Lambert here: For the world richest elite, the British peerage seems to be doing a p*iss-poor, Bertie Wooster-level job of noblesse oblige. I think I’ve plated this before, but:

By Paula Gobbi, CEPR Research Affiliate, and Marc Goñi, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, University of Vienna. Originally published at VoxEU.

Inheritance practices have long attracted the attention of economists. Adam Smith was scathing in his criticism of primogeniture and entailment of the land.1 He argued that these laws increased inequality, “making beggars” of all but the first-born (Smith 1776). Recent studies that suggest that wealth inequality and the incidence of inherited wealth are both rising have once more highlighted the impact of inheritance practices (Piketty 2011, Atkinson 2013, Saez and Zucman 2016).

The economic effects of any inheritance scheme depend on fertility choices (Stiglitz 1969, Atkinson and Harrison 1978). Most importantly, they depend on the production of an heir. Despite this, modern studies of inheritance ignore both the effects of inheritance rules on fertility choices in the extensive margin, and how fertility concerns may determine the type of inheritance used.

Our recent research finds new evidence of a two-way link between inheritance and fertility for the British peerage, the world’s richest elite.

The World’s Richest Elite

It is hard to exaggerate the riches of the 300 families in the peerage (Cannadine 1990).2 For example, while the average member of the top 1% in the US earns $1.3 million a year (Wolff 2012), peers earned $2.5 million (in 2008 US dollars) in the 19th century (Goñi 2018). Though in decline, the peerage remains rich: 68 peers were included in the 1,000 richest in Britain in 2000 (Cahill 2002).

The peerage was not pre-destined to be at the top of the distribution. Demographics were not on their side: around 1600, between 30% and 40% of married women in the peerage were childless. For the average commoner, the corresponding rate was only 10% (Figure 1). This threatened the survival of aristocratic lineages.

Figure 1 Childlessness rates, by marriage decade

Notes: * sample: married women whose father is a peer; ** sources: Wrigley et al (1997), Anderson (1998).

So, how did these aristocratic lineages survive?

As suggested by Adam Smith, inheritance practices helped British aristocrats to consolidate their wealth, and their position at the top of the distribution. This is only part of the picture. In a recent paper (Gobbi and Goñi 2018) we show that the inheritance practices of the aristocracy boosted fertility decisions in the extensive margin (in other words, having children or not). Inheritance rules contributed to the perpetuation of the British elite not only by preventing family estates to break, but also through changing fertility incentives.

An Inheritance Scheme that Boosts Fertility

From 1650 to 1882, inheritance in the British aristocracy was regulated by settlements. Settlements combined male primogeniture with a one-generation entail of the land. In the textbook case, the family head and the heir signed a settlement by which the heir committed to passing down the estate, unbroken, to the next generation (Habakkuk 1950). The social convention was strong. Few heirs refused to sign a settlement with their fathers (Stone and Stone 1984). Importantly, settlements were signed upon the heir’s marriage, as they also included provisions for the wife (Bonfield 1979).

Why would settlements affect fertility? When an individual was subject to a settlement, he could not break the family estate, sell it, or mortgage it. He may choose to have children, if he preferred the large, ‘untouched’ inheritance to go to his offspring. Otherwise a distant relative would have inherited the estates. For the settlement to change fertility incentives, however, the family head had to survive until his heir’s marriage. If he did not, the settlement was not signed, and the heir could have sold parts of the family estate.

To estimate the effect of settlements on fertility we used genealogical data collected by Hollingsworth (1964) from peerage records. These data do not state who signed a settlement. We can nevertheless identify families in which the father died after the heir’s wedding, and hence, in which a settlement was signed, and families in which the father died before wedding, and in which the heir would not have signed a settlement.

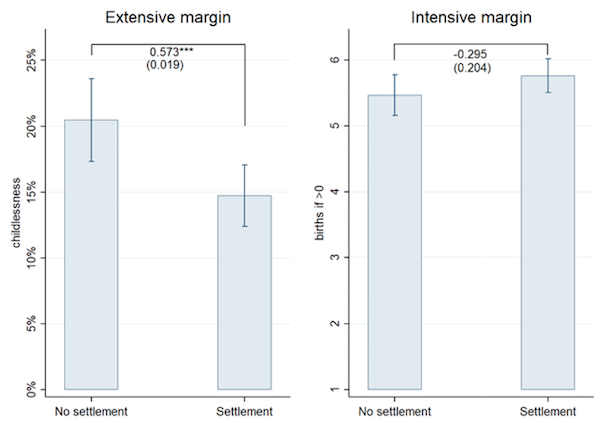

Figure 2 summarises the results. Families signing a settlement had significantly lower childlessness rates. The magnitude of the effect is larger when we control for variables that potentially affected childlessness, such as the age of the spouse at marriage, or the number of stillbirths. Our results are robust to including family fixed effects, which capture any genetic, cultural, religious, or socioeconomic predisposition towards childlessness. In contrast, we do not find an effect of settlements on the intensive margin of fertility (births conditional on having at least one child).

