Yves here. Perhaps this sort of thing will come sooner rather than later, but I wish Green New Deal were putting more emphasis on measures that can be implemented quickly to cut energy use, like conservation and energy efficiency, over things that take more lead times and can get into NIMBY problems, like building more wind turbines. We don’t have time to waste, and too much emphasis on visionary schemes risks that.

By David Cash, Dean, John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston. Originally published at The Conversation

The Green New Deal, a bundle of proposed policies that would combat climate change, create green jobs and address economic inequities, is eliciting the usual partisan debate over what to do about global warming.

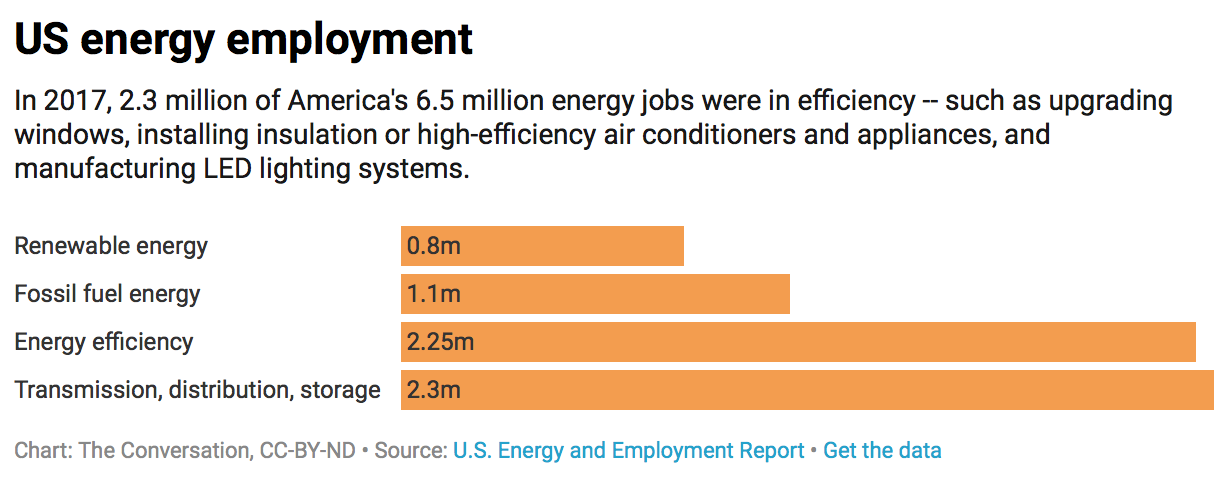

But one humble and noncontroversial way to reduce carbon pollution has been gathering steam in red and blue states alike: energy efficiency. Policies like those that encourage the retrofitting of low-income homes in Texas with insulation and provide cash incentives for new homes in Vermont that generate as much power as they consume are reducing carbon emissions and pollution while creating jobs. Some 2.25 million people are working in the swiftly growing sector.

Although it gets much less attention than other clean-energy industries, like wind and solar power and electric vehicles, efficiency is booming. The electricity these improvements save grew by 50 percent between 2013 and 2017. In 2017, the U.S. conserved the equivalent of all the energy Denmark produced.

As a scholar of energy and environmental policy, who spent a decade working for the Massachusetts state government, I believe that because of its environmental benefits and job growth potential, energy efficiency will be the bedrock of both national and state energy policy, regardless of which party controls statehouses, Congress or the White House.

Why? Because, the policies that support energy efficiency expansion are those that can be embraced by conservatives and progressives alike, whether they are cast as buttressing a “green new deal,” “energy independence” or “workforce development” strategies.

Counting Jobs

Energy efficiency helps keep your beer cold, workspaces well-lit and clothes clean for a fraction what it would cost to build a new power plants of any kind. It also tends to be uncontroversial because it does not require the construction of big new industrial infrastructure.

Although you might associate the concept with setting thermostats uncomfortably low or mindfully turning off lights in empty rooms, current energy efficiency improvements generally don’t force anyone to change their habits. While reducing pollution and sparking innovation and entrepreneurship, they save money for customers and businesses, and are especially beneficial for low-income households, whose energy costs take up a large portion of their budget.

Until recently, it has been hard to directly track energy efficiency job growth, though. The federal government and most states did not even try until 2017, when the Energy Department began to release national energy jobs report. In addition, E2 and E4TheFuture, two nonpartisan and nonprofit groups that advocate for policies that are good for the environment and the business world, create state-by-state assessments.

With 2.25 million workers, the sector now employs twice as many as all fossil fuel sectors combined, according to the federal energy jobs report. And energy efficiency accounted for half of all energy job growth in 2017, according to E2’s report on energy efficiency jobs.

Virtually all energy efficiency jobs are local by definition, although manufacturing of energy efficiency products can happen overseas. Thus, these jobs are generally immune to outsourcing since they have to be done on-site. Yet that is not necessarily true for all energy efficiency employers.

