By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She is currently writing a book about textile artisans.

Climate change lawsuits have now been filed in at least twenty-eight countries, according to a new report Global trends in climate change litigation: 2019 snapshot, published last week by the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics.

I was alerted to this report by an account in the excellent Climate Liability News, Climate Litigation Has Become a Global Trend, New Report Shows.

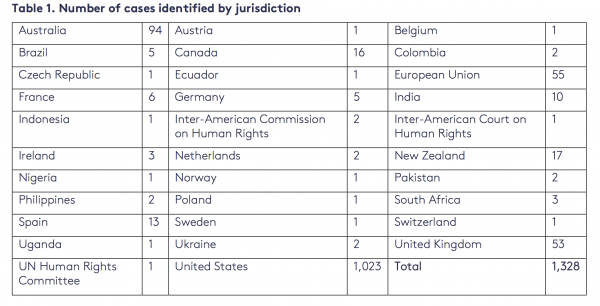

The first such lawsuit was filed in 1990. More than three-quarters of these lawsuits have been filed in the US, where as of May 2019, 1,023 cases have been filed(report, p.2). This litigation is at present concentrated not only in the US, but also in other high-income countries, including Australia, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Canada, and Spain (see Table 1 below).

But this phenomenon is not limited to wealthy countries alone. The report noted that “despite significant capacity constraints, the number of legal cases in low- and middle-income countries has been growing in quantity and importance”:

These include cases in Pakistan, India, the Philippines, Indonesia, South Africa, Colombia and Brazil. Litigants in these cases are seeking to hold governments to account for implementation and enforcement of existing mitigation and adaptation goals, embedding concerns about climate change in wider disputes over constitutional rights, environmental protection, land use, disaster management and natural resource conservation (Peel and Lin, forthcoming).

Climate change litigation in low- and middle-income countries has already seen initial positive and innovative outcomes. These include the recognition of human rights as a legitimate basis for holding government to account for climate change (Ashgar Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan – see Box 4); recognition of a non-human entity as the subject of rights (Future Generations v. Ministry of the Environment and Others); and recognition of climate change as a relevant consideration in environmental planning (EarthLife Africa Johannesburg v. Minister of Environmental Affairs and Others).

Governments comprise the bulk of defendants in these lawsuits, brought by citizens, corporations, and NGOs; but plaintiffs are increasingly targeting companies in actions brought by cities and states, and activist shareholders and investors.

Source: Global trends in climate change litigation: 2019 snapshot, p. 3; Sources: Authors, using www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/climate-change-laws-of-the-world/ and http://climatecasechart.com/us-climate-change-litigation/

Trump Trend

The climate debate has heated up significantly under the Trump administration – and lawsuits have followed. According to the report:

Since the start of its mandate, the Trump Administration has undertaken an extensive programme of climate change deregulation (as shown by Sabin’s climate deregulation tracker at http://columbiaclimatelaw.com/resources/climate-deregulation-tracker/).

To challenge these efforts, over 20 suits have defended the federal climate policies of the previous administration. They have raised a variety of claims under statutory, administrative and constitutional law. Plaintiffs have also brought lawsuits under the Freedom of Information Act, seeking records from the Trump Administration on its climate-related actions and communications. To date, more than two-and-a-half years into the Trump Administration, no rollback of a climate regulation brought before the courts has survived a legal challenge.

Lawsuits seeking to enforce consideration of climate change as part of environmental review and permitting – both in terms of a project’s potential greenhouse gas emissions and how climate change impacts may affect a decision or project – continue to be a dominant trend. Many of these suits often challenge fossil fuel extraction and infrastructure projects.

In the face of federal opposition to climate policy, plaintiffs continue to bring innovative claims. More than a dozen local governments, one state, and a trade association have filed lawsuits against major fossil fuel companies, alleging that they have continued to produce fossil fuels while knowingly concealing the climate risks. Plaintiffs also continue to argue before state and federal courts that the sovereign’s responsibility to preserve the integrity of natural resources in its territory – the public trust doctrine – requires it to address climate change. In effect (and explicitly in some cases), these plaintiffs are seeking recognition of a right to a stable climate (report. p. 6).

