Earlier this week, we linked to a CNBC story that described how the Department of Education is seeking input on whether it was too hard for borrowers to discharge student loans in bankruptcy. We pointed out that if the DoE went forward, it would be a twofer for the Republicans: they’d probably win votes from at least some borrowers who benefitted, and the recognition of losses on Federally guaranteed loans would lead to call to make the program more stringent, perhaps including penalties on higher educational institutions who mislead borrowers about loan risks and their earnings potential. Since employees of higher educational institutions skew Democratic, effectively cutting their funding would not hurt and probably would help Team R.

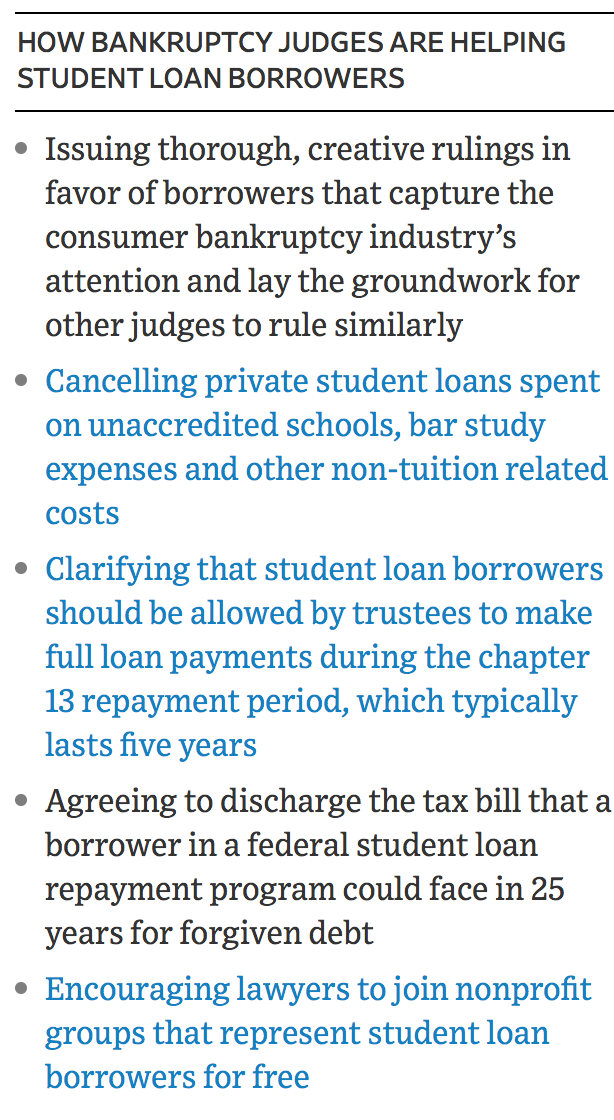

It turns out some bankruptcy judges have already concluded that the bankruptcy requirements for student loans have been excessive, and they’ve been allowing some borrowers to reduce or discharge their debts, something that was heretofore virtually impossible.

Mind you, this is not happening very often, in part because bankruptcy judges historically have been so unreceptive to plaintiffs weighed down by student debts seeking relief that lawyers would refuse to take these cases. As a result, last year, only 473 borrowers made the attempt.

But as the Wall Street Journal describes, some judges are of the view that the past application of the standard for whether the borrower was a candidate for relief has been too stringent. The Journal buries the legal rationale and in so doing, winds up feeding the right-wing narrative that do-gooder judges try to rewrite the law and therefore represent a menace to upstanding citizens who’ve had the good fortune not to need to borrow to get a degree, or if they did, never suffered a big setback, like a serious illness, job loss, or divorce.

The legal question is that in 1998, Congress restricted the discharge of federal student loans to cases where the borrower could demonstrate “undue hardship”. Congress not define what that threshold was, and Journal’s account gives the impression that the standard that came to be applied was more punitive than what “undue hardship” meant to judges when the law was revise.. Indeed, it is hard not to conclude that most judges have been overzealous. From the Journal:

When Marie Brunner, a 1982 graduate of a master’s program in social work, tried to cancel her loans in bankruptcy, a New York judge in 1985 said she had to show three things: she struggled financially, her struggles would continue and that she had made a good faith effort to repay. She lost.

That list still serves as a baseline for hardship in circuit courts that control the rules in most states.

The article then points out that appeals court judges took it upon themselves to ratchet up the requirements:

Some appeals courts set even higher benchmarks, with one, for instance, saying borrowers must face a “certainty of hopelessness.”

