Yves here. I’d be curious to see what readers think of this study. It appears to have a huge bias in that it not only sampled only MSM readers, but the examples of news outlets it cites as representative of where the study ran (New York Times and NPR) suggests the research was heavily biased toward the top 10% that Thomas Frank eviscerated in his book Listen, Liberal.

Moreover, the researchers created tweets and solicited comments. There may be a bias in terms who chose to respond versus remained silent (I confess to not having read the paper because you have to provide an e-mail address, and I am not keen about that, so I am relying on the author’s summary).

Finally, the hashtags were added as decoration at the end, in bold. That gives the impression they were sponsored by the hashtag, as if the hashtag were a political organization (as opposed to sympathetic people using a phrase with a hashtag as shorthand for a particular issue). As anyone who has used Twitter even occasionally knows, this is seldom the way hashtags appear. They are usually integrated into the message text. Moreover, the study chose the two hashtags with lots of opponents, so even if these findings valid for #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo, it’s not clear that they can be generalized to hashtags on less charged topics…like #Brexit, where the use of a hashtag doesn’t signal a position on the topic.

Having said that, I very rarely use hashtags when tweeting (not that I tweet often to begin with), since searching on a word or phrase will pull up matching tweets. The times I do so is typically when a hashtag is trending and I want to help extend its time in that position.

By Eugenia Ha Rim Rho, Ph.D. Candidate in Information and Computer Sciences, University of California, Irvine. Originally published at The Conversation

Whether you’re a conservative or a liberal, you have most likely come across a political hashtag in an article, a tweet or a personal story shared on Facebook.

A hashtag is a functional tag widely used in search engines and social networking services that allow people to search for content that falls under the word or phrase, followed by the # sign.

First popularized by Twitter in 2009, the use of hashtags has become widespread. Nearly anything political with the intent of attracting a wide audience is now branded with a catchy hashtag. Take for example, election campaigns (#MAGA), social movements (#FreeHongKong) or calls for supporting or opposing laws (#LoveWins).

Along with activists and politicians, news companies are also using political hashtags to increase readership and to contextualize reporting in short, digestible social media posts. According to Columbia Journalism Review, such practice is a “good way to introduce a story or perspective into the mainstream news cycle” and “a way to figure out what the public wants to discuss and learn more about.”

Is this really true?

Our Experiment

To find out, we conducted a controlled online experiment with 1,979 people.

