It looks like we were right: online age verification is being used as a Trojan horse for the mass rollout of digital identity systems.

Last Friday (July 25), the Starmer government took a historic step by making age verification checks mandatory for accessing pornography and other supposedly adult content online. The age verification checks can include uploading an ID document — including, presumably, the government’s recently launched digital ID wallet –, checking a person’s age via their credit card provider, bank or mobile phone network operator, or a selfie for validation and analysis.

“It is the biggest step forward in safety since the invention of the internet,” said Labour Party Tech Secretary Peter Kyle. “When it comes to children, that is something we celebrate.”

The Potential Costs of Non-Compliance

While one can argue that restricting children’s access to online pornography is a noble goal, the new rules apply to a bewildering array of websites, platforms and apps, including social media, search engines and even Wikipedia. One estimate suggests that as many as 100,000 services will now have to comply with the rules, or risk ruinous fines of up to £18m or 10% of global turnover, whichever is higher.

The brainchild of successive former Conservative administrations, the new rules form part of the so-called Online Safety Act, which was passed by the Sunak government in 2022 and has since creeped into force in piecemeal fashion. The majority of Labour Party MPs voted against the bill when it was presented. However, since coming to office the Starmer government has not only embraced the Act but expanded its scope by enabling censorship of online speech.

Like the EU’s Digital Services Act, the OSA seeks to compel online platforms “to remove illegal disinformation content if they become aware of it on their services. This includes the removal of illegal, state-sponsored disinformation through the Foreign Interference Offence, forcing companies to take action against a range of state-sponsored disinformation and state-linked interference online.”

The banned content so far has already included politically sensitive news and developments, notes Fred de Fosssard in an op-ed for The Critic:

Footage of British people being arrested in Leeds while protesting against asylum seekers’ hotels was censored on X for users who had not verified their age.

Even worse, videos of a speech made in Parliament by Katie Lam MP detailing the horrors of the rape gangs have also been blocked by these new rules. Speech which has been constitutionally protected from censure since the 1689 Bill of Rights is now being censored online via age verification technology.

It is hard to overstate the significance of this. British people are being forced by the state to verify their age and hand over personal information to view political news about their own country. It is the sort of thing for which British diplomats would castigate third world or tyrannical governments.

Growing Public Opposition

The new law is already deeply unpopular among large segments of the UK public — despite the fact that an estimated eight in 10 Britons supported mandatory age checks to stop young children accessing pornography sites before the new rules came into place, according to a poll by YouGov.

What they probably don’t support is banning children from using Wikipedia to do their homework or blocking access to sensitive political news online. As the FT reports, even a post on X containing YouGov’s own polling on the subject was blocked as it contained “pornography” in the title.

Public support for the measures has already fallen to 69%, says YouGov, though the wording of the survey question has changed slightly from one that specified “pornography websites” only to one that asks about “websites that may contain pornographic material”. If it is anything like Starmer’s public approval, support for the measures will probably have slumped to single figures within a few months.

As of today, more than 465,000 people have signed a petition asking for the OSA to be repealed. Many more are using VPNs to skirt the age checks. So far, one in four Britons (26%) have encountered the new restrictions while browsing, according to YouGov.

As we warned in November, these online age verification checks that are now proliferating across the collective West’s ostensibly liberal democracies threaten to trap everyone, not just minors, in their web. As the Australian government admitted last year, though the age restrictions are only meant to apply to children under 15 or 16, their enforcement requires everyone to verify their age — unless, of course, they use a VPN (more on that shortly):

For governments around the world, one of the great advantages of age verification, or assurance as the Austrian government is now calling it, is that it traps everyone in the same web — not just under-16s but just about anyone who wants to use the Internet. As members of the Australian government recently admitted, everyone will soon have to prove their age to use social media. And that will presumably mean having to use the government’s recently launched digital ID app, myID:

RE: Social Media Ban for Under16's (aka the trojan horse Digital ID for ALL Australians)

So the Federal Labor Gov't have confirmed at Senate Estimates that ALL Australians will have to go through an age verification process to access social media, not just under 16 year olds.… pic.twitter.com/LgPu5DXdek

— Glen Schaefer (@hardenuppete) November 10, 2024

The UK’s Online Safety Act is also hitting hurdles. While the introduction of the age-gating for pornography websites has meant that five million extra online age checks are being carried out per day, according to The Guardian, it has also driven a massive, seemingly sustained surge in demand for virtual private networks, or VPNs. According to some reports, some VPN companies have reported a 1,400 percent increase in sign-ups since the OSA came into force.

