By Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Professor of Economic Geography, London School of Economics. Originally published at VoxEU

Persistent poverty, economic decay and lack of opportunities cause discontent in declining regions, while policymakers reason that successful agglomeration economies drive economic dynamism, and that regeneration has failed. This column argues that this disconnect has led many of these ‘places that don’t matter’ to revolt in a wave of political populism with strong territorial, rather than social, foundations. Better territorial development policies are needed that tap potential and provide opportunities to those people living in the places that ‘don’t matter’.

On 16 October 2008, Tim Leunig, an economist who at the time was working at the CentreForum thinktank, stood in Liverpool’s Cathedral and told a crowd of bemused and worried Liverpudlians that, economically, their home city’s time had passed. Cities and counties in the north of England had “slipped back relative to both the national average and Britain’s most successful towns”, and “regeneration policy [had] failed to regenerate towns” (Leunig 2008).

Despite massive public expenditure by successive governments to promote development in the north of England, the results had been dismal. The economic gap between a prosperous south of England and a declining north had widened (Martin et al. 2016). Development policies were not working, and there was a need to rethink development strategies for those areas of the UK that were lagging or declining (Leunig 2008).

The proposed solution was simple. First, focus on the regions of the country that were prosperous and dynamic (London and the southeast). Second, allow “people in Liverpool, Sunderland, and so on” (Leunig 2008) to move to more affluent places to take advantage of the opportunities on offer.

Leunig demonstrated considerable courage by standing in front of what would have been a polite but mostly hostile crowd. What Leunig did not realise, however, like many academics that preceded and have followed him, was that telling people that where they lived, and where they felt they belonged, did not matter would create a reaction.

The worldwide reaction has, however, come from an unexpected source. In recent years, some of the places that ‘don’t matter’ have increasingly used the ballot to rebel against feelings of being left behind, of lacking opportunities or future prospects. Researchers who focus on interpersonal inequality (such as Piketty 2014) might have predicted this reaction – for which there had been precedents in Thailand and some Latin American countries (Roberts 1995) – would set rich against poor. Instead, lagging or declining regions voted differently to prosperous ones.

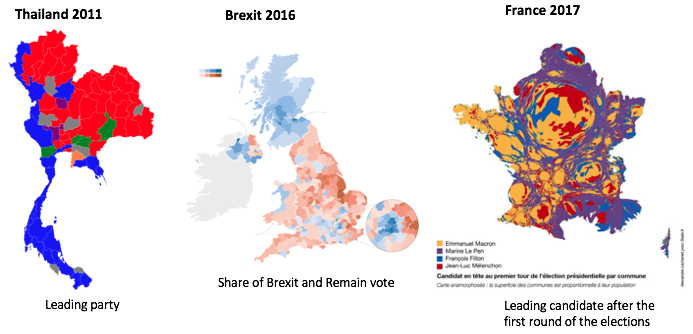

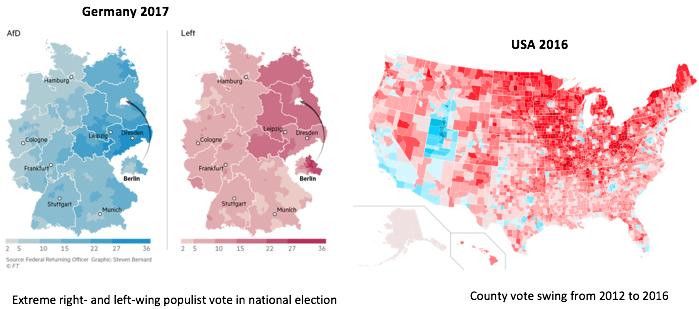

We can see this revenge of the places that don’t matter (Rodríguez-Pose 2018) in the 2016 Brexit vote in the UK, the 2016 election of Donald Trump in the US, the 2016 Austrian presidential election, the 2017 French presidential election, and the 2017 German general elections. It threatens to derail the economic and social stability that has helped create the prosperity of the most dynamic cities and regions.

Figure 1 The electoral reaction of the places that don’t matter

Source: Rodríguez-Pose (2018).

Are We Surprised?

Although there will always be claims that a worldwide emergence of populism was on the cards, politicians and mainstream academics have been caught by surprise. They were unprepared for this surge of populism, by its ascent to power, and by the challenges it poses. With a few exceptions, we have been looking at the wrong types of negative externalities, ignoring one important form of inequality, overestimating the capacity and willingness of individuals to move, and overlooking or dismissing the economic potential of many lagging-behind areas.

- The wrong type of negative externalities. Research in economic geography and urban economics shows that agglomeration, for all its advantages, can trigger negative externalities. Traditionally, we consider high land rents, congestion, and pollution as the main negative externalities. While they can certainly stifle development, the real cost has been unexpected social and economic (real or perceived) distress in many non-agglomerated areas.

- Considering territorial inequality as almost irrelevant. Worries about inequality before the outbreak of populism were mostly about interpersonal inequality (Sassen 2001, Piketty 2014). Since the 1970s, wealth has concentrated in an ever-smaller share of individuals at the top of the pyramid, leading to a growing economic polarisation of society. Yet, in the Brexit vote and in the elections of Donald Trump and Emmanuel Macron, there is little evidence that interpersonal inequality played a decisive role. Populism was not most popular among the poorest, but instead in a combination of poor regions and areas that had suffered long periods of decline. The places that don’t matter, not the ‘people that don’t matter’, have reacted. Interpersonal inequality still matters, but the challenge to the system has come from neglected territorial inequalities.

- Overestimating the capacity and willingness of individuals to move. When Tim Leunig encouraged Liverpudlians to move to the southeast, he was expressing the assumption in urban economics that mobility is costless, or at least that it is preferable to move than to stay in a place where there would be a limited chance to find a job (Kline and Moretti 2014). But encouraging mobility, or making it easier to find housing in dynamic areas, would be unlikely to increase the number of people who move to them. Those that stay in lagging or declining regions may be unlikely to relocate because of emotional attachment to the place where they live, age, or lack of sufficient skills and qualifications, among other reasons.

- Overlooking the economic potential of lagging-behind and declining areas. The places that don’t matter have often been characterised as ‘rustbelts’ or ‘flyover states’. Economists argue that “subsidising poor or unproductive places is an imperfect way of transferring resources to poor people” (Kline and Moretti 2014). Nevertheless, few lagging and declining areas have no economic potential. Many once-lagging areas are now leading regions, while former leaders have sometimes declined. Barca et al. (2012) argue that “tapping into unused potential in intermediate and lagging areas is not only not detrimental for aggregate growth, but can actually enhance both growth at a local and a national level”. Shifting attention from places in need of support to more prosperous and dynamic ones also causes distress and resentment in the neglected spaces, sowing the seed for revenge through the ballot.

Dealing with the Revenge of the Places that Don’t Matter

The revenge of the places that don’t matter – reflected in the rapid rise of populism – represents a serious and real challenge to the current economic and political systems. The stakes are high, but there are few solutions.

Doing nothing is not an option, as the territorial inequalities at the root of the problem are likely to continue increasing, creating social, political and economic tensions. Internal migration, as proposed by Leunig, may only be feasible for those with adequate skills.

