Yves here. Uber’s continuing losses, with no near-term prospect of reversal, seem to be denting the Silicon Valley darling’s carefully cultivated image of invincibility. For instance, in Uber and Airbnb business models come under scrutiny, the Financial Times described how both companies are facing more and more effective opposition to their cavalier rule-breaking. In a Slate story, Why It’s Getting Harder for Uber to Break the Law, which tellingly was reprinted by Business Insider, Henry Grabar flagged an issue that Hubert Horan has stressed in his Uber series: that Uber is not a software company, but an urban transportation company. And as the company moves more and more in the direction of owning assets, like driverless cars and autos it leases to drivers, the more it becomes subject to real word regulations.

By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan has no financial links with any urban car service industry competitors, investors or regulators, or any firms that work on behalf of industry participants

Latest Leaks Provide Further Confirmation of Uber’s Bleak Financial Performance

Part One of Naked Capitalism’s Uber series laid out all of publically reported data about Uber’s Operating P&L results between 2012 and the first half of 2016. Only EBIDTAR contribution data was available for this entire time period; true GAAP profitability data was only available for the year ending September 2015 when Uber lost $2.0 billion with a profit margin of negative 143%. Through the end of 2015 Uber’s EBIDTAR contribution margin was consistently a bit worse than negative 100%. While this margin improved to negative 62% in the first half of 2016, all of the improvements were explained by Uber’s cuts in driver pay.

Uber EBIDTAR contribution numbers for the third quarter of 2016, leaked to the press on December 19th[1], show yet more bleak results. Third quarter EBIDTAR was worse than negative $800 million (no exact result was disclosed). Media sources said that Uber expected fourth quarter EBIDTAR contribution again to be negative $800 million. This would produce a full year 2016 EBIDTAR contribution in the range of negative $2.8-3.0 billion, meaning that true GAAP losses for the year would easily exceed $3 billion.

As with the first half 2016 data, a small improvement in the EBIDTAR contribution margin was entirely explained by further cuts in driver compensation; there was no evidence Uber had improved operational efficiency or was getting passengers to pay higher fares.

These third quarter results (and the fourth quarter projection) reaffirm the major conclusions of Part One of the Uber series – Uber’s operations and growth has depended on unsustainable, multi-billion dollar investor subsidies, and in Uber’s seventh year of operations there is still no evidence of the strong, steady P&L margin gains needed to show a clear path to breakeven, much less the roughly $5 billion in annual P&L improvements needed to generate meaningful investor returns.

One of the two reporters that published the leaked data (Efrati) argued that “Uber’s departure from China in the middle of the quarter helped slow the growth rate of its losses” and that the losses “reflects its increased investment in areas like self-driving car technology and mapping.” Neither of those claims is credible. Both impacts of the sale of Uber’s shareholding in the failed Uber China venture (which include a multi-billion dollar gain from Uber’s new shareholding in Didi Chuxing) and investments in speculative future ventures like driverless cars would impact cash flow and balance sheet statements, but not 2012-16 quarterly operating P&L statements, and it is not clear that the reporter understands the difference.

Stephen Levitt’s Bogus Claim that Uber Creates Massive Consumer Welfare Benefits

The first four parts of Naked Capitalism’s Uber series (Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four) focused on the question of whether the growth and eventual industry dominance of Uber has (or could in the near future) create sustainable improvements in overall economic welfare. Neither the bleak P&L results of any other single piece of evidence is isolation could answer this question, but the range of evidence presented consistently supported the conclusion that Uber had, and would continue to reduce welfare.

Uber is a substantially less efficient producer of urban car services than the incumbents they have been driving out, so its growth reduces overall industry efficiency. All of Uber’s apparent price and service advantages depend on unsustainable investor subsidies. Uber has not introduced any significant efficiency or product breakthroughs and lacks the scale economies that could quickly generate billions in P&L improvements, and all of Uber’s behavior suggests it fully understands that it could not provide returns to investors without achieving exploiting significant levels of welfare reducing anti-competitive market power.

In isolation, the lower taxi fares some consumers may have received thanks to Uber’s multi-billion dollar subsidies do not constitute a consumer welfare gain because those subsidies are unsustainable and are explicitly designed to drive more efficient producers out of business and create artificial market power, which would massively offset any short term welfare gains. Subsidies supporting the pursuit of industry dominance can only enhance long-term economic welfare if the dominant company can produce service at significantly lower cost/higher quality than the displaced incumbents, and if the dominant company continues to pass a significant share of those efficiency gains on to consumers. At this point there is absolutely no public evidence that Uber will ever be able to offer consumers lower prices and increased service on a sustainably profitable basis.

Stephen Levitt, a senior economics professor at the University of Chicago, and co-owner of the “Freakonomics” media venture vehemently disagrees. He co-authored an article (further publicized through his various blogs and radio programs)[2] claiming that Uber generated $6.8 billion in consumer surplus in 2015.

Given hard evidence of Uber’s inferior efficiency, disastrous financial performance and aggressive pursuit of quasi-monopoly industry dominance, how could an economist find evidence that the entry of Uber into the market has not only made consumers better off versus an industry dominated by traditional operators but found consumer gains of such an enormous magnitude?

The first clue is that Levitt is an unabashed Uber supporter who admits he “loves Uber” and describes them as “a phenomenally successful company” even though they had a negative 149% operating margin during the period he studied (the first half of 2015). Levitt claims “Uber embodies what economists believe should happen with the labor market,” is openly rooting for Uber “to destroy the old-school taxicab and private-car industries” and thinks the finding of the paper will be “the hammer with which I could smash all government resistance to Uber.” The second clue is that the analysis was financed by Uber, and two of his co-authors are senior Uber officials. This was not the result of unbiased research by an independent academic.

The third and most important clue is that there is no data or analysis in the papers that compares how consumers fared since Uber’s entry with how they fared before Uber entry (or compared consumer prices and service between markets that does and does not serve or made any other type of comparison). Nor is there any data on any of the issues discussed in the Naked Capitalism series that are critical to an understanding of whether post-Uber marketplace changes have (or could eventually) improve consumer welfare, such as evidence of major efficiency advantages or scale economies that would allow it to produce service at lower costs than existing competitors, or evidence that it could profitably offer lower prices and better service than incumbents in competitive markets.

So there is absolutely nothing in the paper that would allow anyone to conclude that consumers are better off with an Uber dominated industry than they had been with an industry dominated by the old-school taxicab and private-car industries, and there is nothing in the paper that justifies the conclusion that the headline “$6.8 million annual” number represents a consumer gain of any kind.

The $6.8 billion estimate had been derived from Uber moment-of-sale data from Uber’s four largest markets during the first half of 2015 that showed when customers who wanted immediate cab service were given surged prices (which could be 10 to 500% higher than baseline fares), and whether or not service at the surged prices was accepted or refused. Levitt then estimated a continuous curve across the full range of surged price options and calculated customer price elasticity from that curve. Levitt calculated the “consumer surplus” gap between accepted prices and the higher prices they would have been willing to accept as a consumer benefit that Uber had uniquely created, and the total $6.8 billion was estimated by extrapolating the “surplus” from his half-year 4 city sample to full year 2015 traffic in all US markets.

Unfortunately estimates of the consumer surplus of Uber users in isolation does not and cannot measure incremental changes to consumer welfare across the entire market. It does not measure how consumers fared before and after Uber’s entry, and only looks at an artificial subset of consumers. Consumer welfare can only improve if a marketplace change provides consumers with sustainably lower prices and/or superior service. Uber has higher average prices (21% of all trips in the study sample had surged prices, while traditional operators have no price surges), so Levitt and Uber are making the absurd claim that the company with higher average prices benefits consumers more. And the paper makes no effort to explain why its “consumer surplus” approach that apparently had never been used before in published academic economic studies would provide superior measures of changes to consumer welfare than traditional approaches.

