By Eugenio Cerutti, Assistant to the Director at the Research Department, IMF and Haonan Zhou, Research Assistant, IMF. Originally published at VoxEU

Chinese banks have continued to expand rapidly both domestically and abroad. Together, they constitute the largest banking sector in the world by far. This column places the Chinese banking system in a global context. Although very small relative to their domestic claims, Chinese banks’ foreign claims are substantial for many borrower countries in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean in particular. Many of these banking connections are related to Chinese outward foreign direct investment, with fewer related to trade linkages.

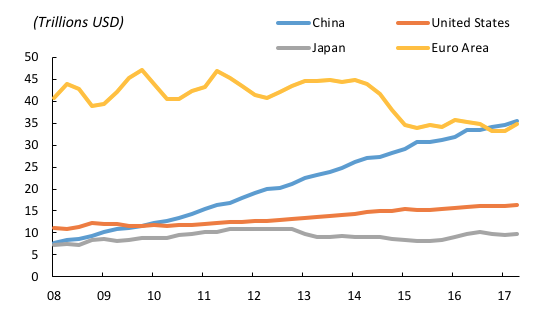

China’s banking system has been growing steadily over the past eight years. Measured in total assets, its size surpassed that of the US banking system in 2010, and even all euro area banking systems put together in the last quarter of 2016 (see Figure 1). It is now clearly the largest banking system in the world, with $35 trillion in total assets (about 300% of China’s GDP).1

Figure 1 Total bank assets for selected countries

Source: Bank of Japan, CEIC, European Central Bank, FRED.

Domestic Versus Foreign Operations

Domestic assets constitute most of Chinese banks’ balance sheets, representing about 97% in 2016 based on aggregate official data. Behind the very fast growth in domestic assets, as highlighted in IMF (2017), there is a lending boom that resulted from (among other things) a focus on hitting GDP growth targets and protecting employment while China is transitioning from a high-growth economic model based on exports and investment to one based on services and consumption.

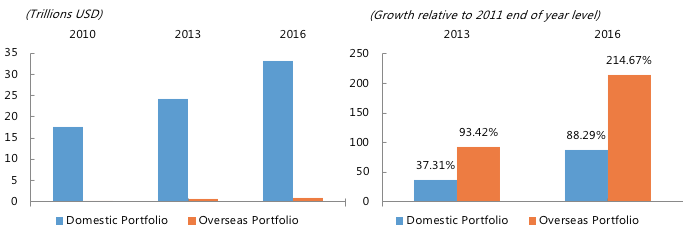

Although relatively small vis-à-vis domestic assets, the size of Chinese foreign claims has been growing at an even faster rate than domestic exposures. For example, as shown in Figure 2, foreign assets have grown more than 200% from their 2011 level, substantially increasing their upward pace with respect to domestic growth in the past three years. Given this context, the rest of the column will focus on Chinese banks’ foreign assets.

Figure 2 Total assets of banks in China, by portfolio type

Source: CEIC, Authors’ calculation.

High Financial Dependence on Chinese Banks

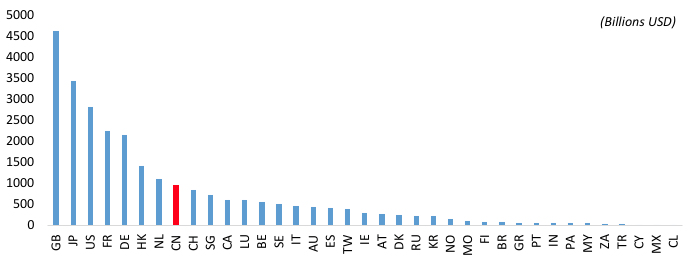

One of the recent upgrades to the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) banking statistics is an enlargement in the set of reporting countries. With China recently joining the BIS Locational Banking Statistics, it is now possible to have a relatively consistent look at China’s cross-border bank lending. As shown in Figure 3, mainland Chinese banks’ cross-border claims amounted to $970 billion as of the second quarter of 2017, ranking eighth overall globally and exceeding those of traditional financial centres such as Switzerland and Luxembourg, or countries hosting large international banking groups such as Spain and Italy.

