This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 923 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser and what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, thanking our guest bloggers.

It takes a lot of doing for a private equity firm to become insolvent, particularly if it has a good track record and is in the middle of raising a new fund. But Abraaj, a Dubai-based fund that was the darling of the Davos set and had attracted the bluest of blue-chip investors like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Overseas Private Investment Corp. The Washington State Investment Board invested in Abraaj funds last year, which given the timetable means not long at all before the firm filed for insolvency.1 Similarly, in a sign of what passes for due diligence in private equity, consultant and supposed expert Hamilton Lane signed off on a $345 million investment last last year, less than nine months before the funds imploded, despite receiving an e-mailed warning about misuse of cash.

As the Wall Street Journal tells the story in an impressively detailed account, Abraaj’s Pakistani founder Arif Naqvi scored early successes in private equity investing. His first important deal, the 1999 purchase of the Middle Eastern grocery and liquor-retailing assets of Inchape, netted a $75.4 million profit on a $4.1 million equity investment. There was a warning of things to come in that Naqvi got in a dispute with his backers over what they should have gotten that was eventually settled out of court.

In 2002, Naqvi founded Abraaj with $116 million from wealthy Middle Eastern families. The fund initially did well, for instance, buying a $505 million interest in Middle Eastern investment bank EFG-Hermes and flipping it in a year for two times as much. Abraaj greatly expanded its network when it bought a London private equity firm, Aureos Capital, that had Western institutional investors as its limited partners.

Naqvi had been wooing elite investors with a pitch that he would make attractive returns while doing good by investing in low-income countries. One of his funds was to invest in city hospitals in Africa and Asia.

In addition to Naqvi networking at Davos and other exclusive social events, Abraaj also hired and engaged top names, such as Obama’s college roomie Wahid Hamid and Kito de Boer, a long-standing McKinsey director who had also served as Tony Blair’s successor as Middle East peace envoy. In 2017, Abraaj hired John Kerry to speak at its annual conference.2

By 2016, Abraaj had raised most of the funds for a $1 billion health care fund. From the Journal:

The fund invested in companies such as Pakistan’s Islamabad Diagnostic Centre and the hospital chain Quality Care India. The fund’s hospitals and clinics employed a total of 3,800 nurses at the start of this year.

Note the investments are sufficiently new that it is not clear whether they were panning out.

While the very detailed story can’t fully connect the dots of how the fund fell apart, there look to be at least two big causes of its cash crunch. One was that the sale of a major asset fell apart due to the Pakistan corruption scandal that engulfed former Prime Minster Nawaz Sharif. Abraaj owned part of K-Electric Ltd., Karachi’s electricity utility. Naqvi offered a $20 million bribe, erm, payment, to Navaid Malik to secure the support of Sharif and his brother for the deal, since the government was part owner and would have to bless any equity sale.

In 2016, Abraaj announced that Shanghai Electric Power Co. would buy its stake for $1.77 billion. But the approval was delayed and the deal was had not been consummated. Based on the timeline, Shariff’s removal as Prime Minister in July 2017 looks to have played a part.

A second contributor was that Naqvi was skimming funds from Abraaj. As the Journal explains:

Abraaj used investor funds for its own expenses, according to former executives and investors. The firm further muddied its finances with the “unusual practice” of borrowing money secured against its own stakes in its funds, creating “a highly unstable business model,” liquidators wrote in a report. Abraaj has defaulted on more than $1 billion of debt.

