Yves here. Wowsers, the uncommon article that upends conventional wisdom. Many armchair pundits have argued that the reason women in the US stopped postponing motherhood was concern about their famed biological clock and/or more women coming to believe that “having it all” was a myth and motherhood was therefore given more weight than doggedly sticking to a career. This article argues that the impact of China import competition on wages made staying in the workforce less attractive.

By Wolfgang Keller, Director of the McGuire Center for International Economics and Professor at the University of Colorado-Boulder and Hâle Utar, Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Grinnell College. Originally published at VoxEU

The 20th century saw a steady increase in the number of women postponing motherhood to enhance their labour market opportunities. Sometime in the early 2000s, that trend ended. This column compares the experience of women in the US and Denmark and finds that women of childbearing age who experienced diminished labour market opportunities because of import competition from China turned towards family life, while men focused on finding a new career path in the labour market. Import competition from China raised the likelihood of marriage for women but not for men.

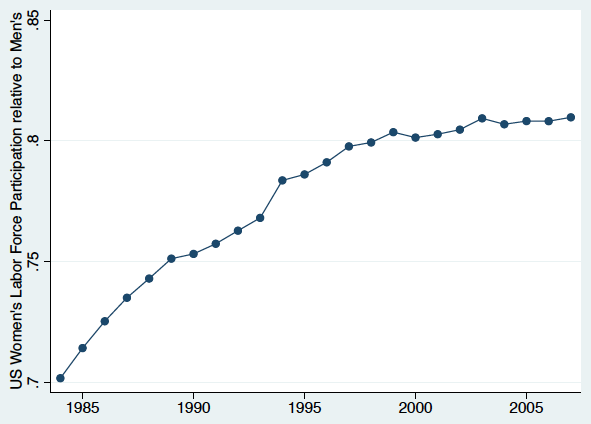

The 20th century saw an equalisation of women’s and men’s opportunities in the labour markets in many countries. Take labour force participation in the US, for example. Shortly after WWII, men were almost three times as likely to be in the labour force as were women; by the year 2008, women’s labour force participation stood at around 83% of men’s, as shown in the top panel of Figure 1.

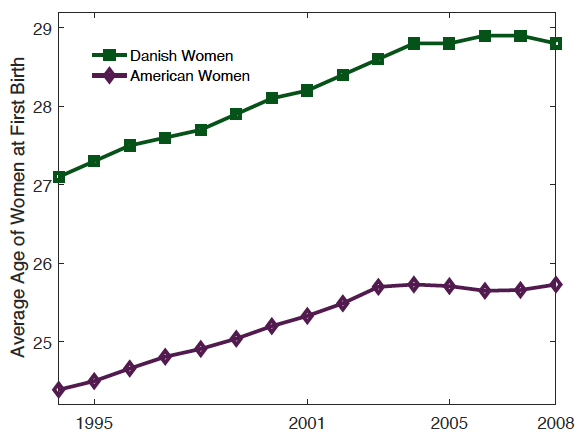

Figure 1 Women’s labour force participation and first-time motherhood

In striking contrast to the strong trend throughout much of the 20th century, there has been little convergence in labour force participation rates across gender since the early 2000s. While a number of factors might play a role (Fortin 2005, Goldin 2014), in this column we argue that changing labour market opportunities should be seen together with family outcomes that determine the work-life balance of men and women. In particular, the lower panel of Figure 1 shows that sometime in the early 2000s, the rise in the number of women postponing motherhood – a choice typically made to enhance labour market opportunities – stopped for both US and Danish women.

Recent evidence shows that differences in the labour adjustment to globalisation made by men and women plays an important role in this change. When faced with a negative labour market shock of a given size, female workers are more likely than male workers to take time out of the labour market for family goals: only women give birth and, in contrast to men, women struggle to achieve their fertility goals beyond a certain age (a constraint we refer to as the ‘biological clock’).

In Keller and Utar (2020), we study the effects that the rising number of exports from China had on Danish workers as the country entered the WTO in late 2001. This intensified import competition from China closed many career paths in the manufacturing sector in Denmark, leaving a switch to the growing service sector as the only viable path. The study investigates how this loss of labour market opportunities for workers due to a plausibly exogenous shock affects fertility, childcare uptake, and the formation and duration of marital unions. Crucially, rising import competition is but one type of labour demand shock that women respond to by establishing a different work-life balance than men due to their biological clock; another instance is job displacement due to plant closure (Del Bono et al. 2012, Huttunen and Kellukumpu 2016).

