Yves here. It’s good to see a former health care industry executive provide detail to why pricing, particularly for hospital services, is such a clusterfuck. Of course, this is far from the only reason US health care is so costly yet produces lousy results by international standards. Another is that the US pays doctor on the piecework model.

By J.B. Silvers, Professor of Health Finance, Weatherhead School of Management & School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University. Originally published at The Conversation

The news is full of stories about monumental surprise hospital bills, sky-high drug prices and patients going bankrupt. The government’s approach to addressing this, via an executive order that President Trump signed June 24, 2019, is to make hospitals disclose prices, including negotiated rates with insurers, so that patients supposedly can comparison shop. But this is fool’s gold – information that doesn’t address the real question about why these prices are so high in the first place.

I know from my time as an academic researcher, hospital board member, adviser to Congress and health insurance CEO that the problems in health care are far deeper than just knowledge about hospital charges that few will ever pay.

While it is easy to blame greedy pharmaceutical manufacturers, health insurers and hospital executives, the problem comes from the very nature of our confused system. Who actually benefits from these high prices and why do they persist? Is it just greed, or something endemic in the system?

Should the EOB be DOA?

Many in the health care system, including hospitals, doctors and insurers, are complicit in this confusing mess, although all can justify their individual actions.

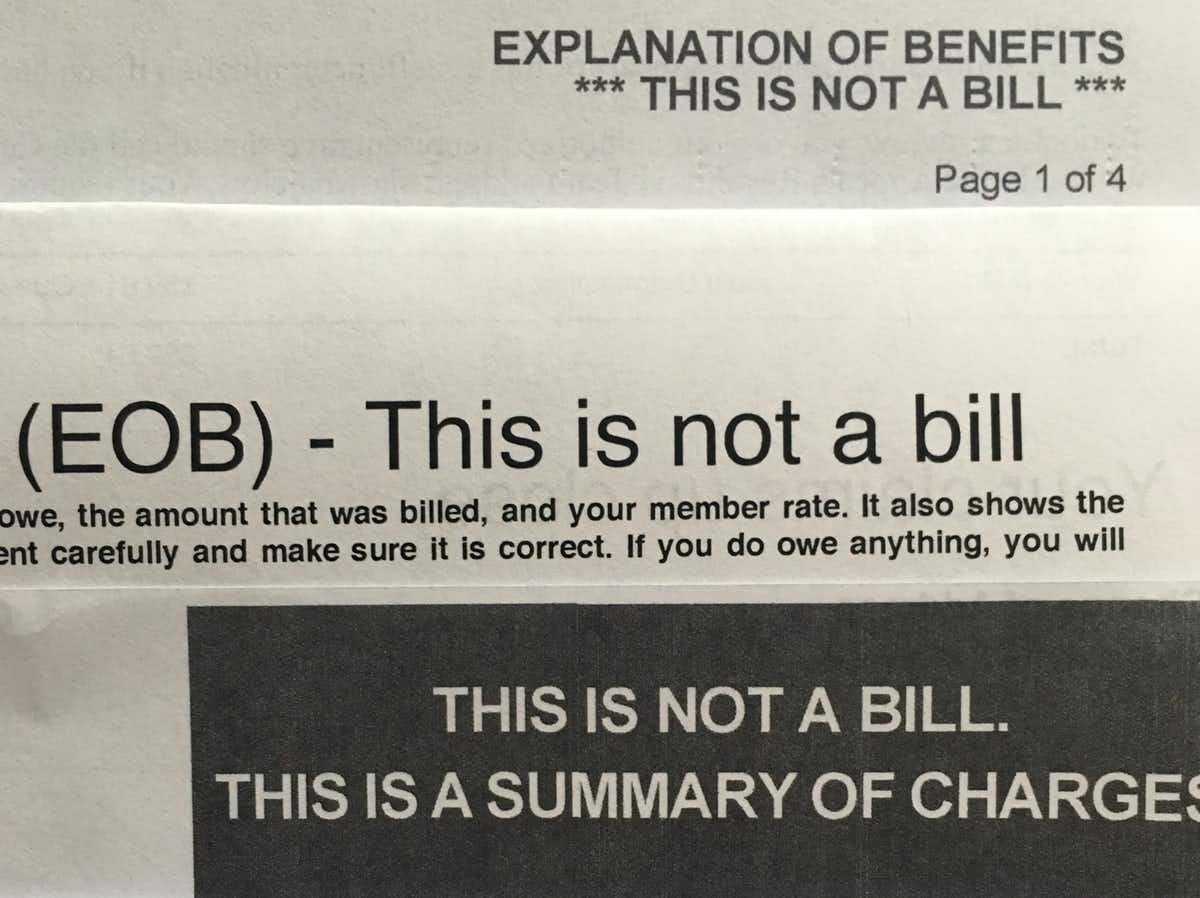

The confusion begins for the patient when he or she receives an explanation of benefit (EOB). This typically says it is “Not a Bill,” although it really looks like one. What it actually shows is incredibly high provider prices and an equally implausible discount. The bottom line lists the actual payment and the amount the patient owes. Patients are supposed to be grateful for the discounts after they recover from the sticker shock of the listed price.

When a service is provided out-of-network, or is not covered at all, or the person doesn’t have insurance, the patient is supposed to pay this full amount. Such “surprise bills” typically come to those least prepared to pay and, as a result, providers typically recover very little. So no one wins, except the collection agency and the lawyers.

I believe the standard EOB is the beginning of unnecessary complexity that leads to higher prices and an impossibly flawed market where shopping can never really work properly.

This ridiculous situation actually starts with insurance companies selling policies to ill-informed employers who don’t understand health care but effectively are the purchasers. Employers hire brokers and consultants to collect proposals from insurers; by some estimates, as many as 50 million people in the U.S. are covered by such plans.

These proposals frequently focus on the size of the discount from providers’ list prices as an indicator of how much the employer can save. The overall total cost or coverage is more important, but harder to estimate, since it depends on actual care delivered to employees. The unrecognized incentive for providers and insurers is to increase prices in order to increase the size of the discount.

