Yves here. Obviously, the observations about the pro-carbon-emissions bias in monetary policy applies to the US too. Will someone page AOC?

By Dirk Schoenmaker, Professor of Banking and Finance at the Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam. Originally published at VoxEU

Central banks traditionally take a long-term perspective on economic and financial developments. Through monetary policy they play an important role in the economy, and their mandate to ensure financial stability means they have an important role in the financial system too.

As part of this commitment, central banks have begun to examine the impact of climate-related risks on the stability of the financial system (Carney 2015). In monetary interventions, central banks have a long-standing policy of market neutrality, but there is evidence that the market has a bias towards carbon-intensive companies, and so monetary policy cannot be climate neutral (Matikainen et al. 2017). Doing nothing to meet this challenge is a decision that undermines the general policy of the EU to achieve a low-carbon economy.

In a recent paper (Schoenmaker 2019), I propose steering the allocation of the Eurosystem’s assets and collateral towards low-carbon sectors, which would reduce the cost of capital for these sectors relative to high-carbon sectors. A modest tilting approach could reduce carbon emissions in their portfolio by 44% and lower the cost of capital of low-carbon companies by four basis points. This can be done without interfering with the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Price stability, the primary objective, should remain the priority of the Eurosystem.

Carbon-Intensive Assets

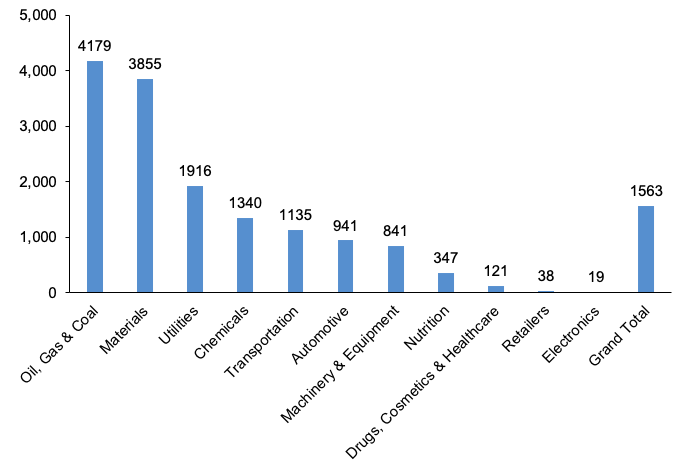

Carbon-intensive companies – such as fossil-fuel companies, utilities, car manufacturers and airlines – are typically capital-intensive. Market indices for equities and corporate bonds are therefore overweight in high-carbon assets. Figure 1 summarises the average carbon intensity, defined as carbon emissions divided by sales, of industrial sectors in Europe.

As we might expect, the oil, gas, and coal sector has the highest carbon intensity followed by the materials sector (metal producers and construction), utilities, chemicals, transportation (airlines), and automotive (carmakers). The lopsided distribution of carbon intensity shows that carbon emissions are concentrated in a few sectors.

Figure 1 Average carbon intensity by industry (emissions in tonnes of CO2 divided by sales in millions of euros)

Note: Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions are included for the 60 largest corporations in the euro area.

Source: Schoenmaker (2019).

In its monetary policy, the ECB – like any other central bank – follows a market-neutral approach in order to avoid market distortions. This means that it buys a proportion of the available corporate bonds in the market. This market-neutral approach leads to the Eurosystem’s private-sector asset and collateral base being relatively carbon-intensive too (Matikainen et al. 2017).

Investment in high-carbon companies reinforces the long-term lock-in of carbon in production processes and infrastructure. We can conclude that the ECB’s market-neutral approach undermines the broader policy of the EU to achieve a low-carbon economy.

Now that central banks have started to examine the impact of climate-related risks on the stability of the financial system (Carney 2015). Why not address the carbon intensity of assets and collateral in central banks’ monetary policy operations as well?

Legal Mandate

First, the legal mandate of central banks must allow the ‘greening’ of monetary policy. The primary responsibility of central banks is to maintain price stability, with a secondary responsibility to support economic growth. Interestingly, the EU applies a broad definition of economic growth. Article 3(3) of the Treaty on European Union says that:

“The Union shall establish an internal market. It shall work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability … and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment.”

This broad definition of sustainable economic growth could provide a legal basis for greening monetary policy.

The ECB can only pursue its secondary objectives as long as they do not conflict with its first objective. The proposed tilting approach would not lead to undue interference with price stability. As everyone is a stakeholder in the environment and the climate (Schoenmaker and Schramade 2019), the ECB could contribute to the climate agenda without getting into political discussions.