An estimated 350,000 businesses, ranging from local startups to large multinationals, conduct energy audits and make efficiency upgrades in homes and commercial and industrial buildings. They manufacture and install high efficiency systems, windows, LED lighting and insulation, upgrade and repair HVAC and water heating equipment, code operations software, and design and construct high-performance buildings.

State Leadership

While the Trump administration continues to dismantle policies that advance clean energy, many states are stepping up their efforts to reduce carbon emissions.

I consider Massachusetts a good example. It has made energy efficiency a high priority since 2008, when a law called the Green Communities Acttransformed rules and introduced energy efficiency incentives.

In the 10 years since its enactment, annual investments by utility companies in statewide energy efficiency programs rose from about $125 million to more than $700 million. That investment provided a nearly 4.5-to-1 return in terms of energy savings that created more than 84,000 new jobs.

The climate change benefits were significant too. By reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 1.8 million metric tons over the most recent three-year reporting period, the program achieved the equivalent of taking 390,000 cars off of Massachusetts roads.

Experts like the energy analyst Hal Harvey and the Tufts University scholar Gilbert Metcalf have documented these kinds of cost savings and emissions benefits for years, as have government authorities and utilities.

Nonpartisan Patterns

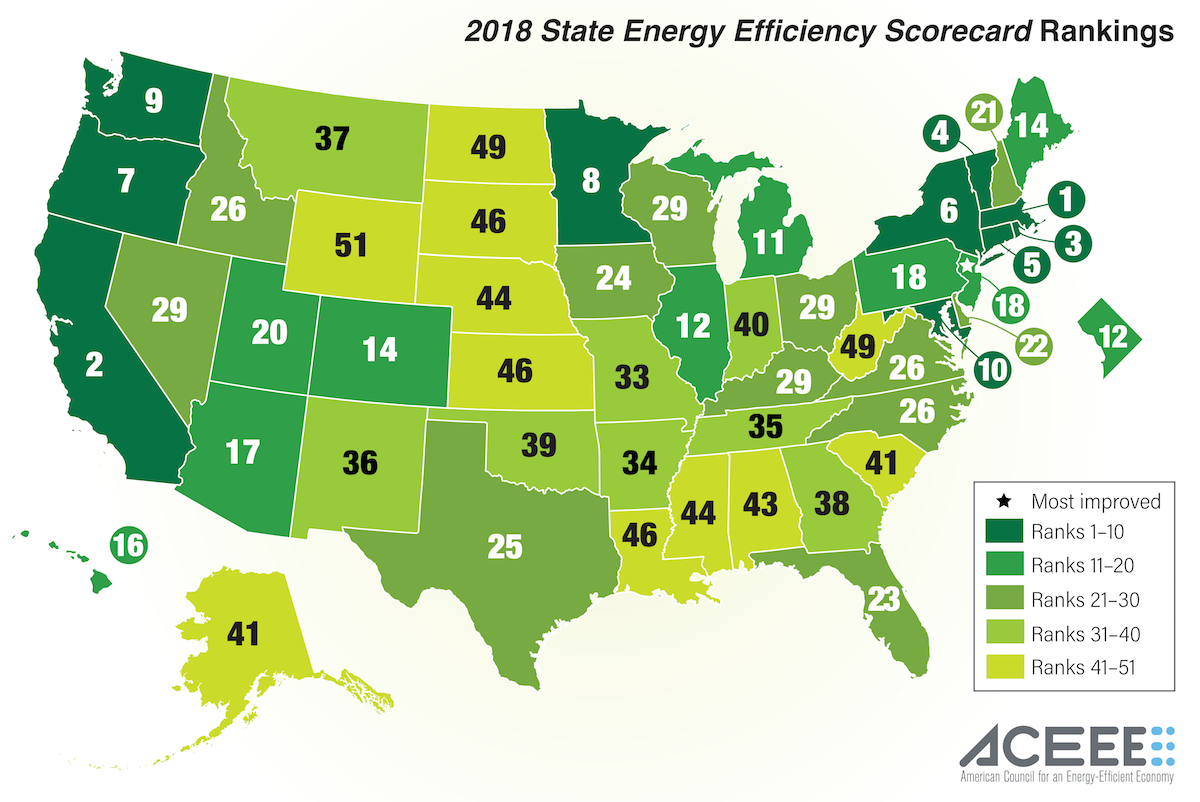

Energy efficiency is popular in states led by Republicans and Democrats alike.

Efforts by the Democratic strongholds known as “blue states” to encourage energy efficiency have paid off for states like California, New York and Oregon. All three are among the 10 best in terms of carbon dioxide emissions per capita, energy expenditures per capita and energy use per capita.

But even in Republican-led “red states,” such as Texas, South Carolina, Missouri and Utah, energy efficiency is beginning to take off. For example energy efficiency construction jobs make up between 10-24 percent of all construction jobs in those states.

While energy efficiency is on the rise across the nation, there are still critiques of the policies encouraging these efforts. Such arguments center around regulatory overreach, the upfront costs of such programs and the potential loss of revenue for utilities. Amid concerns about the quality of some technologies, such as compact fluorescent lightbulbs, the Trump administration is trying to roll back a mandate to make all lighting more energy-efficient.