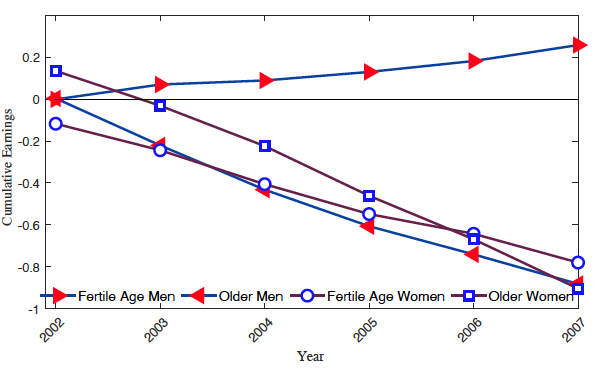

We combined administrative data on all firms and their workers with complete family histories from population registers, which allows us to follow workers from job to job (or unemployment) as they make key family decisions on co-habitation, marriage, divorce, and children. The impact of the negative labour shock is found by comparing labour market and family experiences of workers employed at Danish firms that are hit hard by rising import competition from China with the experiences of less affected workers. Figure 2 shows the impact on labour earnings between 2002 and 2007 for four sets of workers, women and men who are either young or old (fertile-age and post-fertile-age, respectively).

Figure 2 The missing earnings of fertile-age women

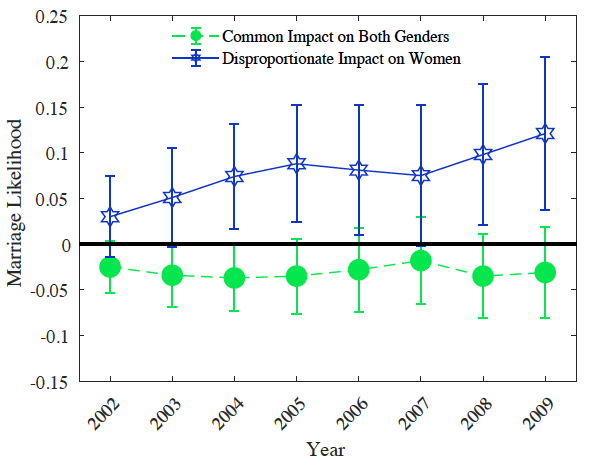

Figure 3 Gender gap in trade adjustment costs

By 2007, labour earnings of affected older men are much lower than earnings of unaffected older men, in line with a negative impact of import competition on earnings. For younger men, there is no comparable impact, because affected young men are able to adjust to the shock by switching to jobs in other sectors without delay. Human capital theory tells us that young workers are more willing than older workers to pay the cost of adjustment because they have a longer career ahead to recoup the investments.

It is striking that the impact of the negative labour shock is very similar for fertile-age and older women: both groups lose about 80% of their initial annual earnings over the course of five years following the shock. As a result, we show that import competition leads to a substantial gender earnings gap, but only among fertile-age workers (Figure 3). Put differently, the advantage of being young disappears for women adjusting to globalisation. What explains the finding that fertile-age women adjust as poorly to the labour market shock as do older women?

One possibility is that women were hit harder than men by import competition from China because women tend to be employed in particularly vulnerable firms, industries, or occupations. Another possibility is that young women have lower earnings than young men because they are more negatively affected by the technology shocks correlated with import competition. Our analysis rules out both hypotheses.