Consumer surplus exists in every market, because even with variable pricing systems controlled by fancy software, companies like Uber offer a single price in each selling situation (Uber offers the same surged price to anyone requesting a car at a given time in a given geographic zone) and almost all of the people who purchase at that price would have also purchased at a slightly higher price. Consumer surplus would only disappear if companies read the minds of each individual consumer and then block them from accessing prices available to other, more price sensitive consumers. The fact that the Levitt/Uber consumer surplus estimate is a really big number is strictly a function of their calculation that demand is highly inelastic. Highly inelastic demand means people will often be willing to pay more than published prices (ergo much more “consumer surplus”); elastic demand means traffic falls faster when prices rise (so much less “consumer surplus” potential).

But all of the Levitt/Uber data massively overstates demand inelasticity by measuring “moment of sale” consumer decisions, instead of medium/long-term responses to price changes. The Levitt/Uber data are measuring people who are already committed to travel as soon as possible, and have started the ordering process — people who will always be highly price inelastic. But data showing many will accept a 25% price surge at that moment tells you nothing about how they would respond to longer term price changes. If all fares (peak and off-peak) went up 25% you would see a much bigger reduction in taxi usage (e.g. much higher elasticity) than the “moment-of-sale” response to a 25% surge would suggest.

The analysis is further biased because 75% of all the data reflects the behavior of people who are frequent Uber users in four of the wealthiest cities in America (NY, SF, LA, Chicago). These are the people least likely to consider alternatives when faced with surged prices, and it is highly unlikely that their willingness to pay higher prices reflects the price sensitivity of the total, nationwide market for urban car services. Large results from Levitt’s methodology cannot support conclusions about changes to efficiency or welfare gains because they are primarily measuring changes in customer price elasticity. Walmart’s growth was driven in large part by its efficiency/productivity advantages over traditional department stores. But if you applied Levitt’s approach to Walmart it would tell you consumers were significantly harmed, because Walmart’s customers are more price sensitive than typical department store customers (since Walmart’s customers include many more people with lower income, the gap between prices and the demand curve would be smaller). Long-term demand of the total market is much more elastic than “moment-of-sale” demand from frequent Uber users in wealthy cities. The Levitt/Uber paper cherrypicks data from the segment of the urban car service market with the least sensitivity to price, in order to artificially generate the huge “consumer surplus” number highlighted in their conclusion.

Why Would a “Serious” Academic Produce an Indefensible Analysis Like This?

Why would a prominent economic professor from a prominent university actively publicize that his research had identified “the impact that Uber’s introduction has had on consumer welfare” when there is absolutely nothing in the data or analysis that even attempts to measure consumer welfare impacts? Presumably the answer involves some combination of personal ideological affinity (his personal preference that all legal regulatory obstacles to Uber’s success be smashed, along with all existing “old-school” industry participants) and financial incentives provided by Uber for attaching his name to what was largely an internal Uber study. Note that none of the reasons Levitt gives for loving Uber and rooting for its eventual industry dominance have anything to do with increased consumer welfare; Levitt participated in the study because he was hoping to find a welfare justification for his enthusiasm. Levitt’s description of a company that lost $2 billion in 2015 as “a phenomenally successful company” demonstrates Levitt’s willingness to ignore compelling evidence inconsistent with that enthusiasm.

Levitt would have also had reasonable grounds to assume that there was little risk that the poor quality of his work would have ever been attacked by fellow academics (many of whom undertake private consulting projects like this, where results are not subject to any type of academic peer review) or journalists (who had never examined these issues independently and in any event would be highly reluctant to openly challenge a famous academic).

Levitt took some steps to protect himself in case knowledgeable people read his paper carefully and pointed out some of the serious flaws. His radio discussion emphasized that his role on the Uber project focused on the methodological issues involved in translating raw Uber data into the demand curve and elasticity estimates.and claimed he was the first person to ever actually develop a demand curve from industry data.[3]

Levitt actually acknowledges that the analysis does not meet academic standards. Both the academic paper and the supporting Freakomics publicity acknowledge that the questions being addressed require long-term elasticity measures, and that the “moment-of-sale” elasticity measures actually used are inappropriate[4]. Including this admission in a peer-reviewed academic paper would have been tantamount to saying “stop reading here and ignore all conclusions presented because the data doesn’t support them.” The ethical/professional problem is that even if Levitt buried qualifying statements about the elasticity measures deep in the article text, he failed to ensure that the highlighted primary conclusions based on those elasticity measures (creation of $6.8 billion in annual consumer benefits) were qualified in any way.

Despite these questions about Levitt’s intellectual integrity, it is more important to understand why Uber hired him to serve as a paid advocate, and the larger process by which Uber sought to publicize an “Uber creates billions in annual consumer benefits” meme without actually having any legitimate evidence that it did. Had this paper been produced entirely (instead of largely) by internal Uber staff, it would have been impossible to get the claims published in mainstream media outlets. By paying Levitt to put his name on the study (and publicize it through his blogs and radio programs) Uber could create the appearance that the $6.8 billion benefit claim resulted from independent analysis that met academic standards, and knew that no one in the media would scrutinize (much less challenge) work endorsed by a famous U of Chicago professor. Regardless of any nuances or qualifications buried in the paper (that no one would read) the paper created a valuable soundbite (famous U of Chicago economist says Uber creates $6.8 billion in annual consumer benefits) that Uber could circulate widely.

Uber did this by getting a series of pro-Uber columnists to publicize the highlight benefit claim through uncritical articles about the Levitt/Uber paper in a range of respected media outlets including the Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Bloomberg and the New York Times.[5] Each article falsely portrayed the $6.8 billion claim as “consumer welfare” benefits as if the paper had compared the welfare impacts of Uber versus traditional operators. Tyler Cowen, a well-known libertarian blogger (and active Uber supporter) who writes columns for Bloomberg and the New York Times, misrepresented the $6.8 billion number from the paper was the “social value” of Uber, and reflected the economic loss society would suffer “if Uber simply went away.” Cowen highlighted how the finding illustrated how “consumers gain from lower prices from a new service” even though neither he or the Levitt study had any evidence that Uber passengers currently pay lower average prices, or would in the absence of massive subsidies. Cowen claimed that this evidence of huge consumer benefits justified his view that current industry competition was “a fight between progress and protection.”

A Wall Street Journal columnist claimed the study proved that Uber had created net economic welfare gains because “U.S. consumers alone are reaping billions of dollars a year in benefits, far greater than the losses borne by taxi owners” even though there was nothing in the study that purported to analyze those tradeoffs. That columnist highlighted the accomplishment of estimating a “demand curve” while ignoring the caveat that the demand curve estimated was totally inappropriate for the conclusions drawn. He also insisted that Uber illustrated how “[t]he free-market system has long ensured goods providing very high consumer surplus are cheap” without explaining how a company that lost $5 billion in the last two years could serve as an exemplar of the free-market system. A Forbes columnist falsely claimed that the result showed “that Uber is indeed making us all richer.” He highlighted the huge gap between price and willingness to pay, and facetiously attacked Uber for not raising prices more aggressively, but ignored the long-run versus moment-of-sale elasticity issues that the paper had pointed out. The New York Times published a nationally syndicated columnist who claimed the $6.8 billion estimate was based on demonstrated “economic theory” without bothering to explain what that theory was, or noting that Levitt’s methodology had never been used in any prior academic analysis of consumer welfare impacts. He tried to argue that these benefits somehow offset the growing public evidence of huge Uber losses, and failed to disclose Levitt’s “analysis” had been paid for and co-authored by Uber.

Thus the original Uber sponsored study produced a big number it could publicize ($6.8 billion in annual consumer benefits) and a famous academic name it could attach to the study to create the false impression the number resulted from rigorous, independent analysis. The secondary sources increased awareness of the headline claim, and generated new pro-Uber claims (huge social of value of Uber thanks to lower prices, victory of progress over protection, Uber making us all richer, victory for the free market) that were not based on any data or analysis.