Defenders of current harsh practices argue that the case law is well settled, and the Journal describes how one judge who pushed back against the current norms had his decision reversed on appeal:

Last year in Philadelphia, U.S. Bankruptcy Court Judge Eric Frank cancelled a single mother’s $30,000 in student loans…Judge Frank ruled that the relevant window was five years.

An appeals court overturned his ruling, but his decision inspired Judge Mary Jo Heston in Tacoma, Wash., in December to cancel a portion of another borrower’s loans.

More and more judges are coming around to the point of view that the current standards are a misapplication of legislative intent:

Some of the country’s bankruptcy judges are starting to argue that the prevailing legal standard is unintentionally harsh and wasn’t meant for adults still on the hook for student-loan debt years after college.

Judge Frank Bailey in Boston made that argument in an April ruling wiping out $50,000 in student loans for a 39-year-old man whose health ailments prevent him from working….

Some judges, including U.S. Bankruptcy Court Judge Michael Kaplan in Trenton, N.J., said they are looking for ways to be more forgiving after seeing their own adult children borrow heavily for their education. Other judges grew concerned after talking to their law clerks. The typical law-school student takes out $119,000 in loans, according to the legal-education watchdog group Law School Transparency.

Two judges said they regret their rulings against borrowers more than a decade ago. One Florida judge said that if the case was filed today, the borrower would win.

Kansas judge Dale Somers said he worked particularly hard to justify the reasoning in a December 2016 ruling that cancelled more than $230,000 in interest that built up on a couple’s student loans from the 1980s. They left bankruptcy owing the original amount: $78,000

Despite the signs that more and more people are starting to recognize that, as Michael Hudson puts it, “Debts that can’t be paid won’t be paid,” there was still a depressing amount of moralizing in the Journal’s comment section about how letting borrowers off the hook would encourage all sorts of profligacy and fornication, as if bankruptcy were a party. Nevertheless, even though widespread relief is still a way away, the tide on the student debt front is finally turning.

The modern American Dream?

I hope so.

While I’m glad some judges may finally be empathetic to student loan borrower plights, it bothers me that it took seeing their own children or law clerks situations to finally get there.

How many of the current judges got their education when state schools (and associated living costs) were more affordable?

When this generation’s graduates and law clerks become legislators and judges, I’d like to believe that their experiences will continue to reshape the student loan landscape (and education costs in general) for the better. It can’t come soon enough.

Agreed, and I was remiss in not calling that out. I went to college when people who were only a bit over median income could save enough to send their kids to an Ivy League school. And grad school wasn’t catastrophic either. Recall that Steve Job’s working class parents paid for him to go to Reed, then a pricey college. I don’t understand how anyone can not notice how insane higher education costs have become, and with no improvement in the education. It’s all adminisphere bloat thanks in large measure to colonization by MBAs and gold plated facilities.

I’d add that on the loaner end, I assume the Department of Education greedily collects interest.

But I have no idea how federal accounting works on student loan interest, though. Does anyone? Where does that usury money go? Or am I simplifying this? I honestly I have no idea.

Oh my. I hadn’t thought about that Steve Jobs angle. So right now we might have a ‘Steve Job’s that could build whole new industries and shape our lives in the 2030s and 2040s but that won’t happen now because our present young ‘Steve Jobs’ is too buried in college debt to ever try to do this.

I dug up some numbers on reed. In 1986 tuition there was about 17k in today’s dollars. Tuition today is about $52k. This means tuition has trippled. However per-capita GDP has doubled in that time.

This is an ‘expensive private school’, and tuition is actually up around 50% in that 30 years. A big increase, to be sure, but not the sort of thing one would think would be disasterous.

I looked up the numbers a while ago for my local big state university. I was actually amazed to find that cost per student is flat for the past 28 years (inflation adjusted). The UW Seattle spends essential the same on each student as it did in 1990.

But, hey fool, UW tuition is up way more than that! This can’t be true. For state schools tuition = cost – state support. The real story there is that state support is down. In the early 90’s the state paid around 75%, now it pays 25%. So tuition has tripled. There is no higher education cost problem at big state schools. Costs are under control. There is a ‘the state doesnt pay nearly as much of the tuition’ problem.

So luxury private school costs are up, but not at all as much as many would have you think.

Another element is that pell grants, etc have stayed relatively flat. So not only are students coming out more in debt due to higher tuition their loans are worse. Interest starts right away, etc.

But down under this is the real thing. Remember my comparison to per-capita GDP? Had I compared to median wages it would be quite different, eh?

