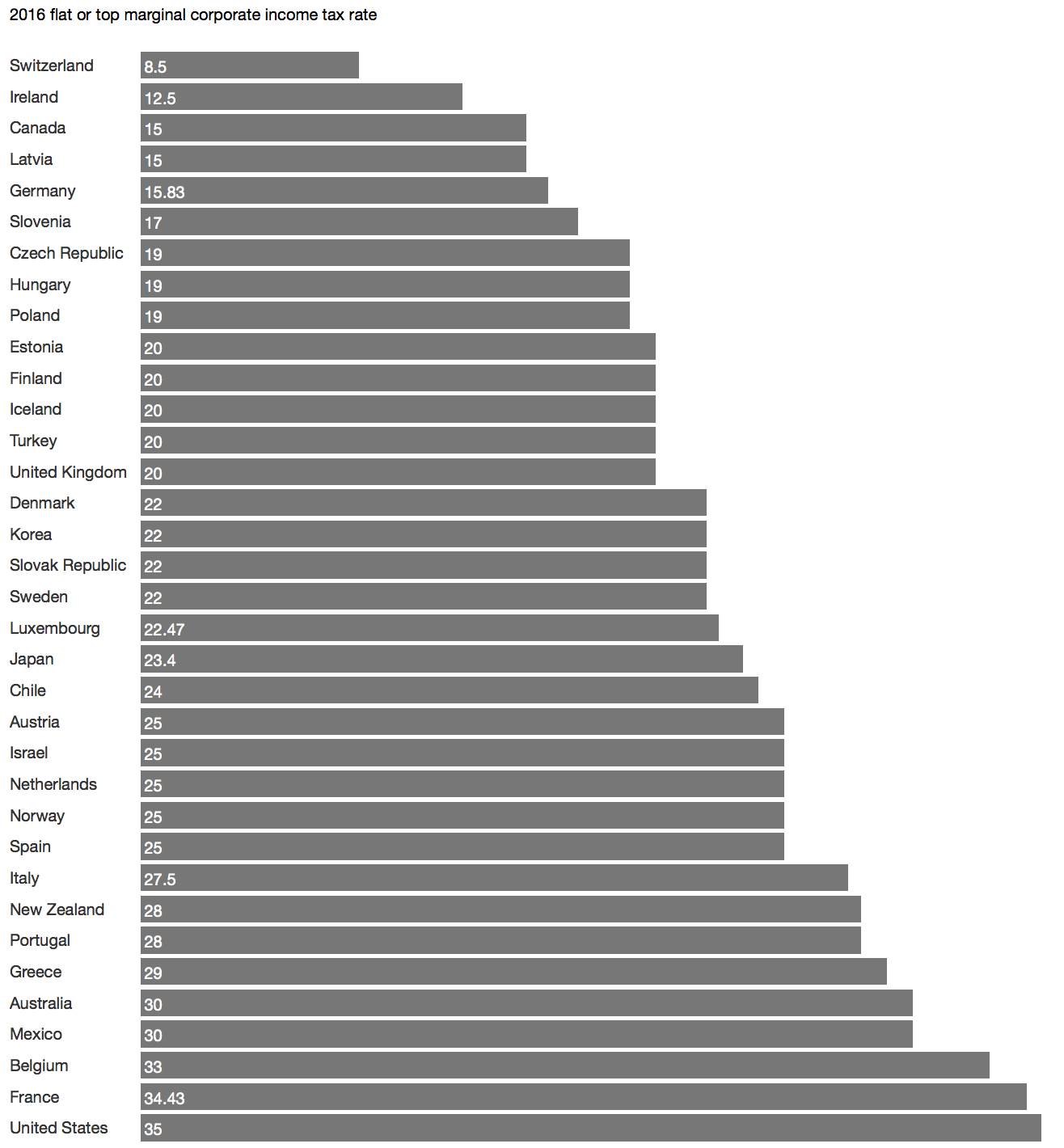

US President-elect Donald Trump made an election promise to cut the US federal corporate tax rate from the current 35% to 15%. A somewhat more modest proposal is under way in Australia. The plan outlined in the 2016-17 budget is to cut the standard company tax rate progressively over 10 years from the current 30% to 25% in 2026-27.

But there are many political challenges governments have to overcome before these reforms may become reality.

A Global Trend

Most countries have been reducing their company tax rates over the last two decades.

The average company tax rate for OECD countries has declined from 32% in 2000 to 25% in 2015. Most of the tax cuts occurred before 2009, and rate reductions slowed down after the global financial crisis. The largest cut over that period occurred in Germany, by almost 22 percentage points (from around 52% in 2000 to the current 30%).

