By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan has no financial links with any urban car service industry competitors, investors or regulators, or any firms that work on behalf of industry participants

Uber released new financial data this week, showing full year 2017 GAAP operating losses of $4.5 billion, and an operating margin of negative 61%.

Uber’s challenge is to get the business press to downplay or ignore its dismal financial results, and to present a narrative where these results demonstrate that Uber is making major progress. Although Uber has complete financial information, it only released detailed data for three quarters in 2017 and two quarters in 2016. Although much of the missing data can be filled in from earlier releases, Uber knew that reporters on deadline would not do that, and thus key changes over time would not be examined.

Uber’s financial releases have never used consistent definitions of “losses,” often using EBIDTAR or EBIT contributions instead of true GAAP Operating or Net Income. Stories about 2017 results would normally highlight comparisons with 2016, but because Uber has never supplied reporters with 2016 GAAP profit numbers, their stories did not mention that aggregate losses had continued to increase.

Every news report focused on the continued growth in top-line revenue. Most emphasized the major progress new Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi had made towards his goal of a 2019 IPO.

Only one news report, by Eric Newcomer of Bloomberg, highlighted the magnitude of total GAAP losses. Newcomer noted that “[t]here are few historical precedents for the scale of its loss” and explained “Uber prefers to use a different number to refer to its loss: $2.2 billion.” Newcomer recognizes that $4.5 billion GAAP loss was the better indicator of Uber’s current economic performance, but couldn’t explain its superiority to his readers because Uber refused to identify the costs excluded from its preferred number.[1]

The stories that highlighted Uber’s preferred narrative had difficulty linking those claims to the financial numbers that had been released. Emir Efrati led off his story in The Information by saying “Uber is moving toward profitability” even though losses were actually increasing and then emphasized that “[t]he results suggest Uber is getting more efficient as it scales up, allowing it to improve profit margins”[2] without any attempt to document evidence of meaningful scale economies.

The New York Times emphasized that the new numbers “reflect a steady improvement in the company’s financial position, with revenues growing and losses narrowing” but never mentioned the $4.5 billion annual loss (except to say that losses were “big”.)[3] The Financial Times highlighted that “Improvements boost new chief Dara Khosrowshahi as he prepares to take company public” Its lead paragraph reported the smaller EBIDTAR contribution numbers as “losses;” did not mention actual GAAP losses until the end of the story, and made no attempt to explain why it had emphasized the smaller contribution numbers, or why Uber was emphasizing a “profit” measure that excluded $2.3 billion in costs.[4] None of the stories identified the actual magnitude of recent cost savings, or explained them in terms of the overall achievements that would be needed to reach breakeven.

Did Uber’s 4th Quarter cost cuts reflect improved efficiency, or major progress towards profitability?

Uber did cut its costs in the 4th quarter, but a quick review of the reported data raises serious questions about the “Khosrowshahi making major progress towards profitability” narrative. As discussed at length previously, the issue is not whether a startup company might initially incur big losses, but whether its business model demonstrates the powerful scale or network economies that would steadily improve operating margins.[5] The issue is not whether Uber has, and will continue to be able to show in its IPO documents how it can not only reverse $4.5 billion in losses and achieve breakeven, but steadily grow profits for many years to come.

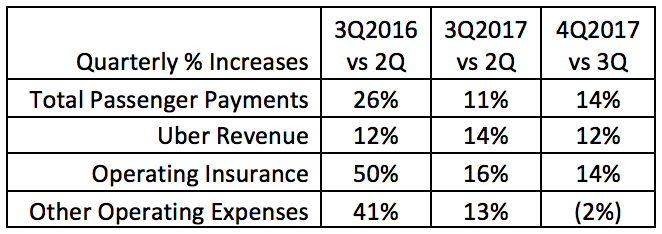

The table below shows quarter-to-quarter changes in revenues and operating expenses, based on the detailed data in Efrati’s article.

Between the 2nd and 3rd quarter of 2016, Uber operating expenses rose 3-4 times faster than Uber’s revenue (the portion of passenger payments that Uber retained). That is the polar opposite of what one would see if Uber had the kind of scale economies needed to “grow into profitability”. Between the 2nd and 3rd quarter of 2017, revenue growth rates had slowed but operating expenses were still growing just as fast. This represents an improvement over 2016, but unit costs were still not declining.