Figure 3 Cross-border claims of BIS reporting countries, 2017Q2

Source: BIS.

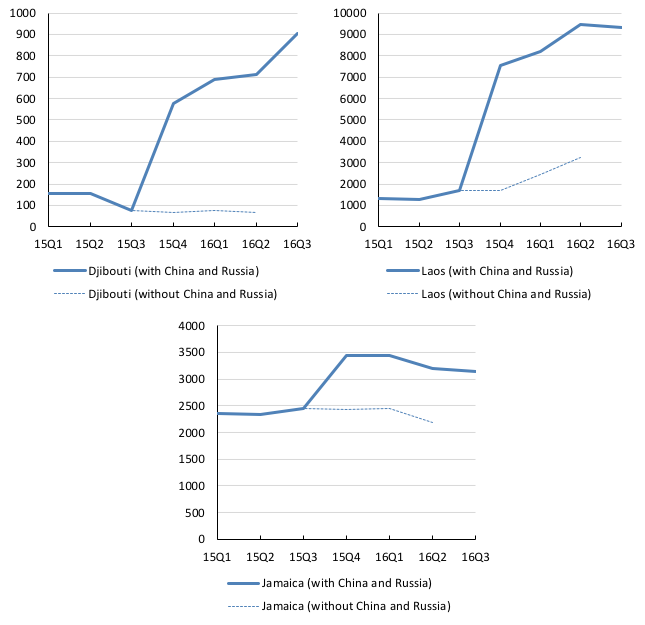

While the BIS does not publicly release China’s bilateral exposures to individual counterparties, we approximate the bilateral linkages by comparing two vintages of aggregate total banks’ claims from the BIS Locational Banking Statistics dataset.2 One vintage was retrieved on 17 October 2016, weeks before it was replaced with a new vintage of the same publicly available data, but now including Chinese and Russian bank data (we retrieved it on 19 January 2017). As shown in Figure 4, the inclusion of China and Russia triggered sharp increases in banks’ claims. For example, BIS reporting of banks’ claims on Djibouti jumped by $650 million (an almost tenfold increase) in 2016Q2. To deal with the issue that Russia and China were included simultaneously in the dataset, we exclude in the rest of the analysis former Soviet Union countries, Cyprus, and Malta (the last two being offshore financial centers), which together account for around half of the total claims by Russian banks. The remaining Russian banks’ claims are distributed across the other countries, but likely concentrated in the US, the UK, and other developed countries (Koon Goh and Pradhan 2016). Thus, our estimates are probably a good proxy for China’s cross-border claims to emerging and developing counterparties.

Figure 4 BIS reporting countries’ claims on selected countries, US$ millions

Source: BIS.

