By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She is currently writing a book about textile artisans.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) voted last week 3-1 to exempt small public companies – with annual revenues of less than $100 million – from the requirement that an independent outside auditor attest to the adequacy of the company’s internal control auditing provisions, as required by the Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX).

The proposal is now subject to a 60-day comment period, after which the Commission will decide whether to make it final.

The proposal is just the latest installment of SEC chairman Jay Clayton’s deregulatory agenda intended to encourage more companies to go public. As the WSJ noted in SEC Moves to Ease Audits for Smaller Companies:

SEC Chairman Jay Clayton has made it a priority to make it more attractive for companies to go public and framed Thursday’s proposal as a step toward that goal. It follows a move by the SEC last June to expand the number of companies that can make scaled-back disclosures to regulators that also was aimed at boosting interest in the public markets.

Biotech and health care companies are particular targets, according to Biospace, SEC Rule Change Will Ease Audit Requirements for Smaller Companies:

While the number of companies listed on the various stock exchanges has actually declined over the past 20 years, there are a number of high-profile companies set to announce IPOs this week or in the coming weeks. In the biotech and pharma world, a number of companies have rushed to list on the Nasdaq and other exchanges. Just this week, four biotech companies listed on the Nasdaq exchange. The companies, Maryland-based NextCure, South San Francisco-based Cortexyme, Canada-based Milestone Pharmaceuticals and Cambridge, Mass.-based Axcella all began listing on the exchange this week. The listing from these four companies followed nine companies that listed on the exchange in April, as well as seven in March. Still, the pace of biotech companies listing on the Nasdaq or other exchanges is not as robust as the previous year.

Like so many deregulatory chickens that have come to roost under Trump, this particular securities law egg was laid – or at the very least, incubated – during the administration of his predecessor (a topic I discussed at greater length in: Doubling Down on Deregulation: SEC Extends JOBS Act Benefit in Elusive Quest to Goose IPO Market). Don’t take my word for that either. As Yves wrote in this 2012 post, Why You Should Hate the “Jumpstart Obama’s Bucket Shops” Act.

Obama seems determined to roll back the few remaining elements of the New Deal. As we’ve recounted, he’s keen to cut Medicare and Social Security; he said as much in a dinner with leading conservative luminaries shortly after his inauguration. And his JOBS Act, which guts securities law protections on smaller stock offerings, is touted as a way to increase employment by helping to fund smaller businesses. In reality, the only jobs it is likely to create will be due to the resulting explosion in stock scamsters and bucket shop operators.

So, I suggest, that some of the history Clayton cites in his statement in support of the new proposal doesn’t reduce the inherent dangers. In other words, just because this isn’t the first step on a slippery slope, doesn’t mean it’s wise for the SEC to continue down this path (see chairman Jay Clayton, Statement at Open Meeting on Proposed Amendments to Sarbanes Oxley 404(b) Accelerated Filer Definition).

SOX History

Let me review some points for those who either didn’t watch the bankruptcies of Enron and WorldCom unfold in real time- or who may have forgotten relevant details. Recall the full title of that legislation – the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act – which enacted reforms intended to restore the confidence of investors whose faith had been deeply shaken by the accounting shenanigans revealed when the dot-com bubble burst.

For our purposes, two changes are key. First, SOX created a new system of internal control requirements, including a provision that CEO’s and CFOs personally certify company results. And second, just in case investors were not bowled over by those requirements, the legislation required an independent outside audit of the internal control provisions (SOX section 404 (b)).

Commisioner Robert J. Jackson’s Analysis

The SEC is operating at less than full strength, with only four commissioners – only one of whom is a Democrat. Of the agency’s five sitting commissioners, only three can be members of the same political party.

Commissioner Robert J. Jackson’s statement on the proposed rule change presented convincing analysis rebutting the rationale for the rule change. Press coverage of the SEC’s decision quotes a Jackson condemnation of fraud, but I found no discussion of the reasoning supporting his conclusion. It’s based on analysis, not ideology. As Jackson summarizes:

The proposal’s analysis of the costs of attestation is based on data that’s over a decade old, and the proposal makes no real attempt to assess the investor-protection benefits of gatekeepers in our markets. Having conducted my own analysis using data from today’s marketplace, it’s clear that this proposal has no apparent basis in evidence.