Uber’s Use of False Consumer Benefit Claims Is Not New – Consumers Did Not Benefit When Taxi Medallion Values Collapsed

The Stephen Levitt endorsed $6.8 billion consumer benefit claim was not the first time Uber attempted to manufacture pro-consumer propaganda claims out of thin air. One of the first themes in pro-Uber propaganda is how consumers had been directly harmed by high taxi medallion values, and that by destroying that value Uber has generated huge benefits for consumers. Travis Kalanick has often claimed in 2012-13 that Uber was fighting “the taxi medallion evil empire” and in late 2016 Levitt was still claiming the only people harmed by Uber have been taxi medallion holders. To quote just one of many possible examples, an unabashedly pro-Uber article by a Washington Post writer claimed that “In exchange for all of this regulation, taxis have for decades held a government-backed monopoly. At the center of that bargain — and the debate over what form of transportation best serves the public — is the medallion…Uber counters that medallions have created a cartel that operates for its own benefit — and not in the best interests of the public.”[6]

Allowing tradeable medallions is bad regulatory policy and will not be defended here, but the Uber claim that medallion trading values represents wealth extracted from consumers, and that consumers recaptured that wealth when Uber destroyed those trading values[7] is utter nonsense, and none of the many people making that claim ever provide any supporting evidence.

The Uber claims conflate two entirely separate issues – should city governments be allowed to limit the total number of taxi operating licenses issued, and should that public license to operate a car service on city streets be transformed into a tradeable private property right, as has happened with broadcast licenses, water rights, landing slots at congested airports and other private uses of limited public resources?

The first question is debatable; the historical justification for limiting market entry via license caps was that the taxi market is limited, faces a severe peaking problem and marginal peak capacity costs much more than highly-utilized average capacity. Entry limits mean all drivers get a somewhat fair share of peak and off-peak hours, and reduce the risk that higher-cost cream-skimming marginal entrants make it impossible for anyone to make any money. There is also evidence that some cities loosened or eliminated license caps without undermining industry viability, so a simple “entry limits always good/bad” conclusion probably can’t be drawn.

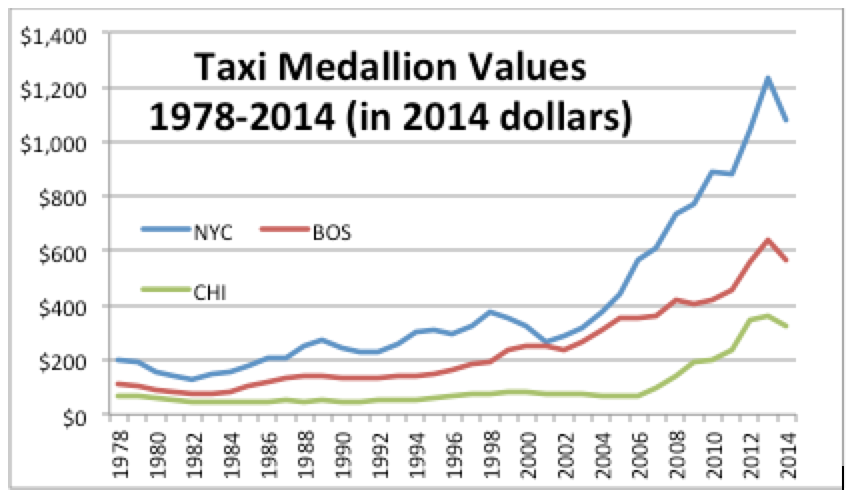

But the tradeable medallions that are the central focus of the Uber claims only had significant value in three cities — New York, Chicago and Boston.[8] There was never any significant difference in taxi fares, service levels or driver wages between those three cities and any other large US cities, and there is absolutely no evidence of any adverse consumer impacts concurrent with the recent run-up in medallion values. Just as fluctuations in broadcast license values had no impact on advertising rates, and airline fares did not fluctuate with slot values at LaGuardia or O’Hare, medallion values did not represent wealth transferred from taxi consumers.[9]

The “medallions extract wealth from consumers” argument is based on the false claim that trading values are a direct function of the stream of future profits a medallion holder might earn. If the claim was true, one would see long-term medallion value fluctuations in line with industry profitability and supply/demand conditions, and would see major adverse consumer impacts in cities with high medallion values, compared to cities with lower values and cities that did not have medallions. In reality, these three cities established medallions in the 1930s, but values did not begin growing until the 1960s.[10]

The huge recent inflation in medallion values is totally explained by changes in speculative financial markets. When returns in most classes of low-risk investment fell in the early 2000s (and fell dramatically after 2008) investor demand for medallions soared.[11] This created massive windfall profits for people who happened to have acquired medallions in the past, but neither the initial rise nor the subsequent collapse of these values had any direct impact on consumers.

Why would Washington Post reporters falsely claim that Uber’s destruction of medallion values had created huge benefits for consumers? For the same reason that University of Chicago economics professors would falsely claim that the response of frequent Uber users to surge pricing proves that Uber has created massive consumer benefits. Both were willing participants in well-designed Uber PR propaganda programs, and were more interested in helping promulgate Uber’s desired narratives than they were in presenting analysis based on legitimate data.

In both cases Uber had developed a narrative about wonderful benefits Uber had created, featuring large dollar impacts that would get attention, and structured in ways that would ensure the business press would not seriously scrutinize the legitimacy of the claims. The false surge pricing/consumer surplus claim was protected from scrutiny by the use of a famous “brand-name” economist. The “medallion value stolen from consumers” claim handed the media an appealing narrative pitting the heroic, cutting edge innovators from Uber against a clearly defined enemy (the corrupt “taxi medallion cartel”) that provided terrible service and that no one in the press liked. Like any good propaganda campaign shifting the discussion to a simplistic good vs evil narrative meant the media did not have to investigate any of the actual competitive industry questions – did Uber actually have any powerful, efficiency enhancing innovations, could its business model actually solve any of the service problems Manhattan Yellow Cab users faced, or did it have any advantages in the 95% of taxi markets that are totally unlike Manhattan and never had tradable medallions, or could Uber actually make money in a competitive environment. Once Uber can get sympathetic columnists at other mainstream outlets to repeat the claims, they gain broader credibility and acceptance, and that fact that the original analysis was intellectually indefensible and had never been vetted by any independent experts is forgotten.

_____________

[1] Efrati, Amir, Uber’s Loss Decelerates, Reflecting China Exit, The Information, 19 Dec 2016; Newcomer, Eric, Uber’s Loss Exceeds $800 Million in Third Quarter on $1.7 Billion in Net Revenue, Bloomberg, 19 Dec 2016. Efrati claimed the P&L data was driven by Uber’s exit from China, but Newcomer did not.

[2] Cohen, Peter, Hahn, Robert, Hall,Jonathan, Levitt, Steven and Metcalfe,Robert Using big data to estimate consumer surplus: The case of Uber. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016. Dubner, Stephen J., Why Uber Is an Economist’s Dream, transcript of Freakonomics Radio discussion between Dubner, Steven Levitt and Jonathan Hall 7 Sep 2016 http://freakonomics.com/podcast/uber-economists-dream/

[3] This claim might come as a surprise to Sveriges Riksbank, who awarded the 2015 economics Nobel Prize to Angus Deaton for work that prominently featured demand curve estimation. Or to the thousands of industry analysts whose estimation of demand curve slopes and elasticities are critical to decisions about pricing and capacity.

[4] [What’s in the paper]“..is actually not the demand curve I wanted to estimate at all. It’s the only one I could estimate but not the one I really wanted. So for public policy, like in deciding how to regulate Uber, for instance, the demand curve you’d love to have is what we call a long-term demand curve.”

[5] Cowen, Tyler, Computing the Social Value of Uber. (It’s High.), Bloomberg 8 Sep 2016.; Creighton, Adam, Uber’s Pricing Formula Has Allowed Economists to Map Out a Real Demand Curve, The Wall Street Journal, 19 Sep 2016; Worstall, Tim, Freakonomics’ Steven Levitt On How Inefficient Uber Really Is, Forbes, 20 Sep 2016 (the “inefficiency” was the higher prices Uber could have charged, but out of the goodness of their hearts, did not); Beales, Richard, Uber’s Value to Riders Is Clear. To Investors, It May Prove More Elusive, The New York Times, 22 Dec 2016. Beales’ piece was nationally syndicated by Reuters’ “Breakingviews.”

