By NewDealDemocrat. Originally published at Angry Bear

This post is a comprehensive update as to the cost of new and existing homes vs. renting, all measured compared with median household income. As such it is epistolary in length. So here is the TL:DR version:

- as a multiple of median household income, new home prices are at an extreme beyond even the peak of the housing bubble, while existing home prices are about 5% under theirs

- but unlike then, when apartment vacancies were high and rents cheap, now rents are *also* at an extreme as compared with median household income

- even with their recent increase, interest rates are still lower now than during the housing bubble, so the median monthly mortgage payment adjusted for median household income is even still about 10% less than it was at the peak of the housing bubble

- if the trends of rising prices and interest rates continue, at some point they will overcome the demographic tailwind of the large Millennial generation having reached typical home-buying age. At that point there may be another deflationary bust

_____________________

Half a year ago I wrote a long post discussing “the real cost of shelter,” by which I meant not just the downpayment on a house, but the monthly carrying cost for a mortgage, and comparing both of those with median rent.

That comparison showed that, while the “real” cost of a house downpayment was at a new high, the “real” cost of median asking rent was even higher. By contrast, the monthly carrying cost of a mortgage was quite moderate. This meant that, if a buyer could find a way to put together a downpayment, home-owning was a bargain compared to renting.

As I’ll show below, six months of price and interest rate increases later, there is even more stress on both homebuyers and renters.

By way of a quick recap, I wrote six months ago that I had never seen a discussion of the relationship between the relative cost of homeownership vs. renting, particularly as a function of the household budget. The choice (or ability) to live in the residence one desires isn’t a matter of its cost by itself, but also the relative cost of the type of residence. What is the cost of a house compared with the cost of an apartment? How expensive are each of them compared with a household’s income? If both are too expensive, maybe the choice is made to live with mom and dad as an extended family.

So, here are the three relationships I’ll look at again in this post

1. the “real cost” of a downpayment on a house.

2. the “real cost of renting

3. the “real monthly carrying cost” of a mortgage

The best metric for calculating these “real” costs on a household is median household income

1.The “Real Cost” of a Downpayment on a House

In order to generate the “real cost” of buying a house, the best way is to compare the median household income with the median house price.

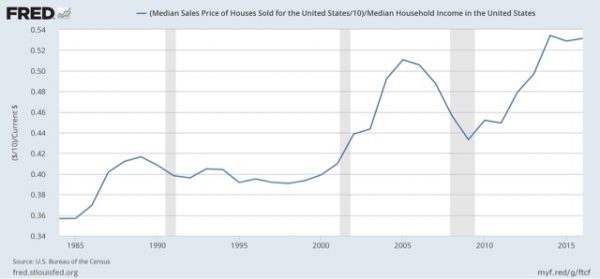

One drawback is that the Census Bureau only publishes median household income annually in September — so there is as much as a 21 month lag. Here’s what the most recent data — through 2016! — looks like:

Figure 1

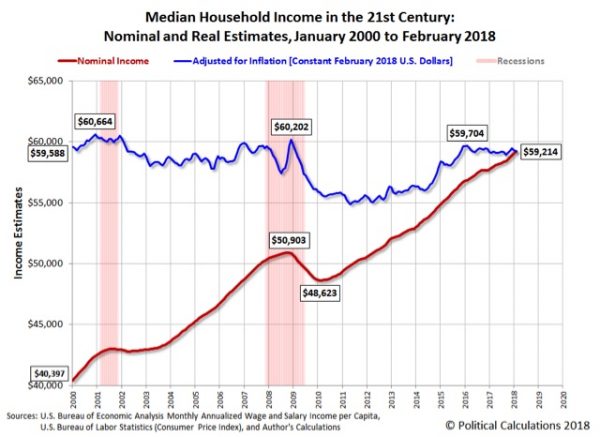

The good news is that Sentier Research published monthly estimates based on the Household Survey into 2017. The bad news is that they discontinued this service a year ago.

