Several major media outlets picked up a new report by the JPMorgan Chase Institute on the so-called platform economy. The authors published a similar report last year that contended that gig economy growth was over. The problem with this document was by attempting to look across the entire gig economy, it didn’t dig into the factors that were important in the local transportation sector. The JPMorgan Chase study, and even more so, Uber and Lyft-influenced press reports on the report, ignored the most probable cause of falling revenues per drivers and larger numbers of drivers: that churn has risen greatly due to deteriorating driver economics.

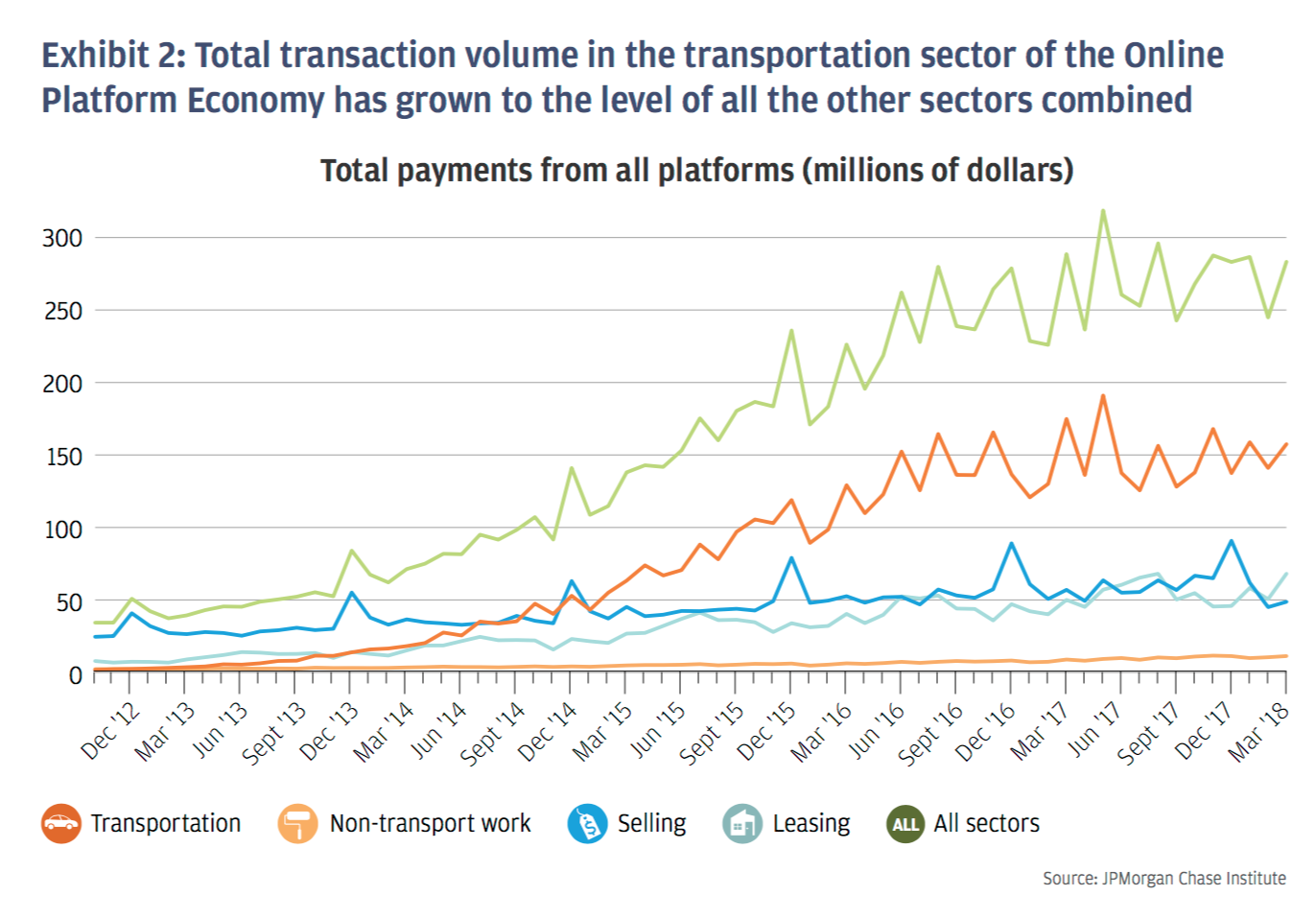

Admittedly, this chart is based on a sample of a very large set of Chase’s transaction data, but you can see the flattening of transportation revenues:

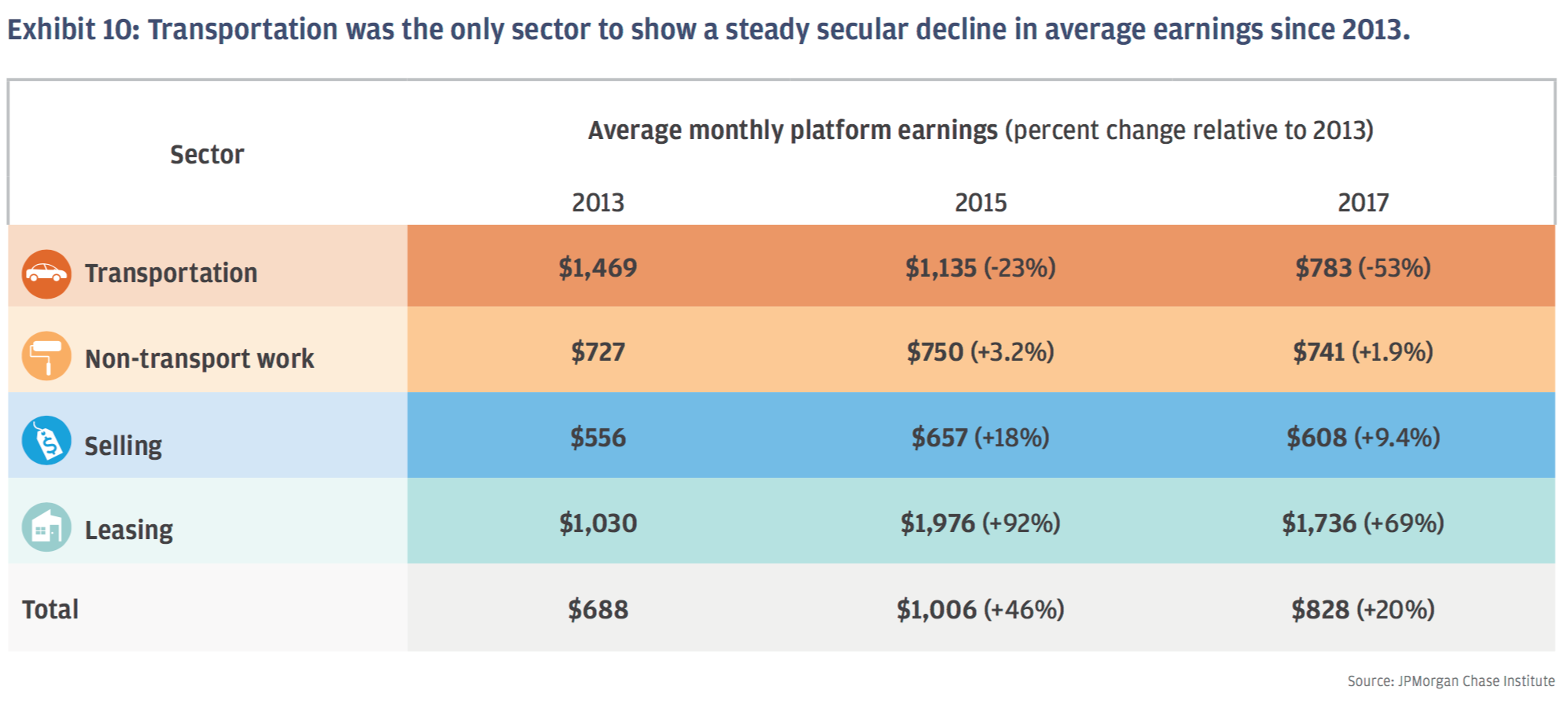

The chart below was the centerpiece of the news reports on how Uber and Lyft drivers are faring:

While the study suggests that demand and supply factors (more drivers leading to fewer average hours) is possible, the authors pointedly say they don’t know due to the lack of data:

These declines in monthly earnings among drivers may reflect the fact that the growth in the number of drivers could have put downward pressure on hourly wages; they may also reflect a potential decline in the number of hours drivers are driving. In our data, we do not observe wages and hours separately; we see only their product, earnings.

Noreover, research that goes only through 2015 points to decay in driver profits, not just gross revenues:

However, research into tax reporting indicates that self-reported costs by new drivers fell 41 percent between 2013 and 2015, whereas self-reported earnings fell 46 percent (Abraham et al, 2018). Since a significant fraction of these costs is likely to comprise variable costs (vehicle maintenance and fuel), the decline could reflect a reduction in hours, as well as the decline in fuel prices that occurred during this period. The fact that earnings declined more than costs, however, suggests that effective wages also fell.

How does the press treat this basic story line? The Journal relegated the study to its Real Time Economics section and tried to depict it as the natural workings of the market, and therefore not much to see here. In fairness. the lead author of the report took a much less measured line in interviews than in the report. From the article When the Supply of Uber and Lyft Drivers Rises, Their Earnings Fall:

It’s a classic case of your Econ 101 class being right.

“When you increase the supply of something, you drive down the price,” said Diana Farrell, chief executive of the institute, the research arm of the banking giant.

Uber and Lyft also claim that the fall in average hours per driver is due to drivers choosing to drive fewer hours during peak demand periods. From the Journal:

Similarly, Lyft said its drivers are most concerned with how much they make per hour, not per month. Having more drivers working fewer hours has helped push down average monthly earnings, the company said.