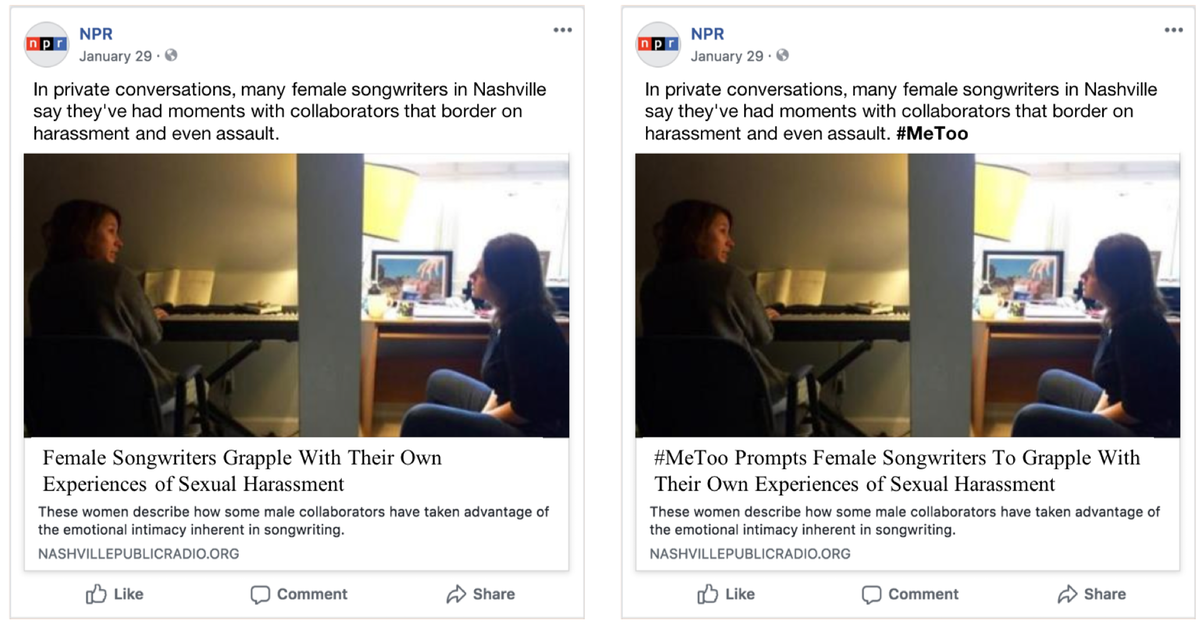

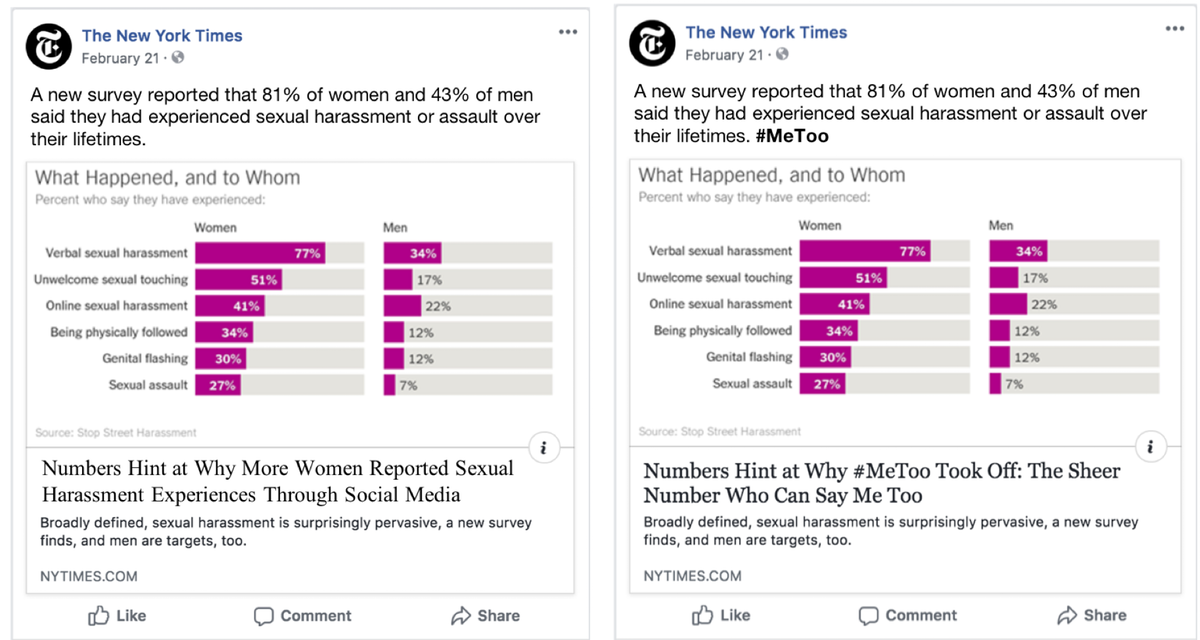

We tested whether people responded differently to the presence or absence of political hashtags – particularly the most widely used #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter – in news articles published on Facebook by major news outlets, such as The New York Timesand NPR.

We randomly showed each person a news post that either contained or excluded the political hashtag. We then asked them to comment on the article and answer a few questions about it.

We discovered that political hashtags are not a good way for news outlets to engage readers.

In fact, when the story included a hashtag, people perceived the news topic to be less important and were less motivated to know more about related issues.

Some readers were also inclined to view news stories with hashtags as more politically biased. This was especially true for more conservative readers, who were more likely to say a news post was extremely partisan when it included a hashtag.

Similarly, hashtags also negatively affected liberal readers. However, readers who identified themselves as “extremely liberal” did not perceive social media news content about gender and racial issues as partisan, regardless of hashtag presence.