[6] Badger, Emily, Taxi medallions have been the best investment in America for years. Now Uber may be changing that, Washington Post Wonkblog, 27 Nov 2014.

[7] “As [Kalanick] notes, in New York there are 13,000 taxis with medallions that trade for close to $1 million, implying a very profitable cash flow from fares.” Kesler, Andy, Travis Kalanick: The Transportation Trustbuster, Wall Street Journal, 25 Jan 2013. “Doesn’t the high-value of medallions (over $1mm in some markets) implicitly prove that the market is undersupplied and that prices are above true market clearing prices?” Gurley, Bill, How to Miss By a Mile: An Alternative Look at Uber’s Potential Market Size, Above The Crowd, 11 Jul 2014. Gurley is a major Uber investor.

[8] In New York, only street hail (Yellow) taxis have tradeable medallions; “for hire” dispatch cars and limousines do not. Miami, Philadelphia and Atlanta sanctioned medallion trading markets in the 90s but prices were always below $100,000; San Francisco reclaimed medallions as city property in 1978. Some other cities appear to turn a blind eye to small scale black market medallion trades, but true exchange markets never developed.

[9] A study of taxi regulatory practices in the U.S. commissioned by the San Francisco Mayor’s Office found no relationship between license tradeability and price or service levels, but rejected any proposal to increase license tradeability unless new regulations ensured that any rents created were shared with drivers. Lam, D. Leung, K., Lyman, J. The San Francisco Taxicab Industry: An Equity Analysis. Richard & Rhoda Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley, (2006) 10-15.

[10] Historical medallion values compiled from multiple sources including New York Taxi and Limousine Commission data; Boston Mayor’s Office of Transportation, Boston Taxi Study, 4 (1978); monthly reports of medallion sale prices in Chicago Dispatcher Magazine; Barlett, A. & Yilmaz, Y., Taxicab Medallions—A Review Of Experiences In Other Cities, prepared for the Government of the District of Columbia (2011); San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, Managing Taxi Supply, prepared by Hara Associates (Apr 2013); Badger, supra.

[11] Prior to 2004 medallion prices closely tracked general financial market indices such as the S&P 500. Dhar, Rohin, The Tyranny of the Taxi Medallions, Priceonomics, 10 Apr 2013.. The post-2004 increase was heavily influenced by the specialist financial firms that had long provided medallion-collateralized loans to cab drivers. Malik, N. A Bet on the Rising Value of Yellow Cabs, Barrons, Jun 2007; Mead, C., Taxi Licenses as ‘Cash Cows’ Bolster Medallion Financial Shares, Bloomberg Financial News, 16 Nov 2011.

Spoke with cabbies in Abq and NYC recently, they all said the medallion business would be dead by the tend of the year if nothing changes.

The Abq drivers also said that if the medallions could get exclusive access to the airport arrival traffic, that would sustain them sufficiently. The NYC cabbies I spoke with were non-committal on that.

Black cab drivers in London have told me that they have no worries about uber. The uber drivers use sat navs and cannot cope with the congestion.

Yes, ditto. I bring this subject up with every Black Cab driver (poor chaps — and the odd chap-ess too, but there’s not many of them!) who is talkative, and that’s the majority of course (trying to get some to shut up is more of a problem).

Uber’s model does not translate to every locality and central London is an example of why. Sat Nav is highly unreliable in London’s narrow streets where the growth in mega-high rise towers adds to the issue of losing GPS on a too regular basis. So Uber drivers without “the knowledge” struggle when the Uber app gives up on providing navigation. Lack of true route and traffic conditions knowledge means Uber drivers don’t know when to avoid certain main roads (e.g. if a bridge is closed or there’s roadworks). Plus you can wait ages for a free Uber, all the while you can be passed by several Black Cabs with their lights on.

Throw in the mayor’s tightening up on insurance, criminal record checks and language tests for drivers means that many chancers are giving up before they get caught breaking the private hire rules. The recent Employment Tribunal ruling said that Uber drivers are “workers” is another nail in the coffin — Uber is appealing but the Tribunal’s judgement is incredibly detailed by the standards of these things and looks to me like it is purposely written to be secure enough not to be overturned even if Uber goes to the Supreme Court (and it is not a given they will get leave to do so; the law is very well settled on the live issues in the case).

So yes, most cabbies see Uber as a fly in ointment not a serious threat.

Have people seen the same issue with GPS (SatNav) while driving around other big cities? Like NYC? Chicago?

-GPS (SatNav).

at times yes, GPS does cut out (but it ‘feels’ that cell phone inertial navigation and Google’s wifi geolocation has gotten better over the years).

Another issue is that GPS doesn’t work in tunnels and viaducts. Chicago has an underground network of roads downtown that confuses GPS AI or drivers who get confused by the routing that GPS provides.

Also GPS AI at times provides screwy routings for no good reason—or adds a few miles to literally save 1 or 2 minutes.

And to be blunt, if one needs to be using GPS (apart from getting real-time traffic info/re-routings) in your hometown (especially in the business district/tourist areas), you should not be doing this.

citation I’m an ex-Uber driver.

I suspect Uber adds those few miles to “save time” also adds to their self-serving bottom line. When I explain to riders the fact that I must drive a couple of miles out of the way to get to a free way where I am “taking the fastest route possible,” it is adding dollars to their fare. So, are they in a hurry? I’ll take the freeway (which is never faster during rush hour), otherwise, going cross-town in a direct route will save them money.

GPS is often buggy as you state, and the problems it has in more upscale neighborhoods would make it impossible to use a driverless car. 1) how will the driverless car punch #1234 to get into a gated community? Is Uber expecting these people to walk a mile to get to the gate? Their not thinking these things through is telling. 2) A rider dropping a pin while in the back of their home will regularly result in the rider being directed to the street behind their home. How will the driverless car remedy that error? 3) More important, the driverless car will guarantee the interior of the car will be trashed on a regular basis. From minor littering, to tracking dirt and mud onto the floor, up to vomiting and saying “bye Felicia” leaving the mess for the next customer to discover. Uber says, “They will just cancel and order another car.” How many more well-heeled customers would ever want a repeat of a vomit-spewed car? This seeming refusal to deal with the warts the system now has tells me how uncommitted Uber is to it’s business model.

Eventually, Uber will only be used by low-income riders who will tend to tolerate this nonsense, except instead of being picked up at their front door, Uber will require they have their toes on the curb at bus-like pickup locations. But how will THOSE riders prove to Uber’s driverless cars that they are legitimate passengers and not freeloaders? If the latter hops on board, how will the driverless car get rid of them? The scenarios are hilarious. Which also tells me Uber hasn’t taken the time to think this out.

Lastly, the paper by the Freakonomics disingenuous likely ignored the larger issue: currently, it is the driver who provides the asset of their car as well as gas and maintenance, which is not small considering the hard use these cars face. With the price cuts Uber has devolved toward, most drivers make less than minimum wage and the riders self-righteously do not tip thanks to Uber’s insistence it isn’t necessary. This results in drivers being treated rather like modern-day slaves.’

Uber is racing to the bottom and it’s taking the investors with it.

The “urban canyon” effect on satellite navigation systems can easily show up even in smaller cities depending on the luck of the draw of where in the sky the satellites are at a given moment. Positioning requires some kind of view of four satellites, though you can still hold a fix with a signal bounce or two. Japan is even launching four satellites that wobble in their orbits above the country (QZSS) to augment SatNav performance by having more overhead satellites available above all the skyscrapers.

I have connection problems driving around south-western Connecticut for all its’ hills, valleys and deep glades!

Still depend on book and folded maps to find the “best” routes from here too there. Following a robots instructions is frought with missed possibilities and, typically, a few errors.