The renewed good news is that the website Political Calculations has picked up the mantle and continued to estimate the monthly change in median household income. Here’s what that looks like as of their most recent update through February:

Figure 2

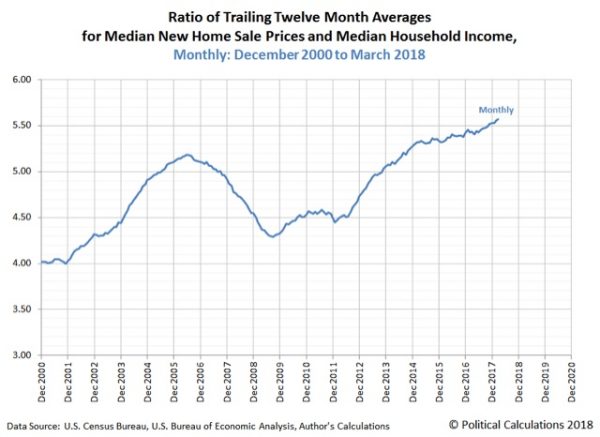

After I engaged in some correspondence with them, last week they updated their metric on “real” house prices making use of their monthly median household income estimates (NOTE: here nominal values are used for both median income and median prices):

Figure3

Figure3

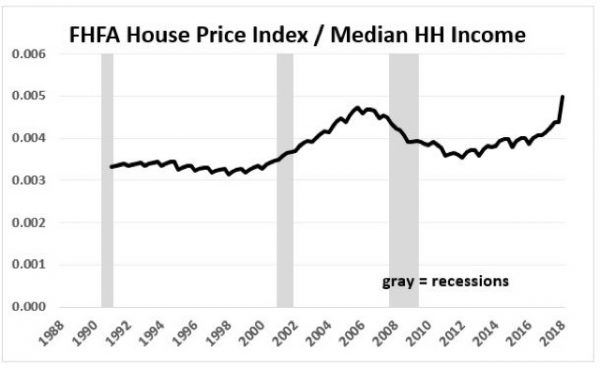

While they use new home sales for their median house prices, we get the same result if we use the FHFA house price index:

Figure 4

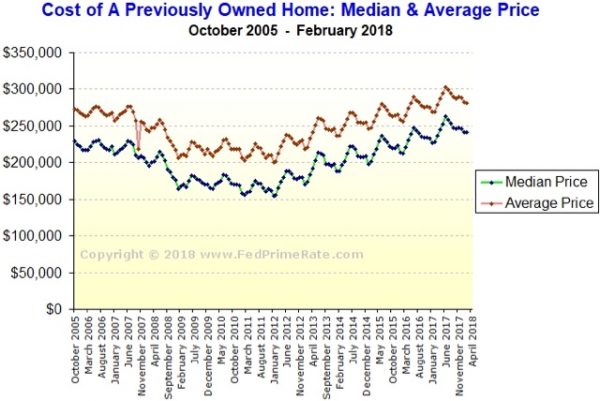

Meanwhile, the median price for an existing home, which peaked at $230,000 in summer 2005, has continued to appreciate at nearly 6% a year this year:

Figure 5

If that pace continues, by this summer the median price will be about $280,000, 22% above the bubble peak. Since nominal median household income has increased about 25% over that same period of time, they will be only aabout $7500, or about 3% below their “real” bubble peak.

In short, no matter how you measure, in real terms house prices are at or near their most expensive ever, even including the peak of the housing bubble.

So, why haven’t home sales rolled over? Part of the reason is the demographic tailwind I discussed last week. Because Millennials of peak first-home-buying age now number about 15% more than the Gen Xers of 2005, a build-up that has grown year after year for the last decade, it presumably takes even more financial stress to overcome that tailwind.

But there are two other reasons why home sales haven’t turned negative yet: the relative (un)attactiveness of renting, and the monthly carrying cost of mortgage payments. Let’s look at each of them in turn.

2. The “Real Cost” of Renting

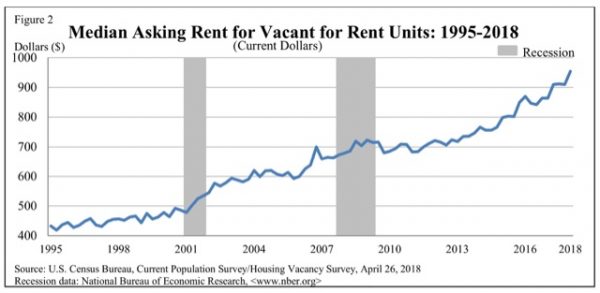

Here is the median asking monthly rent for an apartment in the US since 1995 (note: the series goes back to 1988):

Figure 6

In 1988 the median rent averged $343 per month. In the first quarter of this year it was $954.