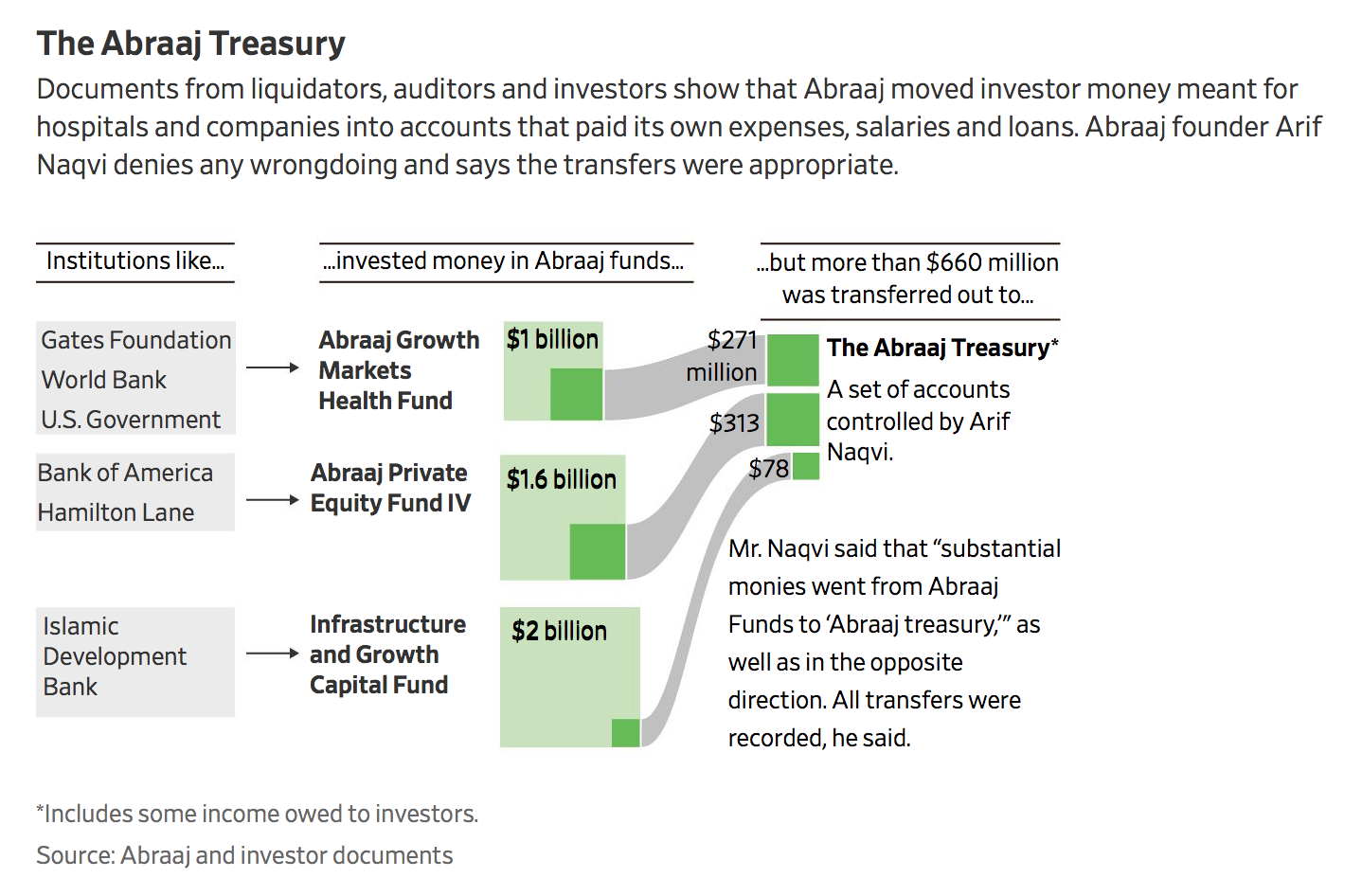

As investigators and investors dig further, more details are emerging that reveal the scope of the problems. At least $660 million of investor money was moved without the knowledge of most investors into bank accounts that forensic accountants call the Abraaj treasury, according to documents and people familiar with the situation.

More than $200 million flowed from those accounts to Mr. Naqvi and people close to him, according to company documents and people familiar with the situation.

In May 2017, after being asked to send payments to one of Mr. Naqvi’s sons and a company run by his former assistant, Abraaj finance executive Rafique Lakhani emailed his concerns about a “cash crunch” to Mr. Naqvi. He wrote: “The tension and stress is unbearable for me and it is affecting my health and my efficiency, and performance at work. I don’t know what else to say.”