Just a few minutes after the Online Safety Act went into effect last night, Proton VPN signups originating in the UK surged by more than 1,400%.

Unlike previous surges, this one is sustained, and is significantly higher than when France lost access to adult content. pic.twitter.com/W9R5FQBWKa

— Proton VPN (@ProtonVPN) July 25, 2025

For readers who don’t know, virtual private networks, or VPNs, are a very standard part of business IT that allow you to connect remote computers together on the same virtual network. As NC reader Balan Aroxdale notes in the comments below, “they are about as common as internet proxies or email”. However, as fellow NC reader Bugs notes, in more recent times “they have become shorthand for services that allow you to appear to have an IP in a different country” (h/t Bugs).

Britons have made use of other creative workarounds. For example, one rather cheeky security consultant revealed on X that it was possible to bypass one age verification tool using a screenshot of Mr Kyle’s own face. From WIRED:

In some cases, reportedly, you can even use the video game Death Stranding’s photo mode to take a selfie of character Sam Porter Bridges and submit it to access age-gated forum content.

For proponents of the law, there is progress to point to as well. The UK’s communications regulator Ofcom says that more than 6,600 porn websites have introduced age checks so far. And major social platforms like Reddit, X, and Bluesky have also added age verification for content that is now restricted in the UK or are in the process of doing so. Microsoft has even started rolling out voluntary age checks for Xbox users in the UK. But even if this movement is satisfactory for now, digital rights advocates point out that normalizing such mechanisms creates the possibility that they will be enforced more aggressively in the future.

“I think people just want to show that we can make some progress on this without thinking about what the consequences of the progress will be,” says Daniel Kahn Gillmor, a senior staff technologist at the American Civil Liberties Union. “We do know that there are some things that you can do to help kids have a better relationship with digital tools. And that involves having an adequate social support network; it involves listening when kids run into problems and making sure that they have functioning emotional relationships with adults who can respond to them. But instead what we’re looking for is a quick technological fix, and those technological fixes have consequences.”

Seema Shah, VP of research and insights at the market intelligence firm Sensor Tower, says five VPN apps have experienced particularly “explosive growth” and reached the top 10 free apps on Apple’s UK App Store by Monday.

The fact that tech-savvy youths are already finding work-arounds while older generations are generally falling into line is hardly a surprise. As we noted in our July 2024 article on Spain’s plans to launch a similar age-verification system for accessing online porn, which even contemplated rationing the amount of porn adult users could access, “if someone specifically wants to continue accessing Spanish-hosted porn, they could do so by simply using a VPN.”

People in the UK, as the VPNs kick in… pic.twitter.com/fxR6WQ6q2b

— Jordan Walker (@JayW132) July 26, 2025

Prior to the launch of the age-checks, the UK government was given fair warning about what would happen. Melanie Dawes, the head of Ofcom, told MPs in May that people would use VPNs to get around the restrictions.

“A very concerted 17-year-old who really wants to use a VPN to access a site they shouldn’t may well be able to,” she said. “Individual users can use VPNs. Nothing in the Act blocks it.”

As VPN use has surged in the past few days, reports have surfaced that the government may try to curtail their use. Such an act would certainly be consistent with its general authoritarian impulses. In a press release published today, it fired off a broadside warning platforms that “they have a clear responsibility to prevent children from bypassing safety protections”:

This includes blocking content that promotes VPNs or other workarounds specifically aimed at young users.

This means that where platforms deliberately target UK children and promote VPN use, they could face enforcement action, including significant financial penalties.

The Register, a British technology news website, predicts that any move against VPN use would likely backfire:

[E}xperts we spoke to were predictably dismissive. One told us that it’s “not gonna happen.”

The government could pull various technical levers, such as banning the sale of VPN kit, but as people who spoke to The Register about the matter said, it would be like banning people from smoking in their own homes.

“You might not like it, but good luck enforcing it,” said Graeme Stewart, head of public sector at Check Point Software. “The logistics are near-impossible. You could, in theory, ban the sale of VPN equipment, or instruct ISPs not to accept VPN traffic. But even then, people will find workarounds. All you’d achieve is pushing VPN use underground, creating a black market for VPN concentrators.

“The only way to do it is badly. You’d effectively be forcing ISPs to block legitimate encrypted traffic and, in doing so, you’d be regulating an entire industry out of existence. Worse still, you’d be legislating against cybersecurity and privacy.”

…

Jake Moore, global cybersecurity advisor at ESET, told us that other methods could see the UK veering into enemy territory, not to mention a PR calamity.