There is thus a need for political space for the ECB to avoid central bankers making policy decisions. As climate policy is a top priority of European policy on a consistent basis, the ECB can contribute to this secondary objective using its asset and collateral framework of monetary policy operations. The European Commission and Council have repeatedly stated their aim to combat climate change by reducing carbon emissions. European Parliament members have also asked questions to the ECB president about the ECB’s lack of carbon policies (see, for example, Draghi 2018).

Greening Monetary Policy Operations

I propose a tilting approach to steer the Eurosystem’s assets and collateral towards low-carbon companies (Schoenmaker 2019). The Eurosystem manages about €2.6 trillion of assets in its Asset Purchase Programme, which includes corporate and bank bonds in addition to government bonds.1 In its monetary policy operations, the Eurosystem provides funds to banks in exchange for collateral, which currently amounts to €1.6 trillion. A haircut is applied to the value of collateral, reflecting the credit risk.

To avoid disruptions to the transmission of its monetary policy to the economy, the Eurosystem should remain active in the entire market. The basic idea of tilting is to buy relatively more low-carbon assets (for example, a 50% overallocation) and fewer high-carbon assets (in this case, it would be a 50% underallocation). The Eurosystem can then apply a higher haircut to high-carbon assets. Calculations show that such a tilting approach could reduce carbon emissions in the Eurosystem’s corporate and bank bond portfolio by 44%.

Applying a higher haircut to high-carbon assets also makes them less attractive, reducing their liquidity. Early estimates indicate that this haircut could result in a higher cost of capital for high-carbon companies relative to low-carbon companies of four basis points.

Accelerating the Transition

A low-carbon allocation policy would reduce the financing cost of low-carbon companies, fostering low-carbon production. The higher cost of capital incentivises high-carbon companies to reform their production process using low-carbon technologies, because this will save on financing costs.

A low-carbon allocation policy in the Eurosystem’s asset and collateral framework would therefore contribute to the EU’s policy of accelerating the transition to a low-carbon economy. To avoid political interference, it is important that the Eurosystem remains fully independent in the choice and design of its allocation policies.

This allocation policy can and must be designed so it does not affect the effective implementation of monetary policy. Price stability is, and should remain, the top priority of the Eurosystem.

See original post for references

I would put a caveat on Figure 1. While ‘Electronics’ looks low on carbon, it is also a big user of ‘Materials’. Likewise, ‘Retailers’ use ‘Transportation’, and about everyone uses ‘Oil, Coal & Gas’. And I don’t see any ‘Agriculture’ (unless ‘Nutrition’ covers that).

While I don’t contest the ‘greening’ proposal, one might sit down a minute to correctly identify the ‘low-carbon’ assets – and perhaps find out that the real low-carbon assets are not-purchasable.

It’s almost like this late industrial era is trying to avoid the fact that time moves much slower than finance. “Low carbon assets are not purchasable” is an inconvenient truth. We managed to get our civilization so wound up in aggressive growth and vested interests that politicians are hog-tied. To let the earth (say big agra farmland or coral reefs, etc.) recover takes time, not “collateral.” And to do an estimate on what it will take to maintain price stability is virtually self defeating. I almost laughed when he said “4 basis points” would be enough capital inducement to encourage fossil fuel industries to switch over to green. Before that can work green will need to be heavily subsidized to get it up and running, so it is absurd to say the ECB has to isolate itself from playing favorites. This is all politics. It’s the nexus of our epiphany. But this is a start. I like the idea of the greening of the banksters.

Is this bias towards high-carbon investments in central banks also found in sovereign wealth funds like Norway’s? They may not have the same mandates to avoid market distortions and preserve price stability, but their portfolio is both large and very diverse in terms of the industries they are invested in, including large investments in the fossil fuel sector.

Obviously the fund itself is a product of oil revenue, but their recent moves to get out of some fossil fuel investments suggests they are also considering the long-term climate impact of the investments they make now. If they wanted to really green up their holdings would they have to take similar haircuts as the central banks in this proposal? Or is this an apples to oranges comparison?

Norway calls for $1 trillion fund to sell some oil and gas stocks

Thanks for the link, Ignacio.

I read another article from Phys.org when this was announced that maybe clarifies what I was getting at. Here’s an excerpt:

Obviously it’s positive that they are shifting their investments away from these sectors, but I just wondered if it would be impossible for the fund to remain financially viable if it was to take these measures in a more extreme direction.