Gambling on large agglomerations is not a sure bet. In developed countries, big cities are not always the most dynamic engines of growth (Dijkstra et al. 2013). In developing countries, urbanisation without growth is increasingly the norm (Jedwab and Vollrath 2015).

Decentralising and devolving power to less developed cities and regions has also had disappointing economic outcomes (Rodríguez-Pose and Ezcurra 2010). Sticking to existing social and welfare policies can result in permanently dependent populations and territories, possibly stunting economic growth and leading to a rise in social and political tensions.

Development policies for lagging and declining areas offer the most realistic option. This does not mean more policies, but better policies. These policies would be aimed at maximising the development potential of each territory. They would be solidly grounded in theory and evidence, combine people-based with place-based approaches and empower local stakeholders to take greater control of their future (Iammarino et al. 2017).

There is no guarantee that these policies will reduce the risks, but they are the best chance to enhance the opportunities of individuals and workers to thrive and prosper, regardless of where they live. Ignoring these policy options would bypass economic development opportunities and lead to a world in which the revenge of the places that don’t matter will be fully justified as continued economic, social, and territorial conflict. This would erode the economic, social and political foundations on which we build our current and future well-being.

See original post for references

“This would erode the economic, social and political foundations on which we build our current and future well-being.”

I don’t find myself in the “we” he, apparently, speaks for.

I don’t understand your reaction, He says that the decline of communities is important and effectively, that the usual economist handwaves of “let them eat training” or “they really need to move where the jobs are” don’t work. He says that figuring out how to revive these communities is important but that current policies have failed. He says that’s not an excuse, we need to find better policies and effectively says that will probably take some experimentation.

His last sentence is wonk-speak for telling the people who think they don’t have a vested interest, that they can let these communities fail, that they are wrong headed and it will blow back and erode their own legitimacy and standing. And you object to this? This is pretty strong medicine by the normally bloodless standards of hard core economics pieces. Have a look at the post launching at 10:00 AM from Bruegel for a contrast.

Yves, I think he means that the economic system in its current state belongs to the wealthy and their neoliberal shills. So if it suffers, he says welcome to hell. Those who feel left out often relish schadenfreude.

I *think* – would be better if Witters comes back and explains for themselves, of course – he/she is saying that she/he does not have a personal sense of “current and future well-being”. It’s already eroded.

Witters is seeing a pretty speech about tomorrow but needs to eat today.

Isn’t rural depopulation and concentration into human habitation zones pretty clearly the plan being worked? I don’t think that Agenda 21 is theory. This is the ‘slow’ version of forced resettlement.

Good, solid piece. I’m reminded of the conclusions of a very different writer, Lewis Mumford, whose The City in History I found quirky (all that ink spilled over the rutting of nobility at Versailles!) but was pretty insightful. I may be misremembering (I read the book about 40 years ago), but he pointed to the 19th century move of poor, unskilled labor in Scotland to a few cities that resulted in life expectancies there in the 20s. His conclusion was that moving people to cities wasn’t an answer, unless the cities were designed and managed in such a way as to integrate them into its community at a sufficiently advanced level to handle all their needs. Industrial Britain merely used them as disposable fodder. My codicil would be that today in the US they’re not generally going anywhere, and viewing politicians who see them as a basket of deplorables with disdain.

The has been little written about the appalling social, and therefore economic, cost of relocation. First is the loss of territorial and functional familiarity. Learning how to get on in a new place is far from being inconsequential.

Then there is the weakened social network requiring calling uber rather than the retired neighbor who enjoys the chance for social contact, for example. Not knowing neighbors is also not inconsequential.

Finally (in my mind-top) is straining the familial bonds of caring for elderly parents at a distance; again poorly substituting paid for personal care.

I have not seen studies that attempt to put a dollar amount on these costs; it believe it would be massive.

I’m from “a place that doesn’t matter” – Burnie, Tasmania. It has been slaughtered by neoliberalism and deindustrialisation over 40 years. It is flooded in drugs and despair. To try and live there sears the soul. All this was done to my town for by and for those enjoying their “current well-being.” So I have a pretty damn good idea of what their “future well-being” can be expected to bring.

Sounds like you must be a big fan of Colonel Klink aka Eric “aids and” Abetz. Me too! /s

Reviving these places is not important, getting people to leave to get to where greener pastures are is paramount. These places will never be major additions to the now global economy. The people that live here dont even want to entertain that they are living in poverty due to their own choices and refusal to do what is necessary. When ways to improve are introduced they are usually voted down so it again comes down to their own choices. I live in such a place as I am retired and dont need the locals to survive. Its really a sad state of affairs.

perhaps you should read the article again. It pretty much says the exact opposite of your comment.

The Electoral College worked as intended.

Indeed it did. And I sure don’t see any DNC-led campaign to abolish it.

The desire to improve their chances in the presidential elections is outweighed by their aversion to seriously funding and supporting the state operations in hinterland red states.

And potentially more important, the inability or reluctance of the democratic party to fund and build strong operations in the battleground states; Those states that the party potentially stands a much better chance of winning the electoral college and congressional majorities with strong economic policies and effective messaging of such.

Yes. The coasts have been subsidized. The Defense Dept funded tech and the MIC so that it could survive competition and continues to pay for all kinds of deep basic research, which is concentrated on the coasts. The same goes for the NIH/NCI with big pharma. The money center banks on the coasts get first access to inflating money supply thus benefiting from the Federal Reserve System. The middle of the country has been hammered as the manufacturing base is made to compete with slave labor and close to zero cost regulatory regimes. The rust belt was destroyed by the coasts and now suffer from meth and opiod epidemics plus lack of capital. The family farmers were killed by hammer blow of the Fed’s inflationary policies of the 70’s which led to debt and contraction in the 80’s–foreclosure by corporate farming financed by the banks again at lower costs.

I know less about the UK but I would bet that the EU and finance dynamics have a lot to do with disparities.

I would not blame the EU for UK disparities. These are much more the fault of the UK government. Outside the Euro zone the UK has much flexibility on fiscal policy. But it decided for political reasons largely to pursue austerity. That and a commitment to low or even zero taxes for the rich has produced a witches brew.

I appreciated the article, but he only touched on the idea that these territorial rivalries only get worse over time, because policy is generally driven by the people in the areas and industries that are growing. More and more people in the flyover states see themselves marginalized by those on the coasts, especially as small farms give way to big ag and manufacturing goes overseas. Some feel like they are being treated as nothing more than the garbage dumps for the well-to-do, and not without cause.

The article struck me as very sensible.

A few years ago my father’s cousin died aged 99. I went to his funeral in the North East of England. During that day I took 3 taxis. Each driver asked me my opinion of Mrs Thatcher (I am not a fan ).Each one said ‘we all hate her up here ‘. This was no surprise to me but reinforced my perception that things were badly awry in the UK.

Those who have benefited from globalisation have done far too little to share their good fortune with the losers. If this doesn’t change there will be more Brexits and more Trumps IMO. That will only add to our problems.

Why would those who have benefited from globalization share their good fortune with the losers . . . when their good fortune was all looted from the losers to begin with?

They might at least take with the ‘left’ hand while they give with the ‘right’ hand and wink at the difference in their pockets. It’s in-your-face disrespectful to just take without at least putting on a show of ‘magic’.