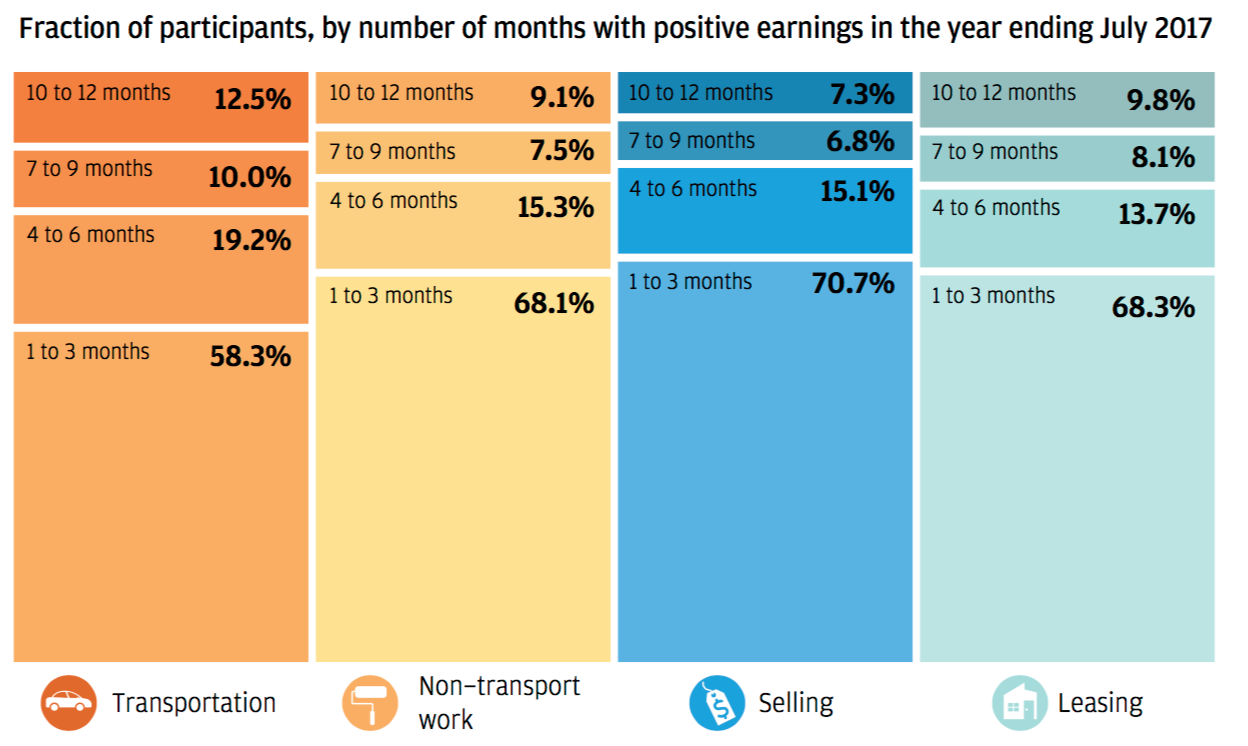

The implication is that these drivers are established drivers who decide to focus on the most lucrative times. But that’s hard to square with this chart, that shows that nearly 60% of ride-share drivers had earnings only one to three months of the year:

As Hubert Horan pointed out:

Since Uber is far and away the biggest company in their sample, the data directionally supports other anecdotal evidence about flattening Uber growth and other less anecdotal evidence about drivers getting a smaller and smaller piece of total fares.

The report talks about how typical gig providers in transportation are only active a few months a year, but didn’t track individuals over time. My strong sense is that most of this is just the horrible turnover you get when people realize how awful the job and pay are, and not people who drive for a while, go on to do something else, but come back to driving multiple times a year. There’s absolutely nothing in the report supporting the Uber/Lyft claim that the declining wages reflects people only driving a few hours a week at peak demand times.