In the 4th quarter of 2017, Uber suddenly improved unit operating costs, but there is no reason to believe that Uber’s underlying operating efficiency actually improved. In part eleven of this series,[6] based on financial results through the 3rd quarter, I estimated a full year GAAP loss of roughly $5 billion. After years of steady cost increases, Uber froze spending on Operations, Sales and Marketing, Research and Development, and General and Administration. Insurance, an entirely variable cost, continued to increase in line with revenue. 4th quarter costs would have been $210-220 million higher ($800-900 million annualized) if they had continued to grow in line with revenue. These are the kind of across-the-board budget cuts big companies frequently make to stem growing losses.

Perhaps this is an initial step in the right direction, but the budget freeze cannot be said to have seriously improved efficiency unless Uber can demonstrate that it can continue to produce 10-15% quarterly revenue growth on the frozen 3rd quarter 2017 cost base. And then Uber needs to find another $4 billion in cuts..

Twitter just announced profit gains from similar (although larger scale) cost-cutting efforts, but press coverage was largely negative, noting that the cuts threatened the product and market development efforts critical to the long term survival of any rapidly growing technology-oriented company.[7] But unlike Twitter, Uber is a younger, less-mature business that has not yet demonstrated the sustainability of its business model. Twitter’s cost cuts actually produced GAAP profits. By contrast, Uber needs to make another $4 billion in cuts to reach breakeven. Twitter went public in 2013. If Uber wants to go public in 2019, it needs to be able to show that it is continuing to invest in future growth, and that rapid growth will continue to drive margin improvements for many years. Uber’s attempt to cut costs in order to marginally reduce short-term losses directly undermines that narrative.

Is Uber artificially inflating its top-line revenue growth claims?

All previous releases of Uber revenue data were limited to the top-line “Gross passenger payments” (the total money paid by passengers) and “Uber revenue”, the 20-30% of that total retained by Uber. In past analysis, I had assumed that the difference went almost entirely to drivers, but the newly released data shows this assumption is not true, and that Uber may be inflating the top-line revenue number.

In 2017, roughly $3 billion[8] of this revenue was “Refunds, Taxes and Fees” or “Rider Promotions.” Government charges and fares that are refunded should not have been included in the original gross revenue number. The “Rider Promotions” item is more problematic.

If Uber offered discounts, the higher fare (that the passenger did not pay) appears to be included in gross revenue, while the promotional discount is a separate offset.[9] These numbers do not affect bottom line P&L calculations, but inflating the top-line gross revenue number directly supports Uber’s desire to show the strongest possible passenger demand numbers. Uber has steadfastly refused to release any numbers (such as market-specific fare and yield trends) that would meaningfully document whether (or where) its revenue performance might actually be improving.

Uber cut driver compensation by $2.2 billion in 2017

The new data allows one to more precisely calculate recent Uber cuts in driver compensation. In the 2nd and 3rd quarter of 2016, 78% of gross passenger revenue went to “Driver earnings and bonuses.” By the 3rd and 4th quarters of 2017, Uber had unilaterally imposed driver compensation cuts that reduced this to 72%. If the higher 2016 rates had remained in force, drivers would have gotten $2.2 billion more in 2017, Uber’s revenue would have been $2.2 billion lower, and Uber’s GAAP losses would have been much higher than $4.5 billion.

It is perfectly reasonable for reporters to consider year-end financial results in the context of Uber’s drive towards profitability and an IPO, but reporting on Uber has steadfastly ignored drivers (and the vehicles they provide) even though they are far and away the biggest component (85%) of what passengers are paying for.[10] Uber still needs $4.5 billion in profit improvement, but it is unclear that it has much scope to reduce driver compensation much further. Driver turnover has soared. There are growing anecdotal reports of drivers forced to sleep in their vehicles. Khosrowshahi has aggressively publicized efforts to repair relationships with its drivers. Unless Uber achieves quasi-monopoly control of taxi driver jobs, it is difficult to see how Uber can continue to take larger and larger shares of passenger fares.

Uber’s narrative in 2018

Uber has always been a narrative-driven enterprise. Uber hopes that people overlook the fact that its previous narratives about Uber’s powerful, cutting-edge technological innovations, and its unstoppable march to global industry domination have been exposed as nonsense.

