Yves here. Note we are publishing this piece because it describes what the European Commission could do to discipline Italy if it refused to back down in its challenge to budget rules. The idea that a country with slack resources, mired in a slow-motion depression, should be running a fiscal surplus is absurd.

Also apologies for the awkward rendering of the very informative chart on the steps in a sanction process. It might be easier to read the smaller version in the original post.

By Grégory Claeys, an Associate Professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris, and Antoine Mathieu Collin, a Research Assistant at Bruegel. Originally published at Bruegel

The Italian government has announced an increase of its deficit for 2019, breaking the commitment from the previous government to decrease it to 0.8% next year. This blog post explores the options for the European Commission and the procedures prescribed by the European fiscal framework in this case.

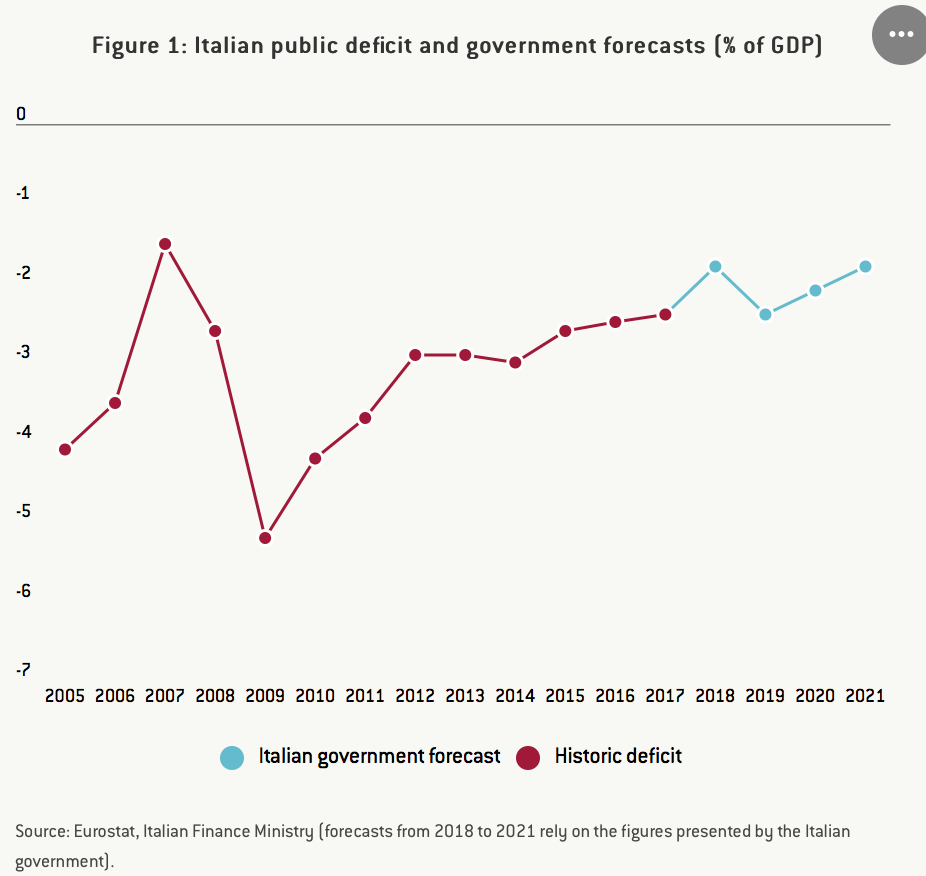

On September 27th, Italy’s ruling coalition surprised markets and its European partners when it announced its plan to increase the Italian public deficit to 2.4% of GDP in 2019, even though the previous government had promised a decline of the deficit to 0.8% for that same year. Moreover, this first announcement foresaw a 2.4% deficit in 2020 and 2021 too.

The pressure from the European Commission and its European partners, as well as the strong reaction from the bond market, forced the government to partially reconsider its plans. On October 4th, Prime Minister Conte announced that the government had amended its plan and that, although the deficit would still reach 2.4% in 2019, it would be reduced to 2.1% of GDP in 2020, and to 1.8% in 2021 (see Figure 1).