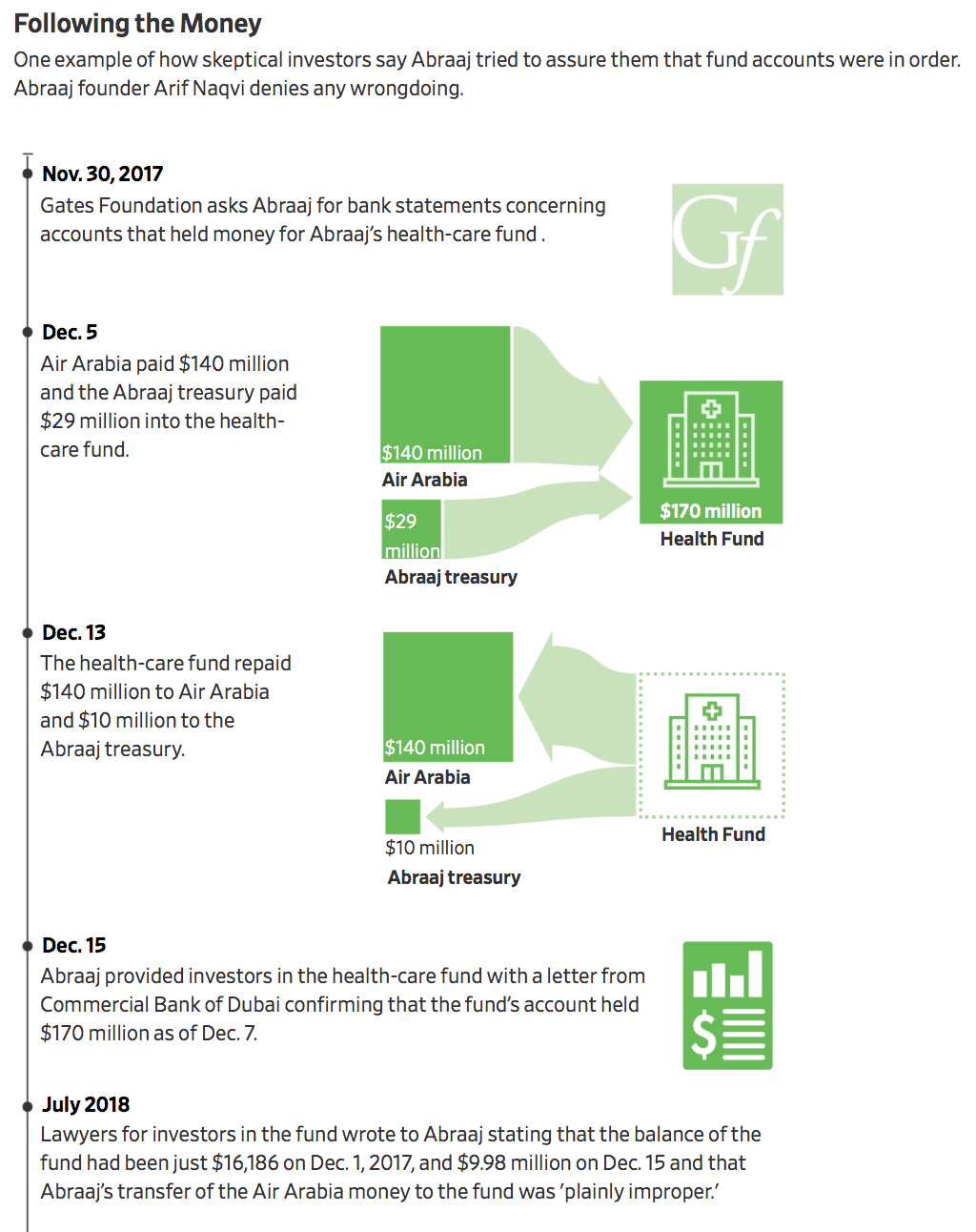

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation was one of the investors that started suspecting something was amiss in 2017:

<

Naqvi of course denies vehemently that he did anything improper.

Oh, and let us not forget the due diligence failure of Hamilton Lane, a firm we’ve caught out treating due diligence as repackaging general partner marketing materials. Again from the Journal:

Hamilton Lane, a Pennsylvania-based firm that advises pension funds and other institutions on more than $400 billion in private-equity investments, persuaded its clients to invest at least $345 million with Abraaj last year—despite receiving an anonymous email on Sept. 23, 2017, urging against investing.

“Cash is used to fund the working capital,” the email said. “Get to the bottom of the Karachi electric story” and “don’t believe the slides and presentations,” it said.

Private equity is all about selling hope, and Abraaj offered a seductive twofer: participating in investing markets, which in theory can deliver great returns but too often leave investors holding the bag, and socially responsible investing, made even more attractive by helping impoverished populations. As this case unfolds, the public will get a better sense of when Naqvi started playing fast and loose with investor monies and when warning signs started appearing. Again from the Journal:

One former employee described Abraaj’s work as “inspirational capitalism at its most enlightened.”…

The collapse has led some investors to question whether Dubai’s regulatory environment is sufficiently safe—and privately, some worry it has damaged trust in the movement to use private capital to solve social problems in emerging markets.

The lesson may be simpler: if something sound too good to be true, it may well be and therefore warrants more inspection. Microlending also had a great following among the Davos set, grew to a $60 billion business that did not get people out of poverty and if anything, increased the amount of suicides in India. Or consider what happened in South Africa, per The Conversation:

South Africa saw a dramatic fall in average incomes in the informal economy – around 11% per year in real terms – from 1997-2003. This was brought about by two things:

- a modest rise in the number of micro enterprises in townships and rural areas driven by greater availability of micro credit, along with

- little additional demand due to the austerity policies of the government.

What then happened was that the self-employment jobs created by the expansion of the informal sector were offset by the fall in average informal sector incomes. Increased competition softened prices and reduced turnover in each microenterprise as existing demand was simply shared out more widely. Poverty inevitably spiked.

The microcredit movement thus helped plunge large numbers of black South African’s into deeper over-indebtedness, poverty and insecurity. At the same time, not coincidentally, a tiny white elite became extremely rich by supplying large amounts of microcredit to black South Africans.

In the meantime, the Wall Street Journal deserves kudos for this impressively researched story. I’m sure the Journal will provide more updates as the insolvency proceedings and related litigation move forward. If you can, do read the article in full for more juicy details.