But there are many examples of where energy efficiency policies have succeeded in tandem with technological innovations.

Near-term federal action on the Green New Deal’s stated rationale, “addressing the existential challenge of climate change,” currently appears highly unlikely given the lack of support from Senate Republicans and the White House.

However, like some observers, I suspect that Congress may consider less comprehensive energy legislation before long. Because there is much to gain on both sides of the aisle by lowering constituents’ utility bills and growing jobs in a sector that has demonstrated potential, energy efficiency could be at the center of new energy politics and policies.

Excellent post. Thank you!

One thing we need in the north country is thermal well technology. IMO entire cities will have to be refitted with new heating technology to take advantage of ground temperature. I envision entire neighborhoods sharing wells to defray infrastructure investment.

Actually, unless the site is connected to volcanic activity geothermal isn’t replaced nearly as fast as it is used…so not really, usually, renewable. But solar thermal has big potential.

I think domestic energy savings should be the absolute first priority for a GND. Its not just that it delivers quick and immediate emission drops – much quicker than most green energy projects – but it is a major job creator, especially among the unskilled to semi-skilled. Its ideal for implementing Job Guarantee schemes and can be focused first of all on low income homes. It also means people are immediately seeing results, rather than the abstract of CO2 emission figures.

There is enormous low hanging fruit here – the average US household uses three times the electricity of a German house – and German houses are more likely to have electricity water and space heating.

It also has other benefits for reducing carbon emissions in that reducing peak time domestic use can both improve the efficiency of electricity power networks and allow for a cheap form of storage (by installing smart meters and encouraging night time use for water heating).

It won’t come cheap however – there are something like 130 million households in the US. Some simple maths would show that it will cost in the trillions over a decade or so. About the cost of one or two foreign wars….

Have they done the calculations on whether the carbon footprint of the upgrades would outweigh the carbon reduction of the improvements? Because we need the carbon reductions now, not over time.

That’s an incredibly important point I haven’t seen anyone bring up before.

Great article. The equation on climate change figth is incomplete if we do not take a comprehensive look to all the energy process from production to consumption, find ways to reduce energy waste and improve efficiency (while not sacrificing minimal needed performance).

Regulatory overreach: there is now way to overreach on our need to figth climate change, or at least we are very very far from it. This is not a real concern, it is ideology put before an essential need.

Upfront costs: this is a problem given current state of inequality. So, reduce inequality.

Loss of revenue for utilities: sorry guys, you have to diversify. Start now!!!

Although energy efficiency is one of the needed legs in any meaningful GND scheme, for me the question is how do you force it and scale up as fast as needed. In the EU, the lead is taken by public institutions. Those are the first required to comply with more stringent limits on energy demand. Then there is the construction sector: new buildings have to comply also. The real challenge is how to transform the existing building & housing stock in order to make it comply with those limitations. Here is where the EU is going too slow. Energy consumption has in fact increased in the EU in 2016 and 2017 making goals projected into 2020 almost unachifevable. You can indulge in different explanations (weather, GDP growth…) but the real problem is energy efficiency in the existing stock of buildings. Improvements are proceeding too slowly and austerity does not help. Governments are constrained to offer incentives (very limited in countries that are under the excessive debt microscope) and initiative is let in the hands on those who are really compromised (a minority should I say, at least in Madrid, where I sense the real state of the opinion). Training the needed workforce is left to markets while adoption of more efficient technologies is pushed via regulatory frameworks (such as ErP directive).

To be sure we are witnessing a rapid rise in energy-efficiency services companies. In Spain this is apparent from december 2017 so I hope that by 2020 the impulse will have grown, nevertheless I believe that if public financial help is not scaled up by much the objectives for 2020 and 2030 will not be accomplished regardless you consider those timid or ambitious.

I agree that energy efficiency (and good ol conservation, too) must be priority issues. But why pick on the GND? IIRC, the goal of retrofitting all residential homes for greater efficiency is the closest it gets to a real policy proposal.

Plus, I welcome the GND improvements to current policy. For example, here in MA, which is a leader, I recently became a home owner. My wife and I have invested $20K in energy improvements, including solar and high-efficiency heat pumps, using great incentives. However, getting our antique farmhouse sealed for greater efficiency is near impossible using the incentives available – so much of the work necessary is not “part of the program”, leading to dealing with multiple contractors with conflicting goals, confusing costs, etc.

Yes. There are difficult cases. You have to consider various possibilities depending on the intended use.

Of course, the costs incurred in houses that are used temporally are usually too high for the benefit obtained unless you think of it as an investment that will payback when you sell it.

We are (relatively) young and intend to die in our home. It’s just the current debt load precludes making the next set of efficiency steps, which will eventually pay for themselves, but which we cannot well afford now without reasonable incentives.

I just replaced the 20 year old HVAC in my house. It will pay for itself in two years, that’s how bad the old stuff was. Looking at the efficiency just in the last few years some of the stuff has increased 10 fold.

