Yves here. I don’t mean to be a nay-sayer, but having developed major orthopedic problems after an accident, I find it hard to be cheery about getting old. This article makes a passing mention of financial stress among the elderly. A new story in the Financial Times, adding to a 2018 study Greying of US Bankruptcy, chronicles the rising level of indebtedness. Key sections:

In 1991, over-65s made up only 2 per cent of bankruptcy filers, but by 2016 that had risen to more than 12 per cent, says Robert Lawless, one of the authors of the report and a professor at University of Illinois College of Law. (As about 800,000 households filed for bankruptcy that year, this works out as approximately 98,000 families or about 133,000 seniors, since many file jointly as couples, he adds.) Over the same period, elders grew as a percentage of the US adult population too, but only from 17 per cent to 19.3 per cent….

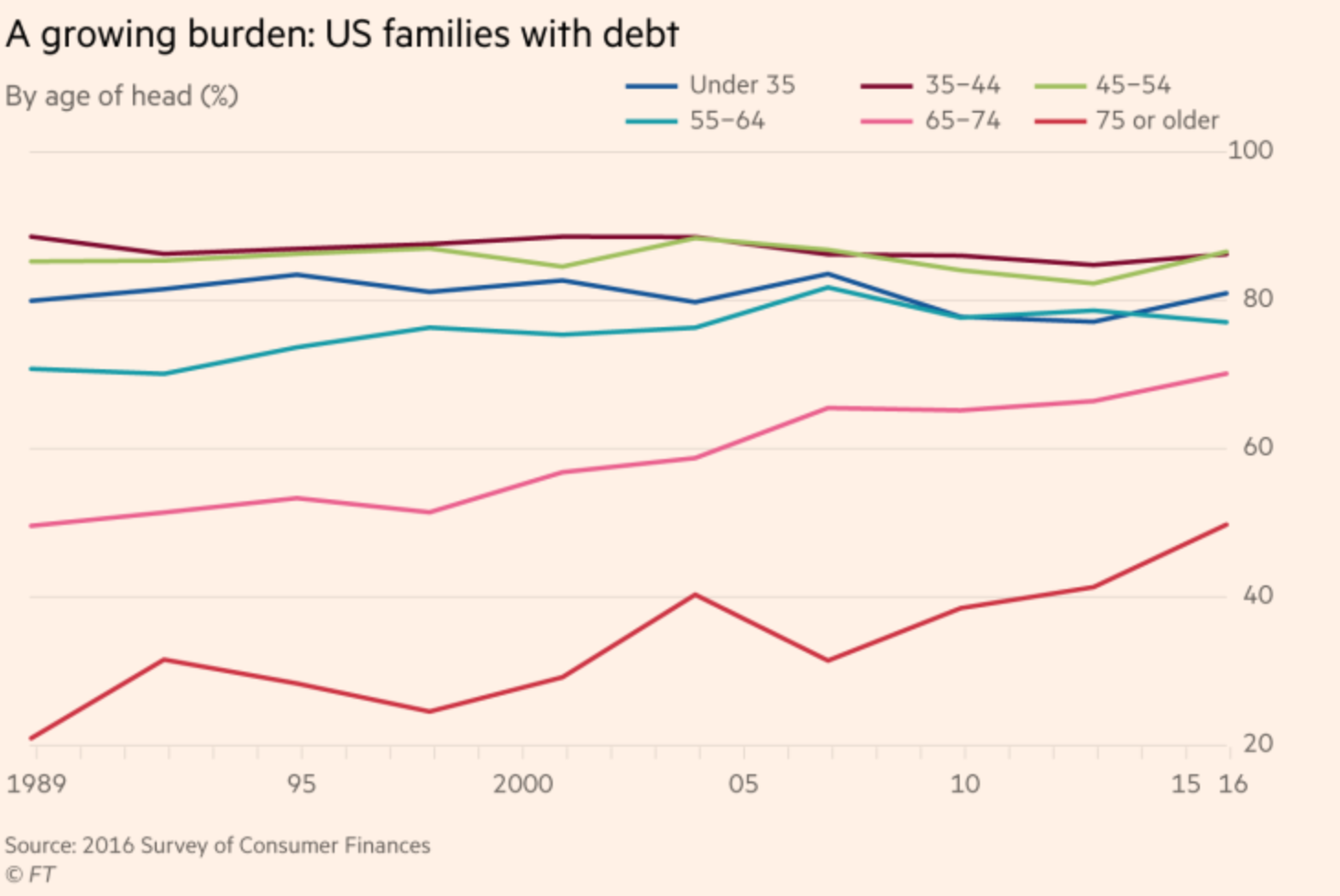

In 1989, only one in five Americans aged 75 or older were in debt; by 2016, almost half were, according to the most recent US Federal Reserve survey of consumer finances. The rise in senior debt comes at a time when the wealth gap between rich and middle-class or poor Americans is at an all-time high, according to a study last year by the Pew Research Center.

By 2016, the wealth of upper-income Americans had more than recovered from the post-2008 recession, but the wealth of lower- and middle-income families was at 1989 levels, highlighting the long-term rise in income inequality in the US.

As these low- to middle-income families age, many are being pitched into debt-burdened retirement by several structural trends, including the decline of trade unions, with their power to negotiate real wage increases, good pensions and retiree healthcare packages; the disappearance of defined benefit pension schemes; steep healthcare inflation; and a sharp rise in middle-class families helping to pay for children to go to college.

