Yves here. How a rise in immigration drives perceptions of risk.

By Vincenzo Bove, Professor of Politics and International Studies, University of Warwick,

Leandro Elia, Assistant Professor in Economics, Marche Polytechnic University and

Massimiliano Ferraresi, Research Economist, European Commission. Originally published at VoxEU

Between 2014 and 2017, more than 600,000 migrants crossed the Mediterranean and took up residence in Italy. Though crime rates during the same period continued to drop, a majority of Italians report feeling increasingly unsafe. This column investigates how immigration affects the perception of crime and the allocation of resources. Using detailed Italian government-spending figures along with municipal-level data on the population of foreign-born residents, it finds that immigration led to increased spending for police protection due not to higher crime rates but to the deterioration of social capital and unfounded fears of criminality.

The consequences of immigration are a salient and contentious issue in most destination countries, splitting public opinion and fuelling negative attitudes towards immigrants. Concerns about immigration often lead to tensions between locals and immigrants, religious prejudices or racist attitudes, and the emergence of extremist groups and support (Hainmueller and Hopkins 2014, Barone et al. 2016, Halla et al. 2017, Tabellini 2019). These tensions are frequently exploited by political parties to reap electoral gains. Anecdotal evidence suggests that immigration is associated with an increase in the fear of crime. A collective perception of insecurity can lead to the implementation of restrictive regulations and control mechanisms, including surveillance and profiling programs. It can also prompt additional public spending on security, even in the absence of any increase in the actual crime rate.

Against this background, our recent study (Bove et al. 2019) asked whether and how immigration affected public spending on police protection in Italian municipalities. The debate about law and order intensified after more than 600,000 would-be migrants travelled across the Mediterranean to Italian shores between 2014 and 2017. Since 2007, crime rates per 1,000 inhabitants have decreased by almost 25% across all Italian regions. Crimes perpetrated by foreign residents show a similar declining trend. Yet, by one estimate, 60% of Italians do not feel safe in their cities, making the Italian case a clear illustration of a broader point.

Study Design

Our empirical analysis is based on a rich data set. We combine detailed information on local government spending items for more than 7,000 Italian municipalities between 2003 and 2015 with municipal-level data on the population of foreign-born residents, from their country of origin to demographic and socio-economic characteristics. Our core variable of interest is security spending, which we compute as a share of total current expenditure, including police costs (such as salaries, police presence and patrols, and the capital component in the production function for law enforcement, from vehicles to communication devices and special clothing). We then leverage exogenous variations in immigration flows following recent rounds of enlargement of the European Union to construct a novel shift-share instrument. We complement this approach with historical data on migration and political preferences in the 1930s during the Fascist regime.

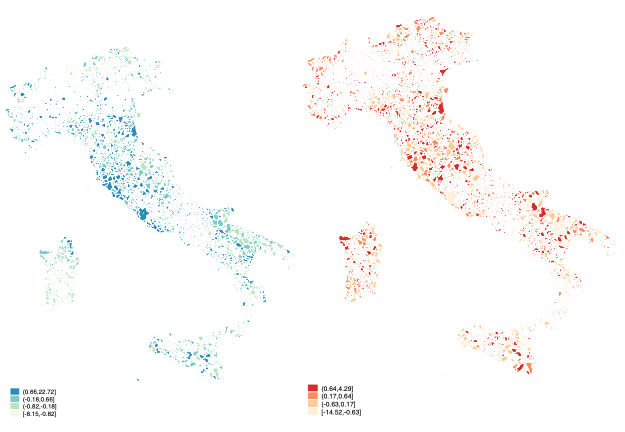

Figure 1 shows the distribution of public spending on security as a share of total spending and the share of immigrants across municipalities. These variables are residuals obtained from a linear regression after having controlled for municipality and fixed-year effects. Figure 1 indicates a positive security-spending-immigrant nexus, which is not concentrated but scattered across the country.

Figure 1 Spatial distribution of local spending on police protection and immigration

Note. The share of local public spending on security (left-hand map) and the share of immigrants (right-hand map) are residuals of a linear regression that controls for municipality and fixed-year effects using data over the period 2003-15.