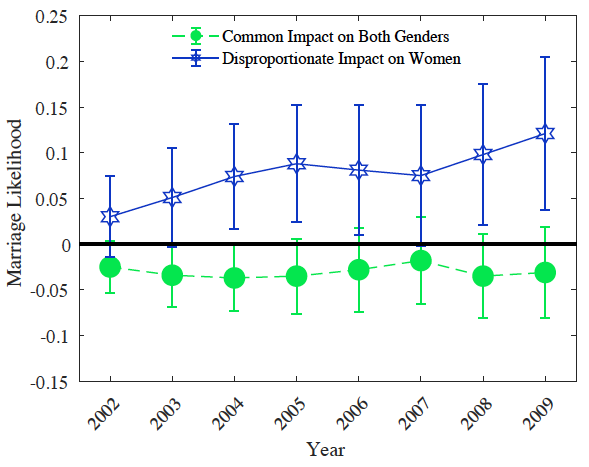

Rather, fertile-age women who experience diminished labour market opportunities because of import competition from China turn towards family life, while men focus on finding a new career path in the labour market. Figure 4 shows that import competition from China raises marriage likelihood for women but not for men.

Figure 4 Impact of exposure to rising import competition on marriage likelihood

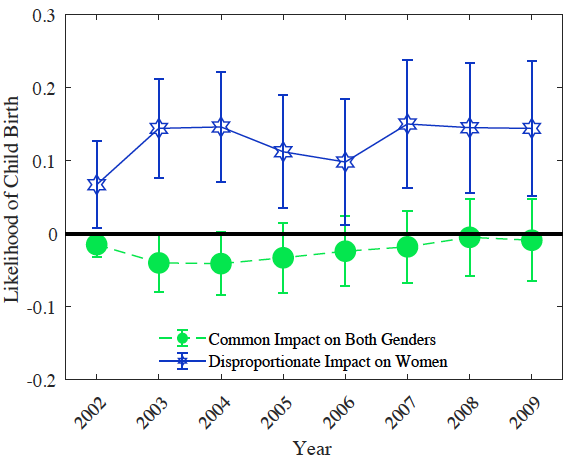

Figure 5 shows that women respond to rising import competition by having more babies; the same is not true for men. Women in Denmark can respond to a negative labour demand shock by increasing fertility in part because the country has substantial insurance and transfer policies that limit personal income losses despite a decline in earnings.

Figure 5 Impact of exposure to rising import competition on childbirth

In our paper, we develop the findings in the figures in a rigorous difference-in-difference framework. We also document that as long as female workers are of fertile age, the tendency to move to family life increases with age, which supports the idea that they are motivated by their biological clock.

The move towards family activities most often happens when women are in a weak labour market position due to import competition, such as unemployment or a spell outside the labour market. This supports the view that the shift of women from the labour market to family activities is induced by lower labour market opportunities.

In sum, our analysis highlights substantial differences in trade adjustment of workers across genders and proposes fertility-related biological differences and the biological clock in particular as a new factor behind the non-convergence in labour market performance indicators across gender.

See original post for references

“Import competition from China raised the likelihood of marriage for women but not for men.”

So whom are the women marrying? I assume that this refers only to women in a certain age bracket so that they marry older men (who are more likely to have higer income)?

This is very interesting, but why do all charts stop 10 to 13 years ago ?

One would think that “average age at first birth” or “labor participation” should be available at least for 2018, if not 2019.

This is a severe detriment to the article IMHO.

Interesting hypothesis. If I recall correctly the economic collapse in Ireland led to a brief baby boom in the following years – the theory (backed by various anecdotes) was that married women who had lost their jobs felt that this was as good a time as any to have a child. So far as I’m aware though it didn’t have any known long term impacts on demographic changes.

Why would an economic collapse be a good time to acquire a massive liability??

For working women there is never a good time. So if you’re out of work for other reasons, that’s a good time to take on the work of motherhood.

But also, a wee bit glib to dismiss children as just “massive liability.” Yeah, sure, they’re costly, but they give back. Perhaps most importantly, they give us hope.

You’re really taking that rational actor theory to heart, huh? I guess humans don’t possess the same innate biological drive to reproduce that every other living species on the planet does.

“The 20th century saw a steady increase in the number of women postponing motherhood to enhance their labour market opportunities.”

Having spent most of my years in the 20th century, I think the author has forgotten the effectiveness of the birth control pill. Women up until that time (the 1960s) often had up to 10 children (if they lived through all those births) and, when the pill was developed, most women took them gladly and had not only fewer children but children later in life and, thus, escaped the exhaustion of birthing and caring for numerous children. Women were not thinking about “enhancing their labour market opportunities.”

Huh? The pill was not widely available until the later 1960s. Most people I knew had 2-4 kids in their family pre-birth control.