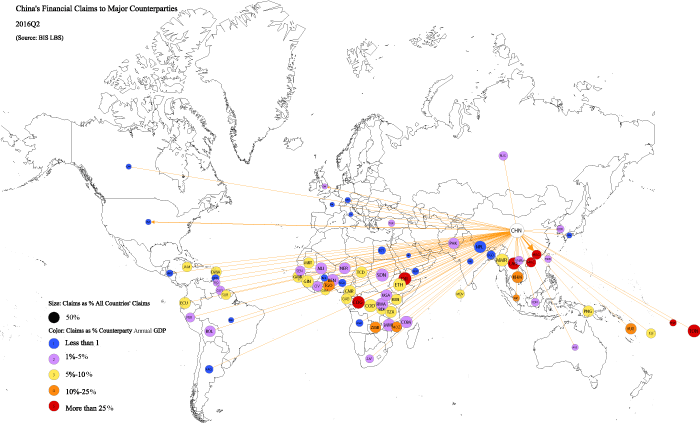

These estimates are plotted in Figure 5, which illustrates the map of Chinese banks’ major financial linkages, by displaying counterparties in the map if either they are G20 countries, or if China’s claims on the node exceed 5% of BIS reporting countries’ total claims on the same node. Not only is China connected to many countries, Chinese banks also serve as major foreign creditors for many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia (illustrated by node ball sizes above 50% in Figure 5). China’s overseas presence in the global banking network not only throws light on the expansion of China’s banking system, it also highlights the potential spillovers from China to the borrowing countries. In some cases, the claims of banks located in mainland China exceed 25% of counterparty GDP (e.g. Hong Kong, Laos, Congo, and Djibouti).

What Can Explain the Banking Relationships? The Roles of FDI and Trade Linkages

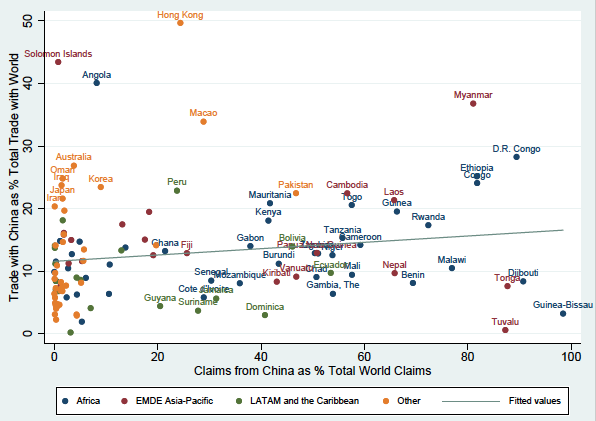

While trade finance motives may explain China’s banking linkages, the financial connections go far beyond what trade can explain. Figure 6 compares the cross-sectional relationship between countries’ gross trade with China in 2016 (as a share of trade with the world) and China’s share of banking claims on them in the second quarter of 2016. Gross trade is defined as gross exports plus gross imports. Overall, no relationship between trade and banking linkages with China is apparent. China’s trade and international banking, although related, are not necessarily different sides of the same coin. For a significant number of African and emerging and developing Asian countries, Chinese banks seem to be the major lenders, even though China has not yet established itself as a major trade partner with these countries.

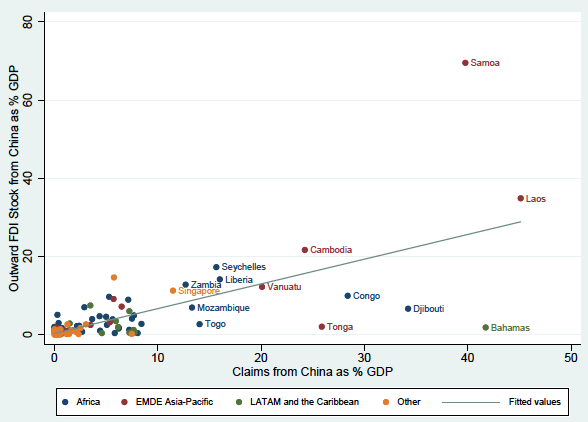

Instead, China’s cross-border lending seems to be more synchronised with its outward FDI. Overseas lending from Chinese banks has been used to fund the construction of large-scale infrastructure projects, such as the hydropower station in Laos, supported by the $1.3 billion loan from China Construction Bank (Yap 2017). Using BIS Locational Banking Statistics and CEIC data, Figure 7 presents the cross-sectional relationship between China’s bilateral FDI stocks and bank claims, both expressed as percentages of recipient GDP. Indeed, the amount of cumulative FDI tends to be large when China has a large bilateral exposure on cross-border lending.3

Figure 5 Importance of China as a counterparty, 2016Q2

Source: BIS, authors’ calculations

Figure 6 Banking and trade linkages with China, 2016

Source: BIS, Direction of Trade Statistics, authors’ calculation.

Figure 7 Banking and outward FDI linkages with China, 2016

Notes: Outliers are excluded to facilitate visualisation.

