By Nick Cunningham, a freelance writer on oil and gas, renewable energy, climate change, energy policy and geopolitics. He is based in Pittsburgh, PA. Originally published at OilPrice

In a worrying development, global CO2 emissions from energy jumped by 1.4 percent in 2017, the first increase in three years.

The trend indicates that global efforts to reduce emissions are “insufficient,” according to a new report from the International Energy Agency. Total energy-related emissions jumped by 1.4 percent to 32.5 gigatonnes (Gt), the equivalent of 170 million additional cars. The prior three years, energy-related emissions were flat, raising hopes that the curve might bend down.

Still, emissions did not rise everywhere. Notably, the U.S., Mexico, Japan and the UK saw emissions decline. In fact, the U.S. posted the largest single-country decline in emissions in 2017, dropping 25 megatonnes (Mt). It was the third consecutive year of declining emissions, which may surprise some given the Trump administration’s efforts – he withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement, he has actively promoted coal, oil and gas production, and his EPA has done all it can to roll back Obama-era climate policies.

Despite the trend in federal policy, the transition to cleaner energy is, at this point, driven more so by market forces than by the whims of Washington. Renewable energy outcompetes coal and even natural gas in many places.

Indeed, the IEA noted that in years past, the cut in U.S. CO2 emissions was largely the result of utilities shutting down dirty coal plants and switching over to natural gas. However, in 2017, the 0.5 percent drop in U.S. energy-related emissions was the result of more renewable energy, rather than natural gas. A decline in electricity demand also chipped in. The proportion of electricity coming from renewables jumped to 17 percent in 2017, while nuclear power accounts for 20 percent.

Similar trends played out in the UK and Mexico, where coal also took a hit. In Japan, some nuclear power came back, helping it to displace imported oil, coal and gas.

But strong economic growth (GDP jumped by 3.7 percent) and low prices for oil and gas led to a lot more consumption. Meanwhile, the IEA said that weaker energy efficiency efforts also contributed to the uptick in emissions.

Related: Colombia’s Fracking Dilemma

“Global emissions need to peak soon and decline steeply to 2020; this decline will now need to be even greater given the increase in emissions in 2017,” the IEA said in its report.

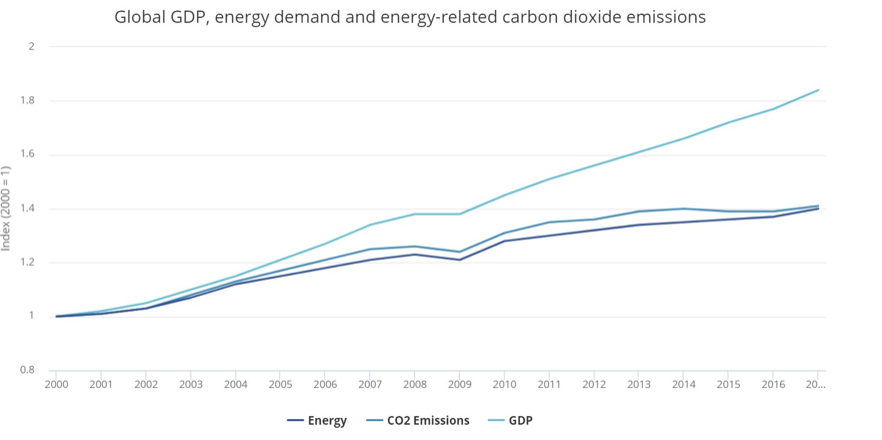

One hopeful trend is the semi-decoupling of energy consumption and GDP. For decades, economic growth grew in lockstep with energy consumption. The two started to diverge in the mid-2000s as the global economy continued to expand but sky-high oil prices started to force some efficiency measures. Since then, the global economy has grown much faster than energy consumption.

China, for instance, still added CO2 emissions in 2017, but at a significantly lower rate than its GDP growth might suggest. The Chinese economy expanded by 7 percent, but CO2 emissions only rose by 1.7 percent. The decoupling is in part due to the ongoing coal-to-gas switch, an effort to clean up urban air pollution. It wasn’t so long ago that news stories talked about China building a new coal plant every week, but China’s coal consumption actually peaked back in 2013.

China still has some new coal plants coming online, but those have been in the works for some time. The Chinese government put strict limits on new coal plant construction beginning in 2016, while forcing older and dirtier ones to shut down. China still has a lot of coal plants on the drawing board, but has effectively shelved plans on a whopping 444 GW of coal-fired capacity, according to a new report from the Sierra Club, Greenpeace and Coalswarm.

On the other hand, so-called “energy intensity” – or the amount of energy consumed per unit of economic output – declined at a slower rate than in the past. In 2017, the energy intensity of the global economy fell by 1.6 percent, a less impressive figure compared to the 2 percent improvement in 2016.