“Even the dogs get the crumbs from the master’s table”

After Maggie died, “Ding Dong The Witch Is Dead” hit #2 on the official sales charts and BBC Radio 1 was forced to play 5 seconds of the song during their weekly count down show.

Had the exact same thought last night and even played it. She is still hated for the destruction of communities that she wrought by so many people. Did you hear that they wanted to erect a giant statue of her at Westminster (https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/jan/23/plans-margaret-thatcher-statue-westminster-rejected) but which the council wisely voted down.

You would have to protect such a statue 24-7 from protesters and vandals all year round and who would pick up the tab for that one? If the 24-hour guard outside the Assange embassy in central London has cost taxpayers more than 10 million pounds ($20.8 million) by 2015, how much would the statue’s guard cost each year?

It also would be a brilliant focal point of protesters and unite them in a way that no other statue ever could. I’m sure that the government would appreciate that aspect very much.

I predict that song will once again see a sudden increase in popularity at some time in the short to medium term future. On an entirely unrelated note, does anyone know if the Rodham bloodline has a history of longevity?

Economists tend to worship GDP so any policy that is increasing GDP is seen as good. Standardisation, centralisation and massproduction increases GDP. Keeping all regions alive might decrease GDP and might increase quality of life for people.

Redistribution policies through taxation and government spending can only do so much (as claimed by the author and supported by studies). The ‘populist’ introduction of trade-barriers is actually something that would work in keeping regions alive. Locally produced goods and services keeps regions alive.

Oh, and the tension between the ‘productive’ regions isn’t only seen in reluctance to redistribute ‘wealth’ between regions it is also seen when migrants are not welcomed into the ‘productive’ regions. Downward pressure on wages, increased competition for government provided services and higher cost of housing can be blamed on even migrants from within a nation….

& when the GDP increases are captured as they are now then the rallying cry of ‘It is good for GDP so we have to do it!’ might not be supported by many more than the IYI.

Good analysis, but the word salad policy prescription in the next to last paragraph sounds like something

from the campaign platform of a DLC or New Democrat:

” … not … more … but better …maximising … potential … evidence … people-based … empower local stakeholders to take greater control of their future …”

The devil is in the details. How does one do this without just getting a gravy train for the well-connected

with no long-term benefit to the “territories”?

yea it sounds nice and unobjectionable but … Plus can the global trend to urbanization really be stopped? I’m not saying it’s desirable but is it really stoppable?

You don’t have to stop or discourage urbanization to allow better lives for people in the sticks. Policies can recognize and foster synergies between cities and the land that benefit both sides of the coin. The trick is in imagining effective actions that don’t task poorer people in wealthier areas with shouldering costs.

Seattle or Atlanta might impose a food tax that takes into account the externalities of production by being lifted, in part or whole, for organic growers and free range ranchers who deliver fresh goods (and employ a skilled, well compensated workforce in the local countryside to do so.) The city’s less crunchy, poorer poulation would pay the price, losing Tyson Farms for $2/lb. Overall health is better with all sorts of opportunity in play for regional industry to flourish. But you have get clever with fiat to assign costs in a way that doesn’t alienate a population.

Its interesting that the article uses Liverpool as an example of a ‘left behind place’ while citing the Brexit vote – Liverpool in fact voted 58% Remain, one of the strongest pro-EU votes in England (outside of London). In comparison, Chester, a very prosperous nearby town, voted for Brexit. In reality that map more accurately reflects the importance of English nationalism in the Brexit vote than economic divisions (Liverpool probably being the least ‘English’ English city).

I’d also question the use of Thailand as an example – there are very strong historical and cultural and ethnic differences between the north of Thailand and the south, which has had a huge influence on voting patterns. The ‘north’ has always been neglected by the combination of the more royalist (i.e. feudalist) south, but to an extent it was the rise of the deposed Sukampol Suwannathat that catalysed the political divisions in the country.

But the general point is true – there has been a retreat over the past few decades from the notion that it is a fundamental responsibility of central governments to look after lagging regions. In the 1950’s to 70’s for example in the UK, vast resources were put in to regional development – you can see it still today in what now looks like a hazhazard spread of universities (the old polytechnics), often in odd out of the way places like Bangor or Coleraine. That ended largely with Thatcher (although even under Thatcher large amounts of money was spent on certain types of urban regeneration, although this was supposedly private sector led). Its not altogether clear I think whether most of the money thrown into decaying regions has actually been worth it. Its a bit like the old advertising adage – half the money in advertising is wasted, its just that nobody knows which half.

Liverpool is an interesting example. At various times, the city has suffered from overt neglect, with occasional bouts of regeneration enthusiasm. It is an amazing city, with stunning architecture and a very vibrant cultural life – helped of course by the large amount of cheap space and very cheap housing. If you can get a public job there, its one of the best places in Britain to live, as you could buy a fine Edwardian 3 storey house for the price of a squalid studio flat in London. But its still in chronic decline. But it all can’t be blamed on lack of investment as other northern cities such as Manchester and Leeds have done relatively well over the same period. Perhaps its a cultural thing (as all Manchester people will insist, its all down to Liverpudlans being bone idle whiners), or perhaps the economics of agglomeration have allowed the two biggest cities in the north of England to dominate the others.

While scale isn’t everything, the reality is that agglomeration benefits are very real. Its why London continues to grow despite huge costs and terrible housing. Its a key reason I think why many modest sized urban areas like Liverpool refuse to grow. Its not just a matter of the number of people – research indicates that mobility within the area is very important – hence megacities with terrible public transport like Manila or Lagos or San Paulo don’t get the benefits, while Shanghai, New York, or Tokyo still prosper.

The reality is that regional or city regeneration is very hard when the original reason for the cities existence no longer exists. Cities almost never disappear (except when there is ecological collapse, as with Mayan or Khymer cities) – many old cities in Europe lost their raison d’etre a millenium or more ago, but are still there (places like Avignon, or the many bastide or bishopric towns). Others seem to keep on reinventing themselves (like Berlin). I’m not sure there is any easy answer.

To be fair, if you use Liverpool as an example you get to use the word “Liverpudlian” and who can resist that?

Its sounds even better in a Liverpudlian accent…

Form what I know from my visits to the area besides ” Mock Tudor ” Chester itself, which does itself have an extensive publicly housed population, it is tied to a few places in which the apparent prosperity isn’t shared – Ellesmere Port for instance which comes under I believe Chester West. The constituency of Chester was always a Tory stronghold up until recently, so perhaps that is a sign of demographic change, with perhaps Liverpool exporting Labour voters. I recall from my travels around there that it is a fairly complicated patchwork & the Wirral which voted Remain at it’s core is a scene of industrial devastation, but also has something of a posh commuter belt.

Ellesmere Port which has a large car plant may well have shot itself in the foot.

PK,

A pleasure to see you and the ‘usual suspects’ posting on this linked article, which details surprisingly that the forgotten masses are using the ballot box to ram home a message to their betters – just a quick note on Liverpool, which seemed an outlier Brexit vote compared to other depressed regions. Maybe the Irish influence had an impact, or, perhaps gentrification that has been on going since Thatcher’s time in office, I say this because in the mid-80’s I actually was at Liverpool docks supplying laser lighting effects for the regeneration of that area, which of course followed on from the riots that took place in the early 80s – Manchester voted remain too, whilst Greater Manchester voted Leave, as did Cardiff (Remain) with its environs also voting Leave.