Baseline Results

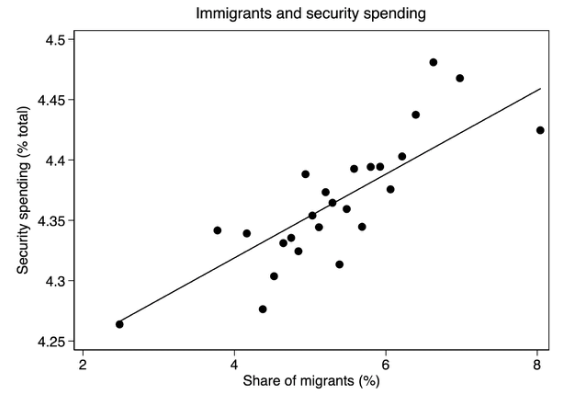

We find a positive and statistically significant relationship between immigration and local public spending on police protection (see Figure 2). On average, the amount of spending allocated to local security increases by 0.12-0.30 percentage points for every one point increase in the share of immigrants. This is a very large effect, as municipalities spend an average of 4.3% of their budget on security. We find that the relative increase in local security spending comes at the expense of the budget allocated to other important functions, such as culture, tourism, and local economic development. Italian cities have long struggled to afford the cost of basic infrastructure maintenance and to provide vital services. The estimated magnitude of this relationship is therefore not only statistically significant but economically meaningful.

Figure 2 Binned scatter plot of immigration and security spending

Note: Control variables include municipality and fixed-year effects, population density, share of 65+ population, average income, and a dummy variable indicating a domestic stability pact.

The cultural distance between social groups is likely to be a core driver of negative attitudes and prejudice towards immigrants as well as locals’ concerns about insecurity and national cohesion (Citrin et al. 1990). As a second step, we consider degrees of cultural similarity by including information on the genetic, religious, and linguistic proximity between immigrants and natives (Spolaore and Wacziarg 2016). We find that the cultural proximity of foreign-born inhabitants to the native population matters, and the relation between immigration and security spending is more pronounced as the cultural distance between migrants and natives increases.

Possible Transmission Channels

We offer three primary insights into the mechanisms behind these results. First, we ask whether municipalities with larger immigrant concentrations might be associated with higher crime rates, which could (eventually) motivate higher spending on municipal police. Our empirical analysis suggests that migrants are not significantly associated with higher crime rates. It also rules out the possibility that immigration, by increasing security spending, indirectly reduces crime. As such, the impact we observe on security spending is hard to square with a migration-crime nexus. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that immigrants are not more crime prone than their native-born counterparts; that they do not significantly increase the overall crime rate or the number of violent crimes; and that legalization further reduces immigrant crime rates (Bianchi et al. 2012, Bell et al. 2013, Mastrobuoni and Pinotti 2015, Pinotti 2017, Light and Miller 2018).

Second, we ask whether a misalignment between perceptions of crime and reality could develop at the local level, and whether immigration could increase the fear of future crimes as opposed to the actual probability of a crime being committed. Our individual-level data show that individuals whose neighbours are of a different race or birthplace are more likely to report that fighting crime is a national priority and to believe that immigrants increase crime-related problems.

Third, we ask why immigration shapes worry about crime and perceptions of feeling unsafe. A wealth of studies, mostly in criminology, suggest that trust and social cohesion in neighbourhoods are strongly associated with fear of crime (Brunton-Smith et al. 2014, Rader 2017). Higher demand for public order and safety at the local level could be driven by a deterioration in the degree of social capital – the ties and relationships that bind members of a society to one another. Social capital can be an indicator of a society’s cohesiveness and the extent of peaceful coexistence and individual interactions (Guiso et al. 2006). We find that immigration has a negative impact on the number of non-profit organizations, a common measure of the strength of social networks at the municipal level. Immigrants’ countries of origin seems crucial, and the coefficient is larger the higher the cultural distance between immigrants’ homes and their host countries. Having neighbours of a different race, or foreign neighbours, correlates negatively to trust in social interactions and erodes social cohesion and civic cooperation. At this point, we note that the erosion of social capital and the fear of crime provide a credible explanation for the observed pattern.

Implications

Immigrant populations in Europe have been growing rapidly for decades. Over the same period, crime has moved in the opposite direction, with the rate of violent crimes in many countries well below those of the 1990s. Yet, political parties in Hungary, Austria, and Italy have won elections using campaigns that whipped up fears about the impact of immigration on crime, and worries about violent crime have aided the political success of anti-immigration parties at the local level. This can have important consequences for a municipality’s determination of short- and long-term priorities and funding for local services. Understanding the consequences of immigration for the fiscal position of the municipalities they seek to join is crucial to developing effective public policy.

Authors’ note: The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication.

See original post for references

I have no idea whether the Italians have a gutter press which in the UK would highlight crimes by immigrants therefore raising fears among the natives or whether also as in the UK crime statistics have been fiddled by police. The latter appears to have resulted from New Labour targets & has also been reported in hospitals & public services – Adam Curtis covered the subject in his documentary ” The Trap “.

When I talk with relatives in England, they are in no doubt that the crime statistics are an exercise in fantasy – to what extent this is true I don’t know, but that is the perception as is that the Police go easy on immigrants due to the fear of being labelled as racist. I just wonder if there are similar elements apparent in Italy.

