We’ve been writing for some time that one of the consequences of the protracted super-low interest rate regime of the post crisis era was to create a world of hurt for savers, particularly long-term savers like pension funds, life insurers and retirees. Even though the widespread underfunding at public pension plans is in many cases due to government officials choosing to underfund them (New Jersey in the early 1990s is the poster child), in many cases, the bigger perp is the losses they took during the crisis, followed by QE lowering long-term interest rates so much that it deprived investor of low-risk income-producing investments. Pension funds and other long-term investors had only poor choices after the crisis: take a lot of risk and not be adequately rewarded for it (as we have shown to be the case with private equity).

And as we’ve also pointed out, if you think public pension plans are having a rough time, imagine what it is like for ordinary people (actually, most of you don’t have to imagine). It is very hard to put money aside, given rising medical and housing costs. Unemployment means dipping into savings. And that’s before you get to emergencies: medical, a child who gets in legal trouble, a car becoming a lemon prematurely. And even if you are able to be a disciplined saver, you also need to stick to an asset allocation formula. For those who deeply distrust stocks, it’s hard to put 60% in an equity index fund (one wealthy person I know pays a financial planner 50 basis points a year just to put his money into Vanguard funds because he can’t stand to pull the trigger).

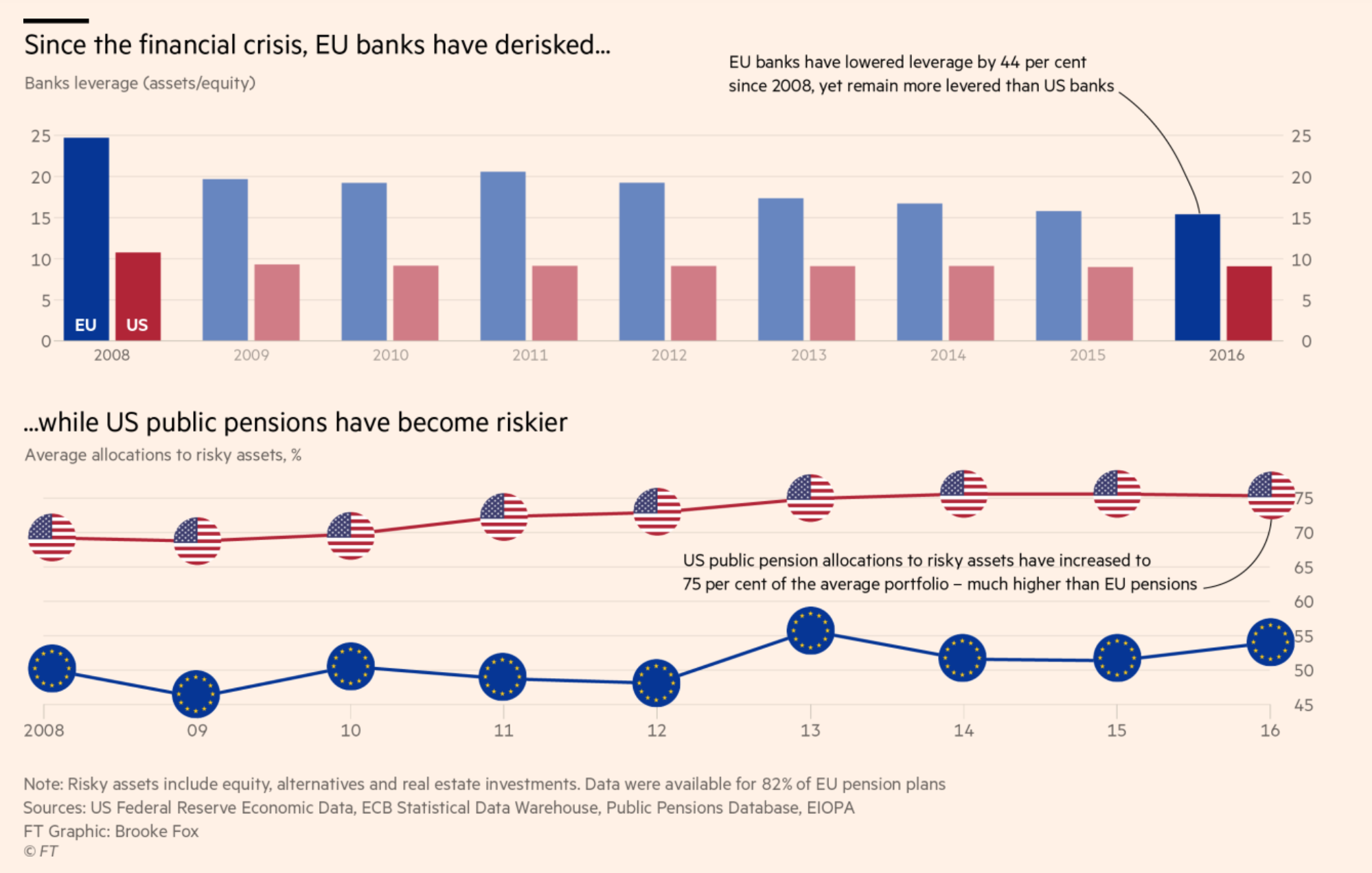

The Financial Times turns to this topic today with a solid piece, Legacy of Lehman Brothers is a global pensions mess, that includes useful data. As many others have, we’ve pointed out that one of the effects of the post-crisis regime was to move risks out of the banking system and into the hands of savers. As the pink paper describes it:

Pension funds have taken on many of the risks that were once held by banks. Low bond yields, which make it more expensive to guarantee an income, have forced them to take extra risks. They now hold assets, such as hedge fund and private equity investments, with much concealed leverage. And many companies have transferred the risk of bad investment performance from their shareholders to savers – and savers are not usually well-equipped to deal with them.

The result: the risk of a sudden banking collapse, which almost happened 10 years ago, has reduced. But the risk of social crisis, as people enter retirement without enough money, is rising.

And betting wrong can make a big difference:

All the central bank activity spurred widely varying returns on assets around the world. US stock markets enjoyed arguably their longest bull market on record. Real assets, such as real estate (which benefits from low interest rates), have also fared well.

But markets outside the US fared far worse, burdened by worries about China, and by the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, which was followed by a severe economic slowdown. While the S&P 500 gained 175 per cent after Lehman fell, stocks in the rest of the world gained only 55 per cent, equivalent to a nominal annual return of barely 4 per cent.

Recall that we’ve pointed out how CalPERS’ returns have lagged those of other large public pension funds, and in particular, those of CalSTRS. One of the big reasons is that its peers have a much lower allocation to foreign stocks. I would assume their aim is to be in more asset classes to reduce risk, while as CalPERS’ consultant Wilshire recounted yesterday, CalPERS objective is to participate in global growth. That hasn’t been working out all that well.

Back to the Financial Times:

The key insight is this: the biggest factor determining a return on your asset in the future is the price you pay for it now. If it is expensive when you buy it, your likely return is lower than if you buy it cheap.

Again from the pink paper:

Abandoning DB [defined benefit] plans reduces the risk that companies will face bills that they cannot pay. But it opens the greater risk that individual savers, far less sophisticated than the actuaries who run company pension plans, will fail to save enough for retirement – particularly as many suffer stagnating wages and have difficulty meeting their current commitments.