I mention my own capital city due to the fact I was listening to the latest Podcast from the lads at DesolationRadio, who’s guest this instalment was a working class Sociologist – her observation on Brexit chime with the above post, namely, that the working class don’t care much for sticking plaster solutions, nor being told what to do by their social betters – anti-immigration feelings did not figure in her interview, although, anything to stick two fingers up to our betters figured greatly. I highly recommend a listen if you have time: https://soundcloud.com/desolationradio/getting-by-and-gentrification-with-lisa-mckenzie

Thanks Christopher, that podcast looks interesting, I’ll have a listen tomorrow.

I briefly lived in Liverpool (just a couple of months) in the late 1980’s, and still have a lot of affection for it. Last year I found myself in the city on a Sunday evening, Monday morning, waiting for the 4am ferry to Dublin and spent that time spending many hours walking along the docks and through the city centre. so much of Liverpool is wonderful – the quality of some of the 19th Century commercial buildings is mind-blowing – as are the many scars of decay and (in particular) ill-judged regeneration projects, such as the dull suburban housing built around the Anglican Cathedral (and what a building that is). I had forgotten just how vast the docks are between Liverpool and Bootle – its so depressing nobody has come up with a good use for it all.

Your point of comparing to advertising is crucial. The problem I see is that no-one knows in advance what will work, so you need to throw a lot of money on the development, for quite some time (you can’t change skills overnight). Press and media have an in-built bias to where the throwing of the money fails, and this builds a feeling in the rest of the country/whatever of “we get taxed to pay those lazy -insert-your-word-here!”. Which few politicians disagree with, and even fewer are willing to go against until the “lazy XYZ” are in the majority.

Liverpool is a good example because it has been a victim of central government “regeneration” — which, invariably and inevitably, means paying consultants from London or Manchester to come and tell the Liverpudlians what to do. 2008 was the case in point: it was the year in which Liverpool was European City of Culture. The Culture Company was run by a Mancunian, who hired a New Zealander to run the cultural festivities. The New Zealander hated the city and never showed up. She was fired, but not replaced. The cultural celebration, such as it was, involved importing artists and acts from outside the city to entertain the natives — even though the city had won the award on the basis of the unique cultural contributions of the people who lived there (think Beatles, a dozen other rock’n’roll bands, the Liverpool Poets, the Everyman, the Playhouse, the Liverpool Philharmonic, and three universities).

“Regeneration” is the imposition of foreign (in this case London) values on a local community which rejects them — another example would be William Walker, the “Regenerator” of Nicaragua in the 1850s.

65 million people live in the British Isles. 15 million of them live in London, where the vast majority of cultural funds are spent. Boris Johnson burned through 46 million pounds of taxpayers’ money on consultancies for a “Garden Bridge” over the Thames – which will never be built.

If only the regenerators could be persuaded to stay at home, and just send us the dosh!

BTW…

“Walker” with Ed Harris is one hellova film, a must see.

Not so long ago I noticed a position in Acton, London which I was tempted to apply for. The salary was £ 45,000 pa, with good benefits. I spent probably a whole day looking at the cost of houses, rents & the commuting costs within a radius of around fifty miles. My conclusion was that in comparison to where I am now living, the actual salary would be around half of what it would be actually worth & would involve living in a rented poky flat with the dismal prospect of a long commute.

I do not understand how it could be seen as sound policy, to expect the likes of the majority whose expectations in terms of salary would likely be often much less than the above, to even consider such a course of action, particularly if they have family & roots. Perhaps single youngsters could give it a go if they rented a room or a rabbit hutch, but the low skilled would also likely have to compete with immigrants, who get to do the menial stuff & live in death traps.

As for regeneration in Liverpool & elsewhere based on the ” Guggenheim ” Bilbao total waste of time, morphing into ” Garden Festivals ” under the Tories & then taken up in differing incarnations by New Labour – Jonathon Meades nicely sums it all up as basically fancy whitewashing that did sweet bugger all for those it was supposed to help. Some years ago he made a film called ” On the Bandwagon ” created around 2009 which as he admits was totally ignored. The film can be found on Vimeo & here is a short update he wrote recently.

https://www.spectator.co.uk/2017/10/cultural-regeneration-is-a-racket/

Thank you, Eustache.

Further to your link, http://davidaslindsay.blogspot.co.uk/2017/12/the-capital-offences-of-boris-johnson.html is also good.

Thank you Colonel.

I look forward to reading that.

BTW my bad – The film is actually titled ” On the Brandwagon “.

I also know of a group of relatively young sculptors for film companies who are struggling in London while now earning around £1400 per week.

They are always attempting to come to NI where they would earn around £ 500 per week less.

I personally find myself in the oposite situation. There is no work 2 to 3 hours away so I’m stuck working in urbanized SF Bay Area but housing costs are slowly killing me.

Can’t afford to stay, can’t afford to leave.

People were working in the Bay Area and living in Sacramento when the last two booms ended which is roughly 90 miles each way. As just driving 20 miles can take over an hour during a boom time “rush hour” that commute is insane.

The Bay has a similar feel as before, so I think my rent will not be going up, or even go down (Gasp!), which for me is good I guess as a college student, but it is awful seeing people lose their jobs and homes.

Yes, moving can be cripplingly expensive. Even within a region – back in the late 1990’s I was working in Essex and I had the offer of a job I really wanted which was based on the fringes of London in Sussex. But I was earning very little and the other job wasn’t much better. I simply couldn’t change job because I couldn’t afford to move within easy commuting distance of the new job.

It is one thing that has convinced me of the incredible power of momentum and aggregation benefits in urban areas. Almost nobody really wants to live in London because of the excruciating costs (unless you are young and just want to experience the life there for a couple of years, as I did when I moved there), but companies still keep setting up there despite the costs. All logic suggests that numerous companies based in London should move with their staff to, say, Liverpool or Newcastle or Glasgow because of the potential savings. But they don’t, and this has to be related to the business benefits of being in the centre of the action.

Not necessarily. It could simply be myopia, groupthink, and unwillingness to move for the same basic reasons that the hinterlands don’t want to move to “the center of the action”. The stock market, allegedly the most efficient market, is routinely prone to behavior which, in hindsight, was colossally stupid.

The corporate mind is sometimes blind to “potential savings” if it means a change in lifestyle, mental frame of reference and so on.

I saw my son playing a game called slither.io

In the game, you are a worm/snake-like creature, and you consume energy dots, or kill others to consume their energy. There is no cooperation, the more greedy and selfish one is, the more one succeeds. Eat all the dots you can, kill the smaller players without remorse, get as much for yourself as you can.

Metaphor?

The easiest way to combat regional inequality is a universal basic income.

http://www.interfluidity.com/v2/6674.html

Start a national dividend now!

a country can’t have a universal income without secure border control and ending jus soli citizenship. not trolling you. and probably not be a popular opinion here.

i’m sympathetic but just being realistic.

The other easy way is to directly employ people in those areas. In many ways, this is regional economic policy in the US, as military bases are established in poor areas for precisely this reason, and in the UK during the Blair years regional economic policy was largely replaced by an unstated policy of building up public sector employment in poorer areas.

