By Georg Zachmann, a Senior Fellow at Bruegel and a member of the German Advisory Group in Ukraine and the German Economic Team in Belarus and Moldova. Prior to that he worked at the German Ministry of Finance and the German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin. Originally published at Bruegel

Brexit promises pain for Ireland that could be cut off from the EU internal market and be left exposed to market instability in the UK. Georg Zachmann assesses the scale of the possible damage for Ireland, and how the UK and EU might use the special energy relations on the Irish island to commit to a pragmatic solution.

Ireland is the EU member state that will be most impacted by Brexit. A particular case in point is the energy sector. Currently the Irish electricity and gas markets’ only physical connections are with the UK. So, after Brexit, these Irish markets would not be connected with the EU anymore. This has material implications.

Adverse Effects for Irish Gas Customers

Currently, Ireland imports about half of its gas consumption through the UK (the rest is produced domestically). While there is no reason to believe that these gas flows will be stopped after Brexit, there might be three possible adverse effects for Irish gas customers:

- The liquidity of the UK gas wholesale market (NBP) might suffer from falling under different regulations compared to its EU counterparts. This might translate into more volatile and somewhat higher prices. As Irish gas prices will remain tied to the UK gas market, this would also affect Irish consumers.

- The risks for Irish consumers would increase, as EU solidarity rules – which imply that the UK would have to prioritise Irish household gas consumption over UK industrial consumption in a supply crisis situation – would cease to apply (but the 1993 protocol between the network operators on dealing with gas emergencies on either island would remain untouched by Brexit).

- The likely most important implication of Brexit is that Ireland will be unable to continue to participate in the development of the common gas market once it is no longer connected to the EU. Being outside of this large, liquid and competitive market will not only imply higher and more volatile gas prices, but it will also affect the investment decisions of gas companies in Ireland (as access to the large EU market is an anchor of regulatory stability).

Adverse Effects for the Irish Electricity Sector

The same considerations apply for the electricity sector as for the gas sector. While the trading volume in electricity is smaller (as electricity is largely generated and consumed domestically), the long term implications for this sector are likely even bigger than for gas. Electricity markets are complex markets based on thousands of pages of rules on the obligations of individual players and the specifications of the traded products. The EU is rolling out a market design to all its member states to ensure the joint optimisation of the EU electricity system. That is, if the wind is blowing stronger in Portugal, a gas-fired power plant in the Netherlands might be signalled to reduce its production. If the UK is unable to stay in the internal market, Ireland would also be decoupled from it. Given the increasing role of renewables in the EU as a whole, and the unique wind patterns on the Irish West coast in particular, situations in which Ireland might want to export or import large volumes of cheap electricity on short notice will become more frequent. Consequently a decoupling of Ireland from the internal electricity market could imply a greater need to invest in the back-up capacity in Ireland, lower revenues for wind power exports, and hence more volatile and higher electricity prices for consumers.

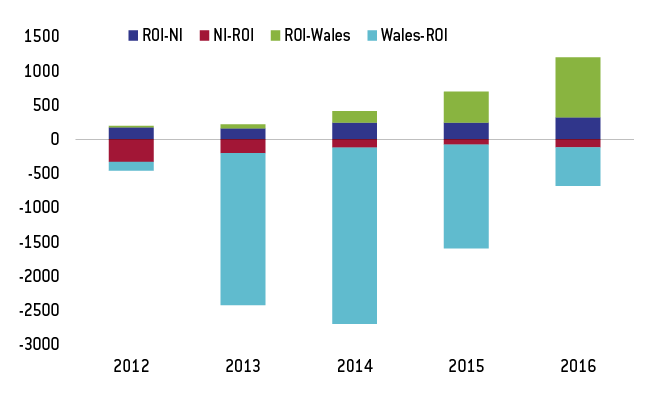

Source: Bruegel based on UK Government (2017).

The Special Case of Northern Ireland

However, the reliance of the Republic of Ireland on the UK is only one side of the story. On the other hand, Northern Ireland may also be significantly affected by Brexit. Northern Ireland imports electricity and gas from the Republic of Ireland and this dependency is set to increase as several power plants in Northern Ireland are expected to close. Furthermore, both parts of the Irish island share a Single Electricity Market (SEM), which is supposed to be further integrated with the EU internal electricity market. If Northern Ireland would have to leave this joint Irish electricity market, it would be too small to sustain a functioning electricity marketwith multiple competing suppliers and different types of plants for different demand situations. Hence, Northern Ireland is at risk of losing the benefits of a competitive electricity market and at the same time requires expensive extra capacity to ensure secure supplies.