I looked hard at PV’s but the capital cost was astronomical even with the tax credits. I really thought at the time the stuff had the incentives baked into the pricing, and I’m not at a great latitude for it. I’m still looking at it as an alternative to a generator to provide basic power for the well and refrigeration, and that makes some economic sense.

Hey, this is contradictory with a former comment from you in a different post on the impossibility to do anything meaningful against climate change. Let me tell you It makes me double-happy to read this comment. I see you are a compromised person! Bravo!

“Incentives baked into the pricing”.

I was highly suspicious of this myself. For those who don’t understand, the concept is simple.

The local contractor bids the new $15,000 Hvac system at $22,500 so the homeowner qualifies for the full $7,500 federal tax rebate (30%).

Essentially, the contractor steals your tax credit.

Once one does it, they all get on board, making it impossible to get an honest bid.

First of all, congratulations.

Second, I am totally uninformed on this subject, but wouldn’t it be possible to just insulate the house room by room starting with the rooms where you spend the most time? Or does it really require insulating the entire house, especially the attic?

And how does one get objective information on this subject when there are so many profit motives at work?

Also, you made me think of John Adams’s original home in Quincy (not his mansion). He wrote about how drafty it was. I think the early colonists enjoyed such abundant firewood they didn’t really think about drafts and it was already an issue by John’s day.

Each room has different warming/cooling loads requirements. You may try isolation outside, inside or within the wall if you have an air chamber. If your heating system allows for zoning it is great when the use you give to each zone is different. For instance, it is a good idea to put dumb thermostatic valves on each room if there are radiators.

I cannot help on where to find good advice but can recommend, for those interested a book titled “Sustainable Home Refurbishment” from David Thorpe

Depending on your utility, many have free energy audit programs that can suggest what and who to do the work.

I could go room by room. But what I would like is the whole house sealing provided “free” through utility efficiency programs in MA. But the name is misleading. I need to do significant renovations to attic joists to allow sealing work. Then the sealing does not include replacement of the solid wood, single pane, ill fitted doors I have. So, not free or reasonable for me, and many others in the area.

So many liberal programs seem to turn out disappointing when it’s time to spend the $. When I wanted to claim the Earned Income Tax credit in Mass. one year, the state asked me for a copy of my paper Social Security card (not driver’s license or passport which I have with me)! I had no idea where that was, and I didn’t make the time to fight it out with the state over a small amount of money, so the state saved itself that money it claims it’s using to help alleviate inequality. How do people who depend on the state’s assistance get by?

All excellent points.

Really effective energy conservation (beyond nibbling around the edges) in older homes is complicated and very often beyond what the average home owner is capable of in terms of time, expertise, or resources. The state needs to develop programs to make the process easier and more affordable. Many, for instance, can’t afford to make such an investment and then get it back in tax breaks. They need the resources and the expertise up front.

One option you might consider is getting an independent energy efficiency rater to do an evaluation of your home. If you are in New England you might consider getting a HERS rater (Home Energy Rating System), or some such equivalent (HERS may be considerably more widespread now) , to come and do the various tests (one of the main ones being a blower/door test) to determine where your particular house looses the most heat and what might be the most logical and cost saving sequences of steps (alternative plans) to get the greatest bang for your buck in making it comfortable and energy efficient. This works well for people who want to do it in steps or phases due to cost and time. Such a service will cost you anywhere from 500 to 1500 dollars for an average home depending on size and complexity. It is well worth it as getting someone who doesn’t do the actual work will ensure that you are avoiding conflicts of interest, and a good HERS rater will give you valuable advice on alternate plans to achieve your particular goals suited to your budget. While some raters are also contractors, they are required to avoid conflict of interests and usually do not do the renovation work themselves or if they do, provide you with a warning about conflicts. If you are doing just a single room, you might be able to get such advice more cheaply starting with just a phone call.

The following is a generalization and as all such, is subject to being misleading depending on the individual case and one should always check local code regulations to see if you need a permit. In New England, you can go to town hall, for instance.

In general (but particularly with older homes in colder climates), think of your house the way you think of a fireplace and chimney. Convection, the movement of heat loaded air, moves the air from basement to attic and the heat with it, or more accurately the heat is what creates the movement of air from basement to attic and on out of the house much the way it works in a traditional fireplace and chimney. Convection is one of the three ways heat is transmitted (along with radiation and conduction) and turns out to be one of the biggest culprits in heat loss of older houses.

You loose approximately 70% – 80% of your heat through your attic (or roof). So for pure bang for the buck, one always starts with the entire attic (usually between the the joists supporting the attic floor if there is an attic floor). Usually, you can’t do “part of your attic” and expect any noticeable overall result.

The next logical step in retrofitting thermal barriers in a house depends on your wallet, your time, etc., but one of the options people often overlook is the option of doing your basement – again between the joists in typical US construction. Because of the chimney effect (where heat from the attic escapes and creates a flow of air going from the basement (or crawl space) right up through every nook and cranny, every pipe hole, unsealed duct holes, etc., etc., the basement turns out to be a very significant source of heat loss due to convection. Because the basement it is usually more accessible than the walls, it presents a very good option number 2 after insulating the attic. Note that doing one’s basement should be done at the same time as filling in any and all gaps on each floor going up to the attic from the basement.

