By Amahia Mallea, Associate Professor of History, Drake University. Originally published at The Conversation

New Orleans averted disaster this month when tropical storm Barry delivered less rain in the Crescent City than forecasters originally feared. But Barry’s slog through Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee and Missouri is just the latest event in a year that has tested levees across the central U.S.

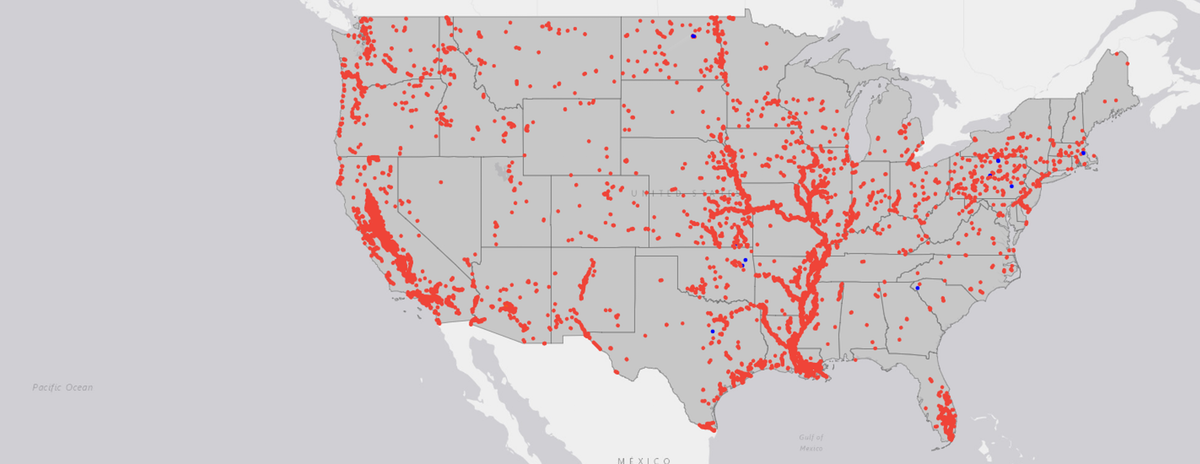

Many U.S. cities rely on levees for protection from floods. There are more than 100,000 miles of levees nationwide, in all 50 states and one of every five counties. Most of them seriously need repair: Levees received a D on the American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2018 national infrastructure report card.

Levees shield farms and towns from flooding, but they also create risk. When rivers rise, they can’t naturally spread out in the floodplain as they did in the pre-flood control era. Instead, they flow harder and faster and send more water downstream.

And climate models show that flood risks are increasing. During this year’s unusually wet winter and spring, dozens of levees on the Missouri, Mississippi and Arkansas rivers were overtopped or breached by floodwaters. Across the central U.S., rivers are becoming increasingly hard to control.

Levees exist in one out of every five U.S. counties. USACE

Remaking the Missouri

In my book, “A River in the City of Fountains,” I describe the complexities of flood control in Kansas City, which sits at the junction of the Missouri and Kansas rivers.

The Missouri, the larger of these two, is America’s longest river, rising in Montana’s Rocky Mountains and flowing east and south for 2,341 miles until it joins the Mississippi River north of St. Louis. Historically it was wide and shallow, full of sand bars and snags that created challenges for steamboats.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Kansas City business leaders began lobbying for federal navigation subsidies to counter the influence of the railroads. Until the river could be narrowed and deepened, navigation was unreliable. And without levees, industry in the floodplain was at risk.

Major floods inundated Kansas City in 1903, 1908, 1943 and 1951, leaving thousands homeless and causing heavy economic damage. These disasters convinced civic leaders that more than piecemeal navigation and flood control projects along the lower Missouri were needed.

In 1944 they got their wish when Congress passed the Flood Control Act, which authorized construction of dozens of dams nationwide. One section of the bill, the Missouri Basin Plan, sought to convert the entire Missouri into what historian Donald Worster calls an “ornate hydraulic regime,” with five upstream dams for hydroelectric power, irrigation and recreation, as well as levees and a navigable barge channel from Sioux City to St. Louis.

Over the next decade engineers built levees and straightened and dredged the river channel. Upstream dams curbed the Missouri’s spring rise. In August 1955, Life Magazine reported that “U.S. engineers have finally clinched their victory over the rampaging Missouri River. Flood control … is already bringing prosperity to the valley it drains.”