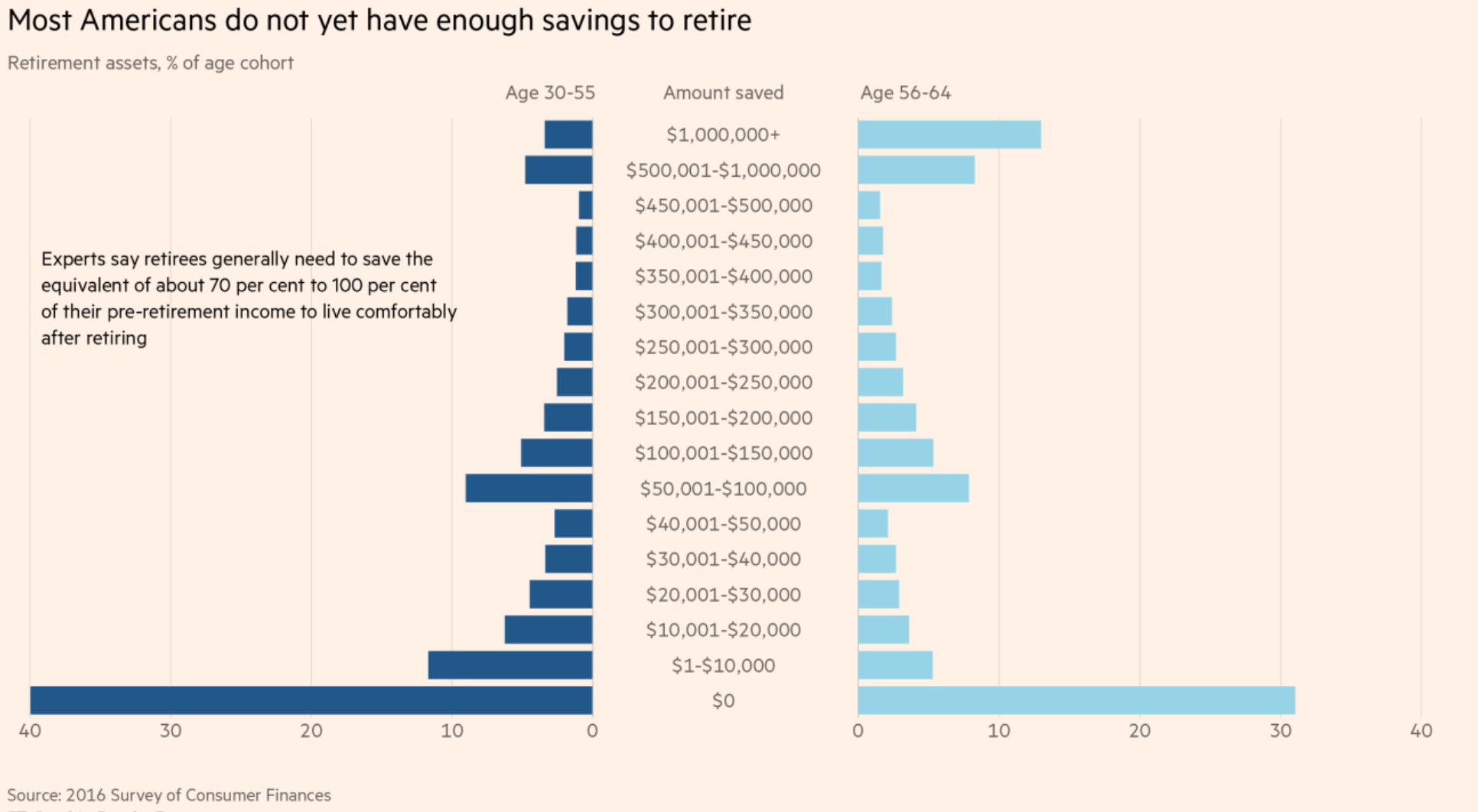

The evidence from the US is alarming…. Most Americans with DC [defined contribution] plans do not have anything like enough money saved to support them in retirement….

If you want a decent chance of an income of two-thirds of your final salary for the rest of your life, you will need a retirement fund worth more than 10 times that final salary. Only a tiny proportion of Americans are on course for achieving this.

The article drily notes that countries that are introducing defined contribution plans should not expect them to fare better than they have in the US. I wonder how Australia’s superannuation scheme, which had just been put in place when I was there, is doing. It initially required workers to put 9% of their pay in a superannuation fund, and I believe is now 9.5% Employees get tax breaks if they make additional voluntary contributions. “Super” gave me the willies because it looked like there were way too many paid advisors and fund fees in the system.

This picture makes clear why so many Americans are interested in moving to lower-cost countries when they retire, particularly given the horrible costs of American healthcare. And don’t think Medicare is a magic bullet. A friend was hit with a $25,000 bill for her stay in a rehab facility after a bad leg break. But the flip side is a quite a few people uproot themselves, only to wind up coming back to the US because they find themselves unable to adapt to a new country. So there are no easy answers, individually and collectively.

The West is always getting fooled by its own bankers.

The banker’s curse.

They can create money, but it has no intrinsic value.

The bankers always want to be more than they are, but they can only create real wealth by lending into business and industry. They should only ever be servants of the real economy.