Guaranteed employment would be more valuable a la WPA as it allows for someone to maintain or develop skills.

The problem I see with a universal basic income is that the extra cash will be rapidly extracted by increases in the basic cost of living. The mopes will be no better off in real terms, but businesses will have increased cash flow.

An example of this pattern: in Australia: right wing prime minister Howard introduced a $7,000 grant for first home buyers. Prices of ‘affordable’ houses at the bottom end of the market immediately rose by $7,000 (or more).

A jobs guarantee is a much better option. If there are plenty of government funded jobs at a modest living wage, kleptocrats are much less likely to have applicants for s*#t jobs (zero hours contracts, low pay, intensive performance monitoring, four hour shifts, defective ancillary benefits).

I know people on this site like the idea of a employer of last resort, but seriously, PARTICULARLY for regional issues, it is impractical. It requires overhead and has no way to match jobs to people’s individual skills and abilities (it would be much easier to implement in big cities). It also doesn’t liberate people to the extent that a basic income (essentially it is an art of regimentation). As for the cash being extracted by increases in prices I am not talking about housing subsidies (which I absolutely hate as an idea). The beauty of a universal basic income is that it will allow some people to live where they can afford to live, not where they can find a job. That both eases the housing crisis in some cities and I believe to some extent will result in the jobs following the people (partly because there will be more money in the communities and party because employers will move there). I think your simple responses to this are incorrect. But we won’t know until it is tried properly on a large scale. Arguing against even trying it (when nothing else is working) seems to me to be a form of willful ignorance.

A “jobs guarantee” doesn’t necessarily involve a single “employer of last resort”. In remote communities the local town already has the employment infrastructure in place, but often insufficient funds for all of the labour intensive maintenance that could be done.

My point about the benefits of UBI being sucked up by rentiers and salami slicers stands.

The problem with UBI is either:

1. Make it big enough for someone to live off independently in which case a significant number of people will exit the workforce, because while people like work they don’t like crappy jobs at McDonalds. This might make places like McDonalds have to raise their pay and prices to pay for it.Having even a few percent of the workforce dropout all at once could crash the economy. And I don’t know how you think a country that came up with welfare queens is going to do anything but stigmatize those people who rely on UBI.

2. Make it too small to live off of, Then if people still have to work they have no leverage at work and their bosses will pay them as little as possible because they know their staff won’t starve. Which is exactly what happened with the closest thing to an UBI ever tried:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speenhamland_system

Compare that to the limited JG Argentina did which was very popular untill a concervative government rolled it back because they didn’t like that so many women were in it. They rolled it back by offering a higher payment to people to just stay home. Many of them took the higher payment and just kept working for free because of the social bonds they made and that they felt like they were doing something good.

Here is a good paper on the problems with unemployment.

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_895.pdf

You need to learn to think more marginally. What almost certainly will happen is that some people will chose not to work in the formal sector (many will be carers of some sort or another), some people will chose to start businesses that they otherwise would not of, some people will chose to work part-time and all people will have a greater ability to say stuff it to exploitation and employers will up their game.

The ideal level of the universal basic income, will let people survive but not anywhere and anyhow (they may have to live communally in some places to survive). But how much will allow people to survive is not something will be the same everywhere and for everybody. But the point is, people will make a positive decision to work, not a negative decision. (P.S. There is absolutely no reason to believe everything will collapse if fewer people work voluntarily – you are forgetting that in the 50s only a minority of women worked and the dependency was also high then, because there were more children.)

I’m actually in favor of it being phased in, at first as a replacement for means tested benefits and tax deductions.

I’ve said before that I don’t think the Speenhamland_system is relevant because it wasn’t universal. It ended up being more like a guaranteed minimum income which I think is a bad idea and would almost certainly be gamed by employers.

From the Wikipedia entry on Speenhamland:

“The authorities at Speenhamland approved a means-tested sliding-scale of wage supplements in order to mitigate the worst effects of rural poverty. ”

The strength of UBI is exactly that it is NOT means tested (and it is also not regionally bound).

I also happen to think that a UBI (or better called a national dividend) would help with the tricky issue as well. Immigrants would not be immediately eligible (they would have to have residence status for a given period or even apply for citizenship first) for a UBI although they may get a tax deduction reflecting that it is not available to them, and so immigrants would need some to invest resources in order to migrate. This may result in a “market-based” solution to immigration control that would simplify border controls.

Economists are amazing, and I do not mean that in a complimentary way. Even this guy, seemingly decent enough, comes up with this head-banger:

>may be unlikely to relocate because of emotional attachment to the place

No. They probably are 1/3 of the way thru a mortgage on that place and there are no buyers in sight. So now what? Just hand the keys to the bank? Of course you vote for the Trumpian candidate, you don’t need racism to do that, you need some hope that you will be able to hang on to the biggest investment of your life.

according to surveys, the majority of Americans even can’t afford an emergency car repair.

can you imagine finding 1 – 2 months of rent for a security deposit + moving expenses to move across the country?

It is also possible that there are family reasons that could make moving more difficult. There may be aging parents that the potential movers are taking care of. Or, the potential movers may have children that the parents are watching during the day at no cost. Day care in the thriving cities is likely to expensive and inconvenient.

Dubbing it “emotional attachment” is condescending, but the importance of social bond as related to the region should not be dismissed. The social structure and institutions of your area are vital to your existence, even if they don’t show up on a balance sheet. Social detachment can be just as damaging to a populace as economic instability.

These people (economists) always say move to where the jobs are as if there are no costs involved. As if one’s an unmarried 20 something in a month to month rental and can just up and go. I could have gone to the SE US for a significant promotion and better paying job rather than choose unemployment, but outside of paying for the moving company there was no other compensation. So I was going to eat the selling costs of the house, my wife who works would now be unemployed, and given her line of work, her job prospects would be diminished where we were going compared to the NW.

And that doesn’t count that our parents, getting elderly were here who need us around. Do we move them? More costs. And the social cost of upending teenage children from school. But it’s so simple when it’s just a graph to these economists, or neoliberal apologists.

So instead I chose unemployment, and then a lower paying job which after a decade is comparable to what I would have started with. And I’m lucky as we had enough savings that we could have moved.

Where do these economists propose to put all of the people that are supposed to move? Most of the “vibrant cities” are extremely expensive with long commutes from affordable housing. I live in Upstate NY. As a professional, I am doing quite well as the cost of living is a fraction of what I would be spending in a major city. My one-way commute is 17 miles and about 25 minutes and rarely varies. I know what my peers in the major cities make and it is not much more than what I make, so I don’t know how they cover their extra costs. Right now we are trying to figure out if we retire at 62 or 65 time frame, both of which are likely to be comfortably very doable.

The median household income in our area can afford to buy a decent house in a good school district close to work. I think something is out of balance in our system where we are trying to pack everybody into just a few places and trying to write off the rest. In reality, there are a lot of very cool services and industries in our area, so clearly it is possible to do business here despite the propaganda.

I live in rural Michigan and work for the US Census Bureau (ACS). I see the “left behind” everyday. Most are living on between 18K and 30K, working full-time. Most have terrible insurance or none at all. Many homes are in dire need of repair; not new granite countertops, I am talking roofs and foundations. There is a generation divide with the older workers, 50+ and retired having at least a modest pension from their past jobs to augment their 15K Social Security. The young will see none of this. Also the “olds” own and the “youngs” rent.