Also on October 4th, the government revealed the details of its budget plan in its ‘economic and financial document’ for 2019, as well as in a letter to the European Commission. As expected, these documents show that the deficit increase is intended to finance the tax cuts promised by the League, a version of the citizen’s income promised by the Five Star Movement, a loosening of the previous government’s pension reform (as promised by both parties in the new coalition), as well as an increase in public investment.

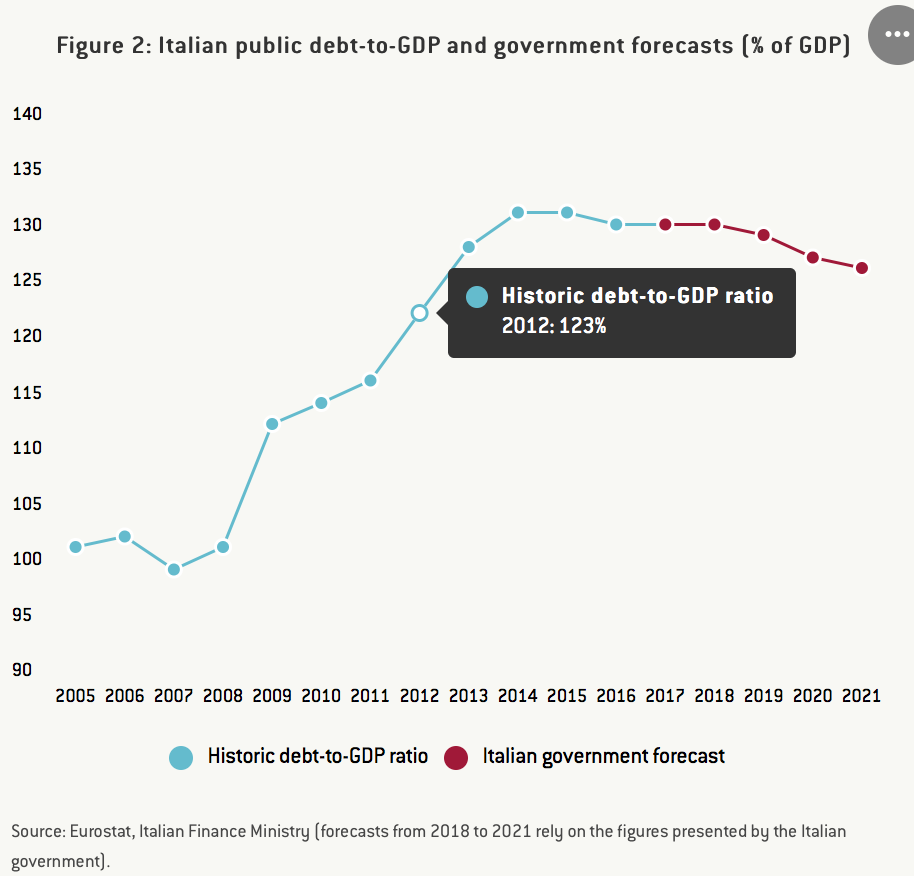

The headline deficit numbers announced for the moment are not dramatic per se (and should still be smaller than, for example, the French deficit figure), but the stock of public debt was already as high as 131.2% of GDP at the end of 2017. So, how will the new Italian fiscal plans affect the path of its debt-to-GDP ratio? According to the new documents published on October 4th, given the predictions of the government (i.e. a real growth rate of 1.5% for 2019, 1.6% for 2020 and 1.4% for the year after), Italy’s public debt as a share of GDP is supposed to fall over the forecast horizon to 124.6% in 2021 (see Figure 2).

However, these forecasts might be too optimistic. They appear at odds not only with the European Commission’s own forecasts (1.1% real growth for 2019), but with the perceived reduced growth prospects for 2019 at the global level and, more importantly, with the potential negative impact coming from the recent strong increase in Italian bond yields and the resulting tightening of financial conditions for the real economy.

Even if the increased deficit should have some short-term stimulating effect on an Italian economy that is still operating below potential, the government growth forecasts thus appear to be quite optimistic. If they do not materialise and if, as a result, deficits are higher than foreseen, it means that Italy’s public-debt-to-GDP will, at best, stagnate at a high level and, more probably, will be on the rise again in the next few years as a result of the new fiscal plans.

What Does the EU Fiscal Framework Say About the Current Italian Situation?