Figure 2 Effect of signing a settlement on the extensive and intensive margin of fertility for aristocrats

Note: We assume that a family signed a settlement (did not sign a settlement) if the father died after (before) his heir’s wedding.

It is possible that individuals may have chosennot to sign a settlement by delaying marriage until their father’s death. To address this, we exploit the birth order of the heir. Since families could not control the gender of their children, a male heir might not have been born until the second or third birth. In these families, the father is older, more likely to die before the heir’s wedding, and hence, exogenouslyless likely to sign a settlement.

Instrumenting settlements with the heir’s birth order, we find that signing a settlement increased the extensive margin of fertility by 83.5%, pushing childlessness rates close to the ‘natural’ rate of 2.4% (Tietze 1957). In other words, settlements contributed to the survival of noble family lineages.

Permanent Entails in Scotland

In Scotland, peers could use permanent entails (Habakkuk 1994), unlike in England. Because these entails did not have to be renewed every generation, it should not have mattered for fertility whether the father died before or after his heir’s wedding. Our estimates for Scottish peers are close to zero, and significantly different from our benchmark results. This strongly suggests that we have captured the causal effect of settlements, rather than confounding factors correlated with the father dying before or after his heir’s wedding.

Why Would an Heir Sign a Settlement?

A settlement restricts an heir’s powers to manage the family wealth, so to answer this we develop a simple model of inheritance and fertility. We relax the assumption of exponential discounting across generations, commonly used in bequest models (Barro 1974). Instead, we introduce dynastic preferences, so that individuals would value their children’s well-being similarly to that of the future generations. This type of discounting is appealing for two reasons:

- Dynastic preferences are well-suited for the aristocracy and other wealthy elites.

- Dynastic preferences rationalise inheritance schemes that restrict successors.

In the model, the family head prefers to use such a scheme to provide for his grandson. For the heir, signing a settlement – even if this restricts him in managing the estate – is a credible commitment to have children, which ensures that his father would pass down a larger share of the estate.

In sum, our model predicts that concerns over the production of an heir may shape inheritance rules – in particular, rules that restrict successors.

Lessons for Today

British peers were the wealthiest elite on earth. However, from 1650 to 1882 they did not freely dispose of their estates. On their marriage, they signed a settlement, renouncing to sell or mortgage parts of the family estate before passing it down. We find that such arrangements reduced the high rates of childlessness in the aristocracy, ensuring its survival.

Should we care about an elite who spent their time in debutanteballs and fox-hunting, and who lived “on money that were invested they hardly knew where?” (Orwell 1968). In light of the recent surge in inequality and the importance of inherited wealth, we argue that history can teach important lessons. We show that inheritance models treating fertility as exogenous can be misleading, because inheritance schemes affect fertility decisions which, in turn, can shape inheritance practices.

In addition, the study of settlements allows us to understand inheritance practices that restrict successors, which are increasingly popular. For example, trusts are likely the most popular inheritance scheme among the top 0.1% in the US (Wolff and Gittleman 2014).

Since Adam Smith, many have argued that inheritance schemes that restrict successors can perpetuate elite lineages. We suggest that they can so not only by consolidating wealth, but also through changing fertility incentives.

Endnotes

[1] Land entails are arrangements that restrict the successors capacity to break the family estate; i.e., sell parts of the land, mortgage it, etc.

[2] After 1900, the size of the peerage grew to 900 families.

Timely study, given the latest ‘royal’ birth. I remember reading a study a while back which pointed out that a small percentage of the British hereditary ‘aristocracy’ owned most of the land in England, Wales and Scotland.

The google confirmed my memory with numerous citations, but here’s one of my favorites, from The Socialist Worker:

I think that you forgot to include a link.