‘Achelous and Hercules,’ painted by Thomas Hart Benton in 1947, evokes a struggle between Hercules and Achelous, the Greek river god. Benton, a Kansas City native, saw the legend as a parable for efforts to tame the Missouri River.Smithsonian American Art Museum, CC BY-ND

The Limits of Levees

Today Kansas City and many other U.S. river towns are fortified behind levees and floodwalls, but faith in the idea of engineered flood control is starting to erode.

Disastrous Midwest flooding in the summer of 1993, which killed 50 people and caused US$15 billion in damages, showed the limitations of this strategy. Floodwaters rose to unprecedented levels, eventually breaching or overtopping more than 1,000 levees.

After the waters ebbed, federal and state officials paid to move some homes and communities off floodplains to higher ground. However, this trend quickly reversed. By 2008, Missouri had authorized more than $2 billion of new development in zones that were flooded in 1993.

Many Kansas City residents still believe that higher, stronger levees will hold back future floods, and Congress has authorized millions of dollars to build them. But experienced engineers like retired Army Brigadier General Gerald Galloway, who coauthored a federal government assessment of the 1993 floods, warn that “there’s no such thing as absolute protection.”

For their part, many scientists and engineers have found that levees can exacerbate floods by pushing river waters to new heights. One 2018 study estimated that about 75% of increases in the magnitude of 100-year floods on the lower Mississippi River over the past 500 years could be attributed to river engineering.

What about commercial benefits from channeling rivers? Kansas City is still an economic hub, but railroads and highways have been more important than barges. The Missouri carries only a fraction of the tonnage shipped on other navigable rivers, such as the Mississippi, even though its channel has been expensively built and maintained for over 100 years.

Rethinking River Control

Levees also constrain cities’ relationships with rivers, walling off any connections for purposes other than commerce. Author William Least Heat-Moon captured this paradox when he traveled across the U.S. by boat in the late 1990s and observed that “Kansas City, born of the Missouri, has turned away from its great genetrix more than almost any other river city in America.”

More recently, however, Kansas City has begun to remember its interest and love for the Missouri. Riverside development and public spaces are fostering new physical and cultural interfaces with the river.

In my view, this year’s floods should lead to more of this kind of rethinking. River towns can start by restricting floodplain development so that people and property will not be in harm’s way. This will create space for rivers to spill over in flood season, reducing risks downstream. Proposals to raise and improve levees should be required to take climate change and related flooding risks into account.

Davenport, Iowa has embraced this approach. With a population of over 102,000, it is the largest U.S. river city without levees or a permanent floodwall. Instead Davenport has emphasized adapting to flooding by increasing public green spaces in the flood zone and elevating buildings that flank the Mississippi River.

Kansas City and other towns could advance this discussion by moving beyond strictly commercial visions of their waterways and considering this question: What does a healthy river of the future look like?

“What does a healthy river of the future look like?”

Good question when you are talking about the Mississippi river which wants to meander all over the landscape. In one of Mark Twain’s books, he talks about being on a river boat when the captain called him over to point out a town that the river had mostly demolished by shifting its course. Remnants of the doomed town were still visible on the banks of the river. Being neighbours with that river will always be in the end, be at the sufferance of that river.

RevKev: The book you reference is Life On the Mississippi, and it is hands-down my favorite Mark Twain book, in part because the Fourth Wall that lies between Mark Twain and Sam Clemens is nearly breached. One of the snarkier passages from the chapter you referenced:

Thanks for posting this, Yves. As a Davenport native, I’ve become accustomed to my hometown’s mention every time the subject of flooding and flood control comes up. I long ago grew tired of hearing how backwards Davenport was for not building a levee; those catcalls were especially pronounced during the 1993 flood. This is the first article I’ve ever read that compared the annual cost of maintaining a levee to the damage caused by flooding, particularly on the Mississippi. And yes, the construction of levees simply makes the underlying problem worse. I believe the name of the Illinois town that was obliterated in 1993 when its levee failed was Keithsburg. I wouldn’t want to visit such a horror on any town. It’s nice to see the world finally catching up.