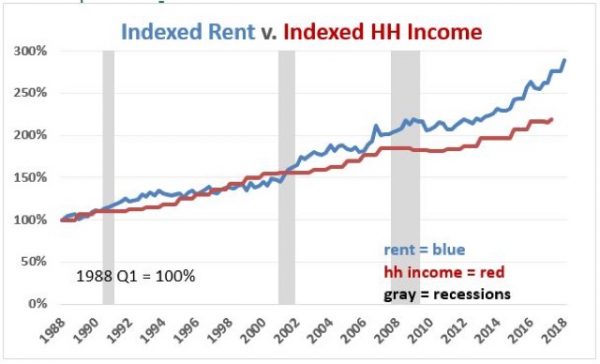

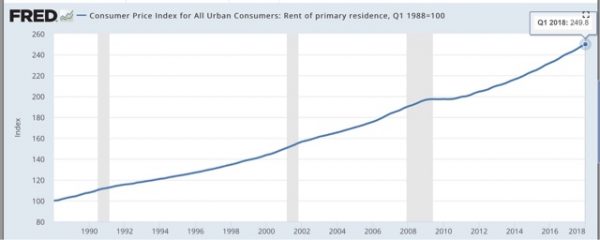

Now, here is what it looks like in comparison with median household income:

Figure 7

Figure 8

So one very big difference between the present situation and that at the peak of the housing bubble is that renting was a *much* more attractive option 12 years ago than it is at present.

3. The “Real Monthly Carrying Cost” of a Mortgage

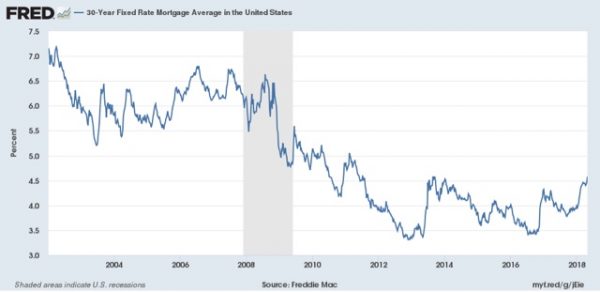

A second big difference between the present and the housing bubble is that mortgage interest rates generally ranged between 5.5% and 7% then, but quickly fell below 5% in this expansion, all the way to a low of 3.3% in 2013:

Figure 9

Recently they have risen significantly.

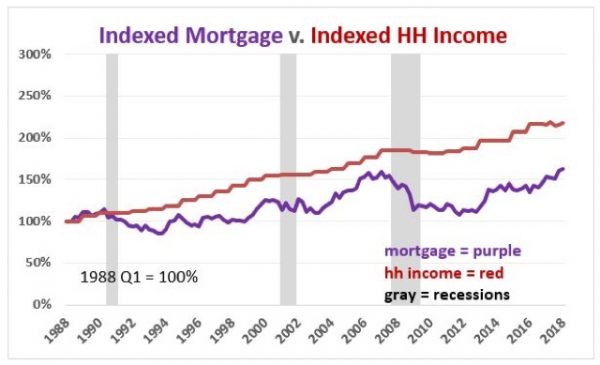

With that in mind, let’s take a look at the monthly cost of living in a house. The below graph shows the median monthly mortgage payment for a house (blue) compared with median household income (red). Median monthly mortgage payment is calculated by using the median house price and the 30 year mortgage rate for each quarter, and consulting an amortization table using those values. This is done by showing the percentage of median monthly income (1/12 of the annual) that one month’s mortgage payment consituted (note: I am assuming a 10% down payment, with 90% mortgaged to be consistent. Using a different down payment does not change the shape of the comparison at all, only the nominal values):

Figure 10

Last year, when I first posted this metric, the monthly payment for the median house wasn’t extreme at all, but rather very moderate in terms of the long term range.

- Going back to 1988, the median mortgage payment was slightly over 40% of median monthly household income.

- This fell back under 28% at the end of 1998 before rising to 32% in 2000.

- After falling briefly, at the peak of the housing bubble in 2005 it had risen to 31.4%, and actually reached a secondary peak in Q2 of 2006 of just over 35% of median monthly income.

- At the bottom of the bust at the end of 2011 it made a new low of 23%.

- As of Q2 of last year, the median monthly mortgage payment was still less than 24% of median household income.

- BUT, with the increase in both house prices of over 5% YoY, and the increase in mortgage interest rates to 4.28% as of Q1 2018, that has now risen to 29.5%

Mortgage payments for new buyers in 2018 and not nearly so moderate as they had been earlier in this expansion. But they are not yet at the extremes they were in 2005 and 2006.