Political Moderates

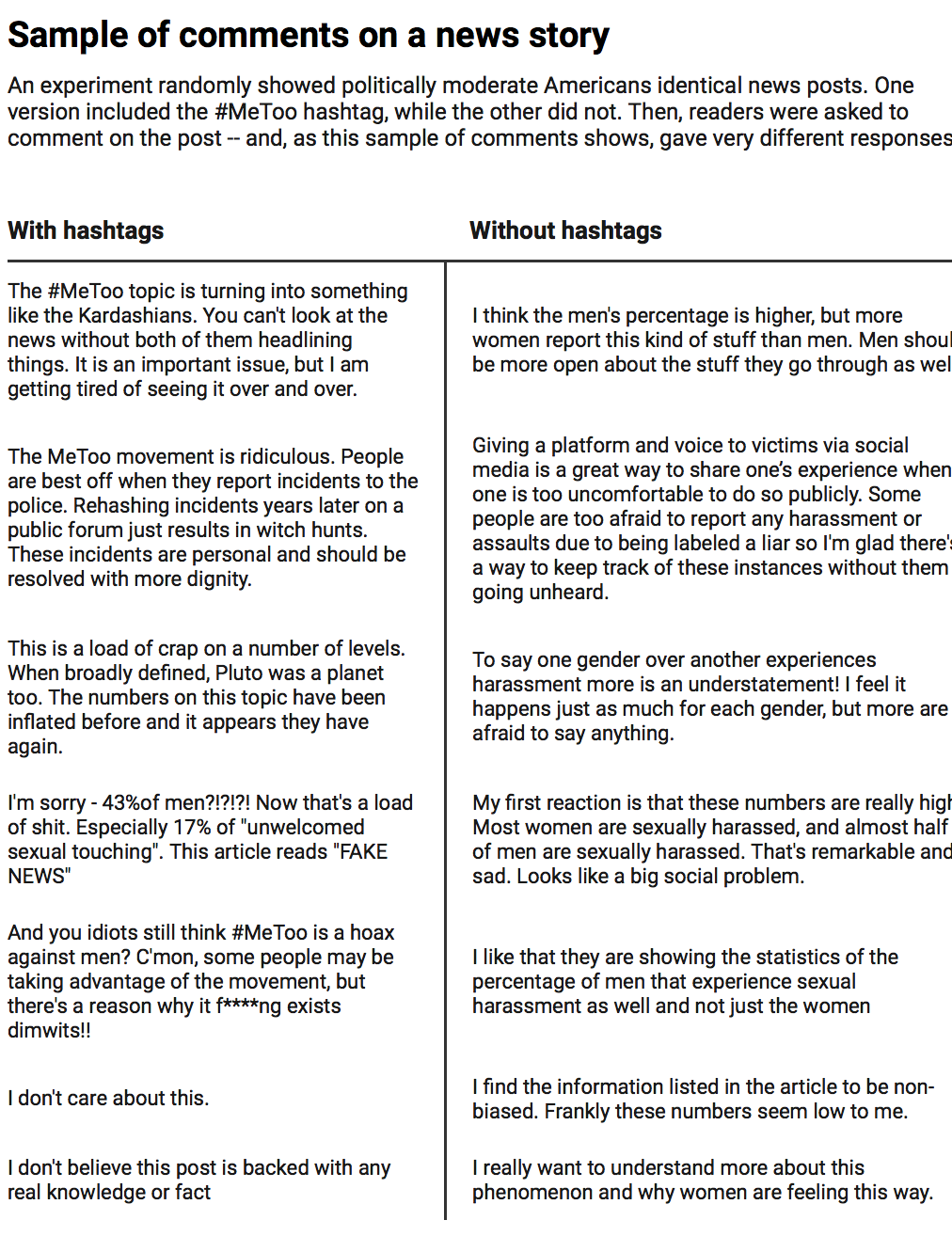

What really interested me was the reaction from people in the middle. People who identified as politically moderate perceived news posts to be significantly more partisan when the posts included hashtags.

In fact, in their comments, politically moderate respondents who saw news posts with hashtags were more suspicious about the credibility of the news and focused more on the politics of the hashtag.

For example in the hashtag group, politically moderate people repeatedly mention the hashtag without substantially engaging with relevant social issues:

“The #MeToo topic is turning into something like the Kardashians. You can’t look at the news without both of them headlining things. It is an important issue, but I am getting tired of seeing it over and over.”

By contrast, when hashtags were absent, readers were more likely to discuss the core ideas and values the hashtag was originally meant to represent.