Live in upper Manhattan. LaG under construction, so just to make double-sure I caught a can’t-miss flight I scheduled an Uber pickup for 5:00 am, since in NYC you can’t legally schedule a pickup by a regular cab. (1) No cab at 5:00; instead, that’s when the app placed the call (guaranteeing it would be late). (2) My exact pickup address was specified, but (as you say) the pin was to the back of the building. Unfortunately, the road (a parkway with of course a completely different name and no building numbers) to the back of the building is 300 feet down and at least 10 min. away due to exit placement and one-way arrangements. Clueless driver mindlessly followed the GPS to the unnumbered parkway with nowhere to stop, then called and wondered where I was. Told him I was at the pickup address and I’d take the subway instead. Headed to subway intending to get to a major stop and catch a street cab but miraculously spotted a regular cab dropping someone off in front of the subway. Hopped in, told the driver which airport, terminal and airline and was there in less than 30 min.

If the regular cabs only had a decent app (e.g., scheduled pickups and universal cab coverage) they’d mop the street with Uber.

In Brazil we have ’99’ (previously named ’99taxis’), which arrived earlier than uber and does the exact same thing.

To counter uber’s lower prices, they started offering discounts to users who ordered a cab through the app. I’m not sure if they are subsidizing fares, but they seem to be in good shape. In fact, they just got U$100mi in investiments from Didi (China).

When you know your pin-dropping will send the driver to a different street than your actual pickup address (the gps apps are adamant in taking you to the closest area where it senses your phone when you drop the pin), why don’t you text the driver with your specifics? To call the drivers “clueless” says a great deal more about you than it does about them.

I always thought that Mr. Freakonomics was a shill.

Better than that. Freak on omits is a branded shill franchise.

The S.H.A.M.E. project exposed Steven D. Levitt:

http://shameproject.com/profile/steven-d-levitt/

I wonder whether the following situation will lead to scrutiny as to the insurance situation of Uber drivers. However, this was not the first crash with a fatality that an Uber car was involved in in CA, and have not seen any reports that car insurance companies question the insurance situation of Uber drivers.

http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-lapd-officer-killed-new-years-crash-20170101-story.html

I have no actual evidence of this (nor does anybody else, I imagine – just as Uber prefers), but I have to believe that a substantial number of Uber drivers, aside from the Uber Black drivers, are improperly insured. Following up on and punishing this probable lack of coverage would likely cripple the company in most markets. Yet another example of the Uber model of corporate citizenship: let your employees incur all the risk and get all the blame when things go wrong.

‘aside from the Uber Black drivers, are improperly insured.’

easy solution—don’t think about tail risk. everyone rides in Lake Woebegone.

Local media especially runs on press releases masquerading as news. Insurers don’t want to be the people denying coverage while they deny coverage, so they won’t be pushing fluff stories.

Very likely true. I have seen and heard insurers advertising special ride share insurance products, but have not read anything about their adoption. I would wager the insurance industry has some interesting statistics on accidents and claims denial because of improper insurance.

I am no great fan of the London mayor, but his get-tough approach to Uber drivers with regards to having the correct insurance police is something I support. His consultation which will almost certainly lead to a regulation to the effect that Uber drivers must display their policy document in the vehicle indicates that he — rightly — believes that many are currently getting away with using “social, domestic and pleasure” (as it is known here) non-commercial coverage.

Just out of interest, I had a quick go at getting “hire and reward” insurance in my Home Counties (London commuter belt) location on my mother-in-law’s car (I don’t drive any more and don’t as a result own a car but I could, conceivably, use her car in an Uber-driver arrangement — and this sort of “pool car” working must be very common for Uber drivers). I have a squeaky clean, valid licence, no convections of any sort and live in a low-risk area. I stated my profession as taxi driver.

I was just refused cover (“couldn’t quote based on information provided”) for a commercial policy.

The underwriting rules must be now very tight and I would only get cover by going to a specialist insurer. You don’t get told the exact reason for an insurer refusing cover, but it must be because they can’t price to risk effectively. Or they simply don’t want to participate in that particular market.

If I can’t get “off the shelf” (i.e. standard policy terms) cover, there must be a lot of Uber drivers who will also struggle.

Uber does not require commercial insurance, just some “proof of insurance” I suppose, in order to not appear too much like an employer by stating that as a requirement. They leave this up to the individual driver/independent contractor to decide as to whether or not they want to be ethical (I pay $110 per month more for my commercial coverage). Supposedly, Uber will cover anyone while they have a passenger is in the vehicle and on a ride. Just last night, an Uber driver in my city lost her in an accident and being passengerless, it’s all on her insurance. If she didn’t have commercial, they will probably deny coverage.

In London all minicabs (uber) are required to have hire and reward insurance. These policies are expensive and as uber drivers are already earning below minimum wage many of them can’t afford this insurance.

I’ve wondered about the insurance situation for Uber drivers (I was in the insurance biz 30+ years) so I finally got around to looking into it.

It appears that Uber provides $1 million liability coverage when the driver is using a vehicle for ride “sharing”. From their website: https://www.uber.com/drive/insurance/

This is important because the standard Personal Auto Policy (PAP) used in the US specifically excludes coverage when a vehicle is being used for commercial purposes (i.e. driver/vehicle for hire). It should be noted that the exclusion not only applies to passenger services but also to delivery services such as pizza delivery.

The potential Uber driver should be aware that that Uber provides only liability; no coverage is provided for damage to the driver’s vehicle. So, if a driver’s car is damaged while engaged as a taxi, repair costs come entirely out of the driver’s pocket. Or the driver could try to get the damage covered under their PAP by lying to the ins. co. about what they were using the car for at the time – this means committing fraud.

Also every personal auto insurer I’ve written for will not issue a PAP on any vehicle used for commercial purposes if it is known upfront; and if it is discovered after the policy is issued, the ins. co. will cancel or non-renew coverage as quickly as legally allowed.

Externalities indeed

Hubert hammers the bases. Fake business news from a phalanx of business news reporters and at least one of them provides evidence he doesn’t understand the difference between a profit and loss statement and balance sheet.

One of the two reporters that published the leaked data (Efrati) argued that “Uber’s departure from China in the middle of the quarter helped slow the growth rate of its losses” and that the losses “reflects its increased investment in areas like self-driving car technology and mapping.” Neither of those claims is credible. Both impacts of the sale of Uber’s shareholding in the failed Uber China venture (which include a multi-billion dollar gain from Uber’s new shareholding in Didi Chuxing) and investments in speculative future ventures like driverless cars would impact cash flow and balance sheet statements, but not 2012-16 quarterly operating P&L statements, and it is not clear that the reporter understands the difference.

Then there is economics professor Levitt, Uber turd polisher extraordinaire, exposed as worse than the fake business news reporters, as it was his piece of work that sucked in the fake news reporters.

Have pity on his students and treat them with kindness, as they have been lobotomized.

The professor’s math goes like this. Uber has imagined into existence almost 1.5 Nimitz units while in the real world the equivalent of sinking at least two and melting one down to the waterline.

Why would anyone be surprised that a discipline which so worships ‘free’ markets would sell itself to the highest bidder? For U. of Chicago economists, this is the height of logical consistency and moral/intellectual integrity. That the NYT, WSJ or Bloomberg would uncritically republish this Fake News is similarly completely in character.

While I believe that Uber is losing money hand over fist the service has been great whenever I have used it or anyone I know has used it.

In my opinion it has been far superior to the old cab service which I still use from time to time.

A lot of that is the cab service & their regulators fault. They should have followed up with their own app with the same features that worked across states. I know that some cab companies have now bought something online but everyone seems to have their own app.

‘In my opinion it has been far superior to the old cab service which I still use from time to time.’

ding, ding.

Uber is awful. Incumbent taxi service is awful as well, just a different flavor.

100% regulatory capture. Something the Left doesn’t think about when advocating government solutions to social problems. Ironically, Uber benefits from regulatory capture too, using its army of lobbyists to infect local City Halls.

My stint as an Uber driver has soured me from being a Progressive/Liberal government interventionist.

PS, the free market right stinks too—-again just a different flavor.

I have it on good account that 17 national intelligence agencies have examined the data and are in total agreement that Uber is a highly profitable company. Anyone questioning these results might want to consider other long-term living arrangements. Certification of questionable data is now available to companies and individuals for a fee and includes enforcement opportunities to make one’s critics disappear.