4. Comparing Rent and Mortgage Payments

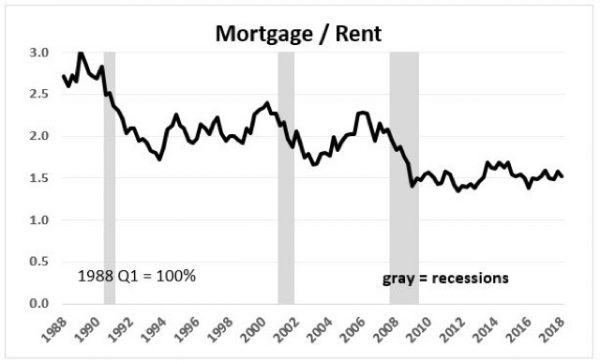

In our final comparative graph, let’s see how median monthly rent compares with median monthly mortgage payment:

Figure 11

The overall trend in the last 30 years has been that monthly mortgage payments have fallen from over 3 times median rent to about 1.5 time median rent now. Put another way, even at the peak of the housing bubble, the monthly carrying cost of a house was about 2.3 times the median cost of renting an apartment. At the bottom of the bust, that fell to 1.4 times the cost to rent. For the last five years, monthly mortgage payments have hovered near 1.5 times the median asking rent.

What is particularly noteworthy is that *even with* the recent big increase in mortgage payments, rents have also increased so much so that the 1.5 ratio still holds.

Concluding Remarks

By comparing the “real” cost of housing to renting, both in terms of down payments and monthly mortgage payments, we can make sense of some of the biggest trends in the market for shelter.

Record down payments are keeping an increasing number of prospective buyers, especially first time buyers, shut out of the market for buying a house. An enormous number are living in apartments instead. This explains both the multi-decade lows in the homeownership rate as well as the recent 30 year lows in the apartment vacancy rates, as a disproportionate number of adults are forced out of home ownership and into apartment dwelling.

But even with the recent increase in mortgage payments, in relative terms they are still lower than they were at the peak of the housing bubble, and a relative bargain compared with their historical multiple of rental payments. In short, if one can get past the down payment, home ownership still looks like the better choice.

Along with the demographic tailwind, the *relative* inexpensiveness of monthly mortgage payments vs. rental payments goes a long way towards explaining why single family home construction has continued to increase in the face of higher mortgage rates.

That being said, with increasing financial stress showing up across the board in the costs of both buying and renting, we can only expect to see even more involuntary extended family households and involuntary unrelated housemates. Further, *if* interest rates and housing costs increase much further — most importantly, if home builders continue to focus on only the most expensive segment of the market — at some point they will overwhelm the increased numbers of home-buying age Millennials who have been buoying up the market. Sales will turn down, followed by home values, leading to another deflationary bust.

[Special thanks to Mike Kimel for preparing the customized comparative graphs used in this article.]

The ownership vs rent debate is never ending.

There is a case to be made that, in the U.S., one never really “owns” their house; property taxes.

Even with a free and clear title; if you fall behind in your property taxes you can lose your home.

There are countries that do not tax one’s home or the property it’s built on, ever. I live in one, with my wife, and we paid off our home last February. Now we just pay for water, electricity, and garbage.

We’re both retired and can enjoy life without that concern (property tax).

Property tax is a regressive wealth tax. For the majority of Americans, their major wealth is tied up in their home. The top 1% has most of its wealth as financial wealth.

Wealth distribution by type of asset, 2013

———————————Top 1%——Next 9%———Bottom 90%

Principal Residence———9.8%———31.1%———— 59.2%

Investment assets———- 51.5%——–37.0%————-11.5%

The only wealth tax we have is the one on property which falls most heavily on the middle and lower class. Gee, I wonder why that would be?

Just to add insult to injury, you get to pay this tax not only on the equity of your home (your actual wealth) but also on the unpaid principal, which actually is wealth that the bank owns.

Agreed. Thanks for the chart, helpful.

Not just property tax, but home owner association fees for all apartments and town homes, and most new housing developments. Very high in SF Bay Area – around $400 a month.

If you own your own land/house in proximity to any metropolitan area of the US you are definitely not lower class.

Lower class, low skill workers are doomed to renting indefinitely unless our monetary system and tax laws are completely overhauled. Owning your own home is a definite sign of one’s arrival among the middle class, at least in the coastal metros.

Property taxes probably hit renters the hardest. Rental property usually is taxed at a higher rate than owner occupied residences. That tax burden is an overhead that is immediately passed on to the renters.

‘There are countries that do not tax one’s home or the property it’s built on, ever.‘

This is true in much of LatAm. Assessments against privately-owned dwellings typically are for small-scale charges like garbage and street lighting. If you fall into arrears, they don’t sell your house out from under you.

Property taxes in the US were once modest. No more: in some northeastern tax hells, property taxes on ordinary middle-class dwellings are well into five figures — a level that’s objectively confiscatory.