Remember, if the US income distribution were the same as in 1970 median family income would be around 100k instead of around 60k. $40,000 every year for a median family.

Kind of changes the picture on that $52k a year tuition eh?

Anyhow, cost isn’t the problem.

Inequality is the problem. Reduced state support is the secondary problem.

Note gdp is a good comparison for things like education which have low productivity growth. One should not expect the cost of it to track just inflation.

Um, milage varies a lot with state schools. And they’ve had adminisphere bloat too. One academic said that at many CA state schools, as little as 11% of the budget was going to education (faculty and teaching facility costs).

At Berkeley, the cost for in-state students ins $36K, with the tuition component at $15K. At Rutgers, it’s $32K, with tuition $14.5K. At UVA, it’s $32K, with tuition $16.8K.

Many state universities have large research or hospital budgets that are not directly part of undergraduate education, so total budget numbers are not very useful.

And yea, you are posting a lot of 50% state support numbers. In California 40 years ago it would have been much higher, and tuition trivial.

Cost isn’t the problem, even administrators, let alone professor salaries as Biden recently claimed.

Inequality, state support.

Have to know what the problem is to fix it.

And of course corporations under the gentle profligacy and fornicating dominion of PE and VC looters, and CEOs like Frank Lorenzo and I believe the pre-presidential Donald Trump and so many more modern examples, get to “disappear” all kinds of contractual debts and obligations. Like pensions and subcontractor obligations and even, quelle horreur, BOND debt! Because BOND debt is a sacred risk-free Contractual and Moral Obligation, don’t you know? Even VC and PE “debt financing”!

Yet people here castigate fellow citizen-consumers at or near or especially beneath their economic level as “deadbeats” for daring to yearn for bankruptcy protection and the discharge and “fresh start” that at least some of said castigated and of course those totally fictional “corporate persons” have availed themselves of, “strategically” or out of personal economic desperation and impossibility or just difficulties. And yes, there are a few mopes who “cheat,” but a lot more for whom suicide is the alternative.

Yaas, punching sideways and kicking down, in full Puritan fervor, is surely a wise, decent and bound-to-improve-the-political-economy set of behaviors. Bound to increase the number of people who get a place in the lifeboats, or at least be the ones with a hand on the gunwale where a Rich Person, comfortably seated, can pry their fingers loose and hit them on the head with an oar…

Glad to hear that a few bankruptcy judges are using the latitude that nonrestrictive statutory language allows them, to craft remedies to aid what the several bankruptcy judges I dealt with as an attorney thought possessively of as “their” debtors, often to the point of shielding some evil people from pursuit by those they scammed or injured, or from statutory liabilities and obligations to clean up horrific messes. As in this case that I was involved in:

In re Kovacs

No. 82-3629 (717 F.2d 984, 20 ERC 2194) (6th Cir. September 22, 1983)

The court rules that a judgment entry requiring Kovacs to clean up hazardous wastes at the Chem-Dyne Corp. site is dischargeable in bankruptcy. The court rejects the State of Ohio’s argument that the judgment directing Kovacs to remove the wastes from the site is nondischargeable since it is neither a right to payment nor a right to an equitable remedy for breach of performance with an alternative right to payment.

https://elr.info/sites/default/files/litigation/14.20253.htm

The 1998 law with the repeal of Glass Steagall are the true lasting legacy of Bill Clinton’s presidency.

Let’s not forget NAFTA!

And MFN for China. And American membership in WTO. And the Telecommunications “Reform” Act.

At last some hopeful news. The younguns at my company, whose student loan balances far outstrip my mortgage, look with astonishment when I tell them that back in the late 70s and early 80s, small loans, summer waitressing , and part-time work during the school year covered tuition and expenses.

Wait — bankruptcy’s not a party? Obviously, these student debtors failed to learn to do it right. /S

Kidding aside, it’s pretty appalling that Judges have to personally experience something (and one’s kids experiencing it is very personal) in order to properly apply the law and administer justice. But it does explain a lot, doesn’t it?

Until there’s a fully functioning means of discharging student debt in all its ugly horrors and in its fraudulent baseless, maybe the way to force some Change is for large numbers of people to #juststoppaying. And recognize it and organize it, growing out of the reality that a whole lot of people have found themselves not able to do anything else.

And gee, recent workups by Economists ™ and professors indicate that removing the millstone of toxic debt from the necks of millions of Our Fellow Americans would result in a net increase in the near-trillion-dollar range in the vitality of the political economy. Of course those studies are all about dollars, and no attempt is made to value the reduction in pain, fear, despair and lost lives in the accounting.