Governments can create money as well, and when they create too much you get hyperinflation. We all know how you can create money to drive up prices and that the wheelbarrows of money in Weimar Germany had almost no value.

The FED did the same with their “wealth effect” and created money to drive up financial asset prices.

They are effectively the same, but no one seems to realise that driving up financial asset prices is about as useful as hyperinflation.

What is real wealth?

In the 1930s, they pondered over where all that wealth had gone to in 1929 and realised inflating asset prices doesn’t create real wealth, they came up with the GDP measure to track real wealth creation in the economy.

The transfer of existing assets, like stocks and real estate, doesn’t create real wealth and therefore does not add to GDP.

The real wealth in the economy is measured by GDP.

Inflated asset prices aren’t real wealth, and this can disappear almost over-night, as it did in 1929 and 2008.

The Emperor has no clothes.

All very true. To add, even if we were all able and willing to set aside the amounts required to fully fund our prospective retirements (at pitifully small interest rates and and enormous amounts of risk), that amounts to money not spent into the current economy, and thus not spurring any kind of potential recovery in the current period, other than that of the bankster and financier cartels, of course. The phrase heads they win, tails we lose come to mind here…

Well distilled. But quite impossible to believe. A private cartel that can create debt to buy its owner-members’ losses and control its country’s money supply without any political oversight would essentially control its government . . . its media, military . . . everything.

Surely not in America. This is a democracy. That would make our government a criminal enterprise. Most of us just refuse to believe our lying eyes.

Displays a fundamental misunderstanding of hyperinflation, which is caused by a collapse in production rather than excess money creation. The money creation follows (i.e. a result not a cause) as an impossible attempt to adjust to shortages by creating more money (or re-denominating money) to buy what doesn’t exist, driving prices up further.

Like a cat chasing it’s own tail.

If a country such as the US were to experience some event that drastically reduced the supply of essential resources, like food, energy, etc. hyperinflation could and likely would occur without the government creating a single extra dollar.

Regarding super in Australia, surprise, surprise

Can’t remember where it was, but I saw a good article that argued it was the fact that companies were forced to bring the pensions on their balance sheet that caused a lot of DB pensions to die – as technically, DB cannot be ever properly de-risked and financed.

But that DB was a risk-sharing of the employee with the company, and that it actually meant the employee had interest in the company’s long-and-successful life.

Yes, more so than the management.

Employees have their ill-liquid lives invested in their employer, shareholders only have some of their very liquid investment at risk.

Who is taking the bigger risk?

A defined benefit plan most certainly can be taken off balance sheet, but it’s pricey. It’s called defeasement. You have to fund all the expected liabilities with Treasuries.

I understand this as a theoretical requirement, but why is it a practical one?

Once you set an expected rate of return, you have a number. Why is it not credible to immediately issue corporate bonds or even stock to the pension fund, sufficient to meet your expected rate of return?

I get why management is highly motivated to lie about what a sane rate of return is. But again, there is some number that makes a defined benefit plan sane and likely to succeed.

ah, it was a sidenote to https://www.johnkay.com/2018/09/06/uss-crisis-can-the-pension-system-be-reformed/

What are the markets telling us?

Low returns on investment capital – There is an excess of investment capital.

Low inflation – Insufficient demand

The markets are calling for some redistribution of wealth.

The people at the top have too much to invest and those at the bottom don’t have enough to spend.

Ignore the markets.

You nailed it, Sound. I happened to be watching CNBC when Rick Santelli had his two most famous rants: the first was when he called for creation of a ‘new Tea Party’–that astroturf ‘movement’ started soon after (aided and abetted by the Koch brothers, IIRC)–and when he was ranting that the Fed, by lowering interest rates, was going to ‘debase’ the dollar. Well, the dollar is strong, too strong by some accounts, and inflation–at least, the officially rigged number–is arguably too low. We all know what the Tea Party has wrought (hint: it’s orange).

I only have a couple semesters of lower division econ, but it’s been apparent to me that inflation is only caused by increased demand; i.e. price elasticity and all that. The pent up demand appears to be mostly going on credit cards.

On this 10 year anniversary of the Great Recession – I was also remembering Rick Santelli – the ALWAYS SMILING trading floor CNBC guy… with his angry rant at the people who took out mortgages they could not afford.