I have actually seen cases where the insurer requests higher list prices from a provider to pump up the discount they can report to employers. This is crazy.

Stop the Madness

One solution to this mess would be to require uniform prices by all providers to all purchasers. Maryland has a form of this “all-payer” system where everyone pays the same under rate regulation or negotiation. France, Germany, Japan and the Netherlands also use this form of control.

Benchmark pricing against what Medicare pays would do something similar, with everyone paying a fixed percent of these nationally regulated rates. This would blunt the ability of hospitals to arbitrarily jack up list charges and negotiate contract prices with insurers based on relative market power.

Unfortunately for consumers, such rate setting may be a political “bridge too far.” While some progressives might like regulation, conservatives likely will not because it challenges their faith in the superiority of free-market negotiations around prices.

And it might dampen innovation and even competition, depending on how realistic and flexible the regulators are in responding to new technology, alternative procedures, quality differentials and consumer demands – the decisions where markets are supposed work well.

Can Price Competition Work?

The overarching question is whether patients and employers can ever do comparison shopping effectively. Clearly for many things, there can be no head-to-head choice. Trauma, highly complex surgery and other care cannot be predicted ahead of time or standardized to fit a consumer market model.

However, some things can be compared. Insurers now routinely let consumers know if a test or image could be done for less elsewhere. Perhaps comparing just a few services as an overall cost indicator is the best we can do.

But it may also be possible to determine overall relative bargains for a typical package of care to guide choices. My Cleveland hospital, MetroHealth System, manages Medicaid patients for a total cost which is 29% less than when they wander around without a medical home. This is a meaningful difference.

A first step towards comparison shopping might be eliminating the EOB as we know it. Rather than showing meaningless list prices, it would be more revealing if hospitals and insurers had to disclose their actual payment terms.

An alternative benchmark might be to provide health care consumers with a range of contract rates or the Medicare rate for a service. Then the difference between what you and others actually pay could be useful in comparing providers and insurers.

Those who long for a total overhaul of our system through “Medicare for All” or its variants, such as many Democrats vying for the nomination,, will still have to deal with the question of how to contract and pay for all these moving parts. The temptation will be toward simple solutions involving prices, discounts and rate regulation – still, I believe, effectively a pursuit of fool’s gold.

Here’s another recent medical horror story in the USA- https://youtu.be/5tMtX03u3aM

That’s it right there. Since I first had an appendectomy at age 45, 17years ago, the healthcare system has gotten worse and more expensive every year.