Bearing in mind that we mopes are being prepped for the next big banking (sic) collapse, and our obligations to “bail out” the slicks who are engineering more of the looting same…

…maybe the way to force some Change is for large numbers of people to #juststoppaying.

You go first.

From the other day, there are lots of people who have already gone first, out of impossibility and necessity. But nice comment. Very helpful.

I think it is helpful to point out the perils that the individual borrowers face when you continually suggest that people should just stop paying. If the effort failed, then it would ruin peoples’ lives.

Now, one way that you could be more constructive in this movement would be to suggest that borrows withhold payment for a limited time period—a month, perhaps two. That should get the lenders’ attention without causing default penalties for the indentured borrowers.

The cost of higher education in the U.S. is now extremely expensive, causing massive indebtedness which besides restricting possible consumption, also induces risk-aversion (to, say, become an entrepreneur) in many graduates. The cost surge in higher education is due to administrative bloat, obscene facilities (vanity projects), and the unending supply of loanable funds to potential borrowers (who are often around age 18 when making such decisions).

Such indebtedness should be easier to discharge. As someone in my mid-30s I have many friends who graduated in their early 20s still paying down enormous loan balances, and others who have refused to pay. I myself sacrificed a great deal to ensure the full payment of my loans, so naturally feel others should own up to their debts. Interest rates should be massively reduced for existing borrowers, and the U.S. should adopt a model more similar to Australia.

Thanks for this, and for the included sidebar.

Thank you, Yves.

I really like this use of a very dry sarcastic explanation that some think helping the unfortunate is a threat to the lucky. Similar comments elsewhere sound almost as if they think God Almighty has decreed this; that the unlucky have earned their misfortune from God by their supposed impurity while the lucky are God’s Elect.

Afflicting the afflicted and comforting the comfortable is the moral, ethical, decent, even rational thing to do.

Well yes, because misfortune is a sign of God’s disfavor. That’s been the central sermon of US politics since 1980.

” a depressing amount of moralizing in the Journal’s comment section about how letting borrowers off the hook would encourage all sorts of profligacy”

No one sees any validity to this argument? I share everyone’s disgust at the debt-leveraged, skyrocketing costs of education. But I had to pass up grad programs at MIT and Harvard because I simply could not afford them; I was sober-minded about taking on that much debt. Instead, I worked my way through a state school and I’m sure my resume has a little less sparkle as a result. Does that make me moralistic, then, that I would chafe at the idea of overspending without consequences? How is that any different, morally, than Wall Street privatizing profits and socializing losses?

I was chatting with my barista the other day, and she was complaining about her $30k debt from art school. (Art school!) I genuinely pitied her until I noticed she was driving a pretty nice car. Ah, but here I am “castigating” my fellow citizens.

In short, seems to me that reasonable adjustments could be made without entirely dismissing moral hazard.

The near impossibility of bankruptcy is one dimension of the debt-peonage imposed on young people; the other is the cost of the debt, the interest rate charged and the fees.

A simple and human solution is one proposed by Warren: reduce interest rate to the same rate charged by the government to the banks as a result of the financial crisis: pretty much zero since 2007 via QE; or, if you fear moral hazard might increase through such a policy, then reduce the interest rate to the interbank rate (1/2%).

You can insist the loans be paid back but oppose the growth of those loans at the now required minimum rate 6.8% which means the capital value of the loan increases by nearly 50% during the borrowing period (being a student for the now average 4-5 years) and of course doubles if one adds further schooling delaying repayment for up to 10 years from the initial year borrowing begins.

It is this rate of growth of the debt when the borrower is not in a position to repay that is an egregious abuse of human rights, an imposition that the financially illiterate congresspeople impose on young people and ignored by the even more financially illiterate press that covers student debt stories. Most of them end up searching for a ‘human interest’ angle on an individual circumstance because compound interest appears to be something to difficult for them to understand.

This is helpful, Penny, thanks. I’m all for looking at interest rates, some principal reduction, and in some cases, maybe even forgiveness. But as with the case of the mortgage crisis, I step off when the agency and responsibility of the borrower is completely glossed over or glibly dismissed. After all, they were the beneficiaries of the item/service purchased.

Heaven forbid that Judge Michael Kaplan draw upon his own precious savings to pay for his child’s education. And those poor lawyers… Good luck garnering broad support when they’re the poster children of student debt.