Allow me to discuss Jackson’s analysis at length here. Here’s the crux of his analysis:

The proposal rolls back 404(b) only for smaller companies on the theory that these are the firms for which the costs of attestation are most burdensome. But it’s equally possible that these are the firms—high-growth companies where the risk, and consequences, of fraud are greatest—where the benefits of the auditor’s presence are highest. The proposal uses decade-old data to examine the costs of attestation and makes no serious effort to evaluate the benefits. So my Office conducted an original analysis that shows, for two reasons, why this proposal has little basis in evidence from today’s marketplace.

Company Perspective. Jackson begins by looking at the problem from the perspective of company behavior. Here he demonstrates that the majority’s decision was based on data from 2004 that no longer seems valid.

Over to Jackson:

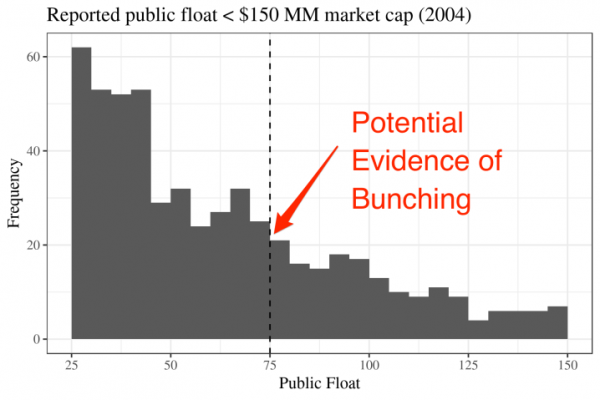

First, the proposal’s analysis of the costs of Section 404(b) relies heavily on a study using data from 2004 to show that companies with a public float under $75 million—the level under which auditor attestation is not required—seemed to “bunch” under that threshold. In other words, in 2004, companies and their investors found ways to keep their public float beneath the threshold—suggesting that the costs of 404(b) were meaningful for those companies (Jerri-Lynn here: citations omitted):

Figure 1. Potential “Bunching” of Public Float Under 404(b) Threshold Based on 2004 Data (citation omitted)

Source: Commissioner Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Figure 1. Potential “Bunching” of Public Float Under 404(b) Threshold Based on 2004 Data

Jackson concedes that if similar bunching were still apparent in today’s markets, that pattern might provide a basis of support for the latest proposal:

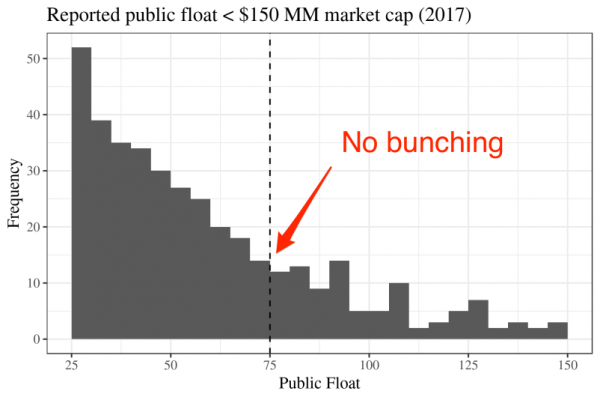

But it’s not. The proposal makes no effort to update these studies, simply claiming that old data is enough basis for new rules.So I replicated the 2004 study using today’s data and found no evidence of bunching (citations omitted; emphasis added):

Figure 2. No “Bunching” of Public Float Levels Based on 2017 Data

Source: Commissioner Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Figure 2. Potential “Bunching” of Public Float Under 404(b) Threshold Based on 2004 Data

Now, Jackson offers a possible explanation why the earlier bunching reflected in the 2004 data may have disappeared:

While the costs of Section 404(b) might have driven the decisions of small firms and their investors fifteen years ago, they don’t do so today. That makes sense, since Commissioners have worried aloud about these costs since SOX became law, and we have taken several steps to minimize them. That’s why, in 2011, the Office of our Chief Accountant examined the costs of the attestation requirement and reported to the Commission that there was no longer any “specific evidence that [any savings from rolling back 404(b)] would justify the loss of investor protections.” I cannot see why we should disregard our Staff’s careful recommendation without updating our evidence for today’s markets (citations omitted; emphasis added).

