Yves here. Remember Libra, Facebook’s planned entry into the cryptocurrency game? Facebook grandiosely threw a bunch of fintech gimmicks like blockchain and stablecoin and super low cost international transfers into a bag and acted like it would add up to a ginormous business. Facebook does money! What’s not to like?

We haven’t heard much about the notion of late, and there’s a reason. Aside from pretty much every large economy financial regulator going to war with it, the idea was half baked. And then virtually all of its partners who actually knew anything about payment systems, like PayPal, Mastercard and Visa, bolted from the project. As we wrote in October:

Before we go much further, one of the obvious flaws in the Libra project is that Facebook (and too many members of the press) don’t understand the difference between a cryptocurrency and a payment system. Facebook seems to have naively believed if it could just launch a really big cryptocurrency, with its big customer base, they would easily be persuaded to trade it among themselves.

Ahem, aside from not having considered “Who want to have to trade a volatile foreign currency into what I need to use to pay my bills and incur FX transaction costs and tax issues every time I do so,” payment systems have to do a hell of a lot more things that just create a pile of something people might if you are lucky buy and sell. You need to provide recordkeeping and anti-fraud protections, adhere to Know Your Customer and anti-money laundering rules (unless you want to be a financial outlaw), and provide information to the tax man. That’s only a partial list…

Economists have continued to ponder what if anything newfangled forms of money and transfers might do for smaller and developing economies. This VoxEU post concludes, as we did, that the “stablecoin” gimmick doesn’t solve the problem that people in real economies deal in their local money, and trading in and out of a foreign currency like stablecoin entails costs and risks.

The post also deflates a lot of fintech claims. While it points out that digital money products can be very beneficial within a country, lowering costs, speeding clearing time and thus making it more viable for more people and businesses to participate, the main benefit for international transactions is more efficient linkages to existing payments architecture.

By Erik Feyen, Head Global Macro-Financial Monitoring in the Finance, Competitiveness and Innovation Global Practice, World Bank; Jon Frost, Senior Economist, BIS; and Harish Natarajan, Lead Financial Sector Specialist in the Finance, Competitiveness and Innovation Global Practice, World Bank. Originally published at VoxEU

Proposals for global stablecoins have put a welcome spotlight on deficiencies in financial inclusion and cross-border payments and remittances to emerging market and developing economies. This column, part of the Vox debate on digital currencies, argues however that stablecoin initiatives are no panacea. Moreover, they pose particular development, macroeconomic and cross-border challenges for emerging market and developing economies. It remains to be seen whether stablecoins can offer a decisive comparative advantage over fast-moving fintech innovations in these countries that are built on or improve the existing financial plumbing.

From the ancient Indian rupya, to cacao beans in the Aztec empire, to the first paper money in China, the countries that are today referred to as emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have seen innovation in money and payments for centuries. In recent decades, physical cash and claims on commercial banks (i.e. deposits) have become the main vehicles for retail payments around the world (Bech et al. 2018). Compared to physical cash, commercial bank money provides more safety, enables remote transactions, and allows banks to extend other useful financial services.

Yet for retail users, especially in EMDEs, commercial bank money poses at least three key challenges. First, it requires a bank account – access to which is far from universal. The poor often lack the proper documentation to comply with banks’ customer due diligence (CDD) requirements. In some cases, they live too far from a bank branch, or find the maintenance costs or minimum balances too onerous. As a result, the poor rely heavily on cash, which perpetuates informality.

Second, despite improvements in recent years, financial institutions in many EMDEs face limited competition. This concentrated market power results in limited innovation and poorer, more expensive financial services. Together with past experiences of financial crises, this contributes to a lack of trust in the formal banking system.