By Valerie Schloredt, the the books editor for YES! Originally published at Yes!; cross-posted from openDemocracy

So I’ll be out in public, maybe ordering coffee, and someone I don’t know will address me as “sweetie.” I’m a 60-year-old woman, and I look my age. Because people haven’t called me “sweetie” since I was about 5, I’m thinking this is an age thing. That seems more obvious when a stranger ironically addresses me as “young lady” in situations where “excuse me,” “hello,” “hey, you,” or “pardon me, ma’am” would do just fine.

Such micro-aggressions, conscious or not, don’t just target older women. A friend my age who sports a distinguished gray beard was sweating through the last stretch of a half-marathon when a young guy in the crowd yelled from the sidelines, “Way to go, old dude!”

For decades, ageism has been one of the “isms,” along with racism, sexism, and ableism, that are unacceptable in progressive discourse and illegal under U.S. anti-discrimination law – at least in theory. Yet ageism against older people remains the most unexamined and commonly accepted of all our biases.

Look at media, from advertising to news, that portray aging almost exclusively in terms of loss – of physical and mental abilities, rewarding work, money, romance, and dignity. That sad and often denigrating picture leads us to fear aging. To distance ourselves from our anxiety, we label older people, regard them as “the other,” and marginalize them, perhaps most obviously in casual, patronizing remarks to strangers.

I’m seeing ageism a lot more clearly now that I am subject to it. So I welcomed Ashton Applewhite’s encouraging new book, This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism. Applewhite, who has been speaking and blogging on the subject for several years, takes a particularly empowering approach by discussing ageism from the perspectives of both the personal and the political, debunking myths along the way. Take the “deficit model” of aging – the common assumption that getting older is all loss and no gain. In reality, we humans retain all sorts of qualities and abilities as we age.

We’re also adaptable. That’s a quality that can have unexpected benefits, like the “U-curve of happiness” described in a paper published by the National Bureau for Economic Research. The authors found that older people report being happier than do people in middle age. We deal with declines, of course, but we may actually get better at some things, like discarding superficial values, solving emotional problems, and appreciating life’s pleasures.

That bonus in emotional resilience may come in handy, because we’re aging in an economically, politically, and socially volatile era. According to Applewhite, poverty rates for Americans older than 65 are increasing and 50% of the baby boom generation feel they have not saved enough to create sufficient income should they live into their 80s and 90s. And while employment discrimination against older people (40 and up) is well known but difficult to prove, half of the boomer generation doesn’t see how they will be able to retire at all, Applewhite reports.

In her new book, Downhill from Here: Retirement Insecurity in the Age of Inequality, Katherine S. Newman looks at the current economic landscape for older Americans and concludes, “Retirement insecurity is an increasingly serious manifestation of the vast inequality that is eating away at the social fabric of America.” What is now a bad situation for many boomers could be even worse for Gen Xers and millennials when their turns come.

So here we are, becoming more vulnerable over the years in a system that already treats people as expendable. Applewhite, for all her good-humored tone, calls out that system as global capitalism, as when she critiques the intergenerational competition narrative. The image evoked is of greedy oldsters sucking up jobs and houses and Social Security and Medicare, leaving nothing for the next generation.

It’s easy to be pulled into the generation blame game, abetted by underlying ageism, and to forget that economic systems are not inexorable phenomena like gravity or time; rather, they are the result of choices. In fact, rather than regard older people as leeches, we should remember that economic interdependence is intergenerational. Older people are an intrinsic part of society. Most of them have supported younger and older people in whatever ways were available. And whether working or retired, they buy products and services and pay taxes and contribute labor, support, and finances to their families and communities.

Applewhite caps her manifesto with recommendations that strike me as parts of what could be a Great New Deal for Age. It could start with more flexibility in employment so people could have longer careers, with more time out for training, exploration, and family. Resources would be put into accessible design for public spaces, as well as programs to support mobility for people across the spectrum of age and ability. That would facilitate their inclusion in community, and they would be in good shape to take part because of improvements in health policy, clinical practice, funding, and research. And if, toward the end of life, more intensive care were needed, workers and family members doing paid and unpaid care work would be fairly compensated or supported.

The truth is that improving systems to include older people would improve access and prosperity and quality of life for everyone.

All that calls for a new movement against age discrimination and organizing to get socially responsible representatives and policymakers into office. It also requires the sort of consciousness-raising and agitation that is now going on around the issues of race, justice, climate, and gender. Waking up to the real harms of ageism and refusing to feed the beast with our words and actions is the first step. The good news? The job is open to anyone and everyone, regardless of age.

Yves,

Practice Somatics as taught by Thomas Hanna and Martha Peterson. Amazingly powerful at overcoming Sensory Motor Amnesia SMA. I had significant results in my 1st class. An easy enjoyable read by Martha is “Move Without Pain.” She learned from Hanna and took the concepts a bit further. https://www.amazon.com/Move-Without-Pain-Martha-Peterson/dp/1402774591/ref=sr_1_3?keywords=moving+without+pain&qid=1565359782&s=gateway&sr=8-3

I know you mean well but I have severe mechanical restrictions in key joints now. This is not amenable to a movement therapy.

Hopefully the further from the stress and physical activity of moving you get, the better you will feel.