Insulating (and airflow sealing) the outside walls of a house will give more bang than doing the basement, but at a considerably greater cost in money and time and in most cases frustration because of the need for ripping things apart and then putting them or something new back in its place. So in terms of bang for your buck, doing the cellar first may be the right way to go. But one good thing about exterior walls is that you can do one at a time. So on a tight budget, you might figure out where the prevalent wind comes from and tackle that side of the house first.

Finally, windows. Many consider doing windows first, but while that may make a room feel less drafty, windows are almost never a good place to start in terms of energy efficiency (or an effective thermal barrier) or bang for the buck. Moreover, you should resist salesmen’s attempts to get you to go triple pane until you have carefully done your own calculations regarding the cost difference (between say, double pane) as well as the difference in the U factor. It may well not justify the cost difference and also consider cost of repair in the event of the ubiquitous baseball or other accident. After a minimum upgrade to double pane, the big thing about windows is proper installation, meaning carefull and thorough layers of sealing of all components starting with the raw opening, to prevent air flow.

Can you do just one room? Yes, but usually not very efficiently unless the outer walls have already been done. This is not a particularly good way of doing a whole house, however. Products change, contractors are different, tying one effort (project) in with another is not always successful.

What are good insulation products? Again an independent energy rater (who won’t be doing the work), or a good insulation contractor, will provide the best advice for a specific goal. But one of the best general types of insulation for renovation projects where cost is a factor is blown in cellulose (the treated paper kind – NOT the fiberglass kind). This can NOT be used in homes that have knob and tube (or exposed) wiring that is still active as moisture getting into it can cause shorts and fires. One of the reasons it is so good is, given the proper depth, it provides not only an excellent thermal barrier in attics but prevents or significantly reduces the flow of air and thus loss of heat due to convection. It is also useful for exterior walls that do not already have some form of insulation in them (contractors can sometimes get this out with powerful vacuums) in so far as it can be blown in with only small holes being made in the walls (from outside or inside) which can be subsequently patched up with less repair than ripping off the various layers of wall down to the studs.

Closed and open cell foam (family of polyurethanes usually) is the best (and most expensive) form of insulation for sheer R value combined with with ability to seal walls/attics/basements and all manner of holes and openings air-tight. This approach almost always requires a professional for installation. Some exceptional results can be obtained by the initial use of foam (say one or two inches) to provide an airtight seal and a high initial R value, followed by some from of traditional insulation such as bat insulation (fiberglass rolls) or cellulose. And finally, the persistent homeowner can do-it-themselves with ridged foam, from a home-center such as a lumber yard or Home-Depot, cut slightly smaller than the stud or joist openings and “sealed in” by use of shims followed by spraying cans of foam around all edges to get an air tight seal. It takes time,but one can get results closely approximating the most expensive closed cell applications.

Warning. For those who have little or no experience with such projects, professional advice is almost a must. You can go to a huge amount of cost and effort only to find you have made ice-damn or some other issue worse than it was before. Speak to a friend who has experience, or hire an energy efficiency rater, or get an appropriate contractor over and offer to pay for advice.

An excellent resource on the general principals of building energy conservation is, Residential Energy – (Cost Savings and Comfort for Existing Buildings) – by John Drigger and Chris Dorsi

It’s a bit of a slog and somewhat technical, but is very comprehensive and I suspect rather suitable for the typical NC reader.

ice-damn-> ice-dam (although ice-damn is more expressive).Late reply, but thank you for the very thorough comment

I’m just trying to imagine what it would take to insulate a McMansion. I’m not sure that you really could successfully insulate one with all those windows and hodge-podge design issues. Considering the fact that they have somewhat of a reputation with the poor quality of their construction methods, I would hate to be in one in extreme heat or extreme cold with the power out.

You’re spot on that they present a problem, but it’s possible to make up for a multitude of sins with both open and closed cell foam in the right places (and it’s amazing where you can get the stuff to go.). What sometimes happens (which I think is exactly what you are touching upon) is that the house will meet the tolerances of the projected rating upon completion but as it “settles” will rapidly fall off from it over the next four to five years, or frequently issues such as mold will occur in the walls or similar problems (ice dam) sometimes caused by the combination of poor construction combined with complex “showy” architecture along with poorly thought out or poorly applied insulation actually exacerbating the problem.. All the crazy knee walls, and bump outs, and dormers, and so on, can add significantly to the problems.

As an aside, It’s interesting that some of the new building codes can only be met (as far as I know) by closed cell foam given traditional techniques. So, for instance, the R rating for an attic in zone 5 is now a whopping 48R which is impossible to achieve between 8 inch joists unless you used closed cell foam. You can’t do it with bat or with cellulose given the eight inch constraint. Could it be influence on the MA building department code division by the mfgs/installers of foam products???