Third, many households in EMDEs depend on low-value cross-border remittances from family members working abroad. Remittances exceed official aid by a factor of three and are on track to overtake foreign direct investment inflows (World Bank 2019). Specialised money transfer operators have emerged to provide near instantaneous transfers, and to reduce the costs for sending money over time. Yet it still costs about $14 on average to send $200 back home (World Bank 2019). This is largely because of the role of cash on both sides of the remittance (‘cash-in, cash-out’). Micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) and individuals participating in cross-border trade in EMDEs have an even bigger problem. They are dependent on banks and specialised providers that in turn often depend on the slow and opaque correspondent banking system.

Enter Stablecoins

Various crypto-assets claim to address deficiencies in the existing financial system. Many are vying to become a new form of digital money that can be securely sent and received over the internet, by anybody with a phone or internet connection, and with the convenience and cost-effectiveness of an email. Some initiatives target cross-border payments, particularly remittances, in EMDEs. By cutting out financial intermediaries, such proposals aim to empower users and make domestic and cross-border payments more efficient. This may be particularly relevant for country corridors hit by a decline in correspondent banking relationships (CPMI 2016, IMF 2017, FSB 2019a), and for those countries with growing participation in the digital economy but no corresponding growth in access to e-commerce-enabled payment mechanisms.

Crypto-assets have suffered from various impediments, including high price volatility and scalability challenges, which prevent them from being adopted as a mainstream means of payment or store of value, much less a unit of account (see BIS, 2018). In response, a diverse family of so-called stablecoins has entered the fray. Most stablecoins attempt to maintain a stable value relative to a fiat currency (like e-money or a currency board) or a basket of fiat currencies. To maintain a stable value, most initiatives adopt a collateral approach using bank deposits, government securities or crypto-assets (Moin et al. 2019). This would be no small feat as the eventful history of broken currency boards and pegs has shown. Further, stablecoin systems that can tap into the massive user bases of platform companies may employ network effects to drive rapid adoption on a global scale.

However, as pointed out by a recent G7 report and ongoing FSB work, stablecoins pose a wide range of risks related to, among others, legal certainty, financial integrity, sound governance, the smooth functioning of payments, consumer protection, data privacy, tax compliance, and potentially monetary policy and financial stability (G7 Working Group on Stablecoins, 2019; FSB, 2019b). Moreover, stablecoins face many of the same obstacles that other players have faced with transaction accounts. Further, they need to contend with new challenges of their own depending on the scale of adoption and their use as a means of payment or a store of value.

Particular Challenges for EMDEs

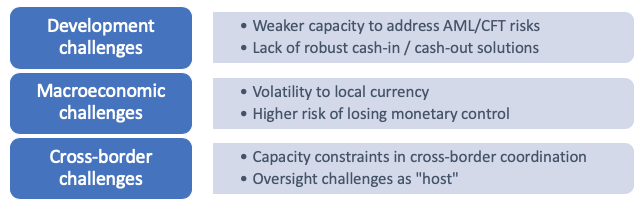

Several issues related to stablecoins are exacerbated in EMDEs. Authorities are confronted with six main development,1 macroeconomic, and cross-border challenges (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Particular challenges of stablecoins for EMDEs

First, stablecoin systems could pose severe anti-money laundering/combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) risks (FATF 2019a). Stablecoin systems need to comply with the standards of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to mitigate their use for illicit financial activities. These were recently amended to cover virtual assets service providers (VASPs) such as crypto-exchanges, who will now also need to conduct CDD (FATF 2019b). In their current conception, most stablecoins projects do not seek to link ‘accounts’ to real-world identities. This raises regulatory arbitrage concerns if significant volumes of transactions occur in a peer-to-peer fashion rather than using VASPs or other financial intermediaries. While this affects authorities around the world, EMDEs may have more difficulty keeping pace and adjusting their surveillance, regulatory and supervisory frameworks, given resource constraints.