First, the Italian government, like other EU Member States, will have to formally submit to the Commission its budgetary plan for next year before mid-October. If the European Commission identifies serious non-compliance with Italy’s budgetary obligations, it will be able to react to this draft immediately and request a revision of the budgetary draft within three weeks (Art 7.2 of regulation 473/2013). After that, the Commission should also publish its formal opinion on the Italian plan for next year (and on those of other Member States) before the end of November.

If the Italian government does not revise its budget plans in response to the Commission’s recommendations, the Commission can mobilise the rules from the European fiscal framework to try to steer Italy’s fiscal policy towards a sustainable path. The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), the backbone of the EU fiscal framework, is composed of a preventive and a corrective arm (the latter is also known as the excessive deficit procedure). Both levers could be activated in the Italian case.

First Option: The European Commission Could Sanction Italy for Not Respecting the Preventive Arm of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP)

The preventive arm requires Member States’ structural balance to converge towards a country-specific medium-term budgetary objective (MTO), i.e. 0% in the case of Italy. Like other members, Italy should be at its MTO, or on a path to reach it, with an improvement of its structural balance. The size of this adjustment depends on the macro conditions and level of debt (see flexibility matrix p20). In the case of Italy, given the country’s high debt level, the structural balance adjustment most recently recommended by the Commission was 0.6% for 2019 (see p18).

The preventive arm also requires Member States to abide by the expenditure benchmark (see details on the various fiscal rules in Claeys et al., 2016). If one of these two conditions are breached, the European Commission can launch a Significant Deviation Procedure. It constitutes the first step before (or to avoid) the opening of an Excessive Deficit Procedure.

In our case, the published budget plan suggests that the Italian government will indeed breach the rules of the preventive arm of the SGP by deliberately drifting away from its MTO (the new plan forecasts a worsening of the structural balance by 0.8 percentage points in 2019, see Table III. 6 p49) and by exceeding its expenditure benchmark.

The European Commission could thus send a warning to Italy. If the Italian government does not react within one month of the date of the adoption of the warning, the Council should, at that point, issue a recommendation urging the country to take the necessary policy measures to fulfil its European commitments. At its limit, in the preventive arm, a Council recommendation which is not respected can lead to an interest-bearing deposit of 0.2% of GDP, unless the Council decides otherwise by a qualified majority (Article 4 of regulation 1173/2011).

However, one element could delay the procedure: the SGP code of conduct stipulates that “the identification of a significant deviation […] should be based on outcomes as opposed to plans”. As a result, the intervention of the European Commission (at least as far as the preventive arm is concerned) could be deferred until the deviations are actually observed next year when the budget is executed.

Second Option: Italy Could Also be Placed Under the Corrective Arm of the SPG

However, the Commission could also directly decide to open an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) for Italy, following article 126 of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union.

EU countries are required to keep their budget deficit below 3% and their public-debt-to-GDP ratio lower than 60% – or if the debt ratio is above 60%, it should diminish at a sufficient pace. The Six-Pack legislation of 2011 quantified what “sufficient pace” means: the debt ratio should decline by 1/20th of the gap between the actual debt-to-GDP ratio and the 60% threshold, on average over three years. Given that Italy’s debt ratio stands at 131% of GDP, the gap to the 60% threshold is 71 percentage points, so the average annual decline should in theory be 71% divided by 20 – i.e. 3.55% of GDP per year. Therefore, the debt ratio should fall below 120% in the next three years, a criterion that the new projection of the Italian government does not meet.

So, it is not the 2.4% deficit figure that would be put forward as an argument by the European Commission, but an insufficient decline of Italy’s 131% debt-to-GDP ratio. Even though this justification has, to the extent of our knowledge, never been used until now, it is legally possible to open an EDP when a Member State’s debt is larger than 60% of GDP and is not being reduced at a satisfactory pace – even if its deficit is below 3%.

The SGP allows exceptions from this 1/20th debt-reduction rule, when a country implements reforms improving the long-run sustainability of the budget. This clause has been used in recent years to avoid placing Italy under an EDP. However, this year the proposed deviation from the debt-reduction trajectory is very significant and Italy is actually planning to reverse some reforms put in place in recent years, like the pension reform, so it might be difficult for the Commission to use this exception clause this time. We also note that the debt-reduction rule should be met ex ante too – that is, its fulfilment should be reflected in forecasts.