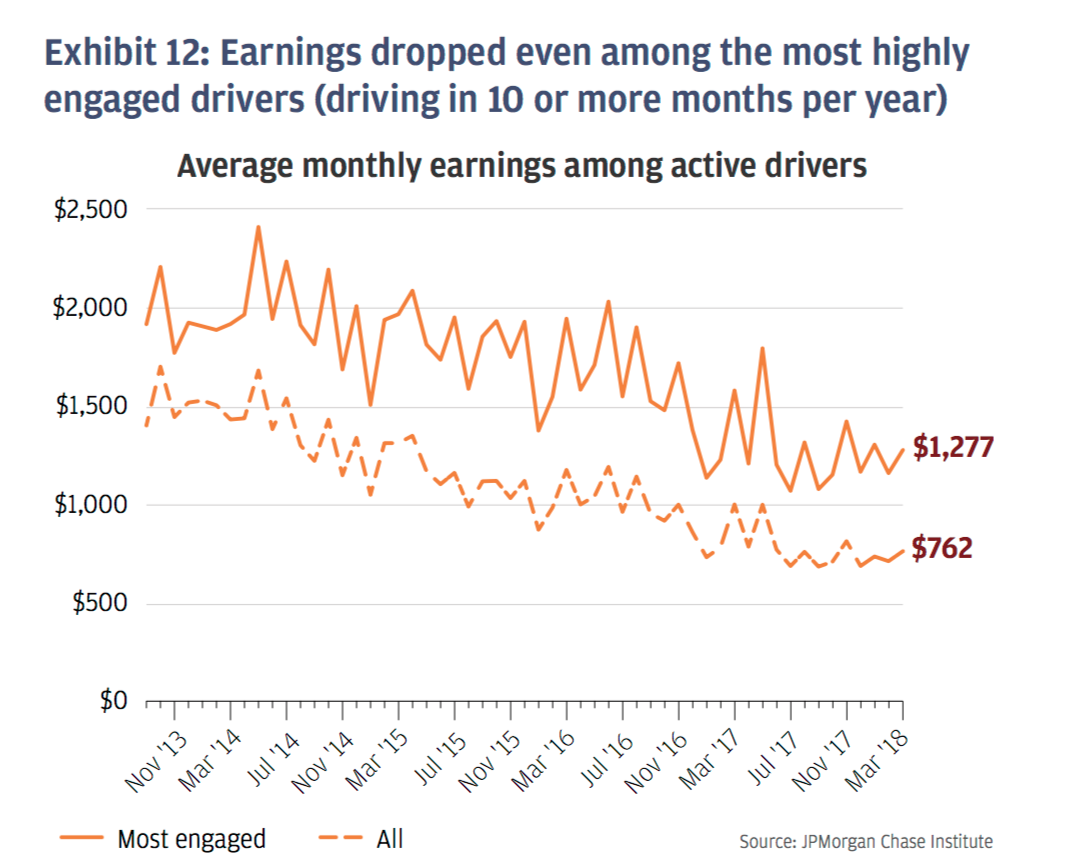

And Hubert flagged a big reason for rising driver churn: their net take has been falling:

One driver issue that I haven’t seen mentioned anywhere is that drivers have effectively been suffering from two separate pay cuts. The first, documented in the P&L data, is Uber’s unilaterally giving drivers a smaller share of gross fare revenue. The second is that drivers bear the full burden of higher fuel costs. fares need to cover total Uber+driver costs; Uber hasn’t been indexing fares to reflect rising gas prices. As opposed to regulated taxis in most cities, where fares were regularly increased (with a time lag) as fuel prices increased.

Since the worker-exploiting Ubers and Lyfts are popular (who wouldn’t want to take a heavily subsidized ride?), both the tech and the general business press has been far too willing to buy their spin, save for salacious personnel scandals. We’ll see if the halo survives Uber’s efforts to go public in 2019, or make excuses as to why it didn’t.

Superb. A fine skewering.

Perhaps companies like Uber are subject to the laws of diminishing returns. As word spreads about the true costs of being an Uber/Lyft driver, fewer people are willing to sign up for it unless they feel that they have to due to economic necessity. Cutting their pay twice merely reinforced for a lot of people what a bad deal it was.

I wonder what those pay cuts were for? Maybe those companies had cash flow problems and use the money saved to plug the gaps. You would hate to think that those companies did so for either larger bonuses for the executives or bigger payouts for the shareholders. Very short-sighted if so.

I drove a taxi for 16 years in my younger days, still one of the best jobs I ever had.

I have a couple of observations that can help illuminate the situation;

It takes some time, likely about six months to a year to learn how to make money in this space, and to allow a person to assess their experience as concerns profitability.

The churn observed in Uber’s drivers can be explained by the fact that it takes a while for drivers to understand that they are not getting ahead over time, but slowly falling behind if they treat their Uber involvement as their only job.

So many Uber drivers last six months or a year, discover that it’s not what they were promised, and quit.

The one benefit of driving for Uber, and it’s not that great a benefit, is cash flow, IOW, if you need some money today, you can have some money today by getting in the car.

On the whole however, many people, probably most will discover they might have been better off to go to work for MacDonalds.

As the number of people who have experienced working with Uber goes up, word-of-mouth alone should eventually be enough to limit Uber’s ability to attract enough drivers to maintain the illusion of legitimacy.

Uninformed comment*: I wonder how much of the skew is due to teachers? Teh Google says there are 3.2 million teachers in the US. The general impression is that they paint houses all summer, but this looks like a good fit too.