Second, like branchless banking and e-money networks, stablecoin systems would need to offer robust and secure ‘cash-in/cash-out’ functions between stablecoins and fiat currency through physical agent networks – for mobile money this accounts for about 70% of transactions. This is challenging if distribution networks are not equipped to handle crypto-asset or stablecoin transactions, lack geographical coverage or are prone to cyber-attacks. So far, it is unclear whether stablecoin systems would work on simpler ‘feature phones’ and in locations with poor connectivity, or whether they could better address the challenges posed by a lack of ID for onboarding the unbanked, particularly in remote locations.

Third, fundamentally, stablecoins will fluctuate against local currencies in EMDEs. This inhibits their adoption for daily payments since prices will remain denominated in local currencies in all but the most extreme cases. If used for debt contracts, this is a new form of foreign exchange (FX) lending. FX lending has been at the heart of many financial crises in EMDEs.

Fourth, depending on the prevalence of their use domestically, stablecoins import the monetary policies of the fiat currencies in the basket that may not be optimal for most EMDEs and could thus impinge on their monetary policies. ‘Stablecoin-isation’ could mean less effective monetary transmission and, in the extreme, countries that face shocks – political, economic or financial – could face deposit outflows from banks and capital flight. This would amplify instability and render policy measures less effective. Countries with large cross-border inflows in stablecoins may face difficulties to maintain international reserves in hard fiat currencies. This has implications for the functioning of FX and interbank markets, which are shallower in EMDEs. Liquidity and redemption shocks may thus create disruptive spillovers.

Fifth, stablecoin systems may combine elements of multiple regulatory frameworks, for example for payment systems, bank deposits, e-money, commodities, FX, and securities. In some jurisdictions, there may be gaps as no specific framework would apply. This may create an unlevel playing field if countries adopt different regulatory approaches. EMDEs may have more difficulty to allocate proper resources to adjust their policy frameworks, adopt proportionate supervision, and engage in coordination across borders.

Sixth, EMDEs will likely act as a ‘host’ to most entities in a stablecoin system, which may be headquartered elsewhere. As such, authorities may lack control over stablecoin payments that involve residents. When domestically adopted at scale, this could inhibit monitoring of risks and effective oversight of payments to prevent illicit use and foster financial stability, as mandated by international standards. Moreover, it raises questions on consumer protection and redress mechanisms.

Many of these challenges can be addressed, or at least mitigated, by adequate policies. These could include additional resources on AML/CFT supervision, regulations to limit currency mismatches, and further international coordination. Yet, such policies take time and resources to be enacted, and the potential opportunities from stablecoins have to be weighed against the substantial risks.

Technological Advances Are Already Enhancing Inclusion and Efficiency

Fortunately, stablecoins are not the only game in town. In recent decades, technological advances have given EMDEs an opportunity to ‘leapfrog’ into the digital economy (IMF and World Bank Group 2018). Fintech facilitates the digitisation of money, making accounts and payments services more accessible, safer, cheaper, more convenient, and closer to real time. As a result, in sub-Saharan Africa, the share of adults with an e-money account nearly doubled from 2014 to 2017, to a level of 21%. Globally, 52% of adults used digital payments in 2017, up from 42% in 2014 (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2018). Across all levels of economic development, the share of unbanked adults and the costs of remittances are falling. Several factors have facilitated these developments.

First, policymakers are facilitating fintech innovation and adoption by updating policy frameworks and promoting digital literacy. Many countries are working on digital ID systems, which provide the opportunity to bring the over one billion undocumented people into the financial sector and promote transaction security. The experience with Aadhaar in India is particularly instructive (D’Silva et al. 2019).

Second, authorities are upgrading payment infrastructures with ‘fast payments’, allowing banks and eligible non-banks to offer 24/7, near real-time payments (Bech et al. 2017). Moreover, ‘open banking’ initiatives allow for third party-initiated payment services,2 often de-coupling transaction accounts from banks and empowering customers. This can help boost competition.