This is an affordable buyers market. You can buy a home for 50k and if you do your homework it will not need 10k of repairs. People like living here, no traffic congestion, lots of lake, river, and forest recreational opportunity. Your kids can afford to buy in the area so you can see your grandkids, nephews, nieces more than once a year. They do not want to move to Chicago or Ann Arbor, and could never afford the housing costs.

They voted Bernie in the primary, Trump in the election.

Rural “high speed internetification” would bring people back. I already see CA and CO retirees fleeing the unaffordable housing situations in those states and appearing in Michigan. Especially on lakes and classic Victorian homes in the small towns. They sell their overvalued home in CA or CO and buy a place here for cash. They have 150K equity and can buy the cream of housing here. Many are working remotely and complain about the crap internet.

These are people who are solid working class and ripe for the picking for a Corbyn type Democrat. Of course no such character will ever see the light of day if the DNC can help it.

If we don’t get our Bernie in 2020, we may vote for Trump more and harder than ever.

Perhaps the “Clinton voters” should be reading the “Trump voters” as saying the following to the “Clinton voters” . . . . You have not yet begun to pay for what you did to us and what you did to our country. But you will. You will pay. We will make you pay.”

From FDR’s second inaugural address:

I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished. … The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.

– January 20, 1937

***

From Hillary’s fundraiser in NYC, 2016:

…We are living in a volatile political environment. You know, to just be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump’s supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables. Right?

… Now, some of those folks — they are irredeemable, but thankfully they are not America. But the other basket — and I know this because I see friends from all over America here — I see friends from Florida and Georgia and South Carolina and Texas — as well as, you know, New York and California — but that other basket of people are people who feel that the government has let them down, the economy has let them down, nobody cares about them, nobody worries about what happens to their lives and their futures, and they’re just desperate for change. It doesn’t really even matter where it comes from. They don’t buy everything he says, but he seems to hold out some hope that their lives will be different. They won’t wake up and see their jobs disappear, lose a kid to heroine, feel like they’re in a dead-end. Those are people we have to understand and empathize with as well. ”

The old Dem party talked about concrete material benefits for ordinary people. The new Dem party talks about tea and sympathy for ordinary people. Sympathy doesn’t pay the rent.

well everyone will kind of pay, including those who will be made even worse off under Trump (well with even more extreme plutocrats in power people will be made even worse off).

Which “Clinton voters” did what to the country that “Republican voters” haven’t also done, by electing politicians who serve the interests of the elites?

Also, what has been “done to the country” in areas of former industry/family farms/local businesses that hasn’t been done in cities and suburbs increasingly everywhere (closed businesses, abandoned residential property, declining/non-existent public services, failing infrastructure, privatization of the commons, gentrification, homelessness)?

Defining the work that needs to be done locally and regionally; defining how that work should be funded and the benefits distributed; and not giving facile responses like expecting people to get training or relocate are approaches that should be universally applicable. The 99% shouldn’t be imagining that making each other “pay” is going to get them anywhere.

(I don’t mean this as questions specifically to you, just started out from your statement that I maybe misunderstood, and expanding on a general reaction to the piece. After a lifetime of trying to think as a class-oriented lefty, I’m finally a little disgusted with the the heartland populists, and their failure to assimilate into the diverse fabric of US life and culture, to blame the Other and not the oligarchs.)

That’s easy. The Democratic Establishment deregulated Wall Street, signed many of the trade agreements that helped decimate manufacturing jobs, and frankly could care less about the common citizen.

The Clinton base, by choosing Clinton over Sanders proved that they do not have any sense of noblesse oblige for their fellow citizens. Clinton supporters certainly don’t have any issues with her ties to Wall Street or the neoconservatives.

No dispute with that critique of Clinton Democrats. But the Republican establishment doesn’t care about them either. State and local Republican governments, and Republican national politicians, sell them out constantly.

Californians don’t need to go far in being equity refugees fleeing the Big Smokes, you can buy the same house for 1/3rd of what it costs in LA/SD and 1/4 the price of an abode in SF, but it isn’t as if there aren’t 40 homes on the market as I type, so they aren’t beating the doors down in buying them here. That said, there is really no potential for making money, but if you had $500-750k left over from selling your paid off house in metropolis and are say 63 years old, you’d be pretty much set, along with SS payments coming in.

One thing I enjoy here, is the clothing you wear or the car you drive, means absolutely nothing in the scheme of things, nobody really puts any effort into keeping up with the Joneses-real or imagined, very refreshing.

I am one of those very same Colorado residents you mention. You’ve piqued my interest!

I have family in northeast Oklahoma, and it is very similar in terms of demographics/salaries. There is a strong rural coop in the area originally for power but it brought in high speed internet (gigabit) a while back. Every time I visit I get more and more interested in staying.

Not to be too snarky about the whole “left behind” meme…. but…. left behind by whom? to move where?

Those “left behind” areas correspond pretty well to the manufacturing zones (and jobs and skills) now outsourced to China and elsewhere by big business, with govt’s and both parties’ blessings (see tax policies).

Besides the points you make — how durable are the jobs “country-mice” will find if they move? The Neoliberal concept of moving to fill jobs as they jump around the country — before those jobs find an exit to places far far away — looks more and more like the mobility of “Grapes of Wrath” fruit pickers. And of course if a job can’t be sent away the mobile workforce can always be replaced by “illegal” immigrants or H1-B contractors — if wages get too high. It all kinda chops the benefits of moving off right above the knees.

I found this article unintentionally comical: an illustrious academic revealing, with great fanfare, what is patently obvious to everyone else: (a) certain geographical regions are in profound economic decline as local industry flees to low wage countries, and (b) for some reason the people in these areas are not complying with economic theories telling them they should move somewhere else!

Indeed! “We” have been blind!

The bland assumption that people in economic distress will pull up stakes and move somewhere else seems naive. For starters, it costs many thousands of dollars to actually move: lost work time, transporting one’s property, deposit and first/last month’s rent on new dwelling, utility hookups, and so on can add up to a big number, literally beyond the reach of many people. Secondly, living costs are likely to be much higher in “agglomerated” areas, and may be impossibly high for people who are already on the economic edge. Most importantly, leaving behind a support network of family and friends, who can normally be counted on to help out in emergencies, in favor of a place where you don’t know anyone, can be a dangerous and scary sounding move, especially in places where formal social supports are unreliable, minimal or nonexistent, as in most neoliberal areas. It’s one thing for a Cambridge professor to move to Oxford to take a new position; it’s another for a home health aide or Walmart employee to move from a small town to London or New York.

This is a common elite and coordinator-class meme, that providing benefits to people makes them “dependent.” It’s true that people, even elites, have an unhealthy dependency on eating and having a roof over their heads. I’m not sure what the point of this concern is: that providing things to the population is verboten unless they are busily creating wealth for rentiers? Just providing stuff for people to live and perhaps have some quality of life is a complete waste, and is to be avoided?

I share this dude’s inability to perceive a clear solution to the problem of deindustrializing regions. But I’m glad to have his excellent brain working on the problem!