In terms of procedure, the first step would be a report by the Commission on whether to open an EDP against Italy. Three months after the submission of the budget, on the basis of this recommendation, the Council would decide whether an excessive deficit exists and, if so, to open an EDP with recommendations, deadlines and targets. At this stage, Italy would have three to six months to comply with the given recommendations – i.e. to amend its budget – before the Commission assesses if Italy has taken ‘effective action’. At that point, if Italy does not meet the given targets, the Council could decide on the type (and size) of sanctions it wants to impose on the country and assign new targets. If the non-compliance persists, the process would repeat itself.

In terms of possible sanctions, once it would enter the corrective arm of the SGP, Italy could be required (in case of serious non-compliance or if it has already been required to post an interest-bearing deposit under the preventive arm) to make a non-interest-bearing deposit until the deficit has been corrected. The country could also be sanctioned with a fine worth up to 0.5% of GDP (with a fixed component of 0.2% of GDP and a variable component). The Council could also decide to suspend part or all of the commitments or payments linked to European Structural and Investment Funds in Italy (recital 24 of regulation 1303/2013).

Will the Commission Exercise Its Powers?

From a purely legal perspective, the EU fiscal framework provides two options for the European Commission to try to influence the Italian fiscal policy, in order to put it on a sustainable path (these options are summarised in the timeline in Figure 3). However, in the end political considerations might dominate the next few months: as the European elections are approaching, the European Commission and the Council will be put in a delicate position. If they decide to apply the rules of the fiscal framework forcefully, they risk being used as a scapegoat for Italians’ bleak situation and face a further populist backlash in the country. But if they decide against applying the fiscal rules to Italy, they might embolden its government and reduce the credibility of the fiscal rules further, which would support populist movements in northern Europe.

In addition, market reaction and the opinion of rating agencies in the next few weeks (as S&P and Moody’s are supposed to review their ratingsbefore the end of the month) might also ultimately matter more than the European institutions’ decisions. Given the importance of ratings in the collateral framework of the ECB, downgrades could be dangerous for Italy: a downgrade by two notches by three of the major rating agencies and by three notches by DBRS would make Italian bonds ineligible as collateral in the ECB monetary operations. Although the probability of such a strong downgrade might not be that high for the moment – as a comparison, Italy was only downgraded three times in the heat of the crisis, between 2011 and 2013, at a time when the deficit was much higher – such an outcome would be highly damaging for the Italian banking sector and as a result for the Italian economy.

00 timeline italy - Infogram

It’s all good numbers but we won’t give a monkey and will push ahead with the reforms.Also we’ll Stop being net contributors of the EU and will come out of the €.Such an action will be the end of the Euro currency that has caused so much grief to a lot of countries.Plus a Euro referendum to come out of the EU shambles will signal the exit of the third largest economy and one of the pillars of the Union.Suit yourselves.Cheerioo #Italexit??

Sure, and that I guess we will be able to sail happily through the economic and social storm that would result from Quitaly right? All that we need and lack to flourish is the power to create money, not better education, better institutions, better regulation, etc. We will be able to print our way through a monster depression no problem.

I’m not sure that an euro referendum would go the way you say: italian saver’s bank accounts and italian wages are denominated in euro after all.

Are you sure that many people in Italy would agree to the idea: “ok let’s inflation eat out half of my wealth, perhaps also my wage/pension, so we can get more economic growth”?

Currently people don’t realize this and therefore they easily blame the EU and “Germans”, however consider that if the Italian government goes out of the euro it’s still italians who are supposed to pay back debts in euros (as I doubt the government could redenominate previous bonds) whit their taxes in devalued liras.

I think it would be faster for the italian government to declare unilateral bankruptcy, however I think this wouldn’t fly as it would be obvious that it’s italian’s wealth that would disappear, however going out from the euro would be the same as a disguised bankruptcy if the italian government could redenominate all bonds in liras (and redenominate also all bank debts and deposits in liras), with the advantage of being gentler and slower; if the italian governmenty couldn’t redenominate bonds, debts and deposits in liras it would probably be worse.

Also remember that most of Italy’s debt is italian’s private wealth, so it’s impossible to cancel this debt without cancelling also Italian’s private wealth, which is the reason this will not happen.