Third, there is a global rise of non-bank e-money issuers such as e-commerce platforms or telecom operators with large user bases that benefit from network effects. E-money is a bridge to commercial bank money, as in most countries it needs to be fully covered by commercial bank money. E-money can be conveniently stored on and exchanged from a phone or online and funds can be transferred through digital channels as well as physical agent locations. This is better suited for many consumers in EMDEs, particularly those who live in remote areas.

Fourth, feeling the pressure to innovate, incumbent banks and payment providers are embracing fintech to improve their services so consumers can conduct payments more conveniently, faster and 24/7. For example, many incumbent banks are joining hands, in some cases also with non-banks, to develop fast payment networks and offer access to their deposit-based products via mobile apps (Petralia et al. 2019).

Finally, new fintechs have extended the money transfer operator model for cross-border transfers by connecting to local payment infrastructures and banks or e-money providers on both sides of a transaction. Further, the global financial messaging network SWIFT has launched the Global Payments Initiative (SWIFT gpi) to bring transparency, speed and reliability to correspondent banking transactions.

Conclusion

Stablecoin arrangements aspire to improve financial inclusion and cross-border remittances – but they are neither necessary nor sufficient to meet these policy goals. It is unclear whether they would offer lasting competitive advantage to rapidly evolving digitalization of money and payments services that are built on top of or aim to improve existing financial plumbing. Innovations such as digital ID, e-money, mobile banking, open banking, and Faster Payment system may be adequate in a domestic setting. The development of SWIFT gpi and the integration of Faster Payment systems could help improve cross-border payments, although more work is clearly needed.

Meanwhile, stablecoins face various challenges and pose new risks, particularly in EMDEs. Thus, authorities may consider limiting or even prohibiting the use of stablecoins as a means of payment, and bar regulated entities such as banks and agent networks from holding stablecoins or offering stablecoin services.

Some countries have reacted by accelerating their investigations into a central bank digital currency (CBDC) for consumers. However, a new digital equivalent to cash also raises various challenges (CPMI-MC 2018) and it is not yet clear whether it is necessary or desirable.

Taken together, perhaps the most important contribution of stablecoins thus far is that they have drawn greater – and welcome – attention to the challenges of financial inclusion and more efficient cross-border payments and remittances. This highlights the efforts underway to strengthen monetary and financial stability frameworks; promote an enabling regulatory environment for fintech; upgrade payment infrastructures, particularly across borders; and ensure a global regulatory level playing field through greater collaboration.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily of the World Bank or Bank for International Settlements. The authors thank Raphael Auer, Stijn Claessens, Sebastian Doerr, Matei Dohotaru, Alfonso Garcia Mora, Leonardo Gambacorta, Marc Hollanders, Yira Mascaro, Tara Rice, Hyun Song Shin, and Mahesh Uttamchandani for comments.

See original post for references

I don’t know what part of “states issue fiat currencies” these people don’t get.

Not to mention the “states jealously guard their monopoly over their fiat currencies” part …

And even if you could develop a “stablecoin” that was actually stable and was cheap to use for anyone to make payments over the internet, it would essentially be a global currency, which is the last thing any decent globalization proponent wants.

Now with the shape sovereign nations are in these days, I could see a digital currency company trying something like this and sneaking it through before those in charge of making regulations for sclerotic sovereign nations know what’s going on. That, or the lawmakers/regulators are on the take and look the other way. See Uber, AirBnB, etc for companies allowed to flout the law globally for profit.

But no self-respecting banker is going to allow this to happen, not when they are in the business of currency arbitrage. That’s one big rice bowl being put in jeopardy and with bankers calling the shots again these days, they’d start a war before allowing a global digital currency that they have no stake in.

Financial globalists want to have their cake (free flow of capital in global financial markets) and eat it too (no global currency).

eg,

I agree, and the consequence of not jealously guarding their monopolies is that they hand control of their distribution — everything they do and everything they have (ok, everything tradable) — over to strangers. When a local bank isn’t subject to competition, then the bank is run by a grandee who might be persuaded to act at times in the nation’s interest. Opened up, the bank can be swamped by global competitors who are for sure acting in no-one’s interest but their own.