After that: I could never think of CNBC again without some measure of disgust .

The day of reckoning is fast approaching for state pension funds. Place your bets on the first to fall. Will it be California, Illinois, NJ or Ct? The last 4 puppets in the WH have done a fantastic job of destroying America on behalf of their globalist masters. Let the Hunger Games begin.

I think it’s gonna be Connecticut. A lot of the Democratic political power here lies with people in Fairfield County whose financial well-being (and identity) is actually more tied to New York than the state they live in, so they will be able to viscerally rationalize letting the pension system fail instead of bolstering it with tax dollars the way New York did. Meanwhile, plenty of outsiders will applaud them because they’re “setting an example” for other, more important pension funds to be more responsible, and hey, “Connecticut is a rich state, those people can probably afford it, I’m sure someone will help them somehow … if they even need help, those overpaid a-holes.” (Connecticut is basically the capital of income/wealth inequality, of course. Hedge fund central.) Connecticut Republicans are probably on board already, as their anti-state mentality has been percolating for decades. Recent pension fund returns have been slightly low compared to other states, too.

My guess is there will be no or virtually no pensions for people born during/after 1967 who thought they would be able to take retirement in 2023, 2026, 2029, 2032, 2035, ever. The federal government will allow it to happen, too. This is my near future as I scrape by in the gig economy on $10K a year – I expect it to be formally announced in 2021 or 2022 when the collective bargaining agreement is renegotiated, the year prior to when I was supposed to be pension-eligible (my state job essentially got phased out by the financial crisis in ’08, so sticking around longer isn’t an actual option). Joke’s on me. Wish I could go back to the early 1990’s and ignore the people who told me, “Hey, a state job may pay less than a private firm, but it’s safe and you earn a pension that will provide security when you get old.” The truth is, the financial industry took that future away because it could, and Americans have been brainwashed en masse to look askance at state employees anyway, so they’re disinclined to create political pressure that would be helpful.

I try to be an optimist….but throw in broke, angry seniors into the toxic stew of today’s Left-Right identity politics….I think that the next 20 years are going to make the 2016 – 2018 look like a golden age of civility

20 years of asset stripping… Three Bubbles & A Funeral? Funny how it coincided with overturning the Glass-Steagall Act. Why, one might almost think it was premeditated.

Cause or effect?

Elite asset-hoarding in response to the global population crisis isn’t discussed anywhere, treating their use of the political apparatus to facilitate the looting of everybody else’s savings like it’s the weather. Tax-cuts, bail-outs, and rate-cuts are some of the redistributive political choices dictated by elites. There have been others.

Today, 25 September 2018, the World Population Clock happens to have passed the threshold when we can start rounding UP to 7.7 Billion human beings on the planet. A more even distribution of our more or less finite planetary resources would mean sacrifices that elites are unwilling to make, so instead they have accelerated redistribution in the opposite direction — hoarding everything that they can get their hands on.

The pension train wreck was going off the rails before the GFC.

The article indicates that by identifying the intentional “underfunding” of pension plans (mostly state and municipal). States and cities that don’t provide their share of timely funding to a pension plan essentially reduce the pension plans’s earning potential. (The Time Value of money is real.)

Yes but zero interest rates turned a manageable problem into an unmanageable problem.

Aka: Assuming a 7% rate of return on pension fund assets, and funds management becoming desperate, which leads to believing in the snake oil of the private equity crowd.

That second chart is interesting…almost fractal. Anybody have any ideas about why it’s got those “waves” in it? Why the big spikes at $50,001 and $500,001? What’s that all about?

The spikes are big in the chart at $500001 and $500001 because those particular bars cover a 2-to-1 ratio of retirement assets, whereas the other bars cover a smaller ratio and therefore cover fewer people.

A more logical scheme would have been to use a bars that were logarithmically spaced, or nearly so. Like this:

0 to 1,600

1,601 to 2,500

2,501 to 4,000

4,001 to 6,300

6,301 to 10,000

10,001 to 16,000

16,001 to 25,000

25,001 to 40,000

40,001 to 63,000

63,001 to 100,000

100,001 to 160,000

160,001 to 250,000

250,001 to 400,000

400,001 to 630,000

630,001 to 1,000,000

1,000,001+

Here, each band would cover a ratio of retirement assets of approximately 1.58-to-1. The funny spikes would disappear, but the predominance of retirement accounts with pitifully small balances would still be evident.