Related: Oil Traders, Supermajors Diverge On Demand Forecasts

China and India were a big reason why global energy consumption jumped by 2.1 percent in 2017, a rate twice as large as the year before. Those two countries accounted for 40 percent of the global increase in energy demand.

The bottom line is that energy consumption is still rising, despite the larger presence of renewable energy and the nascent EV industry. It is no wonder that the oil majors do not see peak oil demand as an imminent problem.

“The significant growth in global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions in 2017 tells us that current efforts to combat climate change are far from sufficient,” said Fatih Birol, IEA executive director. “We are far from being in line with the climate targets set in Paris,” he added.

Were the climate targets set in Paris actual goals or were they aspirational goals? From what I read at the time, they were not enough, not even by half. I am afraid that far too much of climate change has been backed in and it will take centuries for it to play out. I intend to re-read John Wyndham’s 1953 book “The Kraken Wakes” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kraken_Wakes) this weekend as it depicts a world with rising sea levels. True, it was caused by aliens in this novel but the effect is the same.

India: “I’m asking the developed work to vacate the carbon space so that we can park our development,”

Excluding developing countries from compliance was always the rotten core.

Actually, the rotten core was and is us. Nice try, though.

It cannot take centuries

Cannot? I hope not, but …

Fifteen years ago, the Caldeira Lab (Carnegie Department of Global Ecology)

There is a huge gap between the required emission cuts and the “pledged” emission cuts required for 2C: Climate Action Tracker. Cuts are voluntary and there is no enforcement mechanism.

Up to this point, Paris has been pretty meaningless. The big news will be when emissions drop 5 or more percent in a year. At current emissions levels, flat emissions locks us over 2C before 2040.

Paris has been completely meaningless…despite Trump’s pullout, “the U.S. posted the largest single-country decline in emissions in 2017”

That doesn’t make Paris meaningless though. The accord is meant to spur signatories to actively invest in the cleaner technologies, right? If this administration weren’t such reactionaries, we would be adding to the gains.

In Spain oil and oil liquids consumption has increased with economic “recovery” during 2015 and 2016. A sligth increase was recorded in 2017 (0,45%). Spain signed COP21 but the government does next to nothing to curb emissions. Is Trump a bad guy because he promotes fossil fuels and is Rajoy good because he is compromised? Maybe but if one looks at the results it seems both are equally incompetent.

I find the numbers for China dubious. For decades, China’s energy consumption has risen in lockstep with its GDP growth (e.g.https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=8070). Furthermore, as the great bulk, around 75% of China’s electricity generation was provided by coal and other fossil fuels, and as transportation, the second biggest contributor to emissions, was virtually entirely fueled by fossil fuels, China’s CO2 emissions grew in lockstep with its GDP. Yet now we’re told that suddenly in 2017, China’s GDP grew at 7% but its emissions only grew by just 1.7%. How did this miracle of de-coupling happen? The IEA attributes this result mainly to a partial shifting from coal to gas last year. But while scientists can accurately sample and count the parts per million of CO2 and other GHG gases, such as methane, in the atmosphere, counting the emissions of particular countries is mostly guesswork because these cannot be directly measured (there being no practical way to measure the emissions of billions of tailpipes and myriad other sources of emissions). They can only be inferred from data about production and consumption of fossil fuels. In China’s case this raises two questions: First, is the government accurately reporting energy production sources? In 2015 it was reported that in fact the government regularly lied about these, underreporting coal consumption by around 17% (https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/04/world/asia/china-burns-much-more-coal-than-reported-complicating-climate-talks.html). Secondly, while it’s true that in theory combustion of natural gas releases fewer CO2 emissions than coal, numerous studies show that in practice there is so much methane leakage all along the production-consumption line from drilling to piping to storage to filling stations that natural gas likely contributes as much if not more carbon emissions than coal. Yet the IEA appears to take the optimistic theoretical assumption that gas produces lower gas emissions than coal in their statement that the partial shift to gas ipso facto reduces global GHG emissions. But if this predictable leakage is not taken into account by the IEA, then their report could be wide of the mark. Given what we know about China’s woeful industrial safety record I would be surprised if leakage in China were not at least as great as leakage in, say, Pennsylvania, in which case the estimates of China’s actual emissions are likely to be closer to its rate of GDP growth. But I’m not a scientist. Perhaps others could weigh in to enlighten me and clarify this for us.

A graphic to add to Nick’s article. Up to this point, the only thing that has really slowed down global carbon emissions are economic crises: CO2 vs GDP from the Global Carbon Project. While CO2 per unit of GDP has decreased, it has not decreased fast enough to really drop global emissions. More graphics from the Global Carbon Project here and the whole report is here.