Once upon a time in the us property taxes where also levied on intangibles such as bank accounts (I recall seeing notices in the 1960s that banks picked up the intangibles tax on accounts in Michigan for example). Florida apparently had such a tax on stocks bonds etc until 2007:https://www.cga.ct.gov/2007/rpt/2007-r-0197.htm This tax apparently started in the 1920s. But there were ways around it so that apparently it did not raise much revenue. (One way to escape it was if rich enough offshore accounts which from FL where easy to set up in the Bahamas) (What the state does not know (and the feds to boot) does not get taxed) Of course offshore accounts have been cracked down upon. The tax rate in Fl was .05% of the value. It appears that in the mid 19th century there was a move to put taxes on all property tangible and intangible nationwide. (Il evidently introduced such a tax on admission to the union) many such laws also excluded some types of property. But it was a self administered tax i.e. you had to report to the assessor what you owned and of course under reporting was extremely common.

Interesting discussion: It leaves out why property taxes make real estate prices stop soaring into the stratosphere.

See realestate4ransom.com for the alternative to the above.

How bad is bad in the USA? Here in Singapore, I’m sharing as a student an apartment(3 bedroom,3 bathrooms/toilets, one kitchen, one living, one dining room,one storage room) with 4 students for USD2100. For how much can I get that in the USA?

Location location location. In a rural community with a below-poverty wage base and no jobs, that house will rent for $800.

In a chi-chi college town with blue rivers and mountains, a great airport, and proximate protected public land amenities and ski areas, per- room-mate rents have run up from $350/person 10 years ago to $600 today. Lots of work (new construction and restaurants) or very high tech micro manufacturing) but because it is a college town that everyone wants to be in, wages are very low, with the average duration of stay three years, and a new wave of mountain-eaters arriving every day to take the crappy wage and eat the mountain.

A developer/employer’s wet-dream…

The USA is a really, really big place man, each state is basically a separate country, and we’ve got metro areas much larger than all of Singapore.

But, in general, in a major city the rates are comparable to what you pay, and from what I see online, Singapore has American housing beat to shit at that price range.

If you want to live out in the country like I do, but still too close to a metro area then things are like 1000 USD for 2 bedrooms 1 bath. Apartments are about 800 for a studio (I think utilities are included there tho)

Way out in a small town nowhere near any city rent gets as low as 300 USD for a 2 bed 2 bath. But you’re not going to have anywhere to work.

That sounds fairly comparable to US rents. In some rural areas you might pay significantly less, and in larger cities like Seattle, SF, DC, NYC you would probably pay quite a bit more.

Location is a big determinant. In the San Francisco Bay Area, a one bedroom apartment in San Francisco itself is around $2,200 while a two bedroom is $3,200. It’s significantly more in Silicon Valley. Fifty miles north of San Francisco it is about half. Keep in mind that these are average prices. With a bit of luck good or bad, one could be paying a few hundred dollars more, or even less, for a average apartment.

Housing costs in much California is like that boiling pot of water that slowly killed the frog. Just about every year it is a little harder to pay for a roof.

Thanks for a detailed post on this issue, one quibble not everyone has parents or extended family that will have them, and in the current environment of chosen winners from zirp et. al. the losers are truly viewed as such…walking through mt. vernon, washington yesterday, looking for a nice path through the woods but it’s pretty much “campers” (camping?hey that sounds fun……but not this kind of camping..).and it’s pervasive, every city thinks some other city is sending their homeless to them, but these are your former neighbors. And the rental market is absurd. If you don’t have good credit and many thousands of dollars in the bank, that will be gone as soon as you find a place. Good Luck. The impending downturn is going to make 08-09 look like a party.

Yes to the “camping” metaphor.

The incidence of panhandlers on street corners has expanded mightily recently.

Are we seeing the resurgence of pseudo hunter gatherer bands in the so called ‘First World?’

Out here, the downturn has already begun, ’employment’ statistics notwithstanding.

“Klaatu barada nikto.”

I think a huge part of the homeless problem here is that no way can you afford an apartment on a mi wage job. Rental prices out on the Left Coast are nuts.

One cost of ownership seldom mentioned in studies like this is the cost of maintenance and repair.

I work as a Broker Associate in Sonoma County and we appear to be past the peak in prices for this cycle based on what I see of homes going into escrow recently.

It won’t show up in the numbers until these deals start to close in a month to six weeks and prices are sticky on the way down but it has clearly begun.

How fast and how far prices will drop is anyone’s guess, mine is 5% by late fall locally.

That guess is totally unscientific and based entirely on gut feel.

Interesting times…

I

Yes, good point; maintenance and repair are not small expenses.