Hey give him credit, Levitt finally got something right:

>Levitt claims “Uber embodies what economists believe should happen with the labor market,”

Likewise, four out of five doctors surveyed believe Lucky Strike has the smoothest taste…

Something is wrong in “Denmark” when a company like Uber has to churn new workers/slaves by offering them a $1,000 bonus (paid for by the VCs) for signing on with the company, while lying that the drivers can make up to a thousand a week, all the while driving an assent (their car) into the ground for the reality of less than minimum wage. How would any employment model consider that good business? They care not a bit about the humans being used in this equation, they look forward to a very buggy riderless model that will likely go to cr@p once it’s full-scale. It’s astonishing.

What the media excels at is ignoring the human costs of this operation and the fact that Uber rarely fulfills this bonus promise.

In conversation at a New Years Day party, several supposedly knowledgable Wall Streeters were all singing the praises of Uber as a highly successful economic model. Having read this entire series it is clear they know exactly nothing about Uber — other than there is a lot of positive smoke, there was Amazon, therefore Uber is the next great success.

They also believe, despite what their eyes tell them, that Uber ride-sharing helps with Manhattan traffic during rush hour. And these people manage hedge funds. Heaven help us.

Philip Mirowski’s co-author, Edward Nik-Khah talked about Steven Levitt here in the context of economics imperialism by neoliberals. – https://www.google.co.in/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=video&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwiDy_m-7qPRAhUGsY8KHUdxBJQQtwIIGjAA&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DNmnJGflu5bM&usg=AFQjCNF_aCKv5omJlShdI1NhBrc7qTr6sQ&bvm=bv.142059868,d.c2I

Anyone who has taken a London taxi in rush hour understands the appeal of Uber (or of the minicab alternatives which are pricier but still cheaper than the black cab alternative). For short journeys where there is no congestion, or if you are going to a mainline train station (where only London taxis have access to close-in dropping off points), a London taxi can’t be beat. Given the proliferation of cycle routes, congestion is now an ever-present reality on most central London routes. Aside from that, “proper” cabs are so costly that it has become a luxury choice. The costing structure needs revision if London cabs are to remain competitive.

As to the SatNav issue, not all Uber drivers are clueless — and not all London cabbies are as ready to take “the backs” (short, cheaper short cuts) as you’d like to imagine…

Not that you would care, but your typical trusty Uber driver receives around $2.50 to $3 for your minimum fare and that doesn’t take into account their costs (increased insurance, gas, wear and tear) and that they are lucky if they get 2 of those rides in an hour.

If you can live with that knowledge and NOT tip your driver, then God help you when the tables are eventually turned on you.

Having driven Taxi for sixteen years, 77-93, I believe I can verify that the Uber numbers don’t add up, and that as Yves says;

When I left the business the charge per mile was close to what it is now, $2.50/mile.

The lease payment amounted to about $60/shift, and Gas another $40-$50.

If a driver managed to take in $200-250 in 12 hours, he/she would walk with about $90-140.

The element of chance in the Taxi industry is such that it requires long hours, but it was a flexible profession that once allowed one to keep body and soul together, with a lot of hard work.

It is easy to see that at Uber’s $1/mile charges there isn’t much left over for the driver, but it takes a while for this reality to sink in, and drivers will put in a lot of effort, only to discover that they cannot make any sort of real money as a Uber driver.

In the mean-time Uber is damaging the legacy Taxi businesses as the article outlines.

It should be easy to understand for anyone not covering their eyes and sticking their fingers in their ears, that drivers splitting $1/mile with Uber are not left with enough earnings to justify their efforts, which unfortunately does not become clear until they’ve put in enough time to verify that reality.

I’m waiting to hear someone accurately observe that Uber is leveraging their drivers naivete to enlist their support in driving legacy Taxi and car services out of business so as to capture for investors, what they believe is a ‘surplus’, that being the difference between the $90-140 that a legacy driver can earn per shift, and what those Uber investors believe is the lowest pay they can offer that will keep their service working.

It’s easy to see where this is leading, the math, using the figures I explained above, is as follows;

take the $90-140 taxi drivers earn per shift, and subtract what a minimum-wage worker earns in twelve hours.

(Minnesota’s min wage is $7.75/hr. 12 x $7.75 = $93.00)

$90.00 – $93.00 = -$3.oo (Minnesota’s min wage is $7.75/hr.)

$150.00 – $93.00 = $57.00

User’s efforts are designed to capture that $57.00 ‘surplus’ for investors because individuals do not deserve to keep any more of the fruits of their labor than the ‘Market’ allows.

The intent is, in the end, after Uber drives legacy Taxi and car-services out of business, it will turn on a dime and demand the same fares that Taxis and car-services now charge, or higher (they intend to recoup the losses incurred in the battle to gain their monopoly) and what is left is not $billions in consumer value delivered by the invisible hand, but the usual carnage of forced austerity/misery.

Uber has even foreseen the problem they’re going to have getting drivers to work so hard for nothing, and is busy dreaming of driverless cars so they won’t have to deal with employees, I mean self-employed contractors.

(They intend to trade the difficulty of ’employees’ for the tax benefits of a large capital investment in driverless cars and the related depreciation)

Uber is the face of end-game capitalism, the unbridled destruction of the wealth we hold in common, in the interest of a few rapacious investors.

I feel rather certain that Uber will fail to conjure their complete vision into reality, but the history of the successes the investor class has achieved in harvesting any ‘surplus’ the labor class might have gained over time is plain to see.

They could well succeed in killing the current taxi/car-services, but they will probably fail in continuing to deliver a useful, affordable service to take their place.

My take away in short;

Uber has promised investors a share of profits derived from harvesting the ‘surplus’ currently enjoyed by Taxi and Car service drivers, as described above.

Their investors think this looks like a good plan because most of their other efforts to harvest ‘surpluses‘ previously owned by labor have paid off, and it fits their ideology.

Of course Uber’s owners don’t care if it works or not in the long-run because they will reap a large portion of the ‘surplus’ cash that the investor class has wagered on Uber’s success because otherwise it is sitting around doing nothing.

In the end, when you, or anyone have no ‘surplus’ to harvest, they quit robbing you directly, and instead, put you in jail where you are still worth something to your ‘host’, most likely a private, for-profit prison corporation and it’s investors.

A business model built on a an obvious screwing of the working class is the surest way to attract investor money.

One could be forgiven for thinking it’s the only game in town.

Thanks for presenting the driver’s economics in this understandable way.

“A business model built on a obvious screwing of the working class is the surest way to attract investor money”

And the basic game plan for business going forward. Since any real “growth” in this economy is of the massaged-numbers type, the only way to make money is screwing your customers, or your employees, or (usually) both.

One wonders how much Uber’s business model is based on some poor schlub (who can’t do math) buying a new car on a seven year, zero/low interest loan, then driving this vehicle into the ground, or until repossessed, whichever comes first.

And how much of this “negative equity” has been rolled into current new car sales. A Ponzi of a different flavor.

We Are The Ferengi

I was gaining entrance to a hedge fund office a month or so ago when a manager came in complaining to security of not being able to find his way into the building due to road construction outside. He “had” to pack behind the building, across the street. I had followed the detour signs to the garage and actually found a more direct way in, and abundant parking spaces, than previous visits.

I also get paid for “repairing” printers by removing toner packaging and similar lost arts :-)

this was meant to be a Reply to Mikerw above.

Hi Yves, thanks for the good work. Surely it’s perfectly consistent for Uber to be (a) valuable to consumers (for now) and (b) a terrible business model from a profit/investment perspective. Yes, its competitiveness depends on unsustainable subsidies, but that benefit (again, for now) is going to its users. As your series argues, the investment thesis may be that the unsustainable subsidies only need to last for as long as it takes to knock incumbent taxis and the like out of the market and create a monopoly for Uber. We shall see if that happens.