“Although we shouldn’t even consider adopting a route used by China, the Chinese use the technique of analyzing traffic patterns for VPN usage, but this requires expensive infrastructure and constant updates so again, not feasible,” he said.

“Furthermore, many VPNs offer modes to make their traffic look like regular HTTPS anyway, making detection harder yet again.”

To put it in his plainer terms: “Not gonna happen.”

Scott McGready, co-founder of Damn Good Security, agreed that if UK ISPs started snitching on their customers’ VPN usage, it would be “a very worrying position to be in” and the unintended consequences for legitimate users and businesses would be massive…

Morally unconscionable?

Some countries that ban the use of VPNs include Russia, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkmenistan, Myanmar, Belarus, and China. That’s not even an exhaustive list, but it shows the questionable company the UK would keep should it choose to ban VPNs.

A ban not only puts the UK on a concerning trajectory from a privacy and cybersecurity standpoint, but it is also unlikely to work in practice. Possible? Yes, but the practicality of policing such a ban would be challenging.

As shown by individuals in nearly all the aforementioned countries that outlaw VPNs, bans don’t prevent use. People always find ways to circumvent such restrictions, as they do routinely and successfully in more authoritarian countries.

All a UK ban would do is provide the impetus for young people to learn how to circumvent the legislation by using outlawed privacy tech. They would find a way, they always do.

Given the Starmer government is already perceived by voters as “chaotic” while its approval ratings continue to sink to fresh lows, it may think twice before targeting VPNs. That said, the people using VPNs are presumably a minority of the population, and minorities always make for easy targets. At the same time, however, pressure is coming from Washington, which sees the OSA as a bureaucratic nightmare that will punish US companies with huge fines.

Whatever the Starmer government ends up doing, one thing is clear: the Online Safety Act is likely to be manna from heaven for Nigel Farage’s rapidly rising right-wing Reform Party, which is already leading in the polls. Farage has likened the new rules to “state suppression of genuine free speech” and said his party would reverse the regulations.

Well, here's the UK government's response to the petition against the Online Safety Act.

In other news, Reform has already confirmed they will repeal the law if they win the next election.

It's crazy how Labour would give them such a free win. Absolutely brain-dead decision. pic.twitter.com/XrZWJYg4ZH

— Kurt 🏳️🌈 (@KurtJP35) July 28, 2025

For those who don’t have access to X, the government’s Orwellian response reads as follows (emphasis my own):

The Government has no plans to repeal the Online Safety Act, and is working closely with [the communications watchdog] Ofcom to implement the Act as quickly and as effectively as possible to enable UK users to benefit from its protections.

To make matters worse, the UK Secretary of State for Tech Peter Kyle unleashed the following tweet a couple of days ago likening all opponents of the Online Safety Act, in particular Farage, to sexual predators:

If you want to overturn the Online Safety Act you are on the side of predators. It is as simple as that. https://t.co/oVArgFvpcW

— Peter Kyle (@peterkyle) July 29, 2025

This is not to say that a Prime Minister Farage, which is still a distant prospect, would be a genuine defender of freedom of speech. We have already seen in the US how Trump 2.0, after winning re-election by pledging to defend the first amendment, has executed a wide-ranging crackdown on freedom of speech by targeting student protestors, their lawyers and universities, largely for the benefit of Israel. One can expect something similar from Farage, who recently described UK plans to recognise Palestine as “rewarding terrorism.”

But Farage is not alone in criticising the OSA’s age checks. Opponents of age verification mandates include academic researchers, hobby-site operators and digital rights lawyers on both sides of the Atlantic, including the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF).

In a three-part series published on the issue in April, the EFF warned that the mandates “undermine the free expression rights of adults and young people alike, create new barriers to internet access, and put at risk all internet users’ privacy, anonymity, and security”:

We do not think that requiring service providers to verify users’ age is the right approach to protecting people online.

Policy makers frame age verification as a necessary tool to prevent children from accessing content deemed unsuitable, to be able to design online services appropriate for children and teenagers, and to enable minors to participate online in age appropriate ways. Rarely is it acknowledged that age verification undermines the privacy and free expression rights of all users, routinely blocks access to resources that can be life saving, and undermines the development of media literacy. Rare, too, are critical conversations about the specific rights of young users: The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child clearly expresses that minors have rights to freedom of expression and access to information online, as well as the right to privacy. These rights are reflected in the European Charter of Fundamental Rights, which establishes the rights to privacy, data protection and free expression for all European citizens, including children. These rights would be steamrolled by age verification requirements. And rarer still are policy discussions of ways to improve these rights for young people.