____

1 Unless Middle Eastern funds run on very different lines than US and European funds, that means the Washington State Investment Board took more reputataional than financial damage. Private equity limited partners make commitments when a fund closes, but send money only when they get capital calls for specific deals. It is thus very probable that the SIB had sent well less than half of its committed capital.

2 The Journal finesses the issue of whether Kerry was paid, but big PE funds routinely pay top dollar for their annual conference “entertainment”. A guy at Kerry’s level would never do a gig like this for free.

Unable to access the WSJ article behind the subscription wall, but a fascinating story that I suspect is likely the tip of the iceberg. While Abraaj is of comparatively modest size related to some other prominent bankruptcies and liquidations over the past couple decades, it causes one to again question who is doing the due diligence, underwriting, and monitoring of outlays of public money; this time at the Overseas Private Investment Corporation and World Bank, as well as at state investment boards, and whether such investments are prima facie consistent with the public policy mandates of those organizations.

Appears to have been organized and operated to deliberately avoid centralized oversight of their operations, with echos of the infamous BCCI in that regard. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that whenever one hears touted the term “Public-Private Partnership”, those with responsibility for the public purse need to run as fast as they can in the opposite direction.

A question in my mind after reading this post is to what extent the limited partners and their investments are insulated from financial and legal difficulties of the general partner, both as a legal and practical matter, and whether another general partner can be appointed?

The article said other private equity funds are looking at picking up the management of the existing funds.

However, let’s say you committed $100 million to an Abraaj fund. Unless they were stealing only from the profit on deals, you are looking at losing money. As this progresses, we’ll know better what the losses were on each fund.

It constantly boggles my mind that supposedly savvy investors seem to be so often caught flat footed regarding how the investment funds are managed. Are we to suppose that the Gates foundation doesn’t have access to it’s pick of investments or the ability to employ it’s own on the ground eyes and ears to protect large investments in emerging markets. It seems all to easy to buy credibility as long as you have enough money. Oh, John Kerry spoke at their annual meeting, must be a good bet!

what besides political connections does John Kerry bring to the party?

These guys are mentioned in the “Billion Dollar Whale” book on Malaysia’s 1MDB scandal, just released (and highly recommended, if you can stomach it).

Whales of a feather….

(extending remarks)

…. diversion of funder (Gates!) monies to private accounts of fund manager, check

…. which are then used in desperate attempts to ‘facilitate’ exit from ill-advised EM investments, check

…. which in this case happens to be the Karachi utility! In the name of Mohammed (pbuh) what were they thinking!!!?

https://herald.dawn.com/news/1398660

…. cuz fund manager “turnarounds” are pretty much 100% Gordon Gekko chop and flog financial engineering, plus a little (overdue) capex and outsourcing to grease the joints, check.

… Resulting in labor strife and massive political pushback (and shakedowns), check.

From October 2008 to October 2016, the company claimed to have added over 1,000 megawatts of additional generation capacity and caused transmission and distribution losses to drop by 12 percentage points. Its biggest boast was that in 2012, four years into its acquisition, the company recorded its first net positive (EBITDA) in 17 years. In the financial year 2011-2012, it recorded EBITDA of 3.5 billion rupees. In its latest financial results for the year 2016, EBITDA was at 44 billion rupees.

In the nearly ten years that K-Electric spent under the Abraaj management, it saw two chief executive officers come and go, riots led by labour unions engulf its head office and found itself battling government intransigence on multiple fronts.

The provincial government of Sindh and its various offices and entities were its biggest consumers and defaulters, the state-owned gas company had a long-running feud with it on gas supplies, the power sector regulator repeatedly refused its requests for tariff hikes and the federal government struggled to build consensus for approval of its eventual sale or to intervene in its numerous run-ins with government entities.

… Along the way it also had to abandon its Plan A for divestment that involved unbundling the vertically integrated utility and selling off its generation, transmission and distribution assets separately. That plan was stonewalled by the regulator which refused to unbundle K-Electric’s licence, which only allows for an integrated power utility. So Abraaj Capital fell back on Plan B: sell the entire entity as an integrated proposition to a strategic investor. It took at least two years to find that strategic investor in the form of Shanghai Power…. For two years, Abraaj Capital battled with the government to get the relevant approvals while the K-Electric management pleaded with the regulator for the right tariff at which a deal worth 1.77 billion US dollars could be closed.

But as liquidators and creditors now move in to organise a firesale of Abraaj Capital assets to pay off the private equity firm’s more than a billion dollars in debts, time could be running out for the sale to go through, at least at the price hoped for.

Nice work there, O Masters of the Darul Islamic Universe. Were you thinking that hey, the locals will roll over for a Sunni bro and let you walk away with a giant payday off their infra?

Bud Foxx, to the white courtesy phone….