Not all lawsuits are intended to establish liability for climate change; some are instead designed to buttress climate change deregulation. According to the report:

However, industry, conservative NGOs and others have also brought suits to support climate change deregulation, reduce climate protections generally or at the project level, and to target climate protection supporters. Lawsuits have also challenged the novel efforts of states like California, Illinois, New York and Connecticut, which are creatively discouraging fossil fuel use. These suits claim that these states are overstepping their legal bounds (report. p. 6).

Lawsuits Against Private Corporations

Cases against private defendants fall into at least three categories. The first those seeks to hold private companies to account for loss and damage due to climate change:

In the past year a spate of public nuisance suits against fossil fuel companies has sought damages potentially amounting to billions of dollars to cover the costs of adaptation (e.g. the cost of infrastructure to protect against sea level rise and other physical impacts of climate change). These lawsuits are also novel in that they were brought by US state governments and municipalities such as the State of Rhode Island, and the cities of New York, San Francisco and Oakland, rather than citizens or NGOs. The plaintiffs allege that fossil fuel companies continued to produce fossil fuels while knowingly concealing the climate risks (report p. 8).

The second focuses on investment angles: either alleging that a company (e.g., Shell), failed to incorporate climate risks in its investments, or alleging that a company (e.g., Exxon-Mobil) misled investors by understating how much risk climate change poses to the company’s assets. And several cases in a third category seek to require better, more complete disclosure of climate risk to investors and shareholders (report, p.9).

Litigation Awkward and Inefficient Mechanism for Arresting or Mitigating Climate Change

As the climate crisis accelerates, climate change litigation will persist as one of many tactics to address the problem. Yet it is by no means an ideal mechanism for tackling these issues. According to the report:

Moreover, litigation is often a lengthy, costly and risky process, and in certain contexts it can result in broader political backlash, which defeats the original aim of the litigants. For example, litigation might require climate mitigation that leads to the adoption of geoengineering technologies or the displacement of communities for the construction of wind or solar farms. Civil society actors themselves may become subject to litigation intended to limit their ability to police environmental harms (termed ‘strategic litigation against public participation’ – SLAPP – suits) or suffer criticism from sectors of society that disagree with the adoption of environmental or climate protections.

These ambiguities illustrate that, as with all avenues to tackle climate change, litigation is nuanced and can have a variety of flow-on effects. However, the rise in strategic and routine cases, a ramp-up in legal action by NGOs, the expansion of climate change suits into other areas of law, and improvements in climate science suggest that the use of climate change litigation as a tool to effect policy change is likely to continue. It is therefore important that climate change litigants carefully consider which new cases to bring, how to bring them, and assess the potential impacts of litigation within the wider context of efforts to enhance climate change mitigation and adaptation action globally (report p. 10).

As Joana Setzer, research fellow at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science and co-author of the report, concluded in a press release:

“Litigation is clearly an important part of the armoury for those seeking to tackle climate change. Court cases contribute to greater awareness of climate change issues and can force changes in behaviour that could reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It remains an expensive and potentially risky option, though, if compared to other routes like policy-making.”

Alas, the Trump administration eschews adopting any policy to address climate change, so litigation – this “expensive and potentially risky option” – continues to loom large.

When will someone will bring a suit against college sports teams flying distances to play games? I’ve wondered just how many air miles professional and college sports teams fly and I found this paged this morning. It is for the top 40 college football teams for 2018.

The link is long so I used tinyurl: http://tinyurl.com/yya54ktk

Copied the data into a spreadsheet and the total is 250,688 for that selected set. Would add up to a lot for all sports teams, but would probably be dwarfed by what the military does.

The US Military is the single largest user of hydrocarbons on the planet.

Thanks, Jerri-Lynn for this overview of the state of climate change litigation.

I think it’s encouraging that more people in more countries are starting to bring suit to support action to mitigate climate change or maintain existing regulations. This is an all-hands-on-deck situation and regardless of the expense and slow pace of litigation, any useful strategy is welcome.