That said, because of exactly the points you make, the shoddy McMansions will on occasion have problems being brought up to their “potential rating” as derived from the building plans. Hers raters, for instance, are frequently hired by insurance companies or lending banks to generate a potential rating based on the architectural plans to be followed up by an actual rating once the residence or building is built. Banks and Insurance companies will make the loans somewhat larger (extend more credit) and the insurance somewhat cheaper based on those projected figures, but only if the subsequent actual rating comes very close to or exceeds the potential one.

Actually that’s R-value, not R rating and by code on new houses, it is 49, not 48, not that it makes much difference to my point.

One of the issues I have with the GND is that much of the focus appears aimed at encouraging wind and solar electricity rather than an outright reduction in GHG emissions. Earlier in the week, I mentioned here that the only explicit target in the legislation was 100% clean, renewable energy. It seemed more aimed at checking boxes for the Democratic base on the coasts than delivering meaningful reductions in pollution.

Given the outright hostility to it by the GOP and the long time frame of the infrastructure construction called for in it, how long will it be before we see the major project construction start? It might very well take 10 years. We need action today and grandstanding on the issue will only make it harder to implement any improvements over the Trump presidency.

I think this is one area (of many) where Democrats needed to be smarter and draft smaller-scale legislation that Trump would support. Perhaps his experience in real estate would make him open to energy efficiency in commercial office buildings (especially smaller ones), which are often underserved by government programs or policies to encourage domestic manufacturing of wind turbines, solar panels and large batteries.

Trump wouldn’t support any of it. The Senate Republicans ( plus the Senate coal state Democrats) would vote against it.

That’s okay. Make them vote against it in public. Make them reveal themselves over and over and over again. And make Trump reveal himself by vetoing any such legislation if it reached him ( which a coalition of Republican and coal state Democratic Senators would make sure it never does).

Make the Enemy reveal itself in public.

If you look at EIA projections of electricity use going forward, the trend is flat even though the number of customers increases 2-3% per year. Average use is declining.

There are two components of that decrease: 1) energy efficiency programs to replace/upgrade systems, insulation, windows, etc. and 2) codes and standards upgrades requiring new items to be more energy efficient.

It is the latter that our low intellect (it’s not pc to say moron) President is trying to stop. For instance if you look at refrigerators, they have doubled in efficiency over the last 10 to 15 years. If your fridge is old, buying a new one will save up to half the energy. The easiest way to save energy is to replace all your light bulbs with led’s at about a buck each. We replaced all of ours five years ago (saved 150 kWh/month) at $10 each and their cost has been paid back last year at PG&E’s exorbitant rates. Replacing things like printers with sleep mode printers, cable and satellite boxes, water and energy efficient dishwashers, installing a heat pump water heater (not cheap), etc are things an individual can do. Pushing cities/utilities to install LEDs in streetlights is a quick payback energy saving solution.

+1 on LED’s. We stumbled across this. We have a chandelier that provides the majority of our main floor lighting and I noticed the switch was literally hot to the touch. At first I thought it was the dimmer but I calculated the draw from it and was shocked. The things you don’t think about when you buy a house……

What kind of bulbs is that chandelier using?

When my father in law moved in three and a half years ago I bought him two LED lamps. That’s what you can buy these days if you don’t want to hunt around. The bulbs are built in, which didn’t thrill me, but the boxes claimed that the bulbs would use almost no energy and would last forever and ever. Well, all two lamps have totally disintegrated and are useless, one in a way that is actually dangerous (if you press the clamp you can badly gouge your finger; given my FIL’s thin skin that is extra bad). So now we have to throw out two big pieces of electrical-appliance plastic. Yes, the bulbs are still good, so what; no amount of rigging on my part works to to keep them upright or safe. I would rather have kept using old, sturdy lamps. Now I’m stuck buying more of the same junk, unless I want to scour Goodwill for something used.

Why didn’t you buy a screw in LED lightbulb for the “old sturdy lamps”? That’s what I did.

I’ve done a lot of that. That has taken care of my own needs. I needed to get more lighting for my father in law, who had just moved in. I could have scrounged some old lamps at Goodwill for him (and added LED bulbs), but I assumed that the new LED lamps would not be total junk. I think they have been a net debit for the planet.

This is an energy efficient community whose design has proven effective for decades:

https://www.context.org/iclib/ic35/browning/

A) California set to take big steps along energy efficiency:

https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/california-regulators-get-serious-about-building-decarbonization#gs.WJzn4nm6

The new proceeding has four goals: implement SB 1477, a bill signed by Gov. Brown last September that requires the CPUC to oversee two new low-carbon heating programs; investigate potential pilot programs to build all-electric, zero-carbon buildings in areas damaged by wildfires; coordinate with the California Energy Commission on updates to the state’s building (Title 24) and appliance (Title 20) energy efficiency standards; and establish a building decarbonization policy framework.

B) Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) has already taken big steps in this direction. An electric home must not have gas service to the premise.

https://www.smud.org/en/Going-Green/Smart-Homes

C) In 2020 all new homes under 3 stories must have solar that provides net energy usage for the building.

https://www.smud.org/-/media/Documents/Going-Green/AE-Diagram-BH.ashx?la=en&hash=A4FE821BAE02899976A579657AACB5F8FBF5D95B

Given the importance of this subject and this task ( energy efficiency upgrading and energy use down-shifting), commenters would probably want to submit hopefully-useful advice on particular ways to do that, and I see that some of us have.