Private wealth is not evenly distributed. Those without much outnumber those that have, especially in the south, explaining why those now in power arrived in that position. Positive feelings re the euro are in sharp decline and will fall much further if Italy is pushed here.

The euro is a failed experiment that created a bankers paradise but screwed many, just as globalism did to the us flyover country. Past time for the euro to disappear… or at the least, have a northern (German) and southern (Latin) one so that the latins can devalue from time to time, which will bring trade more nearly into balance.

Italy is a net exporter, so trade balance is not the problem.

I think that inflation would be good for Italy, but at the condition that it is wage driven inflation (together with devaluation).

I just don’t think this is what this government is planning.

The Euro + ECB means the destruction of democracy. They have already toppled one Italian government with their meddling, imposing their broken theories against the will of the people and all economic sense. The result is good for keeping zombie banks alive but actual citizens suffer — and things could be so much better! It makes no sense for a country like Italy to have the same currency and interest rates as Germany. No wonder Italian unemployment is 3 times higher.

If Italy wants to maintain its democracy it needs to begin the exit process. Better to start now and plan properly than continue to suffer with an economy that remains smaller than it was a decade ago. The ECB has condemned a generation of Italians to unnecessary unemployment and poverty. They have proven they will not change and they will continue meddling. They have condemned a generation to unemployment and poverty. How many more lives will they ruin? Democracy cannot survive these conditions.

Thank you, Yves.

“The idea that a country with slack resources, mired in a slow-motion depression, should be running a fiscal surplus is absurd.” This is spot on and was the consensus that emerged at a talk about Italy in mid-July. There were academics, diplomats / civil servants and bankers from some EU states, including Italy, France and Germany. The German and French contingents agreed with their Italian counterparts that failure to cut Italy some slack would put the EU / Eurozone project at risk, but felt that the politicians and other elites benefitting from the current set-up would not countenance such heresy. It was felt that there was room to cut Italy some slack and such slack was economically sustainable. An official from the Bank of Italy commented that Brexit asked the right questions, but came up with the wrong answers. A German academic agreed. Bruegel’s Nicolas Veron added that a better leader than Le Pen could have exploited France’s woes and really threaten the EU (elite’s) project. None had any faith that the EU, even shorn of the UK, would reform. The powers that be have no incentive to do so. It’s just a slow death. The Italians felt Brexitannia had better prospects than Italy. Some figures about Italy’s declining birth and emigration rates were cited. When I returned to work, I told Italian colleagues about the discussion. They agreed with what was said. That explained the big cheer from Italian colleagues, bigger than that from English colleagues, when South Korea knocked Germany out of Russia 2018.

I believe that we have reached a point when german intransigence can trigger EU breakup as easily as it is written. If germans (German conservative leaders to be precise, accompanied by Netherlands’ and whatever) believe that the EU is their pet club to appoint their rules to their own convenience, and with such intransigence, the project is doomed. No matter how europhile is the feeling rigth now. After IPCC recommendations on CO2 emissions, Germany (again, the “leaders”) is/are trying to water it down on fears about their automotive industry. A case can be made that Germany, preaching for supposedly financial probity in one side is, on the other side, evading responsibilities on environmental issues. In both cases Germany is just protecting their industries. A case of an Empire disguised as a Union. There are useful stupids working for Germany (sorry, the conservative leadership) like Macron and the ultra-stupid Ciudadanos-PP complex in Spain, but anyway the Union will break if this is the course. In that case the breakup will be a no-deal one.

Yeah right. The current situation is everybody’ s fault, except Italy’s of course.

I seem to have heard that after Word War 2 all western European countries started off at about the same footing… except Germany of course, who were facing significant disadvantages, like their whole industrial base being not more than a smouldering heap of rubble.

And now here you are, bloviating “…If germans (German conservative leaders to be precise, accompanied by Netherlands’ and whatever) believe that the EU is their pet club to appoint their rules to their own convenience, and with such intransigence, the project is doomed…”.

If you want to play the blame game, I as a Dutchman have as much right to blame the incredible series of incompetent governments and rampant corruption in Italy for the economic predicament Italy finds itself in. And to top it off, it will probably again be these despised Dutch and German taxpayers that are going to foot the bill for Italy’s economic and political follies.

Gimme a break.