I think you raise an important point in objecting so well to the naive assumption that people will behave according to the models and forsake the lands of our birth for a miserable life in an overcrowded city for a pittance of a wage that’s not even enough to feed a dog.

You, politicians and mainstream academics, have caused a lot of pain. You could at least say sorry.

I’m sure the author is well meaning. But here’s the thing. Your (collective) ideas have been causing us a great deal of pain, anguish, and untimely deaths for quite some time. Your reforms failed to notice the blindingly obvious, human fact that our lands, and the lives made from them, are important to us, making things worse.

How many more chops at the body politic are you hacks going to take?

Why on earth should we listen to you, politicians and mainstream academics, any more?

We’re only lagging behind areas on economic steroids. There’s no way they’re sustainable.

How many times does their model get to fail before we can call it dead?

Disembodied, denatured, uprooted — no wonder they fantasize about robots.

Is giving the finger to agglomeration an option? Because I’m sure feeling like it right now.

What if it’s the agglomeration, and there’s no ameliorating it?

What if we don’t want you and your gd agglomerators “maximising” our “development potential”? What we need are optimal and sustainable ways of living with respect to the land, the air, the water.

We’re sick to death and dying in droves from “maximizing development potential.” What makes “dynamic areas” dynamic? Their long-term, as in centuries, sustainability? Or is it just another boom, and we’ll be discarded in the bust, just like every time before?

“You will be agglomerated. Resistance is futile. TINA.”

No alternative? Sure there is.

[Cyberman voice:] “6th mass extinction in progress.”

As a couple of commenters have already pointed out, the author neglects to factor in the importance of social ties in economic security. Elites depend upon their Rolodexes to get plum internships for their kids, get tips on investments, find the best housekeepers and gardeners. Likewise, lower income people depend upon family connections in help finding jobs, child care, housing etc.

My SO’s family is from southern Mississippi and many of them live in the panhandle of Florida. They’re mostly low- to middle-middle class, and while a few escape north or west, for the most part they wouldn’t dream of leaving the area. Parent, siblings, cousins, grandparents and grandkids–all the extended family that supposedly doesn’t exist in America any more–are THE social safety net. To leave there means to leave a strong and reliable support system. Even if the jobs are mostly crap, the cost of living is nowhere near what it is in the big cities, and if things go sour there are folks to help you out.

What’s absurd is the assumption that economic development must be centralized. A century ago, a factory was often sited close to raw materials or shipping, but also becasue that’s where the people lived who wanted to open a factory. Why do all our shoes need to be made in Bangladesh? Why did Carrier leave Indiana? Simply because someone can make more money that way.

So let’s not pretend that there’s some invisible, unstoppable force that directs all the wealth towards major elite cities: it is a system of deliberate centralization, by individuals who control capital, in order to concentrate wealth. The left-behinds are on their own, and the sooner we realize that the better. Communities will have to find ways to build wealth locally and keep that money local. StrongTowns.org has much to say about this idea.

I’ve linked to this blog a couple of times recently, but this post is particularly pertinent to the topic:

My Reno Epiphany

I went to the website you linked and forgot to block Javascript. Something about that site brought my old computer and old old Firefox browser to its knees. After something did manage to load I saw a comment from Wisdom Seeker there — so the problem may be a problem peculiar to my system. But some script was hogging my CPU and I couldn’t shut the site down even after I pulled the Internet cable out. In the end I had to re-boot. All the photos at the top of the site are pretty but they took forever to load.

Yes, that is a good point and well summarized. It’s more than just emotional attachment that keeps people from leaving. I suspect it’s very common for much of the value that people have to offer in the labor market to be tied to a specific place (most notably established networks and support systems). Talk to any expat and ask them what it was like starting over in a new country.

I do think that the recommendation (regional development plans) is reasonable, provided it’s done in a way that doesn’t imply central planning or presume that national governments know better than local ones. The question will be the same – what will it take to revitalize this region economically? – but there may be different answers for every region, and getting the right one for the situation will require deep and detailed knowledge of the local community strengths and values. So what’s needed is really a plan for how everyone can have a plan, so to speak.

I would suggest picking a handful of trial communities, building a team of regional development experts, community and business leaders, and people with local knowledge, and letting them figure out what works. If common themes emerge then they could be translated into a blueprint to streamline the process and help local communities develop plans of their own. Government could then conduct periodic checks and reviews to confirm how things were going, say every year, every 5 years etc. (Is there a plan? How is its success or failure being measured? Is it working? Does it need to change? etc.)

This kind of thing is not at all uncommon in western countries that aren’t the USA. Building permits in New Zealand work this way, for example – there are a patchwork of district plans, maintained and updated by local councils, that are used for assessing compliance. Sometimes they work well, sometimes not so well, and sometimes they create other issues or side effects, but by and large they are at least somewhat successful in achieving their objective. So it could be done, but a necessary prerequisite is to agree that it’s worth doing, which is not the position of either major US political party at present.

The mobility of labor in the U.S. has been tauted as a big economic advantage for a long time. As you point out and as pointed out by many of the commenters the costs for moving — social and economic are high and I believe they have increased substantially over the years — at least they have in the U.S. And the payoffs for moving have gone steadily down. Many of the jobs only lasted for a few years before they moved on or turned to crap as roving downturns hit one locale or another.

I recall the big move of workers from Detroit down to Dallas-Fort Worth in the 1980’s. The boom in the early 1980s turned around in a couple of years as ranching, oil, and aerospace all slowed down together. I heard that a lot of the Detroit people ended up heading back to Detroit. The Seattle area is famous for its ups and downs dating back to the space race days which is as far back as I remember. During those same space race days I remember entire neighborhoods of San Diego turned into nearly empty ghost towns after the big layoffs. And as they say — once burned twice shy. The American people have been pushed to make what ended up as temporary moves a few too many times.

However I think I would re-frame your observation “that economic development must be centralized”. I think centralization is less the key than the notion that economies of scale always argue bigger is better. How many economies of scale result from monopoly rents rather than any inherent gain in efficiency? One other thought related to the centralization of economic development. There are advantages to aggregating related industries together in one place for manufacturing processes. I think jobs move overseas to take advantage of cheap labor and as a means to exert control over local labor. The moves usually decentralize the location of capital and extend supply chains. The efficiency gains and even the cost savings are putative at best.

The issue here is that the elite and by that I am referring to not just the really rich, but also the top 1p percentage of the income earners, look down on the problems that the citizens in such declining areas occupy with deep disdain.

Deplorable is the term that Clinton used, but it is how the well off see those who are in trouble. You could tell because of the way that Clinton supporters continue to see Trump and even Sanders supporters.

Worse, the economic problems were caused by the rich to begin with. The struggling population isn’t wrong to blame the very wealthy in the big cities. A lot of our problems came be blamed rightfully on Wall Street, the robber barons in Silicon Valley, our corporate senior management, and frankly the upper middle class as a whole. Inequality is rising admit they are to blame. Other issues such as outsourcing jobs to nations where the people are paid little are rightfully blamed on the corporate elite.

The tragedy is that Bernie Sanders would have tried to actually make it better. Trump has become a predictably obvious, through still infuriating sellout despite a populist campaign. That’s no doubt why the Establishment stopped him.