I had joint problems for years, got over it slowly. Diet changes worked for me, plus time. Once the cartilage is gone, it’s gone. However, the subtle inflammation around it can often be affected by choices of food in my experience.

I found keeping a diet diary of everything eaten helps. If I wake up stiff and sore, I look what was on the menu the night before and avoid it. Same for a great morning, repeat the good foods from the day before.

Writing it down is better than trying to remember. Patterns are easier to see. I discovered through a process of notation and avoidance that certain herbs caused arthritis like symptoms.

Wishing you a speedy recovery.

I am saying this as someone who has had to live with health problems since I was 16; Healthy ageing is not about sadness or joy, it is about acceptance. This radical acceptance does nothing for the pain, but greatly reduces our suffering.

Capitalism does not want you to accept things as they are, it wants you always to be looking for better. They will cure your pain but will never touch your suffering. Pain is a fact; suffering is emotional.

We should still try and cure what ails us physically, but when we are not suffering, we do not fall pray to rent extractors and scammers. And as a consequence, we also end up not walking all over other people to end our suffering.

This is the core of the major religions and it is where authentic love arises.

+100

Very much agree with everything you said.

Radical acceptance, wonderful phrase!

I call it adaptation.

While ageing, I’ve learned to adapt my workout routine (physical fitness). To lessen the impact on my ankles, knees and hips, I now swim and cycle more. To maintain cognitive ability I read NC (and thank you commentariat); no TV for me. To help the next generation I drive less and try to maintain a small carbon footprint (no flying, no red meat). The most important advantage of ageing is being wiser (if you choose to be).

Yes – ‘Pain plus acceptance equals pain.

Pain plus non-acceptance equals suffering.’

“This radical acceptance does nothing for the pain, but greatly reduces our suffering”

Exactly this, I have knee problems which have been with me since I was a teenager…as I aged it got much worse. I have finally learned to accept that this is me now, yes I have to go slower,take the elevator,wear my knee braces and sometimes just stay home.

I finally figured out that I can’t fight it and I do find I am getting used to the pain and it doesn’t seem so bad.

100%

As someone who suffers from scoliosis. The back pain stopped affecting my life the day I realized it’s what I must live with and stopped taking the codeine and muscle relaxants I was prescribed. I instead focused on learning Pilates and through that I’ve been able to manage my pain to the point where I have no pain, unless I sleep badly.

Also another thing depression taught me. I got depressed following my move to Lagos after my MPP. I got depressed just by understanding the limited life (read financial) choices I had as a young Nigerian hoping to live and work in Lagos. At that time, everyone encouraged me to move back to London (I’m also British) that I’d get a job anywhere. But I felt that was running away, I’d move to Lagos because I wanted to be part of those developing Africa (in Africa) I just wasn’t expecting to find 23% unemployment levels and no chance of loans from banks. I took that shock and pain and decided to start a business that not only takes care of me financially and intellectually (because I am being creative) but allows me to work in my passion (African development) and still give something back to my country (I currently employ 3 people).

I feel maybe humans are like plants, we need both rain (bad times) and sunshine (good times) to REALLY grow into our FULLEST potential.

My parents worked hard, saved a decent amount of money, did the stuff you’re supposed to do. As he aged into his 70s, my dad’s health deteriorated to the point where my mom couldn’t take care of him at home, so he went to a long-term care facility. After a couple years of that, my mom had to start considering whether to divorce him in order to not be put in the situation described above.

‘Fortunately’ he died and my mom didn’t have to make that decision. ‘Fortunately’.

Our country is inhumane.

Yes, and it was not entirely accurate for the author to say that the elderly live in a system where people are expendable, since the elderly and their inevitable health issues are seen as a desirable revenue stream and profit center, at least until their resources have been exhausted…

It is like most things in the US, your wallet and bank account are desired until they are empty. I feel as if I am surrounded by vultures, and I could become the carcass through bad luck, or just by living.

Life reduced to a series of amygdala exploits and Black-Scholes applications, where companies develop ways to prey upon and extract every last cent even beyond the grave. Their motto seems to be Nice life there, shame if something happened to it.

I feel exactly the same way. Most business models are based on providing the least possible while pricing is outrageous. You have to spend hours on the phone to get anything resolved across a number of different businesses.

It is perhaps ironic that JAMA online just came out with a paper (Al Rabadi, LeBlanc, Busy, et alia) on age and assisted end of life (which they coined “medical aid in dying (MAID).” It was pretty much a data dump from Washington and Oregon. An accompanying commentary by Daniel Sulmasy, complains that the Al Rabadi, et al. study does little to inform medical ethics of what Sulmasy preferred to label in “sin terms” as physician-assisted suicide. Therein lies the rub. Many patients and their physicians cannot get beyond notions that only God has the right to terminate life. So, most states require many terminal patients to drain their spouse’s legacy in the name of medical ethics.

What can you say about getting old. It sucks, but it is better than the alternative. When I was younger I heard the old phrase that ‘youth is wasted on the young’ and I can sympathize with that viewpoint. As far as capitalism goes, you are only worth your economic value to the system and no more. ‘Homo economicus’ here we are. But here is the thing. If you were able to maintain your health clear on to the end it would not be so bad but in reality, as you grow older, your body starts to break down. Problems rack up and then you get hit with something major and that makes you vulnerable.And it is at that point that you become vulnerable to being exploited by a capitalistic system. This system seeks to make a ‘killing’ when people are vulnerable. It is what it does. It is all it knows how to do.