Also an odd flashback to see Mary Ellen Chamberlin quoted in the article. She was a big mover and shaker in Democrat politics in Davenport in the 70s and 80s; I’m not positive but she may be a descendant of a family of very powerful local Democrats (a prominent attorney named Chamberlin was very active in Democrat politics in the 1890s).

A good article about an issue that is hiding in plain sight. One such landform is the levee on the Sacramento River, that blends into the background. In many areas it is right next to numerous residential and commercial areas. If that levee breaches, surf’s up.

The average person may not give much thought to levees, and older folk might recall a song, lyric or two that referenced them:

Drove my Chevy to the levee – Don McLean

When the levee breaks – Led Zeppelin

Thank you, OTS, for the Don McLean reminder. Enjoy this, from the banks of the Grand River in Michigan!

When the Levee Breaks was a blues song about the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927, written and recorded in 1929 by Kansas Joe McCoy and Memphis Minnie (she was living in the Mississippi Delta in 1927 — an area between the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers, not the mouth at the Gulf of Mexico).

I believe it was John Mayall who started the trend of so many British bands recording covers of blues songs by black artists. Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page both played briefly with Mayall in the mid-’60s; Cream and Led Zeppelin both had such covers in their early albums. In 2004 Clapton recorded a whole album of songs by the legendary black guitarist Robert Johnson. The accompanying video documentary of those sessions is absolutely AWESOME!

And then there is Louisiana 1927 by Randy Newman.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MGs2iLoDUYE

This is a topic I briefly summarized when Lambert posted about it a few months ago. I will only restate my reading recommendations here: Luna Leopold, The Flood Control Controversy (1953) and A View of the River (1994, 2006 in paperback). Both books require some familiarity with college level science.

Luna Leopold worked for the USGS in his early days eventually becoming an esteemed (revered?) Professor at UC Berkeley. His books can be viewed on Amazon and ordered through your local bookstore (or library). What you’ll discover is that “business” outweighs science when it comes to water (fluvial or marine).

BTW, on another reflection of These Modern Times:

> In August 1955, Life Magazine reported that “U.S. engineers have finally clinched their victory over the rampaging Missouri River.

It may not have been a good idea. But it was done – and the US population was half what it is now. They found the money and manpower to rebuild the whole stupid river then and we can’t do crap today except drop a MOAB which barely disturbs the vegetation.

And people talk about “how will we relocate from Global Warming” — but we can’t even do the type of projects that we could 60 years ago. The answer is not “how we will”, but simply “we won’t”.

In the Netherlands, we’ve added other options on top of using levees. After a major threat to a number of river levees way back when (90’s?) (I prefer to use the typical Dutch term dijk by the way), we’ve selected certain areas as potential overflow areas. If the water rises too much, then certain areas are allowed to flood, sparing other areas. If the Netherlands, which is densely populated, can do this, then the US, which is way less populated, can do that as well. We’ve learned not to tightly “bind” a river to it’s course. It might be time for countries to learn that lesson as well. We’ve also limited building anything in areas just outside of the river levees (the so called “uiterwaarden”).

If anyone knows how to live in the floodplain, and even below sea level, it’s the Dutch, so thanks for weighing in.

I have a personal stake in this, because we live in the floodplain, on a small tributary of the Willamette. The main part of our floor (a slab on grade) is just two inches above the 100-year flood line – though that line is rather speculative here. In 1996, there were three feet of water running across our driveway, in a swale between our property and the street. I didn’t even notice that dip in the driveway until it was full of water. The flood that year came within about 20 feet, and a couple of vertical inches, of the house. However, that’s a tremendous amount of water.

Last winter, the Willamette flooded the area east of town on the other side, but our river was high but not unusually so. It practically stopped flowing, backed up by the nearby confluence.

When we moved in, I talked about making a berm all the way around the house; a foot or so could make a big difference. But it’s harder than it sounds, so I never did. The garden in front is now high enough to make a difference, just from cultivation.

Apparently there was discussion at one time of a levee to protect our neighborhood; as proposed by the Corps, it would have cut across our back field, separating us from the river. No one thought it was worthwhile. Apparently that’s just as well; any kind of fill or barrier just throws the flood onto someone else = when it works at all.

Incidentally, flood insurance is forbiddingly expensive.