Oh and finally, it shows how ridiculous the economics profession is. They seem to think that externalities don’t exist and that moving is free. As discussed elsewhere it is a sad reflection of the state of the profession and a clear indication that it has been co-opted by the rich.

If the book Fire & Fury is even 50% close to the truth, Trump really has no idea what he is doing. None. Zip. Zero. Nada. A Comi-Tragedy of epic proportions.

Trump is actually the quintessential example of why running a business has nothing to do with running a government.

If the book Fire & Fury is even 50% close to the truth

I skimmed through a couple of chapters and I highly doubt that this is the case. The book seemed to me to be an attempt at character assassination disguised as an insider’s take. The author has an agenda and as such, has less than zero credibility. FWIW he recently managed to get himself kicked off Morning Joe while the show was live and he was sitting at the desk with Joe and Mika, which was quite amusing imo.

Sigh … autocorrect, but you get the gist of what I am saying here.

The issue is that the places that don’t matter once did have middle class opportunities … and now they have few options available, plus are looked down upon by the more prosperous classes. Elections like this are the only way to signal that all is not well.

Another great article demonstrating that economics is not a science, that its so-called experts do not even begin to understand the subject they profess.

Two extra dimensions not fully touched upon above:

(1) The rise of dual-income households makes relocating at least doubly-difficult compared to prior generations.

(2) The “places that don’t matter” typically either eschewed or were left out of the massive financial inflation of the past 2-3 decades. They may have been “left behind” simply because they didn’t like the taste of the punch the central bankers and governing elites served out to their crony-capitalist friends. That choice doesn’t necessarily make them economically depressed (although having their high-quality jobs exported would not help). But by avoiding the great inflation, these regions have vastly lower cost of living than in the “centers of action”. For metrics that neglect cost-of-living factors, these places might appear poor, but in fact the true standard of living is no worse than in the large impersonal cities. Put another way, this conceit that some places are “better” than others may be yet another case of delusional elite groupthink, a prejudiced mindset which the local residents rightfully disdain.

Not a bad piece, but a whole lot of ‘duh!’ stuff in there, especially w.r.to the as-ever-completely-clueless-because-paid-to-be-so “expectations of economists”. For example the ‘expectations’ regarding interpersonal wealth inequality – these folks apparently never heard the term “class warfare” in their elite ivory towers, it would seem. And why is it reasonable for a Deplorable to resent a wealthy person simply based on their contrasting levels of affluence, especially if the latter’s wealth is seen as being not criminally gained? Aye, there’s the rub, but again the criminogenic cesspool that is the modern elites and the governments which serve them gets little mention here.

Economists argue that “subsidising poor or unproductive places is an imperfect way of transferring resources to poor people” – Massively subsidizing – to the tune of whole-GDP-level bailout monies – and de facto immunizing them for their crimes, on the other hand, is absolutely necessary to ‘ensure our economic future’, right? Just as is the restructuring of modern “post-industrial” – a term bandied about as if it described some inevitable state of natural economic evolution, rather than the result of decades of deliberate policy choices – economies into a series of ever-larger asset-price bubbles which raise prices beyond livable not just for the service-economy toilers in the urban centers of affluence, but also for those left behind in the hinterlands, and each cycling of which transfers ever more of the economic pie to the financial parasites and the rentier class.

Word. Well said. It’s as if recent history hasn’t happened. As if so many, being so wrong, for so long, never happened. Not so much as an “oops, my bad.”

Like we’re not supposed to notice the $29 TRILLION spent on the very gd perps who stole our houses and crashed the economy.

I think I get it now. They developed us off the land and into jobs, then developed the jobs out of reach, then we were supposed to develop ourselves into “dynamic” areas, leaving all that real estate dirt cheap for their gentrified “getaways,” where they can get away from the world they developed. Except when it comes time to pay the bill for climate change, that is, at which point, “Humanity did it.”

If only all us stakeholders would maximise our development potential, everything would be right as rain. Acid rain in a climate of catastrophic change, that is.

Gah – “Massively subsidizing – to the tune…” should read “Massively subsidizing the crooked bank cartels – to the tune…”

You want to know why people in places that have been abandoned by their governments act out their rage at elections? It is because of what they hear and are told. James Carville (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Carville), who some may have heard of here, said once on the destruction of America:

“Who cares? Sometimes you need rebirth” (The Colbert Report, 9/20/06).

Oh please. Don’t be so monocausal. Yes, what we hear does inform us. We also have things of our own to say, and reasons of our own for saying them. We’re not just a bunch of stupid cattle who need bossing around.

May I suggest tempering that absolute with a bit of fresh ground qualifiers?

BTW, is that Colbert show still a thing? Who watches him anymore, anyway? He used to be incisive. Now he’s just insipid.

Uhh, I barely know what the Colbert show is so I am only quoting the source here and wouldn’t know it from a block of cement. I thought that his comment though completely in line with Hillary’s deplorable comment, Obama’s clingers comment and Romney’s 47 percent comment.

As I have said before, one line can be an anecdote but several can constitute a pattern. Also, I never talked about a bunch of cattle here. What I am saying is that you have to understand what you are dealing with before you actually deal with it. This line, for example, shows you what a top democrat thinks of America.

I live in Northern California, in Lake County. You can find us on a map, by looking between Santa Rosa and Sacramento – we are basically north of both of those cities, but east of SR, and West of Sac. So we are the tip of a triangle if you plot out all three places.

Officially we rank at 18% unemployment. but I will say this: every year when the harvest is in, people are animated and you can tell there is prosperity. The nation’s Number One Crop is semi legal here. And for those who grow it legally (which has certain bureaucratic challenges and certain taxation disincentives) and for those who grow it on the sly, there is much satisfaction in knowing we are restoring prosperity to this part of the world.

Maybe Liverpool needs to “Think Green.” If “Thinking Green” involves grow lights or hydroponics to help them achieve the goal, there are plenty of stores here in Lake County that would be happy to ship them the needed items.

In sociology they teach small things happen in small places.

Port cities live forever.

There are large ports & small ports, but the lesson is be a port

to be.

I live in rural part of Shenandoah Valley in Virginia.. The county I am in has three colleges which keep it culturally richer than most rural areas. There are enough rich living here (or have their 10,ooo sq ft. 2nd? 3rd? homes on the hilltops looking down so that it isn’t a throwaway zone. The factories stopped here from the unionized North on their march to Mexico – it made for a better living than dirt farming or raising cattle.. One town where many of the factories “were” was so democratic the governor (if a democrat) would come on Labor day for a speech even though it only has a population or 7ooo. Last year it voted for Trump. This town would have died except the Mormons bought the failing 2 year college that catered to rich girls who liked to ride. It also hocked itself to build a golf course thinking it could make it back on property it owned surrounding it. Then 2008 Property values have increased such that I could not afford to buy a house now – although the bank would lend me the money – I would be poor if I had to pay a mortgage. Jobs are a problem for the young. It is still a great place to raise kids if you have steady work. The counties between us and West Virginia or south of us – not so much. As for West Virginia – there are a few counties still in the good times but mostly a Chris Hedges “throwaway zone”. Except for jobs at the motel next to the interstate or a convenience store – its the military to get away if you’re not an exceptional scholar.- aside from the small number of teachers or deputies and necessary maintenance types of work like linesmen, carpenters and plumbers etc…