“Giving a platform and voice to victims via social media is a great way to share one’s experience when one is to uncomfortable to do so publicly. Some people are too afraid to report any harassment or assaults due to being labeled a liar so I’m glad there’s a way to keep track of these instances without them going unheard.”

The language used by participants from the hashtag group in their comments was more emotionally extreme. Even those who seemed to be in favor of the hashtag movement used aggressive language to convey support of the movement and referred to those against it as “You idiots,” claiming, “there’s a reason why [#MeToo] f****-ing exists, dimwits!!”

Fostering Better Online Discourse

These findings show that politicians, activists, news organizations and tech companies cannot take common social media practices for granted.

Even a simple practice, like branding a social topic with a catchy hashtag, can give off the impression to the public that hashtagged content, even news content published by major news companies, is hyper-partisan or untrue.

If we want to build and sustain healthy discussions online, then we need to start questioning how such practices influence the democratic health of the internet.

Using a hashtag can rapidly draw audience attention to pressing social issues. However, as our study shows, such viral momentum may be detrimental to online discussion around pressing social topics in the long run.

This makes sense. A hashtag aims an article at people who have already accepted the validity of the hashtag.

#MeToo and #BLM are both essentially branded campaigns. As Yves said, I don’t think those examples are generalizable to the use of simple topical hashtags. (#womensrights, #rapeawareness, and #policebrutality #civilrights don’t get my hackles up quite as much)

Though, I guess the title of the article does specify “political” hashtags, so probably most of those could be considered partisan by some group.

Even without the hashtag, I react badly when I feel like I’m being advertised to with some focus-tested phrase. I would perceive an article talking about “Medicare for All” a lot differently from one that spoke about single-payer / publicly-funded healthcare. And I feel this way about causes I agree with.

I’d supply an email to read the study but it looks like they want $15. LOL no thanks

+1.

I think a precondition is that the news itself makes people less likely to believe it. The hashtag just finishes it off. After all, people are already suspicious to begin with, knowing that they’ve been completely bullshot since Cronkite retired.

Right. But not so much the news itself as the clear manipulation of it by those in power which includes social media moguls such as Twitter. The hashtag is somehow a particularly rich target for a more general resentment at these mogul entities and what they deliver. Not to mention that Twitter itself, (I never use it so my experience is limited to NC examples) has the problem of condensing everything with the occasional (or not so occasional) negative result of reducing things to caricature.

But without these preconditions, as you point out, even such artificial things as hashtags used as half slogan, half identifier, would probably not inspire such skepticism in particular (or possibly general) groups.

Twitter, YT and Giggle are the only the only social media sites I’ve used extensively, and now I don’t. The problem I’ve seen with all three is that they are based on machine learning algos. They are written by people who think they know what content I will consume to increase their ad revenue, and they are wrong. Over time, the content gets more and more extreme, and not is a good way. YT was once a great reference site for a lot of things, but now my “recommended” videos are cluttered with useless garbage I have no interest in, concentrated on a very few channels the algo has picked up, because I recently viewed a video that had a tangentially related subject. I can’t tell you how many comments I have seen on YT where the user is saying “Why is google recommending this crap?”

Likewise, when I first joined twitter, I could set exactly the people I wanted to see and get their tweets in chronological order. That was it, nothing more. I finally turned it off and cancelled my account when it got to the point of them just streaming me whatever they wanted me to see under the context of some “improved user experience”. Yeah right, see ya. They all have this frog boiling down to a science, literally. They are extremely effective at introducing small tweaks and changes over time that are hardly noticeable. If they have to make a big one, it will be full of “oh gosh, maybe we made a mistake, we will just tweak this and that” but never, ever “let’s turn it back to the way it was.”

The crapification of Google news has been well chronicled here. 10 years ago it was a great service. Now it is nothing more than an MSM amplifier set to 11.

Use these “services” at your own discretion. I have no interest in participating in oligarch faux-hipster driven mind control games at a societal level. And make no mistake, that is what these social media apps are.

Sh..t. ff and dam! Great stuff, thanks. Learned more in your few paragraphs than in as many books.

Our ‘lords’ continue their assault.

I have as little to do with Twitter as possible, and indeed most of my interaction with it come from this site. In turn, that’s because I don’t like being harassed and shouted at, which is what the hashtags discussed in the article do.