The question everyone living in the US needs to ask themselves is, are you willing to risk bankruptcy by continuing to live here?

Because the possibility of actual, real change seems as remote as ever. The number of outrages and horror stories doesn’t seem to make any difference.

Costs and pricing and incentives and discounts are probably interesting to wonks and administrators, as this guy is. But I don’t see any reason people who are being treated by the healthcare system need to get into all these weeds.

When I drive on a road, I don’t need to know the price of asphalt or how much it costs to rent paving equipment. I just drive on the frigging road. *Someone* needs to know these things and make sure the finances are sound and fair to both the city and the contractors, of course. But that is not a user’s responsibility. If individual drivers got a detailed bill each time they drove somewhere, filled with list prices and discounts and driver’s responsibilities (“this is not a bill”!), we would conclude our road management system should be replaced.

One of the unfortunate results of neoliberalism’s let’s-make-everything-a-market dogma is this kind of nonsense, where we are all supposed to be “smart consumers” and make thousands of “informed decisions” on any and all matters. Then if things turn out badly, it’s obviously our fault.

Smart. There’s that word again.

They never admit/realize that there are very few “markets” such as are discussed in Econ 101. All procucers produce exactly the same product, so the only difference is price. There is no branding, so the only difference is price. There are so many producers that no one can affect the price. There are so many consumers that no one can affect price. Entry into production is costless, so if there’s a way to produce a product for less millions of producers will immediately enter the market. I think when I took Econ 101 the instructor mentioned that maybe the soybean market would fit that model, but even in those days there was a local monopoly the farmers had to sell to.

The value in knowing the prices was to compare them GLOBALLY.

Everybody seems to have forgotten that.

Patients are NOT consumers who shop for a product!

Bingo. What is the phrase “consumer demands” doing in an article about health care? The medical industry likes to pretend that patients are demanding all the latest expensive bells and whistles whereas the “consumers” are merely patients who want to be cured. Trying to pretend that medicine is a business is insane and I doubt even “conservatives” other than conservative doctors and hospital owners want things to be the way they are. What we really have are a group of people who look at the health care industry and see a giant pile of money.

J.B. Silvers of CWRU: long a defender of the health care status quo and enemy of single-payer Medicare for All. I don’t think he ever met a reform he didn’t think was “a bridge too far.”

Thanks for pointing this out!

Yep. This is a dead give away:

“And it might dampen innovation and even competition, depending on how realistic and flexible the regulators are in responding to new technology, alternative procedures, quality differentials and consumer demands – the decisions where markets are supposed work well.”

The major innovation in Health Care is how much can they raise prices.

Healthcare is a commodity, with little differentiation between providers.

Part of the problem is the unspoken part of a Doctor’s education: How to repay $500,000 of student debt. Eliminate that debt, and cost will fall.

There may be little differentiation between providers, but that’s irrelevant. The variation is between the patients. In a market the product is undifferentiated. In health care each patient requires different treatment. Secondly, in a market price is undifferentiated. Every producer charges exactly the same price. In health care what a small town doctor charges in his clinic will be very different from what is charged for the same care provided in a university teaching hospital. Then of course there is the point that in many, perhaps most, cases the patient has no say in where they will be treated. Trying to treat health care as a “free” or competitive market is absurd. Competition can occur among health insurers, but even there the products are strongly differentiated and so complex it’s nearly impossible to analyze the differences.

I believe that is utterly contrary to human nature.

The all-payer system is likely the optimal system since the nature of health care markets with time sensitive, inelastic demand, high switching costs and information asymmetry all mitigate the benefits of price competition.

There should be no need whatsoever to raise taxes with a medicare for all system. US gov’t entities already spend c. 8% of GDP on healthcare, which is equivalent to what other industrialized countries spend on universal care.