The UK has also been active on this front. Prime Minister Theresa May this week said she wants to cut corporation tax to the lowest among the world’s 20 largest economies.

Britain’s company tax rate was reduced from 30% in 2000 to the current 20%. The government had planned to further reduce the rate progressively to 17% by 2020. This plan is one of the measures to achieve the government’s goal of “creating the most competitive tax regime in the G20”.

Non-OECD countries are equally keen to maintain a competitive company tax rate. For example, China reformed its enterprise income tax system in 2008. A new unified rate of 25% replaced the old 33% rate for foreign investment enterprises and more than 50% rate for domestic enterprises. The government picked this rate after careful and detailed analysis of the prevailing company tax rates around the world for the purpose of enhancing the competitiveness of its tax system.

A Race to the Bottom: Where is the Bottom?

Given these downward trends, many governments are under immense pressure to keep their company tax system internationally competitive. A race to the bottom seems inevitable.

But where is the bottom? A look at the OECD data shows that many OECD member states have a company tax rate below 20%.

While Ireland has its “famous” 12.5% company tax rate, most of these countries are in Eastern Europe. As the UK will also reduce its company tax rate to 17% in 2020, it seems possible that more countries may be tempted to join the queue to cut their company tax rates to 20% or less in the next few years.

Can a Lower Company Tax Rate Reduce International Tax Avoidance?

The Australian government has argued that a lower company tax rate would reduce international tax avoidance, as a reduced tax rate gap between Australia and other countries would mean less incentive to shift profits from Australia.

The tax-avoidance “success” stories of multinational enterprises such as Apple, Google and Microsoft suggest this argument is weak. The fact is that the profits these multinationals shift offshore often end up totally tax-free.

Even a company tax rate of 25% would still present significant incentive for these multinationals to employ tax-avoidance structures. A more effective approach should implement strong anti-avoidance tax law to combat this kind of aggressive tax planning.

Political Hurdles

The revenue impact of the proposed company tax cuts is substantial. In the US, corporate income tax revenue in 2015 amounted to US$344 billion, representing 11% of total federal tax revenue. Cutting the 35% corporate tax rate to 15% is estimated to result in an annual revenue loss in the region of US$150 billion.

In Australia, company tax represented 18% of the total tax revenue of A$446 billion in 2014-15. A cut in the standard company tax rate from 30% to 25% implies an estimated annual revenue loss of more than A$10 billion. Where will the money come from? This is a serious challenge for governments.

A recent OECD report on tax policy reforms begins with this statement:

“In a context of low growth, subdued investment, high unemployment and inequality, tax policy plays an important role in supporting both economic growth and greater inclusiveness.”

A proposal to cut company tax, especially without a corresponding tax cut for individuals, is particularly difficult for governments to sell in this economic environment. The general public appears increasingly reluctant to accept the traditional argument that the economic benefits businesses enjoy due to company tax cuts will eventually flow down to benefit the public at large.

The issue of alternative revenue sources to cover for a company tax cut is particularly difficult to resolve in the US. The absence of a value-added tax in that country, and the formidable political resistance to such a tax, suggests it will be very difficult for the US government to find alternative revenue sources significant enough to compensate for the revenue loss of a company tax cut.

The Sheppard article says corporations are taxed at 18%, but the graph says 35%. Which is it?

No, Sheppard said that US Federal taxes are 18% of GDP:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFRGDA188S

Well, it would level the playing field a little. The smaller companies will benefit, for the big ones it won’t make any difference as they’ll continue using tax-havens to reduce the tax-rate as much as possible. But I suppose that the cut will have to be financed somehow and moving the tax-rate along the ‘laffer-curve’ won’t increase the collected taxes so all in all it is a difficult one.

Maybe financing a cut in corporate-tax-rate by limiting the IP-laws would make sense, might even be possible to do so now that the IP-agreements across the oceans are less likely to happen.

‘Trump’s plan, which has huge tax cuts for business and the rich, emphasizes growth. It would inject $4-6 trillion into the economy over 10 years, mostly by means of business tax cuts.’

This doesnt seem right to me. If taxes are cut by $4-6 trillion, and the government spends $4-6 trillion less, then there is no net change to the economy. simples!

He’s a Republican. He will cut taxes and still spend the same or more and blame black people.

She’s just repeating the PR. Sheppard can be overly terse. Her subpoints dispute the claim.

The most significant sentence in this whole thing is “But consumption has fallen, and newly subsidized businesses would still need customers in order for investing to make sense.”

Or as I like to put it “What part of no freakin’ customers do you not understand?”

Shifting the tax burden from corporations to individuals is not going to provide more customers. If there is already too much production for the number of customers, wouldn’t a company have to be insane to invest in more production no matter how low the tax rate? Only a negative tax rate could spur more investment. In other words the government has to be the consumer of last resort.