Conclusion

Current discussions suggest that the UK will leave the internal energy market because of matters of principle on both sides: On the one hand the EU does not want to accept a special treatment of trade in specific sectors (“no cherry-picking”), while on the other hand the UK does not want to be bound by EU institutions that are crucial for the functioning of this market. The complex case of the Republic of Ireland might offer the UK and the EU27 an opportunity to still achieve this first-best solution. The EU might argue that accepting full internal energy market membership of the UK is the price to pay for allowing the Republic of Ireland to fully benefit from the EU internal energy market. At the same time the UK might find the loss of sovereignty that comes with accepting the EU internal energy market rules acceptable in order to ensure competitive energy supplies in Northern Ireland. The rest of the UK would also certainly benefit from being in the internal energy market. This mutual dependency between the UK, the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland can be a credibility device for both sides, which might help convince investors of the stability of the arrangement by which the UK stays inside the EU internal energy market.

If one needed a single valid reason for exiting the EU, then the astoundingly cack-handed interventions from EU directives on energy supply and transmission is probably a good candidate. Unfortunately there’s no EU cherry picking allowed so it’s not that simple because stomping off in a huff about the bad bits means you lose the good bits too, but that’s another story entirely and is being comprehensively covered by Naked Capitalism elsewhere so I won’t digress on that subject here.

Now, in fairness to the EU, they are simply doing what they have always said they are all about doing, which is to attempt to instill some kind of consistency and harmonisation on member states’ individual internal domestic markets. But because of over a century of history behind the development of generating assets, distribution grids and end user supply and sales in each country, this always was, in my view, a Fool’s Errand. It was never really going to work because any attempt at EU direction setting would end up in contradiction with and overlapping the various national frameworks for regulating what is — always and everywhere — a natural monopoly.

This is precisely what has happened. To the can of worms that is a regulated utility, the EU has attempted to add — how best to describe it? “populist neoliberalism” maybe? — free market, anti-monopoly and competition policy making.

It has resulted in an unmitigated mess which now no national government can clean up on its own and no-one seems willing or able to rein in the Commission and try to roll back some of the more ridiculous stipulations (most notable the separation of generation from distribution from wholesaling from retailing). It is hideous and makes the ACA look a model of well organised sanity by comparison. This is a good overview of the U.K. situation. Even that does gloss over some details like the mandatory provision that you have to offer any source of electricity generation a connection and you have to offer any load a supply; you can charge for these connections but that accounting and market-making condition has zero engineering foundation in terms of how you want to design and manage an electric supply and distribution system. (note the emphasis — in terms of the science it needs to be managed as a system, not some god-awful rag bag of mismatched and unplanned individual parts).

Returning to the topic at hand (this really is too big a subject to cover in a comment so apologies for the inevitable omissions due to oversimplification) and again being fair to the EU, it has demonstrated commendable pragmatism in the actual implementation of its directives. People who aren’t overly fond of the EU such as I might well say “huh, that’s the least they could do to try to clear up the mess of their own making”, but that’s maybe a tad harsh. There have been a significant number of waivers granted, of which the East-West (UK to the Republic) interconnecter is most relevant for this discussion.

Short version: when the need arises — or when leaned on by sufficiently powerful vested interests — the EU is no stranger to waivering its way out of a tight spot. I suspect it will have to do so to get round the issues ably explained in the above post. Either that, or they’ll dig their heels in, just because they can. Time, as usual, will tell.

In both the post and your conclusion, I see some dangerous assumptions that the negotiations are based on reason – on either side.

I suppose that if the worst happens that more eyes might swivel in the direction of the Corrib oil field off Ireland’s west coast, which has been the cause of much controversy, not least because it appears that the Irish government including the convicted Ray Burke & the aptly named Teflon Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, sold it off for peanuts.

http://www.shelltosea.com/content/just-how-bad-irelands-oil-gas-deal

Shell lost a vast amount of money on that scheme, which was always ill-conceived. You are right of course that there was always something incredibly dodgy about that scheme – to its eternal shame, the Irish Labour Party defended it when in power and even tried to extend the ‘incentives’. One of many reason why they will never, ever get my vote again.

Yes, like the Green Party they burned many bridges as they walked into the Dail.