The big chart spikes are where the savings increment changes, from $10,000 to $50,000, or from $50,000 to $500,000. The chart is not strictly arithmetic. It’s a confusing representation, IMO.

the “buckets” at those surge points are much larger than the ones immediately below them. The surge you see at the $50,001 level is because it covers the $50k-100k range but the bucket below only covers the $40k-50k range. Similar for the $500,0001 bucket, it has a spread of $500k while the one below it only covers a $50k range.

Suddenly bigger bands means more people get captured in those buckets.

Can someone help me understand the 3rd plot? It seems to be suggesting that over 10% of the age cohort 55-65 has 1 million + worth of assets. Isn’t that a ludicrously high estimate? I must be reading this chart incorrectly.

No. That age cohort no longer has defined benefit pensions by and large. Or only small ones. I.e. the wife was a teacher, while the husband drew down more most years….. in less steady corporate jobs that only offered 401(k)s. When you are that close to retirement, a net worth of ~$1,000,000 is frankly a prerequisite for a decent life through age ~80-85. Remember, it’s estimated that average end-of-life medical costs for middle class Americans are in the 6 figures now. They also need to eat, and they need to heat and cool their houses. The problem is that too few of us have anywhere near that much saved, not that 10% have achieved it.

It would be great to see the geographic distribution of this age/wealth cohort. I bet most of the upper 10% are on the coasts, and that most of their “wealth” is locked up in their real estate.

I’m not sure that it’s wildly off base, it’s only ~10-12% of workers aged 56-64, so some ~85-90% of them have less than $1 million saved. While there’s lot of people in that age cohort that have had a difficult saving over their working lives, it’s not unreasonable to expect that some meaningful number of people were able to save consistently and early on in the game so they would experience the power of compounding over time. I would expect that reasons would vary from high earnings, conservative expenses, dual income with no kids, etc.

The cutoff for top 10% income was $133k in 2014. $1 million in home equity and retirement accounts by early 60s for people making this amount of money seems realistic to me. Diligent savers in the 10%-20% range could also very well be there.

A few comments since this post touches on many issues:

1. The worst pension funds simply have not put enough money in under any reasonable actuarial calculation. This is a total dereliction of duty.

2. Since there is a demographic bulge moving through the pension system, I think there is an argument for and a need for using a couple of different returns over different time-series. It is likely that there will be long-term (30 year+) real returns of about 4-5%. The problem is that the likely real return over the next decade is likely to be around 0% which is a serious sequence of returns risk as that will be when there are peak boomer withdrawals. Personally, for my planning that is the returns scenario I am using for my 60/40 portfolio: 0% real for 7-10 years; 4% real after that.

3. Healthcare is a cost, not a payment problem in the US. I have been utterly baffled by the complete inability of the major payers in the system (corporations and governments) to get control of the costs. If the US could reduce the cost by about 1/3 per capita to simply get it to the top range of the rest of the developed world, the “how do we pay for it” issue would largely disappear. To my mind, this is the largest failure of the “free market” in the US since WW II.

4. Every American has been paying 12.4% of their income into Social Security since they were in their teams. This is basically the same as the 10-15% recommended by financial planners for retirement savings. So it is perfectly reasonable to assume that a significant percentage of the retirement income fo the bottom 90% should come from Social Security. There are some actuarial problems with Social Security but it is run at a very low cost. The low interest rates have hit it since the Trust Fund is invested in Treasuries.

5. The 10x income number required for retirement savings is essentially for the top 10%. Social Security covers a higher and higher percentage of income as income declines. Down around $40-60k income, the savings need to get 2/3+ of pre-retirement income is only about 5x, so those $100k+ DC balances don’t look so bad in that context.

6. The average SS income of about $17k/year is that low because many people take it at 62 and because spousal income is limited to 50% of the spouse’s SS at FRA. Two people can generally get over $30k a year of SS if they have had $40k+ of income during their career.

7. The real blood bath is going to be the people who are in effectively insolvent DB pensions that “replaced” Social Security so if their pension goes away, they will not have the SS income to fall back on.