Its current narrative seems to focus on three points; (1) everything bad you might have ever heard about Uber was entirely the fault of Travis Kalanick, and now that he’s gone all those problems have been completely solved; (2) Dara Khosrowshahi is already doing great things to restore the financial promise Uber always had; (3) the core business is still growing strongly and we are marching steadily towards profitability and a 2019 IPO.

As discussed at length in this series, Kalanick personally drove every aspect—good and bad—of Uber’s business model for eight years. Uber could not achieved its meteoric growth without the monomaniacal, hyper-aggressive culture Kalanick created. No one can explain how the bad behavior that culture spawned can be surgically removed from the rest of the business model, or how a less monomaniacal culture can rapidly fuel both strong growth and billions in profit improvement.

While it is too soon to judge his performance, Khosrowshahi has yet to say or do anything to suggest he actually has a plan that will successfully fuel many years of continued growth and the billions in needed profit improvement. Nonetheless, Uber continues to make major efforts to portray him as someone who has already driven major financial gains.

In reality, Khosrowshahi had little to do with the SoftBank investment or Google’s failure to achieve a major victory in its IP theft lawsuit. The SoftBank plan was established by Benchmark. Google simply didn’t have clear-cut evidence that Uber had incorporated stolen IP into its driverless car designs. The Google lawsuit settlement probably could have been achieved months ago, but Uber orchestrated a process that maximized Kalanick’s public embarrassment, and allowed Khosrowshahi to play the role of the “responsible adult” that made all the problems go away. Next year’s P&L will benefit from not having to spend any more money to defend the Google lawsuit, but these gains should not be attributed to Khosrowshahi’s management skills, or improvements in Uber operational efficiency.

Most importantly, the P&L data simply doesn’t support the “major progress towards profitability and IPO” that most press reports highlight. Yes, improvements have certainly been made and will continue to be made at the margin, but sustainable profits will require a combination of much bigger cuts to driver compensation, much bigger cuts to Uber’s own costs, and getting passengers to pay much higher fares. Since no one can define a path to true profitability, Uber continues to emphasize profit targets that exclude several billion of actual costs. Given Uber’s long success in managing its public narrative, the possibility that they somehow muddle through cannot be ruled out, but the available data strongly suggests that profitability mountain is too big, and many of the actions that could help reduce costs would also choke off future growth.

[1] Newcomer, Eric, Uber Quarterly Sales Rose 61% to $2 Billion Amid Heavy Loss, Bloomberg, 13 February 2018

[2] Efrati, Emir, Uber Narrowed Loss in Q4: Full Financial Breakdown, The Information, 13 February 2018 (subscription required). Efrati appeared to be the only reporter that Uber provided with detailed P&L data.

[3]Wakabayashi, Daisuke, As Uber Eyes I.P.O., Its Losses are Slowing. But They’re Still Big. The New York Times, 13 February 2018

[4] Hook, Leslie, Uber pares quarterly losses and lifts revenues, Financial Times, 13 February 2018. There may be legitimate reasons that some of the costs included in Uber’s $4.5 billion GAAP losses do not reflect its ongoing financial situation, but no one has documented the evidence here, and it seems inconceivable that the $2.2 billion negative contribution is the best measure of its situation.

[5] The economic and competitive problems with Uber’s business model are laid out in detail at Horan, Hubert, Will the Growth of Uber Increase Economic Welfare? 44 Transp. L.J., 33-105 (2017)

[6] https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2017/12/can-uber-ever-deliver-part-eleven-annual-uber-losses-now-approaching-5-billion.html

[7] For example see Wagner, Kurt, Twitter made a profit by cutting costs, not by growing its business, Recode, 8 February 2018

[8] $3 billion is an estimated full year total based on the nine months of actual data released.

[9] Airlines could inflate total revenue by calculating it as “Full Fare” times the number of passengers, and then deducting the discount to the actual fare paid. This is not done because “Full Fares” have nothing to do with actual marketplace prices, and any gross revenue numbers based on them can be easily manipulated.

[10] Taxi service cost structures are documented in section II-B of my Transportation Law Journal article.

Bad mathematics exam?

Turn the page, and change the formula to the correct one, and hope the examiner does not notice.

Uber?

Bad financials? (I’d call billions in losses bad)

Change the CEO and hope the investors do not notice the financials.

Call Uber what it really is: a venture capital welfare queen.

What a pleasure it is to read a genuine (and all too rare) piece of financial analysis.