Interesting. I suppose it depends on where you grew up and the size of the town.

This is just a side note because it brought back rememberances of all the large families I grew up with.

Growing up in the sixties in a factory town in the NorthEast, for sure at least a little more than 1/2 the kids I grew up with came from families with at least 2 to 4 children (in my class of well over 600, I remember only 3 kids that were of the “only child” status), but many people had families of 5 to 7 or more. Two people I regularly hung out with grew up in families larger than mine, but looking back, 3 seemed to be the most common number.

But I do remember well when birth control pills came out. I grew up in a family of 7 kids and when they became available in the later 60’s, my Mother jumped on them immediately :-)

I grew up in the 50’s, entered college in 63. In our neighborhood, most families had 4,5,or6 kids. My own generation was a dramatic contrast. (I was one of 5, had 1; my wife was one of 4, had 2. Typical, in my experience, though I know a couple of contemporaries who had 6 and 7.)

I also remember classmates getting birth control pills in the MID 60s – 64 or 65. Not sure how widely available they were, but college girls were finding them.

You must not have grown up in largely blue collar towns. I lived in 7 at different times.

Generally speaking, the families that had 5+ kids were Catholics. For instance, a Mormon family I knew where the youngest girl was my age (then 10), which meant presumably no more children, had three kids. On my high school debate team, one kid was the only child, one had one sibling, and the one Catholic had two siblings, like me. My mother’s adult friends in Alabama all had 4 children at most, and quite a few had 2 or 3. Oh, and now that I think of it, the one with 4 was also Catholic.

Statista confirms my impression. Average US family size in 1960 was 3.67 v. 3.14 now. The change is nowhere near as dramatic as you suggest, particularly when you consider how many young people are delaying household formation due to being too broke thanks to student debt, and thus having kids much later, which will often mean fewer.

Birth control was harder, but condoms are pretty effective and tracking fertility cycles, moderately effective.

Yes, it was a relatively prosperous neighborhood, mostly Protestant (to my knowledge). What we’d call PMC.

Raising kids, especial young kids, is very expensive and demanding. My wife stopped working when we decided to have our second child because child care was going to eat up over 80% of her take home pay and create all sorts of other complications. And neither of us have family that live nearby; both sets of parents are over an hour away. Giving up her income was a challenge, but believe it or not it makes cutting living expenses easier. One person can devote time to doing that. When everyone’s running crazy between kids, daycare and work you often spend money you wouldn’t otherwise spend – that dinner out or pizza ordered because no one can bring themselves to start dinner at 6:30 at night.

In our friend circle we know multiple couples who’ve done all sorts of things to make things work; and most are like us and don’t have extended family living nearby. We know 2 couples where one spouse works days and the other nights so that child care isn’t needed before and after school. Another couple supplements income by providing child care to other families. We know several couples who’ve decided on mom staying home for the same reasons as us and one couple went so far as to drop down to one car to cut expenses. And I’ve got a cousin who was the better paid earner so her husband stayed home – it’s not just moms anymore and its definitely income (after child care expense) related.

In many of my friend’s cases I would bet things would have worked out differently if wage prospects had been equally different. At least one of our friend couples ended up in the parent staying home not because of choice but because of a lay off. I suspect it became permanent for them in part because doing with less was worth more than going back to the work stress lifestyle.

I’d be more interested in seeing the post 2008 charts.

Cant wait for the day when you can grow children in high tech tanks and society as a whole/state takes responsibility to raise them till university age.

I am though still surprised that people have children after all the post 2008 world revealed about human nature and our societies. Why would anyone want to stress themselves with a massive 20 year liability(on top of others) in a ruthless society like the USA that cant even guarantee clean water or good jobs is beyond me. The USA couldnt even hold a social contract together for a measly 30 years after ww2.

At least part of the sensitivity of Danish women’s child bearing decisions are child care options that are affordable and of high quality. Health care and related costs of child bearing are low or free. In addition men have paternity leave. There is a robust welfare state so schools, and so forth are of good quality.

Much of this was true in states with a strong union presence in the 1960’s to mid 70’s. Since then the way of life described in the 60’s and 70’s and the associated choices and patterns have been destroyed…with Reagan hitting the first hammer blow.