*Yes I hate it as much as anybody else when some anon blog commenter assumes he/she has some insight from reading a couple of paragraphs on something, OTOH you didn’t pay for this *and* HH himself uses the term “my strong sense” which means he has no data either….

Chris,

There is ample evidence that Uber and its ilk are not a ‘good fit’ for anyone, and Naked Capitalism has laid it all out quite clearly over time.

I’d say the cost of vehicle depreciation, born by the driver, is enough to prove that driving for Uber amounts to turning your vehicle into an ATM.

Vehicle depreciation is never mentioned in Uber’s pitch to drivers, in fact Uber’s foray into financing of driver’s cars was abandoned, most likely because it was one way in which the issue would have surfaced over time, and they wished to distance themselves from the negative press it would have inevitably brought as thousands of Uber-financed drivers found themselves burdened with cars they couldn’t sell because they had too many miles and they owed more than the cars were worth.

Uber is a scam upfront, and it will not improve your life other than teaching you another hard-knock lesson.

Yves Smith’s colleague at Wolfstreet.com, Wolf Richter, described Uber management’s astonishing ignorance of economics with a previous program: “Unlike most multi-year leases that have high fees for early termination, drivers who participate in Xchange for at least 30 days will be able to return the car with only two weeks notice, and limited additional costs. The program allows for unlimited mileage and the option to lease a used car, with routine maintenance also included.”

https://wolfstreet.com/2017/08/09/uber-gets-run-over-by-its-own-subprime-auto-leases/

Yes, that is also a big ‘tell’ about the nature of the whole Uber scam, they seem to be interested more in appearances, than any else, that being to make Uber attractive at the point of an IPO.

There were a number of mistakes buried in their failed venture into vehicle finance, and most of them could have been avoided if they were serious about doing business as opposed to running a scam.

There is a reason why most taxis are retired police cars, and not new vehicles with financing involved.

One of the other ‘tells’ was the fact that they were not doing any simulation in relation to their supposed Autonomous Vehicle project. everyone else in the AV universe was doing simulation, it finds the problems that should be addressed before hitting the streets.

It adds credence to the impression that they are primarily looking to the big payday of an IPO and not really serious about revolutionizing transportation.

Actually, Naked Capitalism sometimes posts articles by Wolf Richter, but we are an independent blog, and it isn’t accurate to call Richter “Yves Smith’s colleague at Wolfstreet.com.”

I was a ride-hail driver during grad school.

1. “earnings” = gross revenue, not profit. self-evident to the people here, seemingly not to the average journalist.

2. 2013-14 were the golden years to be an Uber-Lyft driver. Rates were higher back then. And MOST IMPORTANTLY, Uber and Lyft (and extinct Sidecar) were throwing shareholder cash at drivers to make cars available/grab market share. One living in a major drinking-eating city could easily gross revenue $500+ in one weekend.

3. Driver supply was more limited and as passengers were conditioned on taxis, the novelty of door-to-door journeys made people happy. happy riders = more tips.

4. I think that there is a quiet despair on in the US non-upper class. Lots of people are looking for extra income, even if it means destroying their car aka depreciation.

For most drivers profit = revenue – gas, when it’s really revenue – gas – depreciation – odds of car crash/injury/death

This sounds condescending—Uber-Lyft are exploiting people’s bad math skills and desperation. Uber and Lyft are equally morally bankrupt companies, just that Uber is the one with the worse PR reputation.

Ask the average person to explain deprecation, they’ll stare right back at you. I regularly see cars used as Uber-Lyft cars that I absolutely know cannot be profitable once you factor in depreciation.

It’s ethically wrong, but it is what it is. So if you ever take a Uber-Lyft, tip generously. It’ll probably be greatly appreciated.

rant over. thanks.

Aw, Leopold, don’t stop now. It’s such a good rant. Keep going for as long as you want.

PS, don’t get me started on Uber-Lyft’s “instant pay” Uber-Lyft have literally entered the pay-day loan business.