If enough commenters were to submit enough useable actionable advice, other readers might want to come here to find that kind of advice, if they suspected they would find enough of it in one place and at one time to be an efficient use of their time.

One wonders if creating a very clearly and obviously named category for posts about energy and material use efficiency where all such posts and their threads were grouped together under one single easy-to-find topic-name . . . . would eventually attract even more readers looking for an ever-growing body of information and/or links to information about energy efficiency? Perhaps the Topic Title could have a totally clear name like Saving Energy? Or Saving Energy and Resources? Or Matter and Energy Efficiency? or some such thing?

Improving energy efficiency is fine, but the lowest of the low hanging fruit is to simply use less, and I don’t see anything in the GND or anywhere else talking about this. We insulated and weatherstripped the heck out of our small house, but then we attacked energy use head on: curtained off the space we spend the most time in to concentrate heating there; set thermostat at 57 day / 50 night; and invested in thermal layers (we’re in MI). In summer we’ll switch from a south-facing to a north-facing space, and use a fan to keep cool. Also use daylighting (no lights during day) and two low-wattage LED bulbs at night. Ditched the dryer, use a manual carpet sweeper and broom, wash dishes by hand in very little water. Cook with a solar oven (when sunny) or use induction burner and Wonderbag (aka fireless cooker). Oh – and another biggie: keep the hot water heater turned off, and only turn it on 45 minutes before a shower. Basically the only things still drawing power or burning fossil fuels are the furnace fan, clothes washing machine (1x/week), efficient refrigerator, and laptops. What this means is that if we install solar panels to over our electricity use, the system needed will be very very small (energy from solar panels and wind is not really “free”; each system has embodied energy which can be annualized as emissions over their lifetime). Here is an interesting article on energy efficiency: https://www.resilience.org/stories/2018-12-13/keeping-some-of-the-lights-on-redefining-energy-security/

I once posted the notion that, “those who can, should” (make efforts to conserve on energy from individual to public policy) and was called out for it along the lines that, “Everyone should do it.”

But the sad reality is that not everyone CAN do it and that applies to your, otherwise reasonable advice.. I can show you large sections of Worcester or Springfield, Massachusetts (just off the top of my head, i.e. not restricted to) where even homeowners simply do not have the financial resources to even worry about energy conservation, never mind fork over the considerable sums needed to do it effectively on older homes. They are flat out doing everything they can just to afford putting food on the table , never mind all the forms of rent extraction they are subject to such as greater than average stops by police where they must pay a ticket of one sort or another just to give one nasty example or needed drugs for medical reasons to give another nasty example, or real estate taxes, or water bills, and on and on and on. For them, energy conservation is right up there with a trip to outer space on RocketX, or whatever it’s called and their houses are already too cold for comfort and often for optimal health given frequent medical issues.

Renters are even worse off in such areas. They do indeed put up plastic sheets followed by shrinking with hair dryers to cover windows (meaning they get less fresh air) and other such strategies, but those only go so far.

That said, I agree with you in a somewhat limited sense. I’ve found that even at my age, I can get used to lower temperatures over the course of the winter by simply lowering the heat a little at a time. But I don’t think this strategy overall is a robust answer to the problem of energy conservation.

A point I didn’t make sufficiently clear is that these people’s lives are so tied up with making ends meet, that they simply can not focus (or make their family focus) on the energy conservation life-style you describe. They just don’t have the energy or motive left over at the end of each day (never mind month).

What they really need is a government agency that comes in (upon request) and does the work to make their homes energy efficient at no cost, period, and as little disruption as possible. Or better pay for their jobs as AOC suggests in her GND. Not some tax rebate scheme that they have to wait for – they have zero money to afford such a wait.

My state had such a program. Made people extremely ill due to sick building symdrome. There’s such a thing as making a house too tight.

Absolutely, but a well planned program will avoid that. The issue is now quite well understood and can be avoided either by 1) bld. codes (openings in attic and other key areas) materials and application techniques that allow appropriate “breathing” given bld. size, configuration, etc., or 2) the above plus air handlers combined with heat exchangers that bring in fresh air from outside and then exchange the heat from the stale air with the cold from the fresh air before letting the stale air (now cold) out of the house.. This requires some power to move the air and exchange the heat.

Yes, if course. In the longer version (blog form) I address those issues and preface by saying it applies to only the top half to two thirds of the income distribution in this country. Insulation can be expensive, but weatherstripping, less so. And most homeowners are able to turn down their thermostat, spend most time in a smaller part of their house, and turn off their water heater. I have low/no-income neighbors who use less energy than I do, and have done so for many decades. 90% or more of the materials they use are salvaged; not unlike where we’re likely to end up in the not too distant future.