/https://socialistworker.co.uk/art/43221/Who+owns+Britain+How+the+rich+kept+hold+of+land

Sorry, I can’t always make the ‘link’ think work. Aging brain and all that.

where I live, the local economy and polity are dominated by maybe 20 old, old families…descendants of the folks who first came out here and stuck a flag in the ground and thereby claimed a bunch of land(usually several “sections”(=640 acres,iirc). The German Idealists of the Adelsverein were first(and made a treaty with the Comanche that is one of the handful of such agreements that has never been broken)…”Anglo-Americans” came later, just prior to the Civil War.

While the Germans seem to have been more prolific(having many kids), they also seem most likely to have hung on to their land, more or less intact, until today.(folks refer to “Loeffler Country” or “Grosse Country”, even on the scanner when there’s a fire…and I can’t think of an Anglo-American analog)

Those settlers were from Noble, or Near Noble families…so I’ve suspected(but do not know) that traditions of ideas like primogeniture may have played a part in their keeping it together.

A bigger thing might be the sober, long term outlook that they brought with them. The Anglo-Americans were (stereotypically) after fast riches…the Germans were after stability and building for the far future(grandkids, etc)—except for the most idealistic among them, who starved out after a few years(see: Latin Colonies of Central Texas; Bettina, Castell, etc).

Of course, for the last 20+ years, farming has withered, and cattle is a risky business…so many of these families are “land rich, cash poor”, but it’s rare enough to be noticed and talked about that one of them sells off a patch in order to pay property taxes and/or debt.

I’ll bet, as happens around here, that the “land poor” members of the families often sell to other, better off, members of the same family.

there’s one big German family who notably got into trouble in the last 20 years.thousands of acres on several adjoining ranches along the river(good ranching, bad farming country. they were late to take advantage of tourism(hunting/B&B/even eco)).

some sold to cousins, and some sold to Neuveau Riche(mostly oil money, it seems) from somewhere else…depending(as far as an outsider like me can tell) on how deep that particular branch was into the feud that is like a defining aspect of this particular family.

The differences between the AngloAmericans and the Germans(3rd-6th generation is who I know) has fascinated me since I learned the history of this place…and how those differences have influenced the political economy and social structure of today.

Especially that of the Germans…”Freethinkers”, anti-war, anti-rapine, anti-racist even anti-patriarchy(for the time)…they’ve had a large influence on this place, compared to even a few counties over.

I find your comments and observations interesting and wanted to kindly suggest a source which might help you in understanding (or at least in getting a difference view on) some of the differences between these Germans you mention and other peoples settled in your area. Namely, I wanted to suggest Baron von Haxthausen’s book “Studies on the interior of Russia”, written in the mid 1800s. This Baron was a contemporary of Alexis de Tocqueville and wrote his bok around the same time as AdT. There is a very interesting chapter in which von Haxthausen discusses the differences between the German(ic) and the Russian aristocracy (their inheritence practices and attitude towards serfs & land), emphasizing the Germans’ focus on preserving the land within the family. The whole chapter is fascinating and I found the comparison spot-on and relevant, even after all these years.

Regards

thanks.

I love that kind of thing.

how subtle cultural differences manifest in unexpected ways.

My own Czech(Bohemian) ancestors were NOT Noble,lol…but had the same pragmatic bent, and were not known for being “passionate”….but they ultimately succumbed to the Anglo-American regime of the locust.

Yes, Germanic/Central European immigrants tend to fly under the radar in terms of their formative impact on American society. But I have long noted that German last names disproportionately predominate at American industrial (non-FIRE) C-levels, military flag ranks, etc. The old stereotype of always seeking Order has some basis in truth.

On the larger topic, privileged birth means more than inheritance. Second sons took their superior nutrition, social rank and education to careers in the Church, the military and the civil service, and this was formative in the rise of nation states, whose key servants were tied by blood to the landed elites.

Lastly, I would note the undeniable countercurrent, that inherited wealth dissipates over time, as stated in the 17th century haiku:

‘House for sale’, he writes

In the finest calligraphy style

The third generation

Inheritance is a perfect example of how meritocracy is a classic example of a “big lie”.

How can society be a meritocracy if the starting point is not a level playing field? We have people who are born to impoverished parents and those who inherited their money.

Then those who inherited their parent’s money can leverage their professional networks, get into the best private schools, never have to worry about coming up with enough money to survive, go to the best universities, use the alumni networks to get great jobs after they graduate, etc. Sure, they may work, but their challenges are much smaller than the poor, who must work far harder and get paid much less.

Conservatives see the rich as morally superior. So too do many Clinton Liberals, as Thomas Frank noted in his book “Listen Liberal”. In the context of inherited wealth and being raised from wealthy parents, that makes zero sense.