Does this concept offer a exiting strategy for US Pension Funds to shift out of Fossil Fuel holdings in their portfolios–a conundrum; imo, of getting US toward a GND?

Doesn’t this amount to an MMT-based green policy driven directly through the central bank, rather than fiscal policies?

If so, it probably can be effective as a mechanism of changing costs — but, there is a contradiction in it, or a giant institutional problem captured in the last two sentences (to which it seems the author is completely oblivious or just takes monetary policy for granted as the hammer to drive every nail):

” To avoid political interference, it is important that the Eurosystem remains fully independent in the choice and design of its allocation policies.

This allocation policy can and must be designed so it does not affect the effective implementation of monetary policy. Price stability is, and should remain, the top priority of the Eurosystem.”

Huh? The central bank will remain independent, not political, but will pursue a green policy – which is what, not political? And also the central bank will have to make sure its overall monetary policy is not disturbed… Hmm… What mandate then will drive the central bank, what policy will guide it? Legislated by whom?

Accountable to whom?

Is this author saying that the central banks could just decide to do this just because then can? What ensures continuity and a well thought out relationship with other industrial and social policies?? Just the whim of the bankers to save the world???

So, I think as a tool this probably can slant the game to favor some greening of industries – but to assign this giant, profound task to a monetary policy knob and then just sit back and relax strikes me at best as economic ivory tower lunacy and at worst – as trying to avoid changing anything and ruffling no feathers. While the world is hurtling toward the precipice.

PS. The legal basis for this, that the author mentions, may sound plausible and sufficient in the context of the EU, to Europeans who are trained to accept everything coming from the desks of EU bureaucrats as binding order, if not law (which is hugely problematic for the EU, and as Varoufakis pointed out, leaves huge gaps of accountability). But how would that work in the US? How will we keep an independent gigantically powerful institution accountable and doing sensible things with just one vague sentence like this?

“”Article 3(3) of the Treaty on European Union says that:

“The Union shall establish an internal market. It shall work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability … and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment.””

We have institutions to create and apply policies and those are called the legislative and the executive branch. Not central bank monetary policy.

Well, it’s always seemed to me if you handed the FED the power to distribute an equal UBI and tax carbon they could provide the needed stimulous with the UBI to counteract the deflationary effect of the carbon tax. Then raise the carbon tax as fast as is somewhat comfortable until emissions get under control.

I’m apprehensive about using monetary devices as de facto subsidies and taxes for industries favored and not.*

I get it- we live in world where carbon is bad. Therefore, central banks should increase the costs of using carbon. Increased costs reduce demand and use, so carbon is lowered and we avoid carbongeddon.

Ok, so far so good. But let’s remember that not all governments are green/gay loving liberal democracies with cosmopolitan views. Some, like Putin’s Russia, have a decidedly pro-traditional family stance. Others, like Modi’s India, have a tenancy of ethnic favoritism.

What if Russia’s central bank gave favorable financial treatment to anti-gay companies and groups? What if India’s central bank favored companies friendly with the BJP?

These developments could happen without the precedent of the ECB. But why give one?

If carbon is such a threat, convince the public and win elections. The feeling that a tiny minority sets the agenda for the majority is a powerful one driving the anti-establishment zeitgeist.

*There’s probably a reasonable argument that many central banks already favor certain industries and companies above others, but let’s keep things short here.

Carbon is not bad. Without carbon, life itself would be impossible.

Carbon is mal-distributed, too much in the air and ocean, too little in the soil and plant-soil systems. Reduce carbon-gas skydumping, increase plant-driven carbon-gas suckdown, store the suckdowned carbon in plants/soil/subsoil, and we get back to carbon balance.

Very interesting. Regarding collateral, banks and central banks have always liked real assets (buildings, factories…) more than anything. Will they count the carbron print of these, prefer other assets? I believe that by simply by using carbon taxes high enough this would do the trick reducing the real value of the “contaminating collateral” without the need to eliminate neutrality.

In other words, what this article states is tantamount to saying that current EU policy on carbon cap and trade is very inefficient.

I always thought the purchase of corporate bonds by central banks was only a temporary measure (“Quantitative Easing”). No?

I didn’t see the tax breaks for fossil fuels. Never mind the money laundering through venues like Panama (which has the dollar as its currency and no income tax), domestic petroleum producers get to write off the expenses of fracking, and the “depletion allowance” (about 15% off the top) so taxable income is smaller. The depletion allowance is theoretically enjoyed by mining generally, but 97% of it goes to petroleum producers.