Source: BIS, CEIC, authors’ calculations.

Policy Conclusions

China’s overseas presence in the global banking system is a key feature of the country’s banking system, but it also highlights the potential for financial spillovers from China. From the borrowers’ side, the large relative estimated size of Chinese banks’ claims on several emerging and developing borrower countries highlights that potential spillovers from China depend on direct banking channels together with other traditional channels – such as trade linkages and China’s monopsony power over global commodity prices (IMF 2016).

A better understanding of Chinese banking claims might also help to explain other phenomena – for example, the current low incidence of emerging market and developing country sovereign defaults despite heavy recent external borrowing could be partly associated with mismeasurement (e.g. as information on defaults and/or arrears on Chinese loans is not available). Carmen Reinhart raised this issue recently (Reinhart 2017). We cannot directly address this, but estimating Chinese banks’ bilateral exposures is a first step to a better understanding of global banking linkages and the increasing importance of China.

Authors’ note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

See original post for references

The movers and shakers that operate that complex thing that gets personified/reified as “China” appear to have an organizing principle/prime directive, or a small set of them. Since “the future apparently belongs to China,” according to some, I wonder if anyone here, with the vast swath of experience and insight represented in this online community, could expatiate on what such principle(s)/directives(s) is/are? So the rest of us can calibrate our existential responses accordingly? And advise our children which way to turn, or run?

(Relates to forlorn hope that humankind has what I and other mopes might look at as “a viable future…”)

Building on past moves: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2008/jun/11/china.comment

Think of what China is building as the One Ball One Chain China Prosperity Sphere.

China’ Prime Directive, which they will never admit to until they have sprung every trap, could be put this way: The world is our Tibet. One Empire Under Heaven.

The first step in deciding what to do is admitting what we face.

So-same as ours, then.

Sorry. Forgot our leaders are pluralists, so at least 2 each of balls and chains. Preferably different colors.

Except our effort is ramping down, whereas China’s effort is ramping up. China is more likely to Tibetanize the Northwest Quadrisphere ( MexAmeriCanada) than the Northwest Quadrisphere ( MexAmeriCanada) is likely to Tibetanize China.

And neither of those things is at all likely to happen. In a strictly military sense, we still seem to be inanely ramping up, partly in response to non-existent threats, partly in response to self-created or misidentified ones. The Chinese seem mainly interested in acquiring the ability to project enough power to deter us within their immediate zone, They aren’t the ones insisting on a military theoretically capable of fighting 2 major + 1 minor wars simultaneously. And if they are busily bombing and droning the f- out of people on 2 continents I haven’t noticed it.

Economically, I see at least as much reason to fear the oligarchs running this country as I do anybody in Beijing. And the Chinese have a pretty full platter riding their end of the same social and economic whirlwinds as us. + they are presently not a loose cannon rolling around on the deck. Unlike us.

In any case, there’s no more reason to wet ourselves over this external spectre than over the Soviets who were supposedly poised to roll over western Europe and enslave everybody, or the sinister and inscrutable Japanese who were allegedly poised to dominate the world in the mid-80s, or the legions of crazed Jihadis coming to kill us in our beds. If the United States could ever manage to sort its own house, it would have little to legitimately fear elsewhere.

Might I suggest Emmon Fingleton’s “in the jaws of the Dragon” where he addresses China and explains their philosophy . He also has some strong opinions and interesting observations about Japanese stagnation.

I thought that the US banking system still had about 800 trillion in derivatives still floating around.

That’s the notional amount. Economic value is way way lower.

Good thing, we’re starting to talk about real money.

THis reminds me of the statistics out of Japan in the late 1980s that showed the Japanese banks as behemoths that dwarfed all the other banks of the world. IIRC, the largest US bank at the time made the list at 19th. This ‘size envy’ was in no small part responsible for Washington’s acquiescence to the bank mergers and consolidations of the 1990s, and we’re still living with the results of that. Thank you RObert Rubin.