In 1600 or so, there was a Chinese Governor who designed and built flood control works on the Yangtze.river. The were a series of walls, each farther from the river that the next, and each higher than the next, all stone-lined, so that as the river flood became larger and larger the river became wider and wider. The area between walls would still be suitable for farming, with the understanding that in some years the crop would be under water.

Smaller than Davenport, Rapid City, SD (pop 74,421) suffered a catastrophic flood in 1972 in which 238 people died when torrential rains led to the failure of Canyon Lake Dam and a flash flood down Rapid Creek. It was horrendous. It didn’t just flood, it took out houses right off their foundations. Instead of building levees, the city cleared the floodplain, prohibited rebuilding, and installed a number of parks, including Memorial Park downtown along the banks of Rapid Creek. The city took some heat at the time, but the change was very beneficial in the long run.

I don’t think that it is as simple as levees=bad but rather the stupidity of building flood control and then not maintaining them as well as building entire neighborhoods in designated floodplains; it’s telling when people get mad when dams and levees break because no money was spent on maintenance, those floodplains get flooded, or (and this is precious) as in New Orleans the crews manning pumps for the wealthy part of town stayed while the pumps for the Ninth Ward were abandoned.

Yet, whenever the budget comes up and the opportunity to do all the work needed, people scream about their taxes even when it is Washington doing it, never mind the local governments.

It’s like the lack of any official long term economic policy by the federal government supposedly because Markets!, but the semi-official policy, complete with tax credits, for off shoring whole industries happens anyway. One year or decade generous funding for infrastructure is there and then it’s not. So things fail and people die, with those with money getting more help than those without.

What should actually happen is people should be resettled out of a flood plane. This would take a long time but is probably the only viable solution. A reason we have more frequent floods is development. Land has been cleared for several reasons. One is farming . Also you have highways and parking lots. Mother nature used to act as a barrier against flooding. Now when it rains the water quickly runs off into streams and rivers, causing flood conditions. A start would be to not let people settle in a flood plane.

“When the Levee Breaks” was originally written right after the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. That was when the wealthier white communities deliberately broke levees flooding poorer communities of blacks and Cajuns. That was a major factor in the great migration north that ended up with significant black populations moving as far north as Chicago in the late 20s and 30s. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Mississippi_Flood_of_1927

In Minneapolis/St Paul there is talk of removing the two lock-and-dams, returning the river to the whitewater it long was. Some of the argument haas been economic, such that 7 miles of whitewater through a major metropolitan area would be unprecedented and a boon to tourism. But local and Fed leadership is still stuck in 20th century economic thinking, even though the dams cost more to maintain than the shipping they allow benefits the economy.

re: “When rivers rise, they can’t naturally spread out in the floodplain as they did in the pre-flood control era. Instead, they flow harder and faster and send more water downstream.”

moreover, that lack of floodplain flooding prevents aquifers from being recharged as they normally would…

Couple of things. Almost all regulation of construction is based on FEMA published Insurance Maps. In preparing these maps, FEMA’s standard does not consider future development, rather it is a snapshot of an existing land use, usually several years before the map is published, and which can remain in effect for a decade or more with potentially obsolete data still depicted on the maps. When this is done in developing areas, or rapidly developing areas as Houston was, the intended flood protection is doomed to fail.

Secondly, FEMA standards, and most standards in communities, have long allowed for filling in floodplains, thereby reducing their storage capacity to hold large volumes of water (levees have the same effect) which either move more rapidly downstream, or stack water higher upstream, either which results in unexpected, or more frequent, flooding.

Lastly, the historical records for rainfalls and flood events used for a century to derive the statistical rainfall probabilities are obsolete, as climate change has dramatically altered them in past 20 years, and with the acceleration of warming they will remain in flux, for decades.

Given the vast amount of property developed under obsolete actuarial risk analyses, it is likely that the current National Flood Insurance Program will soon be unsustainable in total, as it is for many specific areas today.

Federal flood insurance is not inexpensive, but market rates for similar coverage, if it is even offered, are much higher. Federal flood insurance is available in communities that have adopted FEMA requirements into their codes. Areas not covered by a participating community will pay much more, in my experience typically at least 5 times higher. In the areas highest risk, repetitive loss areas, market rates can be as high as 20 percent of the value of a structure, per year. In these cases most owners don’t bother with insurance and instead rely on state and federal disaster funds when the worst eventually happens.