Some typos that mar an otherwise excellent post:

“Newcomer recognizes that $4.5 billion GAAP profit was the better indicator of Uber’s current economic performance….” [I assume that should have read ‘$4.5 billion GAAP loss”]

“Google simply didn’t have clear-cut evidence that Google had incorporated stolen IP into its driverless car designs.” [Should read: “Google simply didn’t have…evidence that Uber had incorporated the stolen IP….”]

From the first, it appears Uber listed it as GAAP profit with a negative figure, but yes, I agree it is confusing as written and will revise both. Thanks!

Uber has addicted a large portion of its passenger base to unsustainable fares. the moment those fares go up to a profitable level, many people are going to go back to pre-Uber days [ driving, walking, bus, sharing rides w-family-friends]. do that and then the network crashes as many drivers won’t have enough fares to make a [ revenue – gas] profit.

don’t see how autonomous taxis can be profitable at current Uber rates. There isn’t much fat to cut.

Sure you can make money with Uber! No, not by being a driver for them, silly. Just Short the IPO.

Very dangerous advice.

The market can be in an irrational position for far longer than you have money.

There have been many industries where bubbles that are not sustainable have gone on for a few years, sometimes more, before popping in spectacular fashion.

We don’t know if this one will inflate and pop in a dramatic fashion later or pop early.

Agreed. That’s why the link points to an article highlighting the risks.

I finally got around to buying and reading Yves’ book and understand the subprime bubble a bit better. From Chapter 9:

I wonder if there’s any analog for Uber?

I used to work in subprime risk modeling and mgmt (privately held Visa/MC issuer). We made successive record profits every year I was there. I quit and took at 22% pay cut to go back to health care analytics and tech. It was just too sleazy.

Yeah, I too have read Yves book. Loved it.

There’s not enough lipstick inventory across the planet.

They just want to hang on long enough to IPO this mess onto the markets and foist it onto the non-attentive public. I had to laugh at this new CEO cat, channeling His Inner Bezos, saying “sure, we could be profitable right now if we wanted to, but at the expense of innovation and growth.”

We also have a serious shortage of pigs that would be willing to wear that lipstick.

Google simply didn’t have clear-cut evidence that Google had incorporated stolen IP into its driverless car designs.

Should read:

Google simply didn’t have clear-cut evidence that Uber had incorporated stolen IP into its driverless car designs.

No?

Wow, it’s almost like if you depend on venture capital to stay in business, you are a snake oil salesman and not an entrepreneur. Good thing we have those taxi unions to protect drivers and guarantee them benefits and a living wage! Oh wait…

Hubert – Do you believe Uber can be profitable if it replaces it’s drivers with self-driving cars?

Uber is far from being a leader in AVs (see Navigant research) and there are dozens of rivals (~40+ in CA companies testing AVs). And no driver means even fewer barriers to entry for newcomers.

AVs are no help for Uber.

Plus read the stories carefully. All are describing AVs as ones that still have drivers. Seriously. No one is talking about a fully autonomous AV any time soon, as within a decade. And what good is a less than fully autonomous AV? This is a prescription for more deaths. Having a human who is not paying close attention having to take over the car when it says “help” means a not fast enough reaction and bad outcomes.

Yeah AVs may well find a niche for long haul trucking on the “walled garden” that is the interstate. There you have traffic and road conditions that are predictable enough, and driving that is boring enough, that automated driving may well reduce accidents. Combine that with big parking lots immediately off the interstate where drivers could get in and do the local driving just might make economic sense.

No, anyone who knows about trucking rejects this idea. Truckers do a lot more than drive. One of the most important things they do is keep their payload from being stolen. There have been long reader comments from truckers with detail as to why this is a non-starter. I should have saved them (our limited search function means they are hard for us to locate, otherwise I’d dig one or more of them out and paste them in).

Moreover, the conditions on highways are not that much more favorable. Poor lighting conditions, night, bad road markings,, rain and snow all are problems for “self driving” vehicles.

I always thought Self-Driving trucks would switch to a “Convoy” model,

where a lead driver would navigate, and the others would close follow.

The Lead driver would get paid to do that, and the convoy trucks would either have a driver sleeping or would pull into truck stops to let local drivers pick up convoy trucks.

I could see Self Driving airport shuttles (limited course, lots of clean roads, low speed).

Taxi’s and the like will take longer.