Myself? I am going to try living forever – or die trying.

The best exercise for the elderly is weightlifting. Unfortunately, this is not widely known and is not encouraged. I am the only older person at the gym in The Netherlands and in Canada lifting weights.

I’m an oddity.

But my body is strong.

Yes- works for me too, plus I can pull myself out of depression with the

lifting. Not always, but often.

Yves, has mentioned this topic. I believe she attends a gym to do just that. It is why most people should walk up stairs, it is bodyweight lifting (it stresses your quad muscles in ways walking on flats does not). Lifting weights in a gym (after appropriate instruction) is relatively safe using machines (stay away from the bench press, unless you’re lifting modest lbs. at high repetition (15-20)). While body balance (positional orientation) decreases rapidly after age 50 (or so), muscle tone/strength can mitigate injury in a fall. There are also body metabolism processes that improve with greater overall muscle mass.

I use a commercial-grade step device called the X-cisor. While it’s not cheap, the moving parts are hydraulic, it’s made of aviation-grade cast aluminum, has various resistance settings, and fits under a chair. I expect it to last for my lifetime, given that I place demands on it well below its tolerances.It improves balance, is easy on the knees and hips, and can even be used for upper body strength exercises. I hate going to gyms, and this neat and beautifully-designed little baby allows me to stay fit without having to.

after i finally got my hip, i found that the rest of me had deteriorated…35 years prior to hip crash of hard living, hard playing, hard work, and compensation for dead hip, etc

so i lingered around for a year, fretting over my early onset dotage.

but then i found a 4 foot rattler in my library: we needed a new house.

so i built one, this monument to stubbornness,as physical therapy/art project.

took me almost 4 years…wife and boys helping on weekends…but mostly just crippled old me.(no mortgage. “financed” with EITC, plus all the material my family habitually hangs on to)

I’m still broken…always will be. the guy who replaced my hip, looking at xrays of most of me, said i have the skeleton of a 75 year old(i’m 50 in 3 weeks). But I’m a lot stronger than i was right after the hip replacement…physically and otherwise.

so yeah…”weight lifting”…in my case, with a purpose.

Yves…like i tell my wife…remember that you are mighty.

i call it “bruxist tenacity”.

i’m with you in rockland.

Can you post a link or more information on this?

So the author’s big complaint is that someone called her “Sweetie” or called some Old Dude “old dude”? WTF? These “issues” are what my son calls “White People’s Problems” because anyone else is worried about the real problems of exponential healthcare costs, social isolation, trying to live independently in a dignified manner and making a social security check last through a five week month. And – I hate to tell you this – I wouldn’t trade my age (yes, I am in my “golden years”) to be 30 for all the money in the world. At least we have some social security and Medicare to tide us over. After these guys get done I doubt anyone under 40 will ever see either of them.