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/10460158/Police-officers-routinely-fiddle-crime-figures-MPs-are-told.html

Yes, a huge, and probably insurmountable problem with crime statistics is that police forces encourage reporting of crime — even minor, low level stuff that wouldn’t otherwise be of interest to the police and they’d actively discourage “unwarranted” police involvement — when they are angling for budget increases but then also discourage reporting of offences when some big cheese (such as the Police and Crime Commissioner or the Chief Constable) wants to show some initiative or other which they would like to claim credit for is “working”.

I’ve certainly seen this at work myself, an acquaintance in the next street was told to report the suspected theft of a home delivery package left in their porch (which might have been a localised theft crime, but might just as well be a courier or mail order company fraud/scam — the former being of potential interest to the local police force but the latter not really anything they’d be able to follow up) whereas a few years ago, a neighbour in a similar situation was told it wasn’t a police matter and to take it up with the selling company, the courier or trading standards (and told to make sure, as it was their responsibility, to, if they are arranging for a delivery, to give clear instructions as to where to leave the package out of sight, with a neighbouring house where someone would definitely be in or else to not deliver it at all and the have the recipient go and collect it e.g. from the local post office).

The same I’m sure will be true for “the epidemic of knife crime” we’re currently being told we’re experiencing in London right now. I’d be willing to bet £1 that anything and everything is being done and told to “victims” to get them to report “knife crime” but in a year or so, to “prove” that this- or that- police or government activity is “working” there’ll be subtle discouragement. Not that there isn’t a problem with knife crime and there aren’t many genuine crimes and genuine victims of course. But as for establishing a true baseline and a true trend, that I suspect is very problematical due to political motivations.

You can’t open the taps without some splashing. Merkel and others induced more splashing than their constituents wanted and have to let the landscape dry out more to prevent societal mildew and mold. Slower introduction and integration would have seemed to be a more thoughtful approach, without introducing, say, 1,000 newcomers to a village of 400. There are also some exogenous factors to magnify the self-induced troubles. All rather dry and academic even as people decide to uproot their lives in search of betterment.

I didn’t understand this part:

‘First, we ask whether municipalities with larger immigrant concentrations might be associated with higher crime rates, which could (eventually) motivate higher spending on municipal police. Our empirical analysis suggests that migrants are not significantly associated with higher crime rates. It also rules out the possibility that immigration, by increasing security spending, indirectly reduces crime.’

How did they rule out the possibility that municipalities with more migrants keep crime at the same rate by spending more on crime prevention?

Exactly my thought, too.

Doesn’t more spending on more police/security measures typically correlate with reduced crime, regardless of the type of population involved? Hasn’t that correlation been found in a number of US cities?

The article smacks of a pre-conceived conclusion in search of evidence.

Because in municipalities (i guess comparable in size) with less immigrants and less police the crime rate is similar.

This is consistent with the hypothesis that more immigrants lead to more police spending to keep the level of crime similar. They claim to rule out this but it’s not clear how they could do it.

As I read it, the data are consistent with the claim that more policemen doesn’t reduce criminality indirectly as they claim. Criminality is the same. It is so difficult to understand? This also means than you don’t reduce criminality with more police. Criminality rates depend on other things, not migrants, not number of policemen. I find it amusing this is so difficult to understand. If you do international comparisons you will find that criminality rates have nothing to do with the number of policemen.

Should everyone layoff the extra hires then?

Here is some info from a liberal website that contradicts you:

https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/2/13/18193661/hire-police-officers-crime-criminal-justice-reform-booker-harris

“Solid data suggests that even if you take a realistic view of the police, spending money to hire more police officers — an idea espoused by both Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama — is a sound approach to the multifaceted problem of criminal justice. More police officers, in particular, doesn’t need to mean more arrests and more incarceration. More beat cops walking the streets seems to deter crime and reduce the need to arrest anyone. And some of the best-validated approaches to reducing excessive use of force by police officers require departments to adopt more manpower-intensive practices.”

Not that one source is dispositive…..

I agree that the data is consistent with this hypothesis as well. My question was how did they rule out the first hypothesis (more migrants > more police spending > same crime level) in favour of this one.

As a side note, I also think that this is not entirely true that ‘more policemen doesn’t reduce criminality’. While the dependence is not linear surely if you fire all police officers in any big city, the crime will go up, of course until some other arrangement is found.

This is important work, because many climate scientists postulate that the population explosion and climate change are likely to displace a quarter of the planet’s population by mid-century — upwards of 2 billion people. However, I’m afraid that this study over-simplifies the problem of fear and conflict engendered by mass-migration.

It fails to account for whether immigration in Italy is driven by a need for workers or by refugee migration (are immigrants seen as “needed” or as invaders?).