Property taxes never go down and can be hundreds of dollars a month on top of everything else.

Yes these costs have to be considered, but there is a flip side to that… when one owns, one can remodel to one’s heart’s content, including making changes that will reduce fixed (utility) and maintenance costs. Renters often have to put up with a large number of design disamenities, sometimes you can’t even change the color of the walls, never mind putting in a more functional kitchen or bathroom, a solar collector, green roof or composting toilet. You always know you are living in someone else’s space, not your own.

OTOH, if you aren’t in an ARM, you know exactly what your fixed costs are. Out here in SW OR, rents have gone up between 15% -25% since the great recession. Wages sure haven’t. And you can’t be evicted because the owner wants his mom to move in, or turn the place into a condo. I dearly hate moving.

OTOOH, it is your deal when the water heater blows up. But I prefer the security of knowing my costs. Where I am now, I could put $8K/yr into the house maintenance or remodeling and still be ahead of rent, and build equity at the same time. Pretty much a no brainer.

Because credit (a money equivalent) can be created essentially without limit, that means the amount of money (credit) available will increase ad infinitum. Any slowdown in credit increase is a deathblow to the financial system.

This means that assets will always be in short supply compared to the credit, ie they will keep rising in price. Housing is the best asset in this explanation as banks lend for housing at the bat of an eyelid.

What it does to the next generation’s chances and in terms of generational fairness – i’m not going there.

There is another cost associated with home ownership that people often don’t realize in larger cities.

Cost to drive to work and amount of time spent. Big cities mean that unless you live in an area close to work, which if it is in the downtown area is usually very expensive, cost to drive is going to be a big deal. You are talking about fuel, maintenance, higher depreciation, insurance, and other costs with car ownership. Plus lots of your time is spent in annoying traffic. This is where buying a condo in downtown might make sense.

From my experience, the bigger the cities, usually the more the traffic issues and commute time.

I think this is mostly an argument for renting as you never know where your next job will be and so any buying can easily end up with the commute from heck.

I live in an urban intentional community and our rents, due to sharing, are at the 1988 levels depicted in one of the graphs above. I know intentional community is not a big thing these days, so maybe not very many people are interested in this. But I took note when the author mentioned “involuntary unrelated housemates”.

Lately when we have space for new housemates, we get a huge number of people inquiring who haven’t the slightest notion of what intentional community is, nor any real desire to share or live communally. They are attracted solely by the low rent. This has made it difficult to sustain our community over the last few years. Of course, when interviewed, everyone swears they are interested in living communally. But we have had a series of quite charming people move in who then proceeded to act as if their room was a private apartment. Showing a near contempt for our public space and socializing, they would virtually lock themselves in their rooms, demanding their privacy and the right to live in complete isolation from the rest of the house, refusing to contribute time or labor to the house until we booted them out. Not good for them and not good for us. But at least the rent was always paid… : )

Huh, I would like to know more about this. Is it like a coop?

On a semi unrelated note — why do we treat the US as one, big, homogeneous market? That doesn’t even work at the county level, let alone a country larger than the EU, and just as economically diverse (if not remotely so culturally diverse).

We have a semi-unified culture, and pretty dang free trade between states — but comparing the housing market in NYC or even DFW and, say, Amarillo is just silly. We don’t even have common laws. The economies aren’t exactly comparable, let alone any specific market. Averaging between them just hides the interesting data.

It’s also brilliant at making the extremes disappear.

But, but, but… Inflation is below target. Right? https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20180406a.htm

“With the economy improving but inflation still below target…”

“But the decline in inflation last year, as labor market conditions improved significantly, was a bit of a surprise.”

One wonders if they’ve ever looked at housing costs. I personally believe that ultra-low interest rates have significantly contributed to these ever-climbing rents and housing prices, but you’ll never hear such words from the Federal Reserve.

inflation in the US is always below target, reportedly, allowing more stimulus.

feature not bug.

I’ve been thinking about inflation lately. Surely they don’t factor in the cost of higher education or health care. The cost of college has been rising at roughly 3 to 5 times the rate of inflation, and health care is just as absurd.

If these costs were factored into inflation, then just about everything else would have to be getting cheaper and cheaper to compensate.

Big Screen TVs — I see a 65″ 4K TV for $680 — are the Opiate of the Masses.

Mortgages and rents have increased the most in the Western USA- about 11% compared to the 6% nationally. It gets weekly coverage in the local news, here. Developers are building like crazy, and my city is trying to give developers money to build affordable housing, which I think is opposite what they should do.The problem with affordable housing is that it prices out millennials like my husband and myself. Low rents and high rents but nothing in between. We’re not poor. We’re not middle class. We can’t get rent subsidies, but can’t afford rents. I’m lucky to live in somebody else’s parent’s basement with affordable rent because they totally get it.