I hear you and am largely in agreement. That said…,

Energy conservation is simply not in the vocabulary of many of the people I’m talking about except in so far as they are constrained to freeze (or boil) because they can’t afford otherwise. They have other issues too pressing to even take note of conservation except in so far as it affects their living conditions or their resources too much to ignore. And I find lowering the heat to painful levels because you can’t afford otherwise to be a nasty and often harmful motivation. Even then, their efforts, wrapping windows and sealing doors and using tape and lowering heat, etc., (even collectively) amount to nibbling around the edges of the problem.

They need hands on assistance on every level starting, no doubt with better job security and better pay, but we are talking about energy conservation here and because of the complexity and disruption that serious energy conservation efforts require in older (and particularly run down) buildings, never mind the disruption of daily life that it can entail, they need active comprehensive assistance in planning and execution and finance from start to finish.

This is assuming we are trying to use energy conservation as a tool to expand the time available to make the transition to renewable sources of energy and not simply to save on our energy bills. In this case we can’t leave those who can’t afford it out of the picture because they make up too much of the housing stock.

And this would go to rentals as well, though the forms of assistance, particularly financial, might reasonably be assessed differently. The main over-riding objective, however, is to get it done as quickly and thoroughly as possible; probably nothing short of an all out war-intensity effort..

A question arises about some of these measures and savings: what amount of purchased energy is used to keep any one particular house at 55 in the winter ( and in the same vein 85 in the summer)? And could the house be retro super-insulated and super-efficientised enough to where it could be kept at 65 in the winter and 75 in the summer for the same amount of purchased energy as would keep the house at 55/ 85 before the super-upgrades?

The question arises because not many people will adopt the level of personal non-use involved in keeping their house at 55/ 85. Whereas more people would accept super-upgrading their house to be able to live at 65/ 75 on the same energy at which you are currently keeping your house at 55/85. Those people would consider 55/85 to be “virtue hair-shirting” which they would not practice themselves.

( Though if an increasingly savage Hansen fee-and-rebate were charged against all fossil carbon fuel entering the market at the Instance Of First Sale . . . such that the fee got folded into the price and followed the price at every point of sale thereafter . . . those people could be price-tortured into 55/85 just to survive economically).

I work for Sweet Grass County High school in Big Timber Montana and over the past 19 years have led energy efficiency projects at our school. I have baseline consumption data for all 19 years and currently we are down on our electrical consumption by 47%. Our projects focus on high return on investment items. Every facility in the nation can do the same.. our building is now more comfortable with better performance, saves $30,000 annually which is now being reinvested into our students. Our equipment lasts longer with less maintenance and as a side benefit it reduces our carbon footprint.

A happy combination of the “doing without” which Kris describes and the rising efficiency at a set-comfort-level which Sam Spector describes could achieve significant fossil-fuel-use reductions.

Here is my little gesture in the direction of doing-with-less/ doing without. I have a natural gas hot water heater. I have discovered that just the pilot light by itself keeps the water warm enough to shower with. To shave, I heat just enough water on the gas stove in a teakettle to make a sinkfull of water hot enough to soak-face with. If I got motivated enough to go farther, I would figure out how to build a small solar hot-water-heater able to batch-heat a sinkfull of shaving water without having to use any teakettle at all.

I read once in a Rodale book about saving energy and money . . . that the higher you set your fridge ( the more nearly-warm and just barely-even-on), the less electricity you would use running your fridge. So I tried that . . . setting my fridge as “warm” as I thought my food could stand. What I discovered with MY fridge is that at that level of just-barely-on-ness, it cut on and off, on and off very fast . . . going through way many duty-cycles per unit time. And with each cut-on of the fridge, the big horizontal wheel in my old analog electric meter jumped instantly forward by 5 of the tiniest little line-marks on the outer margin of the wheel. A power-surge for every cut-on of the fridge.

Whereas when I began re-colding the fridge, the number of duty-cycles went down. Each “off-half” of the cycle became much longer whereas each “on-half” of the cycle became no longer than before. I spent night after night timing the on and off halves of the duty cycle to see just what fridge setting gave me the lonnngggest complete on-off duty cycles. My own fridge’s Efficiency Sweet Spot was/ is at “zero”, midway between “warmest” and “coldest”. So in my fridge’s case, the gesture of using the least-possible by setting it at “warmest” actually degraded its performance and cost me MORE electricity. It took observation and experiment for me to find my fridge’s best-efficiency sweet spot.

Does every fridge have a highest-efficiency sweet spot? I don’t know. Maybe my fridge is the only fridge in America to have such an efficiency sweet spot. But what if all Two Hundred Million Fridges in America each had their very own sweet spot? What if Two Hundred Million individual fridge owners each found their very own fridge’s very own sweet spot? How much power would America’s Fridge Fleet be saving over all collectively?

The very strong possibility that grass-fed livestock helps agrisystems suck net-carbon down out of the air and sequester it down into the soil . . . . keeps oozing out from under the Cone of MSM Silence still being placed over that probable fact.

Here is an article about that placed where a fair number of people can see it, if they want to. It is called “Adding Balance To The Meat Debate” and showed up on Resilience.org.

https://www.resilience.org/stories/2019-02-15/adding-balance-to-the-meat-debate/