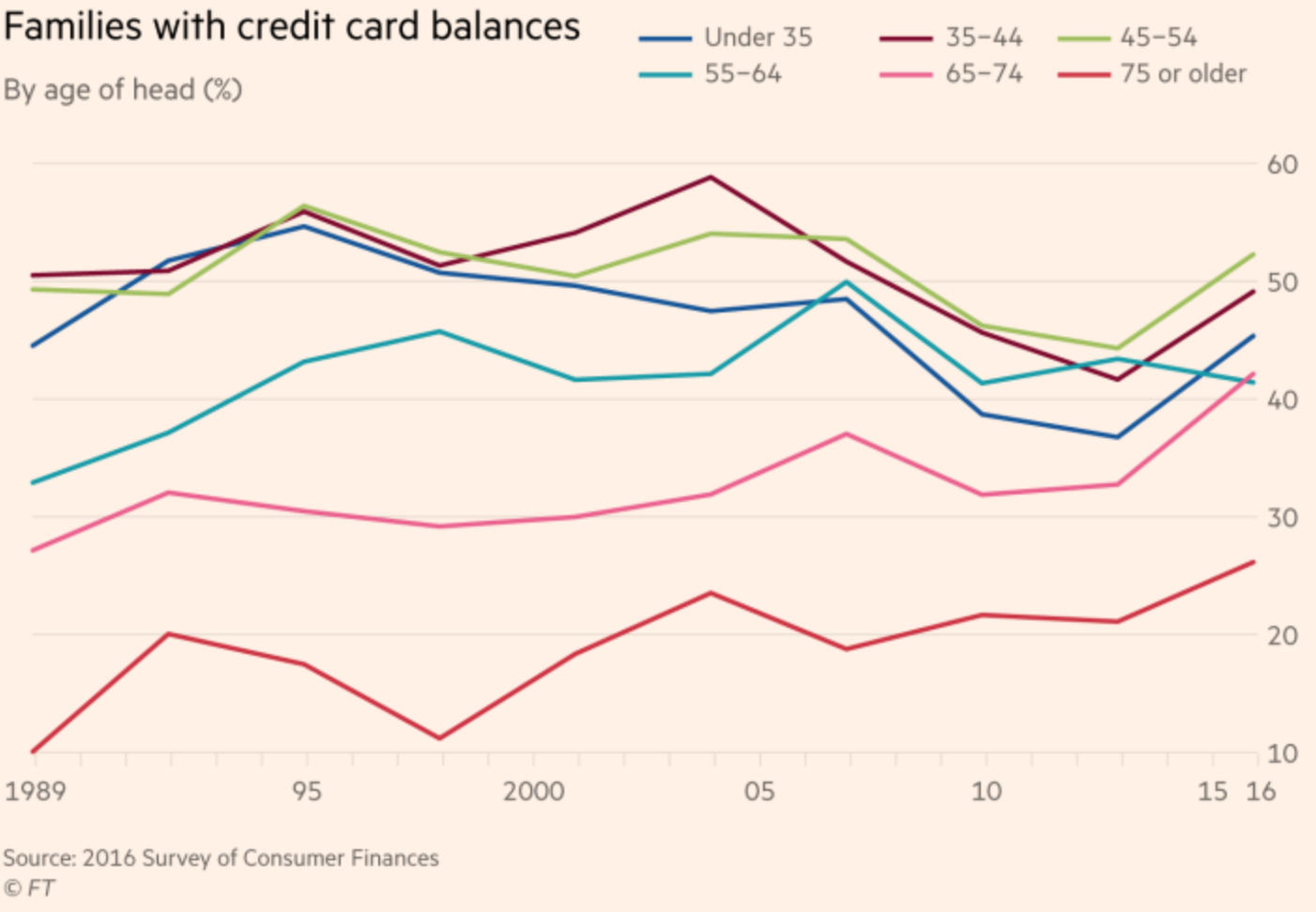

We don’t need “Great New Deal for Age.” (Once again, we get subdivided by categories so that one group is “getting something at someone else’s expense”. It’s a sure political fail.) Let’s get healthcare for all people from cradle to grave. (How much you wanna bet that those seniors who are carrying credit card debt are doing so because of dental bills or chemo treatments or some other healthcare expense?)

Stop whining. Start fighting.

I think capitalism and fear of aging is perfectly rational. I fear age discrimination in employment, fear it to no end, agonize over any career choice that isn’t maximized around the question of: where is this going to get me by 50. Because if you aren’t somewhere EXTREMELY solid and stable job wise by then, you are done for. That’s all she wrote.

I fear if one ends up unemployed in their 50s or older, in many cases they will never work again. Only reoccurring unemployment is a constant at all ages of life from my experience. And few, and not me, have enough to retire by 50.

Very true. I happened to foresee this, and became a public school teacher at forty in order to have a union job with tenure, seniority protections and a defined-benefit pension (which, needless to say, neoliberal privatizers are attacking).

Even if you earn a decent income, you have make it through your fifties without getting whacked. A good friend of mine who worked in publishing for thirty years, got fired at fifty-two, and is now homeless, having exhausted his IRA. True, he made some very foolish financial decisions along the way, but much of savings was eaten up by health insurance costs. No one should have to face that after decades of hard work.

“Old age is not a battle; it’s a massacre” — Phillip Roth

“Old age is a shipwreck” — Charles de Gaulle

Shorter: “How Capitalism exploits Everything”

My commentary: how can an “-ism” do anything? Does an “-ism” have a brain and a mind of its own? Isn’t Capitalism made up of people, who make decisions that direct their organizations to behave in a certain way? What do these outcomes say about these people?

Bonus: These are the same people who try to lecture us about personal responsibility, while doing everything possible to hide behind the Corporate Veil. My belief is that the Corporate Veil should not exist.

@Krystyn Walentka

August 9, 2019 at 10:27 am

——-

This was meant as a reply to Krystyn, above.

+100.

“Radical acceptance” is, to me, an important concept for enjoying old age. While I don’t have the kind of difficulties that you have mentioned in previous comments, I am experiencing some of the common health issues of my age (69) such as the beginning of coronary artery disease, prostate issues, and others.

I made a decision 50 years ago that I am what I am and whatever that means, I will accept that as the path that my life is taking. That doesn’t mean just letting things happen to me; I have the ability to change the path somewhat to meet my needs in most cases. However, it does mean accepting those things that I can’t change.

That radical acceptance has enabled me to be content with my situation and avoid the anxiety about aging that our culture tries to impose on us. (To me, contentment is more important than happiness, which is not sustainable as an emotional state.)

Acceptance comes in various forms and at different times. Just as younger people grow into adulthood and then may start perceiving others as fellow adults and then fellow humans, so do aging people transition into accepting who they are and how they have lived, at least that is the theory. Some practice that more than others and the hope for all is to have greater awareness that such introspection may lead to greater communion with one’s fellow humans. Life doesn’t have to be nasty, brutish and short, or as much depending on circumstances, with some awareness of self and environment. It isn’t just be born, deconstruct life and then die as there is plenty of room to live.

“Old age is the most unexpected of all things that happen to a man,” Trotsky is supposed to have said. No truer words, at least not in my experience.

This article by Barbara Ehrenreich seemed pretty sensible to me:

But “health” is at best relative, especially so in age. And we fear the weakness and dependency that age imposes on us. So we assent to “treatments” to forestall or ameliorate those effects a bit. Waving away the knowledge that medicine has developed into something none of us can afford: expensive in all weathers and exponentially more so the closer we get to the end. But here we are.

Ehrenreich is brilliant and the linked article is so rational that one might miss that it is equally profound. Most importantly, she is responding to her life, not the described life which we are all told to expect, and surely she is fortunate to be in good health for her age. Not everyone is so fortunate. But knowing that so many face major obstacles through aging should not encourage those whose obstacles are less cumbersome to go looking for ones that are. Stress reduction is one of the healthiest goals for anyone at any age but especially for us oldsters. Too many doctors stresses me more than too many donuts!