Why are we arguing about the details of a policy that makes absolutely no sense at any level?

Of course, the best mechanism for preventing a race to the bottom would be to fix a minimum corporate tax rate as a fundamental element of international trade treaties such as TPP and Ceta. No surprise of course that this doesn’t even seem to have been on the agenda.

Yes, it’s interesting, isn’t it, that all these “free trade” deals & globalization generally all seem to lack genuine & enforceable standards & minimums on such things as international corporate tax avoidance, minimum corporate tax rates, environmental and labour standards (say, the basic workers’right to unionise).

Actually, the world wide race to reduce corporate tax rates, at what ever cost to individual nations, is merely symptomatic of an international Oligarchy openly disdainful of the nations in which (at the moment) they must perforce do business in.

amazing how after all these years the corporate elite can still convince their voters via their politicos that lowering the corporate tax rate across the board is the solution to the problem of economic growth, when there is nothing over the past four decades of reducing taxes on the 1 percent that demonstrates a positive trickle down effect.

Giving more money to the richest members of society does however give them more money to buy elections, buy judges, buy politicians, buy think tanks, universities, media institutions, and change not only the narrative of economic reality but also shift massively the relative power of organized capital vs. backpeddling defensive and largely deciminated and disorganized labor.

So while corporations continue merging and acquiring and lobbying for their additional sources of crony capitalist funding, the average worker bee in the global and domestic economy is left wondering, can I ever get a break from the monotony of working more and more for less and less in the new Golden Age of Rule by the Predatory Capitalism of the 1 percent?

SPOT ON!

I’ve been saying for years now that we need to bring back what is essentially the 1986 tax reform. Permanently. Simple plan:

Harmonize capital gains with labor income –permanently.

Eliminate corp tax altogether — replace that income with import/export tarriffs. This has the benefit of killing the free-trade deals and takes away the major whine of the fiscal conservatives.

Do away with the carried interest loophole.

Based on my 30 plus years as a CPA there is no doubt that a general reduction of income taxes can lead to unpredictable and often counter-productive results. What I have seen work successfully is using high nominal rates with targeted deductions and or credits which force companies to invest. A top tax rate of around 50 percent was applicable for most of the early part of my career and only an economist could miss the fact that the federal government provided a 50 percent (more when state taxes are included) “subsidy” to those brave soles that dared to hire a lot of employees. As the tax rates fell the incentive went away and…well.. who needs employees anyway. Of course what I saw with my own eyes is theoretically impossible so, let’s just keep reducing rates until we eliminate all of the middlemen and all of the money goes to the 1 or so percent. Seriously, during the Regan years when Arthur Laffer was promoting his Laughable Curve a daring Senator asked who the models were designed and queried, What happens if rates are reduced to zero. The answer was believe it or not, taxes would still increase with rates lowered all the way to zero. But what do I know?

I believe you that someone foolishly answered that zero taxes would maximize tax revenues; however, that answer clearly violates the shape of the Laffer curve, which is an inverted “U” (and not necessarily symmetric). According to Wikipedia:

It would seem that the consensus of economists is that the current U.S. corporate tax rate is near the bottom of the range of maximal tax rates. Whether it is near the bottom of the optimal rates is unknown.

The Laffer curve is a clear example of linear (and nonsensical) thinking in a chaotic world.

Approaching either extreme, 100% tax rate or 0% tax rate, the economy collapses, well before reaching the extreme.

The correct discussion to have the the feedback effects of spendable income vs all, including property taxes. High property taxes have the side effect of making home ownership affordable while simultaneously improving schools, roads, and other civic services (such as health care).

If multinational corporations have been largely successful in avoiding tax — who’s been paying it? Who would benefit? Will “S” chapter corporations be included among the winners? What about smaller U.S. based corporations, if any? After the tax cuts will the states follow with more tax cuts and deals for corporations promising to build “jobs” in local areas? What kind of pig does the Trump have in his poke?

if lowering tax rates doesn’t benefit that particular country why is it done anyway? And I’m sure by now it’s common knowledge amongst policy makers that it doesn’t work tp the country’s benefit. So I think Nc should look into the real reasons why they are doing it

Does the chart compare like for like?

For instance, I am pretty sure that, in addition to the Swiss 8.5% federal tax, there are taxes at the level of the canton and municipality, so that all-in tax rates are higher. That is the case for personal income tax comparison stats.

I am also surprised to see German corporate tax so low and Danish corporate taxes lower than Luxembourg ones.

Any insights welcome.

You are absolutely correct. Both Switzerland and Germany are federal countries and accordingly, additional taxes are typically levied at the state or municipal level.