An EMDE that’s going to modernize its money has to develop a secure cellphone network, its own datacenters that it can run, and of course reliable legal and financial institutions.

Putin’s recent constitutional proposals may contain a lot that EMDEs can learn from.

So I can’t help wondering what would happen to the beautifully intricate coordination of bio-ecosystems on this planet if they all were monopolized by some higher power strangling them and controlling their critical source of energy – for amoebas it would be ATP; for fish it would be water; for trees it would be carbon dioxide, etc. And for us symbolic idiots it would be the biggest oxymoron of all-time – money. And to cut them off from their oxygen would create a moveable desert of lifelessness and vanished synergy. The planet runs on synergy, otherwise we would turn into a stagnant pool of excrement – which we are rapidly doing. God forbid that we use money, in some globalized digitalized form, to “boost competition” – create unsustainable volatility without synergy (now simply a costly externality in our quest for transitory profits); all for the sake of pointless, toxic and fatal liquidity. Which has nothing whatsoever to do with reality. Nor cooperation. Nor the impulse for credit. Since when did credit seek to destroy the entire planet?

Some thoughts from a SSA country whose government is currently obsessed with cashless payments, fintech and inclusion.

We all already concluded it’s bollocks for the majority. 1. Most of us are poor and rural with zero access to banks 2. Most of us have too little money to make deposits worth it 3. Arbitrary taxes and fees with the cashless payments makes it prohibitory 4. Our telcos has long figured out how to include millions of ppl into the financial system 5. The successful fintech companies here do payments for Uber and bolt so you already know they serve a very small minority 6. Our banks are fast and I can see them usurping current fintech firms

I’m coming up blank for definition of “SSA”.

Sub-Saharan Africa.

I’ll wade in because I’ve been at the coalface of this for the last 6 or 7 years.

1. It’s very unclear to me the way forward with a debt-based currency system if lenders are to receive zero in exchange for extending credit (zero interest rates). Right now we have a huge global bandaid on this in the form of central banks, that have no ability to underwrite, agreeing to put risk on their balance sheets regardless of the borrower’s ability to repay. If you have a truly sovereign issuer (like China) you “solve” this because the state is issuing the scrip essentially directly. Under the Constitution the U.S. is also supposed to run like this, with the Treasury issuing the currency, but instead we have commercial banks issuing the money. This means you need a system to defend the solvency of the commercial currency issuers (which we have) but that system is currently only operational because we pretend there is no longer any such thing as borrower creditworthiness (credit issuers can simply pass the hot potato to the CB supposedly ad infinitum).

2. Japan shows this extending to its logical conclusion, since they were the first to engage in this financial parlour trick (quantitative easing). To have a functioning debt-based currency you need a debt market of buyers and sellers. The 10-year Japanese Government Bond used to be the foundation, but there are many days now when the *only* bidder for 10-year JGBs *is the entity that issued those bonds in the first place* (the Bank of Japan). Consult Lewis Carroll while you contemplate that situation.

3. Some supra-issuer like FB, concocting a basket of existing national currencies, is a very silly idea as Yves and others have always pointed out. If I live in Malaysia I can only buy things in ringgit, my landlord accepts only ringgit, and I must pay my government tax in ringgit. Trying to hold and pay with a FB thingy is daft.

4. People tend to think payments is a global business. It’s not. It’s a local business connected by a patchwork of systems designed decades ago. Banks have invested massively to modernize but there’s been serious underinvestment in the systems that connect them, this is largely because banks get to earn a little as funds pass through their hot little hands, so keeping things slow is good. SWIFT have awakened though and have some very good improvements rolling out.