Spiegel carried an article on AV truck vonvoys. Describing prototype runs from Sweden to the Netherlands I think. Lead driver had to be actively watching and driving, trailing drivers monitoring only.

All in all sounds, like a railroad train with more labor presence and cost.

NuTonomy hopes for second-quarter 2018 launch of paid Singapore self-driving car rides

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nutonomy-singapore/nutonomy-hopes-for-second-quarter-2018-launch-of-paid-singapore-self-driving-car-rides-idUSKCN1AY2IC

Note: Singapore is a small island with only one regulator (e.g – the federal govt.). There are torrential rains, however, that’s only one type of adverse condition. Level 5 self-driving cars in the US would have many more obstacles to overcome.

Also, didn’t Uber buy 24,000 Volvo Self-Driving cars?

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-volvocars-uber/volvo-cars-to-supply-uber-with-up-to-24000-self-driving-cars-idUSKBN1DK1NH

“Self driving” does not equal “fully autonomous”. Level four self driving cars still have drivers. Only level five is fully autonomous. You’ve been misled by the captured reporting.

Congratulations on another installment in this excellent project. I can’t believe how rare this kind of sober, thorough analysis is.

What’s stopping Uber from raising prices 15%, taking most of that for themselves, and breaking even?

A respectable rate of return is a different matter, admittedly.

Their ridership would drop a ton, killing their growth story. And breaking even would require a price increase much greater than 15%.

ISTR reading (in Hubert’s series) that Uber passenger fares only cover 41% of the ride cost. Meaning the company would have to more than double fares in order to break even. Profitability would require an even greater fare increase.

According to the Information, 4Q 2017, Uber had $11,055 m in revenue, and -$1,097 m in Net Income, or 10% of revenue.

Can you explain why would they need to increase price more than 10-15%?

Higher prices would stall growth somewhat. Their QoQ growth has been ~12.5% quarterly, or about 60% annually. 4Q YoY growth was 60.6%. Fewer rides would mean fewer drivers needed, and less pressure for wage increases. And there may be opportunities to more deftly target unprofitable rides and selectively raise prices (such as when they cut reduced the unpaid time period in the wait and drive-to-pax phases).

There is a risk of much of the market switching to Lyft in the advent of sustained price increases (and Lyft is quite willing to continue the subsidy battle – I keep getting coupons from them), and then Uber’s fixed costs eat them alive. But their user base doesn’t strike me as that flighty.

FWIW, Uber raised its per mile rates 5-7% in California in September, and they’ve managed.

http://uberestimate.com/prices/Los-Angeles/

If Uber increased rates sufficiently to make a profit, then Uber rates would be nearly the same as taxi rates, and in my city, those rates would be close to some black car livery service rates as well. But I don’t think that would matter.

Uber has been in my city since the summer of 2014. In just under four years, they have trained generations (millenials, gen x-ers, second wave boomers) to use their service instead of a cab. Even if cab companies were both willing and able to learn from Uber and improve their own product, I doubt if those “legacy” cab operators could recapture their old customers and attract new ones. From the customer POV, Uber is still a new, exciting, kind of fun way to get around on the cheap, and I don’t see that going away anytime soon. “I’ll take an Uber” has replaced “I’ll get a cab” in my town. Uber has become a habit, not a choice.

The only people using traditional cabs voluntarily are older boomers, visitors from other areas unacquainted with Uber, and, very rarely, someone concerned about the insurance/liability, a topic which seems uninteresting anymore to the financial press. Rarest of all is the person who refuses to use Uber because it exploits their own drivers and puts others out of business. It saddens me to contemplate how willing we are to participate in the beggaring of our fellow human beings to the uultimate benefit of vulgarian billionaires.

I am a doorman at a large, busy hotel. I’ve watched Uber take over from cabs and eat their lunch AND dinner. Personally, it has affected my pocketbook as well: I used to get tipped for hailing cabs, and I used to make tips arranging for car services. That would amount to about 20-25 percent of my cash income. Vanished. Oh, and Uber is also teaching people not to tip.

They actually have already done that with the upfront pricing scam. Those short little 4 block rides that lazy idiots in major cities take net uber 40-60% of the fare. You paid $8, driver gets $2.80.

What on earth are they going to use to generate the growth they need?

On the other hand, it’s exactly how an MBA would think: Cut out the ‘creative’ part and let the ‘productive’ part fend for itself.