Jos Oskam: Please

https://www.spectator.co.uk/2018/10/a-greek-tragedy-how-the-eu-is-destroying-a-country/

From today’s Links page. Let’s hope that you get a chance to apply the same economic policies in the Netherlands that you insist on elsewhere. The eternal problem with Calvinism is that Calvinists always are eager to seek the damnation of others, now isn’t it?

This is your blaming game? Very poor indeed. Blame it on italian pensioners who are just, according to your vision, guilty for the “rampant corruption” you denounce and must suffer declining pensions.

And what about the stupid argument that you are paying those corrupt governments with your taxes?

First, Italy is a net contributor to the EU.

Second, the EU budget, which is just 1% of EU GDP, has never been, and cannot be used in the EU to rescue any corrupt government.

“And to top it off, it will probably again be these despised Dutch and German taxpayers that are going to foot the bill for Italy’s economic and political follies” . I was accustomed to read brainwashed Germans repeating these kinds of commonplaces sadly spreaded by their MSM, and now I see Dutches are infected too. As much as for Germans,in the past I could have recommended you to turn your taxpayer anger towards your own private banking system, for instance, and to consider that in the last 25 years Italy has been more “fiscally responsible” than Germany ( than Netherlands, I don’t know ), running chronic budget primary advances, for instance. Anyway, your last sentence is a good evidence of the fact that you haven’t the faintest idea of what you are talking about.Incidentally,as for history, some years after WWII your ancestors/ taxpayers, along with many other countries ones,were happy( maybe or maybe not ) to bear a debt jubilee in West Germany’s favour, as USA had previously decided to trash the Morgenthau Plan and had decided that W.Germany development was crucial for the Western block.

Sorry, competent/incompetent governments cannot be blamed for the systemic problem: the euro. That condition is indifferent to the public policy of the EU member states, and because of the way it’s structured, has a deflationary bias.

Imagine as the U.S. encountered the Great Recession, its central government decided to withhold Social Security, Medicare and revenue sharing payments from Florida. Would it matter how well Florida was governed? Answer: No, that would make any downturn in Florida worst with the austerity it visited on Floridians. Yet that withholding is exactly what Greece encountered.

When the EU gets fiscal governance to match its monetary unity, then its conceivable some solution can arrive.

Meanwhile, condemning those bad, bad Italians is just more xenophobic bias, exactly like Trump uses on Puerto Rico. It blames the victim.

I’d thought better of the Naked Capitalism commentariat, frankly.

Perhaps one day a majority of voters in the EU will wake up and figure out that direct matching of money creation to resources can be undertaken by governments without fat cats having a slice of this action.

The idea that a country should allow its economy to be run by foreigners is what’s really absurd. Seriously, Greece was better off in the early 1940s under Nazi occupation than it is today. That’s because the first German occupation only lasted four years. Today you have the 4th Reich, renaming itself European, and occupying Greece for a decade, with no end in sight.

In the past people were willing to sacrifice their lives for their country’s freedom. Often such sacrifice occurred when their was little hope of succeeding. Compare that to the 21st century westerner. I do not think it is unfair to suggest that we have all been bribed to give up our freedom. Even NC, with its valuable insights, puts the economic well being of people above any other consideration. All this is fine and dandy so long as the central authority delivers prosperity. Once the system begins to fail people they will rebel. It is inevitable because we all understand that the global elites are only looking after themselves. The tools they use, such as the Viertel Reich and American Empire, benefit the average citizen little – plus we’ve reached the stage of diminishing returns.

So you will see a return to nationalism and its rise will be determined by people’s loss of prosperity. All the slandering in the world of the Le Pens and Farages by the Left Wing Freak Show will not prevent this.

Imagine if the US government dictated what each state was allowed put in its budget. What if Uncle Sam dictated tax increases and benefit cuts and directly controlled interest rates on state debt, so if any state got out of line they were quickly whipped into line. I think we’d have several states in open rebellion in a short amount of time.

I still find it hard to believe anyone with a left leaning conscious can continue to shill for the toxic EUR, specifically how it has been deployed in the Southern European economies.

There many good things about the EU, the EUR is not one of them.

And the whole problem around the Brexit conversation is one of polarisation. To the remainers, the EU can do no wrong, to Brexiters its all wrong. Truth is as usual somewhere in the middle.

This is a finance and economics site. Informing readers as to what the European Commission might do if Italy does not back down is not shilling for it.