5. Blockchain. Let’s be real, these are simply ledgers. Ledgers that are much slower and much more difficult to secure. Try safely holding encrypted keypairs yourself on a device sometime. Bitcoin of course was supposed to be the great new way forward for payments, now they’re reduced to saying it is “digital gold”. Oh but with heightened regulatory, compliance, tax, AML and security issues. And oh, no customer service. Blockchain partisans forgot one thing: for people to adopt something it must be better. A ledger that every 10 minutes is secured by an anonymous party in mainland China known only by the screen name “friedcat” is probably not that.

> The 10-year Japanese Government Bond used to be the foundation, but there are many days now when the *only* bidder for 10-year JGBs *is the entity that issued those bonds in the first place* (the Bank of Japan).

I may be way out of my depth here, but how is that a bad thing?

Isn’t a system in which the central bank buys back government debt (at zero or near zero interest rate) better than a system in which only private markets are tasked with pricing government debt, which might mean high interest rate, that could then be used to force the government into austerity and budget cuts?

By buying their own government bonds aren’t central banks essentially acting as a firewall against austerity? And isn’t that how Japan has managed to escape austerity policies, even though it has the world largest debt to GDP ratio?

And from an MMT point of view, wouldn’t that also be OK? MMT tells us that governments are not even required to issue debt, so buying it back via central bank would be roughly equivalent to not issuing it, right?

+1 for the friedcat reference – another enduring Bitcoin mystery.

>”for people to adopt something it must be better”

Given your paras 1 and 2, “something better” might be a much easier target in the coming decades. No amount of innovation by SWIFT can fix the sort of fundamental issues you allude to. In the meantime, the would-be alternatives continue to grow and evolve.

I believe that monetarily sovereign nations issue debt as an institutional holdover from gold standard era thinking, and as a “favour” to oligarchic elements of their polity. I don’t believe that it is fiscally necessary.

Which is a convoluted way of saying that the natural interest rate is zero, and central banks have to defend their policy rate from going to zero by issuing bonds.

But Warren Mosler explains this far better than I can

http://www.cfeps.org/pubs/wp-pdf/WP37-MoslerForstater.pdf

Which is a convoluted way of saying that the natural interest rate is zero, … eg

How can the natural interest rate of fiat be known when citizens, except for mere coins and Central Bank Notes, may not even use fiat, but only (in the US) 7000 or so depository institutions?

So the demand for fiat is unjustly and unnaturally suppressed in favor of private bank deposits so there’s nothing “natural” about any resulting interest rate in fiat.

Also, Warren Mosler would provide unlimited, unsecured Central Bank loans to banks at zero percent. But what need for that if the natural interest rate in fiat is zero percent?

So even Mosler admits the “natural interest rate” varies from zero.

Btw, our current banking model is a corrupt relic of the corrupt Gold Standard. Where then are Warren Mosler’s proposals to abolish that model?

It’s very unclear to me the way forward with a debt-based currency system if lenders are to receive zero in exchange for extending credit (zero interest rates). OpenThePodBayDoorsHAL

Zero beats negative and, except for individual citizens up to a reasonable account limit, NO ONE should be allowed to use the Nation’s fiat for free anymore than large trucks should be allowed to use the Nation’s highways for free.

Btw, end welfare for the banks and the rich and there’d be far less need for welfare for everyone else.

… doesn’t solve the problem that people in real economies deal in their local money, Yves

Sadly, and the root of very many problems, that “money”, except for mere coins and paper Central Bank notes, consists of mere liabilities for fiat, private bank deposits, and the banks create those too when they “lend.”

We could have a system where citizens could, along with depository institutions, use fiat in in inherently risk-free account form at the Central Bank itself.

But that would be a slippery slope to ending ALL other privileges for banks (such as government-provided deposit guarantees) and thereby end the ability of the banks and the rich to steal from the poor via government-backed deposit creation.

Stealing from the poor, besides being loathsome, is rather like shooting helpless fish in a barrel. Where’s the sport or sense of accomplishment in that but rather a sense of dread at the Judgement coming for doing so?