On top of our doubling of housing prices in the last ten years we have a major homeless problem. My county is trying to house homeless people, but only give them 3 months worth of subsidies and putting them in run down homes that cost $1,000/month when these people barely have jobs. All of their money goes to rent, and they end up right back on the street, but now with an eviction.

My husband and I are considering a tiny house. It may not be a sound investment, but it’s low resource use if built correctly, and that’s something that matters to us. Now if only we could connect one to the grid instead of being off grid in a city.

In Figure 2, the blue line shows that real median household income has been falling throughout this century. In fact, the chart could be extended back to the 1970s with the same result.

Fact is that a militarized bubble economy simply cannot deliver the goods in terms of rising living standards. First the global military empire dissipates the capital that should have been invested domestically in infrastructure and human services. Then the leveraged, financialized bubble economy delivers wealth to the already wealthy in the form of capital gains. None of this trickles down into income for the middle class.

This wretched economy is profoundly broken. It will carry on sinking until two sacred cows — the military empire and the Federal Reserve — are challenged and brought down. Smash NATO, smash the Fed.

Tell it, Brother!

Is it a coincidence that “Sentier” rhymes with “Rentier” and are only one letter apart. Maybe not if one is pronounced the French way and the other the English way.

Just askin’.

The US has skimped on its Ricardo.

“The interest of the landlords is always opposed to the interest of every other class in the community” Ricardo 1815, a classical economist who knew housing costs should be kept low.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

The minimum wage is set when disposable income equals zero.

The minimum wage = taxes + the cost of living

US businesses want a low minimum wage, but haven’t realised high housing costs are part of the problem.

Don’t skimp on your Ricardo.

Economics was always far too dangerous to be allowed to reveal the truth about the economy.

The Classical economist, Adam Smith, observed the world of small state, unregulated capitalism around him.

“The labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

How does this tie in with the trickledown view we have today?

Somehow everything has been turned upside down.

The workers that did the work to produce the surplus lived a bare subsistence existence.

Those with land and money used it to live a life of luxury and leisure.

The bankers (usurers) created money out of nothing and charged interest on it. The bankers got rich, and everyone else got into debt and over time lost what they had through defaults on loans, and repossession of assets.

Capitalism had two sides, the productive side where people earned their income and the parasitic side where the rentiers lived off unearned income. The Classical Economists had shown that most at the top of society were just parasites feeding off the productive activity of everyone else.

Economics was always far too dangerous to be allowed to reveal the truth about the economy.

How can we protect those powerful vested interests at the top of society?

The early neoclassical economists hid the problems of rentier activity in the economy by removing the difference between “earned” and “unearned” income and they conflated “land” with “capital”. They took the focus off the cost of living that had been so important to the Classical Economists to hide the effects of rentier activity in the economy.

The landowners, landlords and usurers were now just productive members of society again.

It they left banks and debt out of economics no one would know the bankers created money out of nothing and that the monetary system required prudent lending to function correctly. Bankers would be free to do what they wanted.

The problem.

Once you have tailored economics to look after powerful vested interests, it just doesn’t work anymore.

Looking after bankers in economics leaves you open to endless financial crises.

William White (BIS, OECD) can also see how economics took a wrong turn over 100 years ago.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g6iXBQ33pBo&t=2485s

Banking theory has been regressing since 1856, when someone worked out how the system really worked.

Credit creation theory -> fractional reserve theory -> financial intermediation theory

“A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence” Richard A. Werner

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1057521915001477

11.1 million “unauthorized migrants”…deserve their own housing.

Wonder how many low rent housing units they occupy?

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/reports/2017/04/20/430736/facts-immigration-today-2017-edition/#fn-430736-9

Please give a humanitarian definition of “unauthorized.” The way I would define authorization for migration would be that those whose physical nations have been destroyed by your military adventurism have first authorized call on housing in your country. Second would be those whose country your foreign policy, backed up by military threat, has destroyed by removing all its resources with the aid of its local proxies, or by demanding its financial system be beholden to your bankers and financiers. Those definitions would involve hundreds of millions? or a billion? or so of humanity. Those would be the “authorized migrants” the USA and its European, Canadian, Australian and other imperial powers would admit, if those powers had any ethical premise for existence.

I’ll make sure and tell all my senior friends who are desperately looking for housing and their children plus a few nurses at the hospital and homeless veterans I run into of your “humanitarian” rental allocation scheme. Maybe I could send them north to your country?