Good comments, I’ll add mine:

1) Agreed. There are lots of factors in play here from abuse of the payout calculations, to administrative bloat, to underfunding, to unrealistic return assumptions, and so on. Ultimately it’s problem created in large part by elected officials overseeing this process.

2) Analysis can be done to determine the likelihood of exhausting pension assets based on a random sequence of returns. Actuaries routinely do this and while the numbers are seldom (if ever) talked about, it’s a known scenario.

3) Agreed, HC costs are the largest single concern for most retirees.

4) Your analysis is a little off here. The withholding rate was not always 12.4% and workers only paid it on a limited portion of their income. Benefits are typically maxed out per individual at around $42k, which probably does not replace a significant percentage of the bottom 90% W2 income (I’m guessing it’s closer to half).

5) There’s always a case-by-case element to this, but you’re probably correct. This is why people are moving into cheaper areas at retirement

6) Yes, but there are plenty of reasons for not waiting to take SS, the most common being: a) can’t afford not to due to limited other sources of savings/income in retirement, and b) shorter life expectancy such that taking earlier actually maximizes the draw from the system.

7) This is the crisis, in a nutshell. While not all pensions will go away, some will see benefits severely cut. It will be ugly, yes.

Re: No. 4

The 90% threshold was $133 in 2014. Two-thirds of that is $88k (say $90k today). A maximum Social Security benefit of $36k at FRA and about $45k if you wait to 70. so if you wait to 70, SS benefit is about 1/3 of the gross pre-retirement income which I think is significant as no pension or savings are tapped yet.

The progressive nature is because in 2017 $, the benefits are calculated using 90% of the first $10,740, 32% of the next $54,024, and 15% of the remaining income to the max of $127,200 income. Previous income is adjusted for inflation so $1 in in 1984 is worth $3 in today’s calculation. The best 35 years are averaged, so those teen years go away if a full career of 35+ years from mid-20s to early 60s is worked.

So if somebody had the equivalent of $20k per year for 35 years, then they would receive $12,629/year at FRA adjusting for inflation or 63% of pre-retirement income, so just about at 2/3 with no savings.

At $64,764 pre-retirement income, they would receive $26,954/year at FRA or 42% of pre-retirement income, also increasing with inflation over time. An additional $15,790 per year of income would need to be generated to get to 2/3 of the $64,764 income which would be about $394k of savings required, or about 6 times annual income assuming about 4% per year of income, inflation adjusting over time.

Pretty much anything on a W2 is classified as income subject to FICA taxes up to the maximum ($127,200 in 2017). Basically, you have to have passive income from capital gains, interest, etc. to avoid FICA on declared income.

Re: No. 6

A couple with one wage earner with the maximum benefit can get $63k per year at age 70 if they wait to have the primary wage earner take SS at 70 while the spouse takes the spousal benefit at FRA. While that requires waiting to take SS until 70 for the older spouse and 66-67 for the spouse, that strategy would provide about 50% of the pre-retirement income, which would be a significant income source.

Basically, Social Security is a significant source of retirement income for people who had salary and wages at or below the maximum subject to the Social Security withholdings. That is about 90% of the population. On the whole, Social Security is a government run insurance annuity program with a disability rider.

Central control of prices is at work.

Commercial Real Estate (Retail) is being killed by Amazon. I’ve two large investors who are bailing out of Retail after aI made a simple statement “Amazon is killing Retail.”

Housing is in a bubble: Ability to pay is the lower of 31% of Income or 43% of all debt payments. If the home loan payment is lower than these thresholds, then the price of home rises until its at the threshold or 31% or 43%.

The housing market is no market, it is controlled by the “affordability” of housing, which in turn is governed by the debt to income ratios above.

Housing is also a very ill-liquid market, the cost of bruin and selling a home in the US is approximately 10% of the selling home’s price, and is a huge hit on the equity of the selling home.

The conclusion is the Fed, through interest rates, controls price in the housing market.

very good posting, and very good issues raised. thank you.

And that phrase right there is the crux of the problem. Why should it be that two people work for about the same number of years for the same salary, but one person or their pension fund makes a bad bet and retires a pauper (or simply works until they die) while the one who made a lucky bet spends their golden years in comfort?