Ehrenreich is so perceptive. I’m always plugging her book “Brightsided” denouncing the creepy cultural fiat of positive thinking. Funny, my mother “didn’t inhale” and lived to 87 but she had COPD so probs would have felt better without the puffing.

Another brilliant woman’s remarks on aging: “Whatever happens, I will get through it somehow, so why fuss? It’s not surprising that old people easily glide into a general gloom given how much we lose in our later years, but pessimism is very boring and it makes dreary last years even drearier. And one should never expect young people to want the company of old people, nor make the claims on them that one makes with friends of the same age: “Enjoy whatever they are generous enough to offer, and leave it at that”. (Diana Athill)

I have decided to follow the Roman example when I get inform.

All I need is the sword, or equivalent.

I like how Petronius Arbiter handled it. When he got the “suicide order” from Nero, he arranged a party for all his old friends and exsanguinated slowly during the meal and conversation. Stoic to the end.

Rumour has it the Terry Pratchett did similarly.

Alas, this can be twisted to become a ‘tool’ of the status quo. My go to example is a Nazi era film about just such a situation. The film was made to prepare the citizenry for what was to come. The ‘Manufacture of Consent’ in it’s most pernicious form.

The film: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ich_klage_an

The Nazis had a concept they called “a life not worth living” they employed psychiatrists to examine and certify people, many of them institutionalized children, who would then be euthanized because they fit the description. The psychiatrists filled out a small index card sized form and were paid a fee for each certificate.

I read about their work in a book; Psychiatrists-The Men Behind Hitler :Architects of Horror.

The torture implemented by the CIA is guided by Psychiatrists. (Looking at you, Gina.)

A non-solution. We strive to understand the process of life and aging. But it still eludes us. Every lifeformis a treasure trove of information. What we do with it is political.

It should be political, but today, most things capable of being exploited have become economic. Now, if we can reassert the primacy of politics over economics, especially finance, we will be more than half way to restoring balance to living.

Three score years and ten.

Some make it. Some don’t.

After that one is either a burden, or a potential burden.

It’s not the sudden end which is painful

but the lingering end, coupled with the rent extraction.

The 70 and 80 year olds heading our political system really appear as serious obstacles to pressing issues, probably because of their life-long entangling personal alliances.

The Nazis may have believed in that “Ich klage an” ideal but it was not practiced across the board. One writer who lived through the war mentioned in one of his novels that, if in a air raid you saw people fully enveloped and being burnt to death with no hope of helping them, that if you shot them to put them out of their pain that you could be charged under the laws as being guilty of murder.

There was an echo of this in the Katrina storm when old people who had been abandoned by the state were put down by medical staff which had all sorts of ramifications-

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/30/magazine/30doctors.html

The Katrina Experience is a prefiguration of the neo-liberal future. We were there. It did not work out well for most people.

To refer to what happened in New Orleans in 2005 as “the Katrina storm” is to buy a narrative created by editors and producers when the hurricane first made landfall in Mississippi, where it wreaked massive wind damage (houses flattened, e.g.). In New Orleans, which the storm missed, the damage looked different (houses moved three blocks off their foundations) because the cause was different. For the curious, check out “The Big Uneasy”, a doc about the twin parallel investigations of the disaster. https://vimeo.com/137159734

yep a quick end as opposed to being a profit center for various leeches.

This was the philosophy of someone near and dear to me, a physician.

He made good on this philosophy when he decided his race was run.

The Buddhists have this pretty well figured out.

http://www.mirrorofdharma.org/2012/10/the-four-eight-sufferings.html?m=1

Radical acceptance of these truths will spare a lot of suffering.

Meanwhile, rage against the machine of neoliberal monetizing of suffering and dying.

Crush neoliberal capitalism.

Getting old is not for sissies.

“I hope I die before I get old”

As that old song, “My Generation”, by the Who goes. (I still have that on a vinyl record in surprisingly good condition)

This boomer still holds to that credo. It’s just that the goalposts for my definition of “old” keep moving;)

never trust anybody over 90.

So far all my boomer aunts and uncles have died of cancer or diabetes before reaching SS age. I bet a few will make it, though… there’s quite a few of them.

> It’s easy to be pulled into the generation blame game, abetted by underlying ageism, and to forget that economic systems are not inexorable phenomena like gravity or time; rather, they are the result of choices.

Sure. I agree we shouldn’t subdivide people by generation — what matters is class.

But if old people sabotage M4A because they fall for insurance co propaganda — who exactly will bother to defend their SS and Medicare when the austerians come for it? If you look at the numbers, the Boomer+ cohort are the ones who are going to defeat universal healthcare.

My parents have a comfortable union retirement with health care benefits. Go figure they oppose M4A. Can’t even mention it without being called a communist.

I wish you had said some old people as well as many middle-aged and young people instead.

As an “old person” I fully support M4A even though, at 66 years “old”, I’m still working full-time with many, many professional class middle-aged and young people, 25 to 55 years of age, who are 100% against “socialism”, i.e., M4A, and they make no bones about it.

It is a class issue, period.

What is sad about that phenomenon is that the “middle class” people who rail against the forces of ‘Evil Socialism’ are usually the ones who are staring a loss of status in the face. Sort of like whistling past the graveyard.