Need cash literally today? Give a ride. For *only* a $0.50 ‘convenience fee’ you get your revenue direct deposited that day, as long as Fedwire is open.

So $0.50 out of (say) $80.00. That’s 0.6% interest for one week’s worth of no default, guaranteed pay-day lending. Or annualized, it’s a 38%. Take about bank millions by just scooping up quarters.

dunno what’s worse, people letting themselves get ripped off like that (and happy about it as they get paid that day) or companies that do it when they could easily adjust their cash flow to have more pay periods per week.

both i guess. it is what it is.

That’s fascinating, I had no idea they were doing that. Thanks Leopold.

I wonder how much of this is also from competition due to other models of transport like the e-bike and scooter startups that, anecdotally, are eating up some of the things that an uber might have been used for in the past (e.g. a ride to happy hour).

e-bikes and scooters are considered vehicles in California. Ride one home from Happy Hour and you risk a DUI. The penalty is the same.

is the risk of being stopped the same?

One interesting anecdote re vehicle depreciation:

My mom visits us (immigrants) here in south Chicago every two years and stays for the three summer months. In 2014 and 2016, she was very impressed with how clean and upscale the lyft cars used to be, preferring them over cabs. This summer, it has all been about how uncomfortable the cars feel, and how she’d much rather be taking cabs, even if the wait for one here can be up to 15 mins.

While this has been commented on everywhere these days, we tend to ignore it. But to my mother, this crapification is clear. I think this is indicative of the early adopters picking up better jobs, and maybe of the increasing desperation of remaining uber/lyft drivers.

My buddy started driving for Lyft after getting laid off from his IT job and not being able to find another one. Seems nobody wants to pay an experienced 50+ year old white male when there are desperate college grads and H-1Bs who will work on the cheap, but that’s another story.

He started driving pretty much full time but quickly realized his hourly rate was crap. Then he drove just during peak hours when fares were higher, but he found that the algorithm would often have drivers chasing all over town to get the peak rates – one neighborhood would suddenly go to peak rates, the drivers would all flock there, and suddenly peak didn’t apply any more. Now he only turns on the app when he drives to the gym and only picks up people on his way. If someone gets in, the $3 fare pays for his gas. That’s about all he uses it for these days – he realized a long time ago there was no way to make a living at it.

I’ve been a driver for 3.5 years and have some insights to add. First, uber driving is only profitable in markets where you are paid $1 per mile or more and you have a reliable fuel efficient vehicle. I happen to live in one of those markets. Also, the relevant metric is how much you earn per MILE, not per hour.

As to why earnings are falling, this is because both companies have been suppressing the “surge” pricing (also called prime time on lyft). The smart and profitable drivers would do their homework and learn what events are happening in town. Then, you position yourself near that event and wait until the surge happens. Once it reaches a level high enough, you go online and only take rides that have a surge multiplier attached to the request.

Now, the surges are so rare or so suppressed that you can’t make as much money. The “unicorn” rides as we call them are fewer and farther between (usually a ride that nets you $100 or more b/c of a high surge factor and long distance).

The important point here is that drivers would need those surge rides to help offset the really crappy other rides (fat idiots requesting rides for all of three blocks….it happens all the time).

Another related factor are some new incentive schemes that both companies are using. During periods of high demand (evening rush hour), instead of letting surge pricing kick in, uber is now using a “consecutive trip” bonus. The driver must accept three rides in a row, regardless of ride type or the rating of the passenger, and they will get a small $ bonus (usually between $5-$10). This is where their 96% driver turn over rate is actually an asset. Stupid new drivers have no idea how surge used to work or how prolific it was. these new drivers fall right into uber’s hands. they take pool rides at base rates during the middle of rush hour trying to chase that stupid consecutive trip bonus, which of course is the stupidest thing you can do.

this is why earnings are falling. b/c there are too many stupid new inexperienced drivers that are happily driving for base rates b/c they can’t do basic math to figure out what a bad deal they have.