1/5th of Mexican working age males are in the U.S. That allows the oligarchy there to remain in power as the potential troublemakers and their surplus population are sent north, plus they receive hundreds of billions of dollars in remunerations from the U.S. which robs our local communities of that money.

“Unauthorized”= “Not citizens or lawful permanent residents”

How’s that for a definition?

What the [family blog] does “unauthorized” immigration have to do with inflated housing costs?

Where do those 11 million unauthorized immigrants live? Housing is scarce enough without 11 million extra people vying for it.

20 metro areas are home to six-in-ten unauthorized immigrants in U.S.

Also not helping the scarcity problem: – landlord, developer, and gentrifier political influence; property and other tax policies; zoning policy; lending policies; public housing policy; availability of support services for homeless/mentally ill/substance dependent/elderly people in need of housing; the mix of public transportation, jobs, and housing in any given area.

Politicians and influence peddlers pushing for deportation aren’t doing so because they have an interest in solving housing or employment problems. If they cared about housing, they’d be attempting to solve all these other factors instead of neglecting them, or making them worse.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860281/

Perhaps you would like to read a report on housing. Unauthorized immigrants overwhelmingly live in substandard housing. I seriously doubt millenials are competing with them to live in slums.

Perhaps you would like to take issue with the 40 million legal immigrants.

“I seriously doubt millenials [sic] are competing with them to live in slums.”

That’s the same old rehashed argument about illegal immigrants only taking jobs that Americans are unwilling to take. The fact is, Americans would take those jobs, but the employers might need to pay a reasonable wage. Why are we letting the employers off the hook?

And if the landlords would fix up the housing so that it is humane, as is the right thing to do, then the millennials would take what is now considered “slum housing.”

In addition to the points raised in the comments re property tax and maintenance, there needs to be a risk premium factored in to sinking most of your life savings into what should be considered a depreciating asset that can take months or years to liquidate.

Any longer view, generational analysis of housing costs should really consider the implications of how our income tax brackets and estate taxes have shifted over the course of a single generation. The changes in US tax policies have greatly impacted the ability of individuals to amass great wealth and easily transfer it to their heirs. This has to be impacting the housing market in a significant way.

Among all the home owners my wife and I know under 40 in Los Angeles every single one of them used inherited or gifted money for the down payment, or they were from extremely high paid careers fields ( finance, medicine, Orthopedic Surgeon, Private equity, etc.) From my observations, regular people without rich parents or some inheritance coming from a relative cannot afford to buy a single family home in any of the major coastal metros.

In 1979 the estate tax was applicable to any estate over $147,000, dollar amounts beyond that were taxed at 70%. Now estates of 5.2 million per parent are exempted, meaning parents or grandparents can pass almost 11 million dollars untouched to the heir of their choosing. How could that not skew the housing market? In 1979 a married couple earning $45,800 found themselves in a whopping 49% federal income tax bracket. In inflation adjusted 2018 dollars that same couple today would earn $157,000 but would be in a 28% tax bracket. As significant as that change is, the real difference is most apparent at the top.

Is a bubble characterized by excessive speculation? What about affordability? If house prices are historically high relative to incomes but there is no excessive speculation, then it is not a bubble? Bill McBride seems to think so.

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2017/10/are-house-prices-new-bubble.html

A lot of talk about rent vs buying. I imagine it does differ from place to place. That being said, then this isn’t a bubble?

And not a single mention of climate change: everyone wants a single family home nevermind the carbon footprint or transit options. Sigh.

Purchase price of a home in my area is currently x10 annual income. A tear down is x4 income for an illiquid asset. It’s just not worth it.

I think the biggest advantage for those able to buy (and assuming a fixed interest rate) is the fact that you have secured housing with a payment that will not increase year after year. Sure, you property taxes will go up, your insurance may go up, but your mortgage payment will remain the same. Not much advantage to homebuyers in the first several years, but quite soon you reach a point where the amount of rent that would be charged for the same house has increased by 50%, 100%, 200%, and you are still making the same payment.

The catch to this is that this depends on a more-or-less guaranteed income tied to a likely regionally fixed job. Particularly among the millennial generation, restricted/limited entry into “real jobs” (i.e. those that pay a livable hourly wage and provide at least a minimum of benefits like an employer healthcare plan, 401k/403b, etc) often means that our generation has to be highly mobile in order to secure meaningful employment. Couple this with the generational toll on purchasing power due to our historically way above-average student loan burden and stagnant wages and it’s easy to explain why there is so much upwards pressure on rent.