It fails to account for age and gender of the native groups and of the migrant groups (might an older female might be more fearful of an influx of young unattached men?).

It fails to account for how acceptance of more repressive policing might explain the drop in crime rates despite rises in migration, and what the limits of police repression might be (didn’t most people in Germany feel “safer” under Nazi rule — until they didn’t?).

Finally, while the paper features a good discussion on how certain kinds of cultural diversity may undermine social cohesion, it fails to discuss the effect of non-organic population growth and crowding on feelings of safety and security (if migrants often arrive already feeling unsafe and insecure, can overcrowding compound their fear and spread it to the native population?).

I think this research is accurate as far as it goes. But I also think it is virtually sterile. It strikes me as hypocritical for western sociologists to ignore the bigger global picture and focus on simply the desperate immigrants flooding Europe. Clearly, they are no more criminal than the domestic population. It seems pretty criminal for a coalition of angry Swedes to grab bludgeons and march to the train station where they thrashed a group of cowering immigrants fleeing the war in Syria. Maybe with exhilarating memories of clubbing baby seals with grampa. And what of those rape reports? Were they no more prevalent that domestic rapists? The bigger global picture is undeniably criminal. It is that the prevailing western powers have decided they don’t trust foreign countries to manage critical resources, aka oil. And their war has been going on since 2002. Maybe western countries, when flooded with immigrants, are actually projecting their own brutality – as invaders. I recommend lobotomies for all.

I think that we have to be careful with this sort of generalization. It might be true for the educated middle-class families fleeing Syria, but not true for young, unattached, men fleeing other conflict zones, such as we have seen crossing the Med into Southern Europe.

Young men are more prone to criminality than are the general population, and there is plenty of research that backs this up. Add in the social disruptions and trauma caused by the “criminal” globalization of capital and extraction of natural resources, and those traumatized young men can be much more criminal than the domestic population.

However, as you correctly point out, this begs the question of why there is mass migration from climate change and conflict in the first place.

Might as well post a link to the latest (and possibly also the last) study done in Sweden about the subject:

https://www.bra.se/publikationer/arkiv/publikationer/2005-12-14-brottslighet-bland-personer-fodda-i-sverige-och-i-utlandet.html

Click on the link for the PDF, the English summary begins on page 70.

Thanks, Susan the other! Some perspective!

Fig. 1 has been reproduced at a completely illegible resolution. A shame because I wanted to study it.

My brother, a working class, conservative, Vietnam veteran lives in the same house he bought almost 50 years ago when he returned home and married. He does not like change, diversity or foreign people. He never travels from New England unless absolutely necessary. When he bought his home the neighborhood was majority white working class like himself. The neighborhood is now still working class but majority immigrant, non-white, non-english speaking and from many different countries. He gets along with people and is not racist but he still hates the situation and believes it is much less safe. What he really resents is visiting me in an almost pure white middle class suburb loaded with liberal Democrats like myself who are constantly extolling the value of diversity while he hates it but is drowning in it

I think it’s pretty well established that in most countries fear of crime bears little or no relationship to actual crime rates, or changes in them. I’d be surprised if Italy is very different. Since the article doesn’t give any details about the crime statistics, it’s impossible to meaningfully relate them to immigration. It’s worth adding that, as well as the media, peoples’ opinion of the prevalence of crime is related to their personal experience, or that of people they know. In recent years, the Metro in Paris has become less safe, with various problems including gangs of Rom children pickpocketing. Since they are below the age of criminal responsibility, there’s not a lot the Police can do directly. And of course resources devoted to tackling new forms of crime like that have to come from somewhere else, so often leading to the neglect of other crimes elsewhere.

Are there studies confirming the claim that

In Sweden it has been decided that no more public funding research is to be made available for studies of that so conspiracy theorists have for some reason come to suspect that the result of such a study might not be politically correct.

Here is something written by someone who came to Sweden from Afghanistan back in 1997. It is about the Swedish immigration policy:

https://quillette.com/2019/03/04/how-swedens-blind-altruism-is-harming-migrants/

& FYI: clubbing of baby seals were last done in Sweden when Norway was part of Sweden and that was well over one hundred years ago.

I wonder if part of this is the result of fears of material pressures: new immigrants stoke fears of “stealing” jobs from locals. This leads locals to increase police spending, which functionally means more stable, long term state jobs via the police force that also serve to assuage fears of immigrant crime, plus security spending is one of the easier sells to the tight-fisted regarding public spending. Those jobs tend to be taken by natives, or at least more long-term, established immigrants. So a sort of light fascism, state intervention to protect the incomes of the ethno-natives while putting more surveillance and police action pressure on the “others.”