That precariat still thinks in terms of a ‘Social Contract.’ Alas for them, the Elites tore up that contract forty years ago.

But that is one of the forms of discrimination: making broad generalizations across a group of people.

The older you are, the more likely you are to be conservative, statistically speaking (there are no generational cutoffs, just straight lines). But Bernie Sanders is 76 and there are teenage extremist Youtubers.

Also, agreed, the younger you are, all else being equal, the worse off you are right now. My entire life has been filled with a lot more financial stress, starting from childhood, than a similar American who was born 30 years before me. It has been painful trying to discuss career choices with parents (why don’t you become a university professor? ha! ha! ha! why didn’t you become an astronaut?). But all else isn’t always equal and we should be accepting allies where we can get them. And even the 30-years-older version of me was still getting exploited by capital so let’s just make common cause.

I’ve always had a “baby face” and I’ve gotten the other version of age discrimination, including especially from gray-haired individuals who (I can’t blame them) wouldn’t want to be called “sweetie.” I remember a workshop where another participant was a 70-something gentleman who got quite upset that I called him “sir” but wanted to lord over ever discussion like a Nobel Laureate leading a symposium.

Can we just have a single, universal, standard, that we judge actions rather than people and just should never make assumptions about people? Also, if you are peers in a particular situation, treat each other like peers regardless of age.

When I moved to Oregon in 2001, I weighed about 230#. I am now 64 years old and as of two days ago, I weigh 136# which, along with my style in clothing, makes me look like the guy on the cover of Jethro Tull’s “Aqualung”, a great album from a great band. I have more important things to worry about than people discriminating against me. If I can’t arrest the weight loss somehow and regain stability, I won’t be commenting on blogs much longer.

Millenials and Gen-exers are having a lot more economic difficulty than my Boomer brethren had. What I am seeing is many Boomers continuing to help their kids and grandkids economically and in some cases endangering their own economic well-being. The idea that Boomers are all a bunch of geezer-greed-bags must be put to rest. Most of my geezer friends are caring, helpful and generous. Just sayin’.

So the conflict as I see it on the surface is that an aging population can no longer muscle around the big mechanisms of a steel forge; or do other labor intensive things. This is the definition capitalism gives to “aging”. But it is no longer the world of industrial capitalism. And there is plenty of value in the wisdom of older people. And if we have any faith in epigenetics we will nurture the elderly just like we nurture the young. They will all contribute to our progress.

Thanks for the post and the many informative comments.

As all of us are at all times ageing since the day we were born, and as not a few of us approach 60, 70 or 80, the problems mentioned here will likely show up in our lives, or maybe not (or not so soon) if we are more fortunate.

Given the planet is also warming up (what a double whammy) at the same time, how will that impact what we should do? WiIl it be that what we do to address the problmes mentioned here will not matter, because the planet itself has only 10, 15, 20 or some other years to be our home?

A Day in the Life. Today we got 3 calls for age related cold calls. Medical services, medical devices, pretend Medicare information, etc. All very capitalistic/profiteer stuff. Feeding off the panic and helplessness of old people. Well, I’ve got news for them. I’m not helpless. And I never will be. I will avail myself of all the community services to be had. There are many. Every day I become more and more dissappointed and disgusted with “capitalism” which puts us all in this position to be blatantly exploited. Not just us passive seniors. It has wormed its way into the very heart of senior medicine. I even got a call from Bill’s doctor’s nurse saying the test results for an ultrasound for his abdominal aorta were inconclusive and they wanted to do a cat scan. So I said – well we didn’t even understand what the ultrasound was for, he has no symptoms. How much will a cat scan cost and will Medicare pay for it?? Well, she said, you can call them and find out. Well, I said, I can never get past their goddamned computer so will you please call them and if you can ensure us that this is in fact covered by Medicare then maybe we can schedule a cat scan. She almost hung up on me. She’s just one baby step above a cold calling scam artist.

Yes. I have had two of the ‘attending service providers’ from my bus accident experience send me duplicate bills, even though it is all in the hands of the bus company insurance company. Do I sense a double billing scam in play?

Susan the other:

I always appreciate and look forward to your comments, But I’d like to give you some advice.

In dealing with medical billing trap doors. it’s important to make sure the “providers” and the insurance company confirm that a scheduled procedure has “prior authorization”

This usually means the provider must first submit a written referral with correct ICD-10 and/or CPT codes and your insurance company issues a “prior auth.”

Here’s a primer: https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-are-cpt-codes-2614950

Incorrect medical coding is the main reason for unpaid medical, even when the procedure itself should be acovered.

A nurses assurance that a procedure is “covered” is worthless, and only means your plan lists it as a “covered service not that you have been authorized. Or she just wants to get to the next call.

Always talk directly to medical billing and coding/pre-auth staff, esp in large medical clinics or hospitals, small offices use your discretion, but insist on the pre-auth.

NOTE: Many insurance companies won’t issue the pre-auth UNTIL YOU HAVE SCHEDULED AN APPOINTMENT FIRST. Make the appointment, and don’t take the scan. whatever, until you get pre-authorization. Reschedule if needed.

As much a burden as this is, it gets easier with practice, calling and noting name, date and transaction number of your phone conversations can win your claim, especially when you can’t get copies of the prior auth. They always record these calls.

I won a case against CVS this way, but it required the intervention of the state insurance regulator (every state has one, mine let me file complaint completely online and took action), because CVS is run by criminals and has paid judgments for doing this to thousands of people.