The obvious solution would be to have a steeply progressive inheritance taxes. Of course the Conservative and Neoliberal folks claiming that society is a meritocracy are opposed to this in a hypocritical fashion. This will lead to aristocracy. Actually it already has in a way.

http://econintersect.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/great-gatsby-curve-2.jpg

Social mobility is very closely correlated to inequality. America is a caste like society. Notice that it is on a category more with developing countries

aye. that’s the grand hypocrisy in the “we’re a meritocracy” mythos.

it ain’t meritocratic if what your parents/grandparents did matters more than your own personal Merit,lol.

I think it’s remarkable how we are so averse to talking about this, in “polite” society…I remember noticing the utility of choosing the right parents in the town I grew up in, but such observations were decidedly unwelcome, save as jokes in private.

It was in poor taste(!?) to notice.

add in the strategy of calling the obvious remedy(estate tax) a “death tax” and somehow convincing a great majority of people I have known(in Texas) that it might someday effect them(even dishwashers!).

it’s really quite incredible, and showcases the skill of the folks who wage the mindwar.

I think there is a lot to be said for a family to be able to pass on a limited amount of wealth to the next generation. I think that is the essence of the American Dream – to be able to build wealth of your own and kick-start the next generation.

So I think that an inheritance exemption in the $1 million to $10 million range is reasonable to allow small business to get passed down relatively intact. Once you start to get around the $10 million range, it is hard to call that “small business” or “family farm” anymore (5% – 10% NOI would be $500k – $1 million annual income). Inheritances in this range will generally force the next generation to do something to add value or that familly will end up “short-sleeves to shirt-sleeves in three generations).

Above $10 million, I think there should be pretty high inheritance taxes (35% at a minimum and preferably around 50%) designed to disrupt the inheritance structure, force sell-offs etc. to force Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” process to occur. Trusts should have stringent rules focused on disbursing the contents of the trust within a generation. Only people with certified disabilities should be able to be the recipient of a trust that spans multiple generations (a good attorney will likely argue that “affluenza” is such a disability.

I also think all income should be taxed the same – capital gains, dividends, interest, wages & salary. I don’t buy the hype of capital gains preference as a job creator.

yeah. I agree, but would quibble with the numbers, perhaps.

since my joints started to go, and my boys were born(simultaneous phenomena), all I’ve wanted is to make some kind of relatively stable homestead out here…like what wasn’t there for me when world ground me up.

so no debt, nothing that needs a permit(composting toilet saved me about $8K), permaculture, and make myself indispensable to the locals(I’m the organic/sustainable/1850’s tech guru with the classics library).

there’s nothing out here that Empire wants(except that damned special sand!)

finally talked mom into lawyering up and doing some trust thing to protect the place(20 acres. well under a million $’s, unless price discovery has truly gone mad)

They sure don’t make it easy,lol

Re inheritance and inequality: Any change in all this passing and concentrating of wealth, down through the generations, requires changes in “the law.” And Who Writes The Law, again?

The other option is to separate heads from bodies, one way to terminate succession, though we kindly progressive mopes can’t do that beheading now, because we learn that the brain lives on, with its senses fading, for ten or more minutes after the head is severed from the neck, and that is HORRIFIC and.CRUEL, unlike what the Lords used to do to mopes by gutting, drawing and quartering us, the rack, the Iron Maiden and all that fun. And of course the Bourbons du jour already, like those wig-headed fops of yore, have mostly moved their asse(t)s out of geographic and “legal” range of the People Of The Pitchfork and Torch…

(I also see from a post last week or so that “time” is an imaginary construct, so why we mopes worry about inheritance and inequity and their effects, I don’t know, except that my personal sensorium perceives pain and loss in a linear fashion — before, during and after “events,” and injustice and unfairness and cruelty all have a temporal component. Many would reliably assure us that pain and loss and subjection are either just Grand Illusion to be mastered, or God’s Will…)

Might it be the case that there are unidirectional flows in whatever is the nature of the situation we live in? That power and wealth always concentrate, that the concentration causes pain and death and destruction of people and place, all for the pleasure and dominion of the few who are wired for or born into the opportunity to loot the rest of us?

You say ‘who lived “on money that were invested they hardly knew where?” (Orwell 1968)’ but there was another dynamic change occurring in 19th century as the British national economy changed from one based on land ownership under the control of the King’s friends to one based on the bond market under the control of the new banking class.

That change was due to national bankruptcy in the wars against democracy. Many peers lost their fortunes by failing to respond to it, the Buckinghams being pristine examples.