Returning to these statistics on the CHinese banks, I trust them as much as I trust the Japanese bank stats from the 80s. It would interesting to get Yves’ take on this as I know she was recruited by a Japanese mega bank (Sumitomo?) around that time and had an inside seat at the subsequent degringolade. If I could short the Chinese banking sector I would.

P

There are indeed many comparisons that can be made between Chinese banking and the Japanese banks of the 1980’s. Many of the same tricks to boost balance sheets and hide debts are being used. Its detail heavy, but Michael Pettis is always worth a read for an inside explanation of Chinese banking and debt. He certainly things there is a lot of creative accounting used to make their balance sheets look much healthier than they are.

From the post

Domestic assets constitute most of Chinese banks’ balance sheets, representing about 97% in 2016 based on aggregate official data. Behind the very fast growth in domestic assets, as highlighted in IMF (2017), there is a lending boom that resulted from (among other things) a focus on hitting GDP growth targets and protecting employment while China is transitioning from a high-growth economic model based on exports and investment to one based on services and consumption.

This is key, and from the link to Michael Pettis is this.

My second reason for skepticism is one I have written about elsewhere, in both a November 2017 Financial Times article and a September 2017 blog entry. When one compares credit growth to growth in debt-servicing capacity, not only is it uncertain how quickly credit is growing in China but, more importantly, it is even less certain how quickly the country’s debt-servicing capacity is growing.

The standard proxy for growth in debt-servicing capacity is GDP growth, but this is only valid in economies in which GDP growth data is a systems output that measures the underlying performance of the economy. But this is not true of China, as I explained in the Financial Times article:

Typically, analysts assume that changes in reported GDP reflect movements in living standards and productive capacity. In China, however, this is not the case. Local governments are expected to boost spending by whatever amount is needed to meet the country’s targets, whether or not it is productive. [In China] GDP growth is not the same as economic growth.

In China, GDP is an input. Build it and they may not come. Embedded in China’s economy are an untold number of financial booby traps. Now going worldwide.

Globalization is a disaster, no matter where one cares to look.

Michael Pettis has been spewing his “white man knows better than the chinamen” for years. Look around China, what do you see–growth. America–rot, Japan–stagnation.

Is what Micheal Pettis saying not true? Here is how he explains the concept using bookshops to illustrate.

I would say it is even more than short-sighted to assume that because they share the same name, GDP as a systems input can be compared to GDP as a systems output. It is literally wrong. Because this seems confusing in the macroeconomic context, I thought maybe an example outside macroeconomics might be helpful.

Suppose one wanted to measure urban literacy as a function of a city’s size, or of the average income of its residents. One way to do so is to look at dozens, or perhaps hundreds, of cities in terms of population, or average income, and compare them with the number of bookshops in each city.

In that case, the number of bookshops, which is a systems output—generated organically by the size of the city, the rate of literacy, the income of residents, and other relevant factors— would serve as a proxy for literacy, while population or income would serve as proxies for whatever variable one wants to measure. Like with GDP, there are a whole set of problems with using the number of bookshops as a proxy for literacy, but it is a reasonable proxy, and perhaps in our case, it is the best measure that can be found. What is more, because one can reasonably assume that the problems with using bookshops as proxies for urban literacy are not systematically biased, these problems can be addressed and partially resolved by using a large sample base.

But now assume that the government passes a literacy law that requires that every city must have exactly one bookshop for every 10,000 residents—no more, no less—and there is a government agency whose purpose is to make sure that for every city there is the number of bookshops required by law. To that end, all bookshops become government-owned and operated, without hard budget constraints.

Clearly, the number of bookshops in each city has now become an input to the system of literacy and is no longer an output generated by the organic growth of the city and the underlying need for bookshops. This immediately renders the number of bookshops useless as a proxy for literacy, unless one can find another output measure that can be used to adjust the number of bookshops, perhaps the number of titles on offer or revenue per shop. Without some kind of adjustment, however, anyone who used the number of bookshops as a proxy for literacy would find his work widely ridiculed.