It’s useful to consider a hashtag as a pre-emptive attempt to get you to accept a certain truth about a certain story. In this sense, hashtags are like headlines, but they go beyond the organic relations that headlines have (or are supposed to have) with their story. It’s rather as though you were reading a story on the internet with the headlines “Trump is Innocent”, only to have it replaced before your eyes by one saying “Trump is Guilty.”

Most controversial hashtags, like the ones here, are more like advertising or political slogans, and they attempt to coerce you into thinking in a particular way and often behaving in a certain way as well. I was approached by an aggressive beggar demanding money earlier today, and that’s not a bad metaphor for hashtags – or at least these two: “It’s all about me” and “Give me the Money.”

I think they’re on to something, but the study, for the reasons Yves points out, is useless as are the conclusions, particularly in their assumption of broad homogeneity of response.

As many on this site know, hashtag originates (for the scope of this article) from a computer science method of expediting storage and retrieval of items in a set based on the process of hashing the name to a numerical value that can be used as the (somewhat unique – collisions require special handling) index of an array. From this to another way of expressing the notion of identity, as in moniker that captures the gist of the content is a short step.

And on Twitter, it’s catchy, or at least that’s the intent, as is often the case on the internet when computer terms are repurposed for general consumption. Nor is it far fetched to assume from there, that people come to have some (more or less unconscious) resentment at the use of catchy, camp, vogue, monikers as a way of referring to often important issues in life.

Re: “A hashtag is a functional tag widely used in search engines and social networking services that allow (sic) people to search for content that falls under the word or phrase, followed by the # sign.” So howcum all the ones I see have the # sign first? Who writes this crap?

There is so much wrong with this study that I am surprised that any journal that wants to be considered serious would pick it up. Was it peer reviewed? Perhaps if I could read the original study, I would change my mind on some of these failings but I’m not going to pay $15 for a study that prima facie seems to be valueless.

Just a few points:

First of all, where is the definition of political moderate? And how did they test that the responses they received were actually from people who met their definition of political moderate? My brother has views that would make him very comfortable in the antebellum South, yet he will swear up and down – on his Bible, of course – that he is a political moderate. People lie to themselves and others for a variety of reasons – those reasons are variables that must be controlled, yet I see no evidence the authors of the study even tried to do that, rather they let people self-identify.

Second, I don’t see how they gathered data or how they evaluated the data they received, perhaps the original article would have told me that. Is their data reproducible? Did they use the correct statistical models? Did they test their hypothesis with other hashtags, perhaps some that were not as emotionally charged? How does one come to a broad causation based on what appears to be one data point?

Third, how did they choose which comments to evaluate and publish in their study? Seems to me the comments in the left column are from emotionally charged people while those on the right are not. How was the data selection vis a vie comments, done? We all know from Disqus and other comment engines that there is a limited segment of our population that responds emotionally to every story and although their numbers are small, they seem to take over comment sections. What was done to analyze and account for that?

And I could go on.

I don’t know if the authors’ conclusions are true, but I don’t see that the evidence is there to confirm one way or the other. Perhaps they are just trying to convince us that what they believe is true, but I’m definitely not convinced at this point. I see it now as just another example of someone trying to “scientificify” their own beliefs.

I never read Twitter, but I regard it as a good thing (probably) because it acts as a kind of sewer. Back in Usenet days, it was noticeable that a substantial portion of the participants were not interested in thought, experience, evidence, logic, truth, beauty, or even description, but in one-liners, usually hostile, usually based on pop culture — a kind of mental chaff blowing in the wind, motivated by a desire to score. Today, these people and the bots which represent them would otherwise be infesting other realms of discourse. Instead they’re twitting each other. Good.

I had never thought about Twitter’s value as a sewer before.

Thanks!

I can’t comment on the study, but I will say that the mere presence of a political hashtag anywhere tells me “idiot” or “DC reporter” (not much difference there). And no, I don’t use any social media at all. +1 to the sewer analogy.

The tells in this biased article are: “political moderates” and “Better Online Discourse”. Both terms are extremely subjective. Moreover, they are often used by corporate Dems to ‘other’ their left-wing adversaries. They do this by painting progressive movements and reforms as delusional and unreasonable.

you have to provide an e-mail address

Use mailinator.com to get throw-away e-mail addresses.