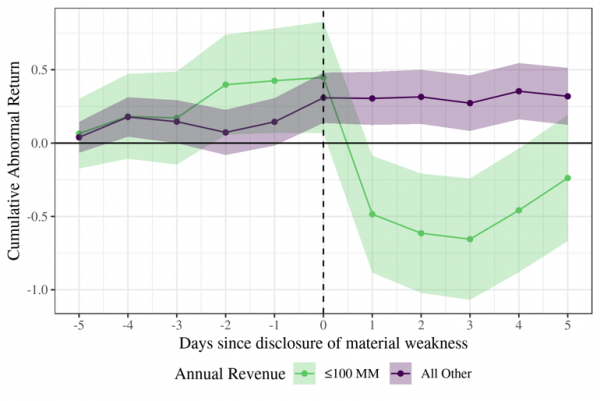

Investor Perspective. After looking at the problem of companies that might be inhibited from going public by the extant requirement, Jackson next analyzes the problem from the perspective of investors. Over to Jackson again:

Second, because this proposal makes no serious attempt to evaluate the benefits of attestation, my Office produced an original analysis on that question, too. We examined how investors react to news of an internal control failure in two groups of companies: those that would receive a rollback of 404(b) under today’s proposals and those who would not. The evidence is striking. The data show we are proposing today to roll back 404(b) for exactly the group of companies where investors care about the benefits of auditor attestation most (citations omitted; original emphasis):

Figure 3. Stock Price Reactions to Disclosures of Material Weakness

Source: Commissioner Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Figure 3. Potential “Bunching” of Public Float Under 404(b) Threshold Based on 2004 Data

Occupy the SEC: Latest Proposal “A Recipe for Disaster”

I reached out to Akshat Tewary, an attorney practicing in New Jersey, and President of Occupy the SEC, a nonprofit advocating for financial reform,for a comment on the SEC’s latest. Here’s his quick take:

… It’s a recipe for disaster for a number of reasons.

First, smaller reporting companies (SRCs) operate under the radar of the mainstream investing public, and are therefore more likely to suffer from deliberate financial manipulation. With relatively less scrutiny from institutional investors, SRCs already have every incentive to manipulate their numbers. This rule change would eliminate one of the key roadblocks (outside audits) to such predatory behavior.

Second, even where smaller reporting companies have the best of intentions, they have lesser operational capability vis-a-vis large public companies to avoid technical errors. Even if innocent, such errors can falsely sway the markets and mislead investors. And the fact that they are innocent means that securities fraud law, which requires scienter (legal willfulness), cannot serve as a deterrent. Here again the elimination of the auditing requirement sets the stage for mishap.

Proponents of this deregulatory move point to ongoing requirements under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, but despite it broad theoretical scope, SOX has not been effectively enforced by regulators. All signs continue to point towards a repeat of 2008.

The Bottom Line

Recently, I wrote about declining confidence in US regulators – the SEC, the FAA, FDA (EPA Says Glyphosate Is Safe, But Lawsuits Loom and Bayer’s Woes Mount).

I can’t help but think that rather than making it easier and cheaper to access securities markets, the SEC’s proposed rule might have the opposite effect. In fact, Jackson made this point:

While paying auditors isn’t free, neither is fraud. And fraud is more likely when insiders are less careful about controls. That’s why, when we roll back protections like these, we can expect the cost of capital to rise; investors will either diligence the risk of fraud themselves or require higher returns to protect against that risk. There’s a tradeoff; and hard evidence from the market, not ideological intuition, should tell us how to strike that balance.

For the cherry on top, pardon Bernie Madoff.

That should really emphasize what time it is.

Years ago, when I asked an acquaintance why the particular JUF that she worked for wasn’t scammed by Madoff, her reply was simple: “We require audited financials before we will work with someone.”

Speaking of accounting fraud, the liabilities of banks are for fiat – which the non-bank private sector may not use* except for increasingly irrelevant physical fiat, aka “cash”.

So the liabilities of the banks toward the non-bank private sector are largely a sham.

So how can we have an honest economy with sham accounting?

*Only depository institutions, aka “the banks”, may use fiat in account form – via accounts at the Central Bank – not individual citizens, State and local governments, etc. Thus the banks have a government given monopoly on the use of fiat except for mere physical fiat.

And why I keep .01 in the bank.

Theranos.

How many Elizabeth Holmes “mini-me’s” can be created?

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/08/business/dealbook/elizabeth-holmes-theranos-trial.html/

“Elizabeth Holmes’s Possible Defense in Theranos Case: Put the Government on Trial”

Trial coming…

TL;DR Lesson from Theranos: if you’re going to commit a fraud, make it big and defraud people who’ll be too embarrassed to admit that they were grifted and more than happy to sweep it under the news cycle.

This is great news for securities fraud attorneys. Everyone else, not so much.