What do people suppose will be the net effect of this? The most likely scenario I see are energy companies closing shop in the first world and moving it to the third. So we lose high paying jobs at facilities here, that operate under the tightest regulation (whether you think it is enough is a separate debate), and move those operations to what, Mexico? Indonesia? China? The energy and materials WILL be produced somewhere. I’d rather it be produced in a country with the best regulation vs the worst, especially if my community can benefit from high paying jobs.

Certainly this dynamic must inform the debate somehow? Otherwise I just see special interests suing other special interests to get changes they can’t get politically, and in the process set our civilization back 200 years.

the best regulation is to stop using fossil fuels, one way or another. if all the fossil fuels are going to be used, we are in deep, deep, trouble, and the loss of some high paying jobs will be the least of our troubles. keep it in the ground.

And how do you propose getting Asia on board with that?

You do understand fuels are only one of the outputs from hydrocarbons. Plastics seem important to you?

china is already doing more. and you are dodging the point, it needs to stay in the ground. we don’t somehow win by winning a race to the bottom of the cliff. that’s not an argument.

I guess by “dodging” you mean directly addressing your idea that we can simply stop producing hydrocarbons. I’m looking for a real answer to a legitimate question, you are the one supplying only rhetoric – “race to the bottom of a cliff”.

China is surely pushing green energy. I won’t argue that. But do you think ANY of their regulations regarding emissions, waste, etc., are better than the US?

No! The US is Best, on Every Count!

More rhetoric. You’re giving NC commentary a bad name.

Certain kinds of things are less fungible than others. Electricity for example. Producing power in Mexico and transmitting it to the US as an end-around on US regulation would be costly in infrastructure as well as lost power (higher emissions per MWh). However, if we in the US decide to price emissions into products like electricity, gasoline, meat, etc then perhaps we will see a race-to-the-bottom kind of arbitrage of environmental laws. Solutions? I don’t know. But we have to start pricing in the costs of these things (such as CO2) in order to push consumption and behaviors and investments into productive areas. See: https://medium.com/@jonathan.engel/paying-the-true-costs-of-living-78946ee0e9f2

This question is very real under the current Corporate Global Plantation World Order and its Forcey-Free-Trade economic regime. And under Forcey-Free-Trade, there is no answer. Because if the US unilaterally reduces the involvement of fossil carbon in its energy economy, the US market will be carbon-dumped into by carbon intensive production from America’s many Trading Enemies.

If America could unilaterally withdraw entirely from the Forcey-Free-Trade world order, America could then institute whatever carbon controls it likes within its own borders. America could then ban imports from countries which have carbon controls which are the least bit looser.

But we can’t do that now, under Forcey-Free-Trade occupation. And as long as America is part of the Forcey-Free-Trade Corporate Globalonial Plantation World Order, your question has no answer.

Today:

https://www.ft.com/content/2c7b8438-a5a6-11e9-984c-fac8325aaa04

ESG money market funds grow 15% in first half of 2019: Big asset managers are launching more socially responsible options to meet investor demand

The article does not include any metrics about how much of this is driven by lawsuits, but it’s an interesting question.

And mid-June 2019: https://www.ft.com/video/cbf461ed-24f7-4e5a-a8fc-adf1f06d0ccf

Financial Times launches ‘Moral Money’ about ESG investing. Finally.

Meanwhile, the DNC has completely and appallingly dropped the ball on what could genuinely set it apart from the GOP — a debate focused *solely* and entirely on Climate Change. Mitch McConnell himself could not be more 1990.

Currently, the capital markets appear to be making more strategic decisions than either legacy US political party.

The political questions surely link up with judgeships: it is entirely possible that the Trump admin and its supporters are not all that worried about climate lawsuits, because they have been stacking the courts with neoliberal judges. If that is the case, then US political legitimacy will take yet another huge hit.

I’m not sure how it works elsewhere, but there isn’t a good track record for suing the stupid out of people where i live.

Australia has the dubious honor of being top of the table. Why is this I wonder?