——————————————————-

Look around China, what do you see–growth. America–rot, Japan–stagnation.

Globalization is a disaster, no matter where one cares to look.

Pettis is reminding us that the sense of rules in China are just a sense, so look at stats and debt ledgers with a grain of salt. I have no doubt that the central bank in China can simply erase positions it no longer wants to put on ledgers (indeed, the conversion of debt into ‘equity’ may be the same thing, just dont know this yet). Who would know?

We can do that here in the US too. The Federal Reserve holds over $2 trillion of public debt, positions they bought with key strokes into bank reserve accounts. These Fed held positions could simply be erased (though to avoid unsettling all the accounting religiosity people they can agree that principal redemption amounts create a surplus that is required to be remitted right back to Treasury who had just sent them the redemption amounts, so voila, instead the Fed can erase its position as the Treasury erases its obligation to pay position, classical accounting offset). So $2 Trillion can be erased easily even as the nongovt actors have the cash in the economy or are ready to put more recent issues cash into the economy via bank lending accounts with businesses.

The Japanese banks were doing the simplest of lending. Zaitech didn’t get started until the later 1980s and the banks didn’t blow themselves up on that. They blew themselves by being willing to lend 100% against the grotesquely inflated appraisals of urban land, particularly commercial property in Tokyo.

It is hard to stress enough how utterly fictional these values were. Land was NEVER sold, so there was no market. First, the taxes were catastrophic. Second, the land was seen as sacred, so selling it would be like selling a child, or admitting you were going bankrupt.

Residential loans were just as inflated. To give you an idea, I saw an apartment in Tokyo in 1989 (it was a very big deal to be invited to someone’s home). A 800 to 900 foot three bedroom. I didn’t see the bedrooms but they were tatami mat sized. A not large combined living-dining room. Galley kitchen only one person could work in. One full bath, again not large. It was considered luxury housing, in a nice complex with trees, inside the Otemachi line (as in pretty close in).

The market price at the time? $5 million.

The Japanese were also doing dumb stuff like participating in LBO loan syndicates when they had no idea what they were doing. I recall being yelled at because I couldn’t make $30 million, like the syndicated loan team did, lending $500 million to Campeau.

The Campeau deal went totally bust.

So the loans were real. They were made. It’s just that most of them were stupid and went bad.

I feel certain the Chinese learned from all this. They absolutely understand they are just putting out liquidity and direction that truly serves to lift huge number of people out of subsistence levels, and while their society matures in its use of markets and pricing for transactional level signaling. I also feel that they are aware of their ability to pump out debt to get the more rapid flow – and then just erase it from their books when it makes sense (debt does discipline recipients of the monies, forcing them to produce and sell and organize so that a slice of their flow goes back to the lender).

When the uses put to this flow are simply lacking in economic reality, just erase the debt, like early civilizations, the burdens are lifted by the public itself via its governing power/institutions so burdens are lightened as efforts begin anew.

This is why I come here, too hear people such as yourself unabashedly speak.

“degringolade” — had to look that one up. At first glance, I thought it referred to the reconquista.

Smart geopolitics, wonder what currency the loans are denominated in? Besides controlling sources of energy and raw materials, China appears to rapidly be making inroads in establishing the Yuan as a key global reserve currency regardless of whether China is using this as a vehicle to in part recycle its $USD trade surplus.

Hidden costs to dismantlement of the State Department, military as the default solution, and a “shitholes” view of others.

It is my understanding that the US benefits from being the unit of international exchange but I do not know what those benefits are. Nor do I know what damage would be done if we lost that status. Can anybody clarify that or point me towards a source that would clarify it?

Thank You

US will hold reserve currency so long as foreign savers demand it for their mattress. If and when they prefer yuan, chinese trade surplus will turn to deficit and they will export jobs as their consumers enjoy a higher standard of living.

None of the current major exporters want to convert their surplus to deficit, even though their residents would enjoy a higher standard of living.