You can also write on every financial responsibility form “consent is given only for in-network providers, pre-authorized services and refused for any out-of network, balance billing or non-covered services.” Whether a medical procedure is necessary or desirable is a different, and differently complex matter entirely.

But it can be done.

Cripes, Yes!

Did you mean, “The patient should always record the calls?” Whatever, record all your calls with authorization at the beginning from the person talked to, note on the tape, the date, time and the name of who you are talking to. Also, ask them to send you a verification of authorization by email, to an email address that you have created solely for medical and insurance purposes, that is, never give them your real email to avoid yet more spam.

Ask for everything to be sent in hard copy to your postal mailing address. I believe this triggers mail fraud statutes if they later claim they made a mistake and bill you.

Don’t forget to request and wait for and then take, at the time of the service, a copy of your X-ray, MRI or scan, on a disk. This has saved me a lot of grief when the “system is down” and doctor can’t see my images online.

Also, get hard copies of all lab results. I write

“Bill will only be paid AFTER hard copy of results are received by me,” on all the paperwork to authorize the service. It’s delicious when the collection agency calls and I can tell them to read their own paperwork. “Oh”, is usually the response.

“In 1989, only one in five Americans aged 75 or older were in debt; by 2016, almost half were,”. And that comes from a Federal Reserve chart, and that trajectory is steep.

That right there demonstrates exactly what Michael Hudson says, that “the tendency of debts to grow exponentially at rates in excess of the economy’s ability to create an economic surplus to pay creditors has been known for nearly 5,000 years.”

Ok, the “has been known for 5000 years bit” has been conveniently forgotten in recent times.

But if I was going to pick a statistic to back him up that one above is the one I would choose. And as he explains in his book And Forgive Them Their Debts, it leads to society failure/pitchforks. No doubt in my mind thats what we are seeing. The masses can feel what is happening, being slowly cooked like the proverbial frog in the saucepan but not understanding how or why, and so end up targeting lashing out at those who they think are the cause of their woes but who in fact are not.

Only took 30 years to go from one in five to one in two…

One hidden reason elderly are facing indebtedness is the decay of post-retirement benefits that were given as deferred compensation, but not secured by law. That is, ERISA wrote the guidelines for vesting in pensions, and although the PBGC is paying out way more than their actuaries calculated, pensions are far more reliable than health benefits. However, for the people who worked in the 60s and 70s, retiring in the 80s, it was commonplace to be promised lifetime health insurance in lieu of higher wages, under the bon mot “total compensation.” Some early retirements were incentivized with the promise, of post-retirement health care for life, in writing = contract. But, except for collectively bargained benefits, corporations are removing benefits or charging for the premiums.

So, where is the law in all this?

There are not enough skilled lawyers to take the side of retirees who may have contractually vested benefits that now cost thousands or have invalid high deductibles.

Legal action is available if certain technicalities are met, especially timeliness. Plans now include a time limit (unreasonable) to take legal action. Which wage earner has an ERISA lawyer on speed dial? Yet, courts uphold limits as short as one year. It can take a retiree that long to request pertinent documents and find counsel.

As well, where is the justice in all this?

Justice is a harder nut to crack for an average retiree. The corporate reaction to a lawsuit is a motion to dismiss. This is time-consuming and can eat up a budget while the plaintiff writes a defense of statute of limitations, eligibility, and technicalities while the merits drift farther and farther from the judge’s bench.

In the end, even if the plaintiff retiree is 100% correct in every action, most judges send the cases to mediation to keep the docket from clogging. Mediation is likely not about the merits. It is about power. Mediation ends in compromise. Picture a group of retired people who have endured a year or two of machinations about dismissal and the payout to counsel to send reminders or whatever that is not yet about the merits. The biggest asset for the retirees is what would happen if the case were public? Would that be enough to develop a performance-based resolution? Or is it more likely that mediation is a business tool to transition whole classes of elderly retirees to lesser plans? That would be cheap.

So, one more reason the elderly are in debt is that their planning factors that were good at the start are able to be chiseled away year after year and their legal clout is not great enough to preserve or restore them. Corporations once worked for a sustainable future. Recruiting and retaining good employees was an investment. In the late 90s and early 2000s, someone began the idea that employees were pure cost sinks.

Now, getting the one-year bottom line ready for bonuses is a dominant goal, and corporate raiders are invading the board room. Corporate raiders is the obsolete name for “activist investors.”

There is a distinct difference between old age of my mother’s generation and what’s going on now. Although she had a few different jobs when she was young and single, once she went back to work, having had her last child (me), she had one employer until her retirement. The company paid for her supplemental health insurance and between medicare and the supplemental insurance, she was well able to pay the small remaining costs of any treatment she needed. She didn’t die with much of an estate, but she didn’t die in debt either. One other difference of memory: no one called her a “Senior Citizen”.

I’m not sure of the interplay between the variously noxious, “cute” attitudes toward older people and their economic decline. I suspect it’s just the same kind of routine that they use to distract every age group from the corruption that is making our lives more expensive.

At 80, I have my aches and pains, but my recent bone density test says I have a mere 2% chance of a broken hip in the next ten years and a slightly less impressive 11% chance of some other bone injury in the same interval. That takes me to 90.

As far as the social aspect goes, call me an “old broad” if you want to, but I don’t answer to “Senior Citizen”.