For those with an interest, this website gives an excellent ‘live’ picture of electricity use and the use of interconnections on the island of Ireland (you can compare power and use rates in Northern Ireland and the Republic by clicking each individual graph and adjusting accordingly). The Republic of Ireland has always, incidentally, been a world leader in energy storage technology precisely because the small size of the island has meant that the grid is too small to be efficient. Unfortunately, neolib ideology meant that the main Irish power engineering company was cut down to size and prevented from operating internationally by the government in the1990’s as it was State owned (a long story, and not particularly relevant to this post).

Despite the supposed intention to connect Europes grid network, there was a proposal a couple of years ago to construct a number of gigantic wind farms in Ireland to export power direct to Britain, without interconnecting to the Irish grid. The idea was that they would take advantage of more generous UK incentives for offshore wind energy by becoming ‘British’ power generators. The project was officially cancelled about two years ago, but so far as I am aware the companies involved are still working on it in the hope of a change in UK policy. Its not impossible that Brexit could make this project more, not less likely, as Britain is likely to have a major shortfall in power over the next few years.

To an extent I think the damage caused by Brexit to the electricity market would be relatively minor in the short term, simply because the north and south systems are not particularly well integrated. There are active plans for a major interconnected, but work hasn’t started yet. It is primarily needed because of wind power. To compensate for a lack of interconnection, both halves would have to invest more in electricity storage, and probably gas generation as load relief.

Maybe you might know…Do you think Varadkar and Marcon’s announcement of €1 billion undersea electrical interconnector between Ireland and France was just hot air? I kind of thought so myself. However, if Ireland can generate some serious wind (and tidal?) surplus electricity, wouldn’t the traffic occur both ways and eventually connect us to the wider European market?

That scheme is not hot air – there has been quite a bit of work put into it for a few years now. But its a low priority scheme at the moment, but likely I think now to get a higher priority. No doubt its on the shopping list Ireland is giving Europe now as compensation for Brexit (especially as Ireland lost out on both major agencies it was going for).

The interconnected would work both ways, but in general Ireland produces a net surplus of power – this is always essential in a small grid to prevent brown- outs – one reason why electricity has always been expensive. France will soon have to start closing its coastal nukes and there is no replacement for them (the new reactor design is a disaster), so they will want the power, especially in the summer.

Thanks very much for the info. For such an important topic (energy), I’m such a dunce.

Its a pretty esotheric topic! I’m surprised sometimes that people I know who work in the energy industry have only a very poor understanding about how and why electricity networks actually function, and it doesn’t help when economists stick their oar in and complicate things unnecessarily.

I am in no position to evaluate the reasonableness of this scheme, but there are some precedents. The island of Gotland, about 56 miles from Sweden, with a population of ~60,000, gets its power via an underseas electrical cable from the mainland.

I just looked up the distance: 1532 Kilometers, Ireland to Brittany (which would have its own wind energy).

Seems like a long way to run a power cable, but PK would know better than I.

The official website for the Celtic Interconnector is here.

Although its significantly longer than most existing DC lines, I believe the biggest issue is whether the geology is suitable- the shelf there is quite complex and geologically active (lots of submarine glacial deposits which have a habit of shifting). They’ve been doing geotechnical work along the potential route for a couple of years so far as I know.

My first thought on seeing the site was: what the hell is RTE (radio teilifis Eireann) doing in the energy business? Then it quickly dawned on me that it was a French concern with the same acronym. Synchronicity? Whatever, it seems I need to become a bit more Francophile. But, then again, most of the people I know living on mainland Europe tend to settle in Deutschland followed by Bruxelles. In fact, my niece is jetting off for an interview in Bruxelles in the new year. Cheap digs if she gets the job.

From the website: “The route is approximately 600 km long, of which the subsea element comprises approximately 500 km.” – 300 miles. A lot more than 52.

So my number above was wrong – about 3-fold.

All right, this baffles me. I thought that large grids were less efficient because transmission losses increase with distance.

When you say a “small grid”, are you really meaning “a grid having limited transmission capacity”?

You need large gensets to be efficient (600MW typically). The smaller your generating plant, the less efficient it is.

But in a grid with small-ish loads, you don’t need that many of those sorts of large generating assets to satisfy demand. So if you have relatively fewer, larger generator installations you have vulnerabilities because an outage of just one generating site at times of peak load has a proportionality very significant impact.

To counter this, you need a fair bit of spinning reserve. This, too, though is inefficient in both thermal and capital terms.