I too wish Levitt et al had made an effort to compare consumer surplus/welfare as they calculated for Uber with what existed without Uber – it’s not as if Uber created it all, taxis and other transportation provide it too. That doesn’t make their analysis completely invalid, however – just in serious need of context. I had a crack at providing some of that in the piece linked here, drilling down on New York City. Although comparisons require fairly heroic assumptions, the big picture numbers make it really hard to see how Uber can ever “throw a switch” to start making money: http://www.breakingviews.com/features/ubers-70-bln-value-accrues-mainly-to-customers/

Uber is a scam, up front.

The cost of having a reasonably responsible person, driving a safe and insured vehicle, transport you from one place to the other costs roughly $2.50 per mile in most of the country.

Many decades of Mr. Market’s invisible hand working diligently have proven this fact.

Promising to do the job for $1/mile is a fairytale, and I believe most poor people who currently rely on Taxis understand the economics better than their middle-class cousins.

The fact that once Uber can achieve a monopoly by destroying current Taxi and car-services, they will be free to charge what ever they wish is not lost on the poor.

Uber’s business plan relies on desperate/naive drivers on the one hand, and stupid investors on the other.

Benefits accrue to a very small number of ‘clever’ people in real-time, the benefit to riders is short-lived and designed to disappear, meanwhile the damage inflicted is immense, designed to be permanent, and impacting many hard working people.

Uber is a scam, and to believe otherwise is the same as believing in the tooth-fairy.

Well, I am not a user of Uber. But I think the question is not about whether there are benefits to users, rather:

1. Are the benefits as large as Uber has mentioned?

2. Should the benefits come in expense of everybody else e.g. drivers, and ultimately society?

Although I am not a user, the benefit of Uber just like many other app/tech economy companies is that is shows most people as being hypocritical. They complain about subsidies to others, but then if they got the so called subsidy, they think it’s ok.

Any company that performs these kinds of service should be supported.

As an Uber Outreach specialist, I can tell you first hand the driver attrition rate is horrendous, it’s around 3 months before they quit, and after they get their signup bonus. So usually half of Uber’s workforce quits every 3 months based on my data of driver recruitment.

The rider subsidies are the real-world value for a driver to make a living, and to maintain the car. Uber lowers the cost of rides, while taking higher and higher commissions; basically making that driver have to work an extra 2 hours more during each price cut to around 12 to 16 hours to break $150. Those drivers that can hit the quota actually get back the cost of time and maintenance of the car, but only around 12% of Uber/Lyft drivers can hit the mark.

The majority of times they don’t, so this claim that “Any company that performs these kinds of services should be supported.” is a joke. They put the burden of car ownership on the driver knowing that if Uber can create a large enough supply of drivers to replace those that burnout is unsustainable game, when there is no end in sight that taxi will just go away before all VC money dries up.

I am sick of knowing that drivers are not paid fairly, while consumers are just expecting services for pennies on the dollars. Silicon Valley needs to burst this Uber bubble and learn a valuable lesson that greed will always lead to a downfall at some point.

Thanks!

Thank you.

. . . the investment thesis may be that the unsustainable subsidies only need to last for as long as it takes to knock incumbent taxis and the like out of the market and create a monopoly for Uber.

There are anti dumping laws for physical goods, such as for example Chinese steel being dumped into the US which now draws a tariff. Dumping money to do the same thing draws kudos from economics professors and financial fake news journalists..

. . . the investment thesis may be that the unsustainable subsidies only need to last for as long as it takes to knock incumbent

taxis and the likesteel mills out of the market and create a monopoly forUberChinese steel mills.Exactly!

Thanks for the reminder.

I appreciate the analyses presented here. So fine, tear down Uber, maybe Uber collapses at some point, maybe they survive long enough to put taxis out of business and raise their fares with monopoly pricing.

But the simple fact is, here in DC, taxi service stinks and has never not stunk in my memory. The taxi I took home from National last night was just another reminder — where do they get these drivers? They don’t seem to be able to actually drive an automobile, but they’re proficient in clicking the added charges lever. This has always been true. Some of the scariest moments I’ve ever had in a car have been with taxi drivers at the wheel.

Getting rid of uber doesn’t solve the on-demand hired car transportation problem.

Why don’t you hire a limousine or rent from someone who will come get the car from your house?

Not only is the food terrible, the portions are so small.

The problem is that the pay is too low. How much expertise do you think $90-$140 per shift buys in DC?

Perhaps it is that low, which, being generally familiar with taxi fares here, I doubt. But if you’re arguing that attracting a better class of driver is why Uber has to subsidize their business, well, the X drivers aren’t happy even with that. I think it’s more likely that with the subsidized Uber we end up with an even lower class of driver in the taxis. But back to the real problem at hand — we’ve had six fantastic long-form studies that have destroyed the investor model for Uber. Ok. Now then, aside from generally awful taxi service, what is getting us to the airport? Unless there’s some drastic improvement to taxi service, it is going to be a private entity, likely Uber at this point. More likely long-term we’ll all be riding in Johnny Cabs to get rid of the labor factor for *someone* if not Uber, so I think the classification of self-driving cars as “bezzle” is rather unimaginative.

Obamacare doesn’t work very well. Killing it in favor of 100% privatized health care would not be an improvement.

Taxi services in major cities have some serious problems. Uber doesn’t address any of those problems, instead making them worse and adding more. Self-driving cars are a rent-extraction scheme to obtain fiat currency by promising public benefit, deliver none, yet keep all the dishonestly and dishonorably obtained fiat currency in inaccessible private accounts. That sounds pretty bezzly to me.

I had a couple of scary/ infuriating experiences with DC taxis. The first, years ago, from a large hotel where macho drivers of a certain ethnicity were favored by the bellmen, and tried to rip me off. Second, from Franconia Metro, where the driver, no seat belt, seat basically in a horizontal position (i.e. good for sleeping, but not driving), had to go on I-95 south for ten miles. With foot on gas but not ever checking mirrors, he almost doomed his taxi and both of us occupants.

However: with a taxi, there is an agency I can complain to (was glad to arrive alive in the second instance and did not bother). I am not keen on being driven around by Uber drivers who have little experience, and have not and would not use Uber, period.

I also have lots of positive experiences with DC cabs, including several times hiring them for hourly rates to drive clients around for a DC night tour.

Quite a Catch-22 for Uber. The only way they provide benefits for consumers is through investor subsidies, but the only way they can satisfy their investors is by eventually getting rid of those subsidies, which they can only do if they successfully drive out their competition and establish monopoly power. So I’m pro-Uber if all they are is a way for investors to throw away their money subsidizing car trips, but anti-Uber if their “destroy all competition” business model has a chance of actually working.

People carry on about pricing wrt Taxis yet completely forget wages have been stagnant or worse since the 70s, yet cheer on Wal-Marts et al cheap prices….

disheveled…. like gravitational waves compressing the weaker on the way down… until ultimately they suffer the same fate…. environmental information event horizon seems to negate discovery until its too late thingy… oh wellie….

Can we use these numbers to turn the argument Leavitt presents on its head and argue thus: if $6.8B is the consumer surplus being provided, and $2B* is the subsidy that the Uber investors are providing to riders (as this series has successfully argued earlier) then there is a sweet spot where uber should raise ride prices immediately to reduce the “surplus” to say $2.8B, thus realizing an immediate profit of $2B for its investors?

The math : current surplus 6.8B – final surplus 2.8B = 4B extra revenue. So, if uber is in the hole to the tune of 2B due to subsidy, then final profit will be $2B.

If uber really believes in this demand curve estimate, then customers should continue to flock to its service because they still get a “surplus” of $2.8B under this scheme. So, should not every uber investor demand that price increases be implemented today to realize this profit? Why should they be taking losses unnecessarily?

* as i recall, the annual loss is $2B. Adjust math to actual loss figure.