Sick Around the World is still one of the best summaries of what other systems do.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/sick-around-the-world-con_b_158559

Tenets that we ought to consider:

1. All-payer

2. Doctors say what happens not insurance companies

3. Insurance is not-for-profit

4. Universal/guaranteed issue insurance with a single payer or voucher system

5. Risk adjustment for higher risk insurance pools

The guaranteed issue is a good addition. However, it needs to be tempered with a clause, such as what we have here in NJ. Even before ACA this was a ‘guaranteed issue’ state, no one can be declined. However, if you’re without coverage for more than 61 days, then the insurer can impose a pre-existing conditions clause for one year. This is to prevent someone buying insurance only when they find out that they need it, essentially being a freeloader on the system, taking advantage of the money pool that others have contributed to but they have not.

This is probably the only case where I am fully in favor of globalization. The best solution for our health care mess is to allow all the associations, doctors, administrators, insurance companies, drug companies, etc. to go apply for work elsewhere, because we can no longer put up with them. Send their resumes off to India, the UK, China, maybe Australia or Canada, maybe Cuba or Mexico, everywhere medical care providers are in short supply. Good providers, of course. And we here in the US can open our doors to providers from other countries. We can also make it a goal to graduate more doctors and specialists from our medical schools, enough to bring costs down. Say we have twice the number of doctors and good hospitals we now have – that would help. After all it’s good old American competition. Then just for ducks we should evaluate what medical services are worth by how effective they are. If you are properly fixed up and your good health is quickly re-established, and you are provided the best care to keep you healthy, good drugs, etc,. then those services should establish the benchmark price. But if it is pointless “health care” and does nothing to improve your health or that of the nation as a whole it should be totally “discounted”. So what is it worth? Is it worth losing your home? Is it worth losing your campaign donation? Is it worth destroying this country? Is it worth incurring the deep hatred of every citizen in the USA? And whatever price is established for this good care should be one that doesn’t violate human decency. And that alone would make all the ridiculous bookkeeping and the shell game of the medical industry obsolete. They should get what they deserve.

Trauma, highly complex surgery and other care cannot be predicted ahead of time or standardized to fit a consumer market model

Sure, transparency pricing for those shopping for elective procedures. How about ER patients from unconscious gun shot wounds, broken bones to heart attacks? I can see the intake administrators handing patients a leaflet with prices and please sign the informed consent legal agreement (for the hospital’s protection not the patients) for services. Its another government do nothing round around riding in tandem with the Funeral Industry.

That culture of secrecy persists in what’s now known as the death care industry. A kind of strategic ambiguity about prices is part of the business model.

A federal regulation called the Funeral Rule is supposed to protect consumers who have lost loved ones. Among other things, it requires funeral businesses to provide potential customers with clear price information. But an NPR investigation found that the rule goes only so far in protecting consumers, and that its promise of transparency often goes unfulfilled.

Howard, a lawyer specializing in consumer issues for the Center for Public Interest Law at the University of San Diego and group’s head litigator and lobbyist, spent an eight-hour day just to get a solid list of what funeral services were offered by nearby funeral establishments and how much they cost for his father’s impending death.

Sticker shock for hospital/doctor bills onto Sticker Shock at Funeral Homes: The average price of a funeral in the USA is currently between $7–10,000. Do you know WHY it is so high? Do you know what you are required to purchase and what is just an option? Do you know that many funeral homes love when you walk in with an insurance policy and no idea what you should be spending? Why is this?

On average, families that enter a funeral home for the first time after the loss of a loved one will spend approximately 35–60% MORE than they would if they had been prepared. The funeral and cemetery staff knows this and many are trained to capitalize on your grief.

Bonuses, monthly contests, and corporate pressure are heaped on funeral and cemetery staff to keep the average profits high. A funeral director with a conscience and who helps too many families keep their costs low will soon find him or herself out of a job.

The American Way of Death is an exposé of abuses in the funeral home industry in the United States, written by Jessica Mitford and published in 1963.

From Wikipedia.

There was a thread on this site recently about the importance of making these decisions well before the need arises. My sister-in-law was seriously ill for 30 years, pronounced terminal for a year and on hospice for three weeks. After she died, the family went shopping for a burial site and funeral home services. No need to comment on the absurdity.

Speaking of hospitals and expenses the hospital I go to as an out patient is closing in Philadelphia in around 90 days or sooner. It been losing money for years. Rumor has it they will replace it with expensive condos. This hospital takes a lot of patients who have little or no insurance. Guess they will have to find another hospital like myself.

https://www.inquirer.com/business/hahneman-hospital-philadelphia-closing-20190626.html