The larger the grid, then, in terms of generating capacity and demand, the more efficient it is, right? Ah, not so fast. Bigger grids mean longer lines and that means higher transmission losses (which was the point you rightly made). So above a certain size, large grids start to lose their efficiency wins.

Even that, though, is an awful oversimplification because you also have to factor in load densities and load profiles. Load density is better if it is higher — it is more efficient to supply, say, 2GW demand presented by a city than 2GW demand presented by highly distributed small towns. And if you have disconnect-able loads, like, say, an aluminium smelting plant, that is much more flexible than, conversely, a data centre.

Bet you’re glad you asked now aren’t you?!

I’ll finish by saying that all is is complicated enough from an engineering perspective. Slap on a stupid, stupid, stupid “market / pricing signals” layer and you have one ghastly mess to manage.

I’d just note that there are a number of significant projects in the ‘pipeline’ so to speak that will likely be affected:

1. There is an LNG terminal proposed in the Republic that has been on hold for about 10 years now. I suspect that there will be renewed interest in it now, along with gas storage (in Ireland, this is mostly in either exhausted offshore fields or proposed in off-shore saline caverns). This will significantly increase costs of natural gas in Ireland.

2. There are several active proposals for electricity interconnections with NI and Britain. I think these are likely to go on hold until the legal situation is cleared up.

3. There is ongoing geotechnical work to look at the feasibility of a direct interconnector between Ireland and France. I suspect this will become a priority scheme.

4. Ireland is already a world leader in electricity storage technology. There will need to be a ramping up fast in storage facilities as Ireland is increasingly dependent on wind energy.

5. There are about 1.5 GW of solar schemes permitted and ready to go pending subsidies in Ireland. Solar is an excellent counter balance to wind (i.e. it tends to be sunny in Ireland when there is a high pressure zone sitting over the country, which is when wind energy is down). Contrary to cliche, Ireland is actually quite promising for solar as we get lots of sunshine, it just always so damned cold at the same time nobody notices.

6. There may be renewed interest in wind power schemes in Ireland that connect directly to the UK – i.e. do not interconnect with the Irish or Northern Irish grid.

I have a technical question:

When did the Republic join the EU? Was it before, or after the UK?

Because a glance at the map, or for that matter close study, implies that Irish membership depends a great deal on British membership. Otherwise, they’re physically isolated from the Continent. The energy connections would be only one example. I’d wager most communications go via Britain, too.

Of course, most trade with Ireland goes by sea or air, anyway, so the extra distance isn’t a deciding factor, but it sure is inconvenient.

How far is it from the tip of Brittany to Ireland?

1,532 Km. Pretty far – Cornwall is in the way. There are ferries, though.

Same year as the U.K. — 1973. That’s when they let all the riff-raff in. I think they should have employed the impresario who used to own Studio 54 with his ability to maintain a notoriously stringent (and somewhat arbitrary) door policy (“you can come in, but your wife can’t”).

A lot of Eire’s economic development has been on services, so doesn’t rely on physical movements of goods. That said, there’s still a lot of agricultural exports and a fair chunk of these run via the U.K.

Hence the hoo-haa about the importance of resolving the north-south border.

Developments on the Trade front.

The newest roro ferry was supposed to operate between Dublin and Holyhead has now been commissioned to operate between Dublin and Zeebrugge.

“Operator, CLdN ro-ro SA (Cobelfret Ferries) welcomed MV Celine from a South Korean shipyard to the Dutch port from where freight traffic will use the newbuild’s 8000 lane meter capacity. In addition the 234m long by 38m beam ship will be the biggest ever ro-ro vessel to use Dublin Port that will also operate from the Belgium port of Zeebrugge…

According to the Dublin Port Company, Celine can carry over 600 freight units and is approaching twice the size of the largest ferry currently operating of the port…

Also announced yesterday by Dublin Port, record volumes which are 30% up in five years. The port company also highlighted the newbuild Celine, notably given this newbuild will boost capacity due to demand on direct continental services and as Afloat previously alluded the context of a post-Brexit Europe.

The environment of Brexit is creating uncertainty commented Eamonn O’Reilly, Chief Executive, Dublin Port Company who added that the port is to see more new services to continental Europe during 2018…”

Actually about 500k

The Subsea Interconnector part says that too (check their website)

Dublin to Marseille direct is about the distance you suggest

Yes, I saw that in the website. Must have misread my source. Thanks for the correction.