They’re not taking losses unnecessarily, they’re taking losses to drive the competition out, at which point, as you point out, their need to raise prices will be unimpeded by competition. one thing left out of uber defenses, also, is the need for riders to have a “smart” phone, and they’re not free, so add that into your calculations. You don’t need an i phone for the bus or bart or the subway or the light rail or any of those things. Of course another angle of the uber enterprise is to get rid of those things in favor of a gov’t subsidy to uber which I’m sure they want. The problem with this is poor people can’t do surge pricing. I can take the bus from one side of seattle to the other for $2.75 peak hours, I can travel from king st station to anacortes ferry for roughly 8 dollars. That’s the sensible future of transportation, not a fancy scheme to fleece investors and cabbies for the benefit of a few tech titans, followed by the bait and switch later when they’ve got you over a barrel (actually they already, as pointed out in the article, do that because you find out it’s surge price after you’ve got the car there, so you’re more likely to accept the gouge). Further, as if it needs to be pointed out again, the drivers are depreciating their asset, paying insurance and buying gas at less than accepted rates, why should they do that for the tech titans (as the investors are obviously not making money)?

That $4 billion is the drivers 75% commission cut that is gobbled up. Their model is non-sustainable because Uber has foolishly used VC money to try to price out competition, while having to flood the market with new driver through bonuses and subsidies to keep a top-line of revenue, which seems to never come to a break even point.

The hole they have dug themselves will soon implode unless they increase driver pay, which means take away rider subsidies,which they can’t. So Uber basically shot themselves in the foot by the ideology of pure greed. They can’t raise prices anymore, and if they lower prices they will have a massive driver fallout, so all in all we are just waiitng for Uber to fold. I give it 4 to 5 years.

This entire series has been an exercise in futility. It began from the premise that Uber cannot be “welfare enhancing” unless it met four arbitrary and illogical tests that the author selected, including that it must “provide service at significantly lower cost, or the ability to provide much higher quality service at similar costs.”

Says who? If Uber provides even marginally lower costs, or even marginally better services, then it will by definition be “welfare enhancing.”

Further, the series has had a schizophrenic inability to choose a perspective for the analysis. Is it from the perspective of an investor? Because, personally, I couldn’t care less whether Uber’s investors realize a return.

Is it from the perspective of the consumer? Because, if so, it is clear that the author has never lived in a city without owning a car. Uber has overtaken the industry not because of investor subsidies, but because it has been replacing a grotesque industry long-ruined by regulatory capture. Taxi service in DC has been miserable for decades. It has always gotten worse, never better, as even the switch from “zone” pricing to mileage pricing failed to improve things. Using a credit card was pure fantasy. Getting a cab anywhere outside of the city center an exercise in futility.

The simple fact is that Uber is light-years better than taxis. As an example, how did the author value the ability to recover a lost phone? I lost more than a couple in DC cabs (never to be seen again), and have had more than a couple returned by Uber drivers.

Mr. Horan has an impressive resume for analyzing air carrier M&A, but it is notable that no industry in the world is more heavily regulated and subsidized, with cabotage prohibitions forcing customers to subsidize every airline that has ever employed him. Likewise, Mr. Horan appears to believe that it’s fine for the government to force customers to subsidize taxi service by drastically limiting competition, but is beside himself that investors do so willingly for Uber.

I hate to be mean but you asked for it.

Lordie. Your comments indicates a reading comprehension problem.

Despite the fact that Uber does not have barriers to entry (other people can write apps, other people can set up local transportation services), it is acting as if it is operating in a market that can be monopolized and is engaging in predatory pricing to drive out incumbents. That is what this series has shown. Uber is a high cost producer, and the only reason you perceive that you are getting a better deal is due to massive investor subsidies.

Because those subsidies cannot be sustained (indeed, as Hubert has repeatedly pointed out, Uber needs a massive change in its margins merely to break even, let alone to achieve an adequate return), Uber will sooner or later start giving everyone a much worse deal than it is giving now. And it will be worse than traditional taxi services because 1. Uber is inherently a high cost producer and 2. Uber’s investors have higher return targets than taxi industry incumbents generally do.

The reason that the investor perspective matters is the company is being run, at least in theory, to benefit them, not you.

I think the investors are getting smoked too, and if they fail to understand that, it will be their total loss eventually. They do have a problem in that once the first few want to bail out, like a spooked herd, the rest will want out too.

Or they can’t bail and have to ride it out no matter where it takes them. Maybe Kalanick has them handcuffed to each other around a tall pole that they can’t get over?

Thanks for this series about Uber. Hubert’s analysis is eye opening and a teaching event for this peasant.

I’m curious to discover how stupid the investors really are. My suspicion is very. The Theranos debacle suggests that venture capital (does that term still have meaning?) has gotten very, very stupid and lazy, perhaps in part because 2008 showed them they never have to fear making a mistake; they will always be made whole, and they’re now swimming in so much money they literally CAN’T fall out of the 1%.

What happened to the investors in Chelsea Clinton’s husband’s hedge fund? The one that lost 90% and then shut down. Did he even see a reduction in his cocktail party invitations?

That was the nicest meanness I’ve ever encountered.

Every industry has barriers to entry. Even a house painter needs the capital to buy their initial equipment. As for transportation and Uber in particular, a new entrant needs substantial capital to obtain even a scintilla of market share. People can “write apps,” but then they just have an app. It takes a lot more than that to obtain customers.

If Uber is “acting as if it is operating in a market that can be monopolized and is engaging in predatory pricing,” then we should all be rejoicing. In fact, your own statement is the reason that we should not be at all concerned, as predatory pricing only presents a risk in markets that have high barriers to entry.

There is a reason that predatory pricing claims are a thing of the past. Antitrust laws exist to protect competition and consumers, not to protect competitors. If Uber wants to engage in predatory or below-cost pricing, then they are conferring an indisputable benefit on consumers; lower prices benefit consumers.

Further, the law actually recognizes the “bird in the hand” value in this instance. Specifically, for the lower pricing to be actionable as “predatory pricing,” the cost savings must be more than offset by future price increases, taking into account: (1) inflation; and (2) the time-value of money. In a market with low barriers to entry, it is effectively impossible to make that showing.

I don’t “perceive” that I am getting a better deal. I am getting a better deal. The fact that investors are subsidizing that deal is of no consequence from the consumer’s perspective (or from the law’s perspective).

Further, the assumption that those subsidies cannot be sustained is just that: an assumption. There is no indication that investor’s appetites for Uber are abating. And how long was Amazon subsidized by investors before it made a profit (if it even has)? Are Amazon’s early investors complaining today?

You claim that “Uber will sooner or later start giving everyone a worse deal that it is giving now.” I have already been receiving exponentially better service from Uber for four years. Four years. In the (unlikely) event that Uber’s investors balk and it is forced to raise prices, do you believe that it will take more than four years for the market to adjust? There is a gaping hole in your theory at this point, as your first paragraph claims that there are “no barriers to entry”, but then your second paragraph claims that consumers will be hurt because the market will be unable to adjust when Uber raises prices. Those are diametrically opposing statements. If there are, in fact, no barriers to entry, then any price increase by Uber will prompt would-be competitors to enter or re-enter the market.

If you want to critique Uber from the investor perspective, then that’s fine – have at it. You can make a case that it’s a bad investment.

The problem is the conflation of that perspective with a protectionist desire to shield legacy providers (i.e., taxis) who provided an inferior product at higher prices, and disingenuously using the interests of consumers to prop up your inherently unstable argument.

Uber customers prefer Uber to taxicabs. If taxis want to win back market share, they are free to attempt to do so. If they want to start up a competing service, they are free to do that as well. Since — according to your assertion — there are no barriers to entry in this industry, they will be able to do so the minute that Uber begins raising prices.

The only people who seem to be complaining about Uber are taxi drivers, and people who want to protect taxi drivers from lawful competition. Fortunately, the law protects us consumers from such ill-advised inclinations.

They hope to become a monopoly and force rates back to the old taxi rates and then cut off drivers for self-driving cars; so the consumer loses those cheap rates again, and tens of thousands of drivers were exploited in the short-term for a mere handful of billionaires, so yeah right now you can rejoice, but every ride you take now is coming out of the pocket of the driver (I don’t have sympathy for the taxi industry) . So in the end your acting like narrow sighted person with no moral compass of any corporate social responsibility .