For example, if you have a business in Berlin, you pay 15.825% federal corporate tax (Körperschaftssteuer) as well as 14.35% local business tax (Gewerbesteuer). The minimum business tax rate that a municipality in Germany can set is 7%, but most cities have it at 14% or higher.

Abolish corporate income tax. Treat all income to individuals the same (i.e. eliminate favorable taxes on capital gains, royalties, etc.) Perhaps restructure brackets but, regardless, add further brackets to the personal income tax structure. This will keep income taxes progressive as incomes go up, unlike today, where, at a certain point, to use Warren Buffett’s illustration, bosses start paying less as a percentage of their incomes than their secretaries pay.

Reinstitute inheritance taxes and reform rules for valuing inherited stock.

Get rid of regressive taxes like FICA and FUTA.

Pay for general social programs out of general revenues, i.e. no mre silos like the social security trust fund, the highway fund, etc.

No one will raise taxes high enough on individuals.

Moreover, taxes are about incentives, not revenues. Corporate taxes incentive and decentivize certain activities, as do private tax breaks (the mortgage interests deduction). Get rid of corporate taxes and you lose the ability to use tax as a way to charge for externalities. There’s a whole literature (see Martin Weitzman, or read the section on Taxation and prohibition in this paper http://www.bis.org/review/r100406d.pdf) as to when taxes are a better way to redress externalities than prohibition.

Corporate taxes offer an opportunity (theoretically) to incentivize desired behavior but I’m not convinced they are successful. My anecdotal observation is that large corporations take advantage of these incentives but use them as one more way of looting the system.

Ireland is a case in point (and reveals a big shortcoming in Ting’s post). In Ireland (as well as in the USA) the effective tax rates are typically far below the headline basic rates. To this extent I agree with mad432scam.

In Ireland, R&D tax credits are used as one major way to reduce effective tax rates. A part of the tax scandal in Ireland–though little spoken of in most media–is that the special treatment for the likes of Apple resided in secret letters that agreed how in their unique case certain things would be classified, pre-approved, as R&D expenses–such as paying their subsidiaries in other countries huge licensing fees–effectively allowing income elsewhere to be paid to itself tax free by calling it a licensing fee. Apple’s great tax windfall had little or nothing to do with the fact that Ireland’s maximum corporation tax rate is lower than that of most other countries.

Many countries have versions of bread-and-butter R&D tax credits. My observation in Ireland is that large corporations are the ones who primarily benefit, and they get financial rewards for doing R&D they would have done anyways. They have huge accounting departments to handle the extra paperwork. There are consulting accountants in Ireland who do cold-calling to Irish businesses to help them take advantage of R&D tax credits. At one workshop I was told that a company could improve its way of washing its floors (i.e., nothing to do with its core business) and work out a way (with the help of the consultants) to shape this into a qualifying R&D tax credit.

R&D spend does not do what it says on the box. And increased spending on R&D does not automatically translate into increased revenues from commercialization down the road. That is one of the old wives’ tales many countries have bought into, and this truth was not yet spoken of in polite company in 2010 when Haldane’s article was written.

It’s government spending on R&D projects that it then hands over to corporations (think Silicon Valley) as a part of Deep State activities that drives technical advances that become commercially significant (monopolies, anyone?). It’s not about grass-roots “innovation” at all.

R&D tax credits are just one example. Ting’s post also ignored the capital gains tax issue, which shouldn’t be ignored even though he’s focusing on corporation tax. As long as capital gains income is taxed preferentially, the high-wealth executives/shareholders/investors who benefit most downstream from lower corporation tax rates will continue to use their excess wealth for non-productive speculation that hurts the 99% the most and adds costs and risk to the entire productive economy.

The nominal 35% rate is too high for small business, but there is too many deductions for big business. Barring an embrace of MMT and/or the sudden death of everyone who ever set foot in the Peterson Institute we should be looking at making corporate taxes progressive and set a minimum effective tax rate. That would encourage more small business, which are not getting started nearly as much as they used to. We already have one of the lowest corporate taxes.

https://www.janus.com/insights/bill-gross-investment-outlook

“creating the most competitive tax regimes” Ah yes, “competitive” one of the great red-flag words, right down there with smart, disruptive, innovative etc. I wish someone would send people such as May to restaurant when they’re starving, charge them $200 and bring them a plate with five grams of dry moldy bread, a cup of scummy water and when they questioned the meal tell them proudly “Yes! We offer one of the most competitive dinners available in any restaurant”

The tax rate may be 35% but the large corporations pay less than third of that. I remember reading a report showing that the top 65 companies actually paid between 8% and 10% and many paid nothing at all.

And that, as I like to point to conservatives who love to push low corporate taxes, means the money not paid by corporations has to be made up by money from individual taxpayers.