Why must we invest at all in order to retire? And why indeed when it’s less and less “investing” and more and more “betting”? Who doesn’t understand that casinos are rigged to favor the house?

To hell with pensions and 401ks that force people with no financial acumen into the financial markets. You have some extra money you want to play with, fine – go to a casino or buy some bitcoin or take a flyer on a tech IPO. But don’t force the rest of us to play along too.

All hail lyman alpha blob! Your final paragraph nails it. Thank you for finishing your comment with a flourish.

Great summary of the crisis, Yves.

I think that the evolution of private equity towards the ownership of Unicorns like Uber is a negative for the little guy. When the public can’t invest in the best technologies, because private equity guys are hoarding it, that’s a bad thing. (Not that I think Uber’s prospects are that great in particular, but there has been a great reduction in the number of companies that go public.)

Thankyou. Meanwhile, the MSM says the financial crisis is over because the tbtf banks and bondholders were saved. Imagine Herbert Hoover (who had many fine accomplishments to his name, including saving Belgium and the low countries from starvation in WWI, but he was out of his depth as president in 1929), imagine him saving the 1929 FIRE sector and then declaring the problem solved. The great depression would have proceeded to devastate the country anyway, no matter what the great said.

If a tree falls in the forest (main street depression) and the MSM doesn’t report it, is it really happening? The politicians owned by the FIRE sector would say ‘no, there’s no depression’.

“The banks, they own this place.” – Sen. Durban on the FIRE sector’s influence in Congress.

adding commentary on 2 pink paper paras (with which I agree):

The evidence from the US is alarming…. Most Americans with DC [defined contribution] plans do not have anything like enough money saved to support them in retirement….

More and more public pension systems are forcing new hires into DC pension plans, whereas earlier hires (hires made 10 years ago and earlier) were included in DB plans as a matter of course.

If you want a decent chance of an income of two-thirds of your final salary for the rest of your life, you will need a retirement fund worth more than 10 times that final salary. Only a tiny proportion of Americans are on course for achieving this.

This assumes a decent savings interest rate of at least 4 to 5 %, imo. So long as the US Fed keeps interest rates artificially low to save the tbtf banks bond holders the interest rates will stay so low they cannot provide a 2/3 final salary income for savers.

This was an obvious implication even before the explicit crisis and bailout hit for anyone with 2 brain cells to rub together. However, the further point is that ZIRP/QE required that retirement/insurance funds as part of “capital markets” would need to “save” all the more to meet future contingent liabilities due to the increased price/lower returns of financial assets effected thereby, thus blunting the ostensibly intended effects of such monetarist policies.

And the more we must save to fund our own retirements the less we can spend now in the real economy. A vicious circle.

It is a sadistic joke of a “healthcare” system that is the problem. Medicare does not provide enough services nor does it reimburse at an adequate amount. So even if there was Medicare for all, we would still have a similar situation as we do with Obamacare.

The slogan “Medicare for All” is a convenient shorthand for explaining how fairly simple it would be to provide coverage for all Americans even if it would be the inadequate Medicare.

I read somewhere that the cost of healthcare in the US is three times that of where I live (Australia)in terms of the proportion of GDP. And ours does not exactly inspire regarding either efficiency, availability, equity or cost. So much for the efficiency of capitalism.

I also read a promo by Keith Fitzgerald re. US retirement funds to the effect that US retirement funds were massively underperforming their financial predictions to the tune of 6 trillion dollars, with benefits paid consequently far less than retired beneficiaries expect, or need. The analogy of a snake swallowing its own tail was used in the description.

CalPERS was claimed as the worst offender, but many other state based funds were not far behind.

Fitzgerald claimed that this situation would precipitate the next financial crisis, supposedly starting the coming halloween.

That would spice up your mid term elections – and would be hard to dismiss as fake news by you know who……

A question about the graphic titled “The Future of Returns Looks Grim”. If I’m not mistaken the five-year averages on the left-hand side are not adjusted for inflation (“nominal returns”) while the predictions on the right-hand side are adjusted for inflation (“real returns”). Is that correct? If so, should the graphic be revised to compare apples to apples or oranges to oranges? Thank you.