This is not at all surprising. The goal here is to radically transform the Internet from a space of relatively unhindered movement into a tightly controlled gated environment. And it is the government and large tech platforms that will hold the keys.

The Trojan Horse of Digital Identity

In recent days, the EU has announced that it, too, will launch an “empowering” age verification system in 2026, with pilots already set to launch in five member states. Non-compliance could lead to fines of up to €18 million or 10% of global turnover — coincidentally, exactly the same figures as the UK’s Online Safety Act. The vehicle by which users will be able to prove their age will be (cue drumroll…) the EU’s recently launched Digital Identity Wallet (EUDIW).

As much as it saddens me to say, it looks like we were right: online age verification is being used as a Trojan horse for the mass rollout of digital identity systems, with all the sweeping threats to basic rights (privacy, security of personal data, freedom of speech, freedom of movement, and with the seemingly inevitable introduction of central bank digital currencies, freedom to transact) that entails. There can be no doubting that protecting the children makes for a seductive pretext.

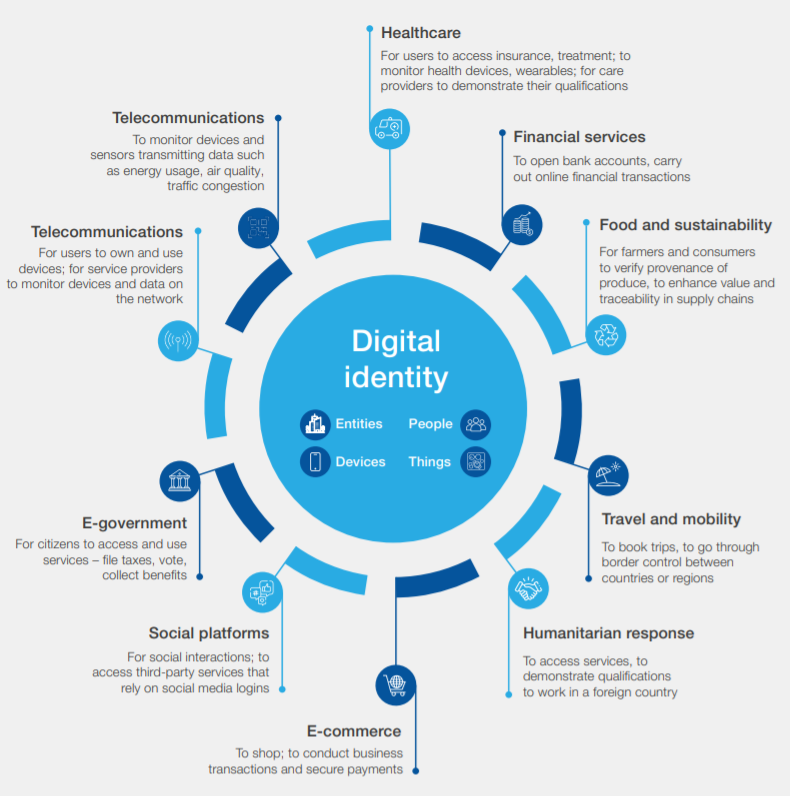

However, the role of digital identity is almost totally absent from the public debate over online age verification currently raging in the UK. And that is almost certainly by design. After all, the ultimate goal is to transform not just the Internet beyond all recognition but just about every aspect of our lives, as shown by the World Economic Forum’s now-infamous 2018 infographic on digital identity.

Lastly, at the risk of leaving readers with a bitter taste in the mouth, here’s Tony Blair, one of the world’s most vocal advocates of digital surveillance and control tech and a major influence on the Starmer government, talking about the inevitable need for digital identity at the recent “Governing in the Age of AI” conference, organised by his own TBI foundation. However, to reach a critical mass, he says, to peals of laughter from the audience, “we will have a little work of persuasion to do.”

Tony Blair on "Digital ID is an essential part of a modern digital infrastructure […] Although, we have a little work of persuasion to do here!" https://t.co/XXGXivHnXv pic.twitter.com/SQ2JwqqexM

— Tim Hinchliffe (@TimHinchliffe) July 9, 2024

Of course, the word Blair was actually thinking of (but didn’t say, for obvious reasons) is “coercion,” not persuasion, since “persuasion” suggests that the people receiving the message will have a choice about whether or not to act on it. That will not be the case here.

Thank you, Nick.

You mention Dame Melanie Dawes, head of OfCom. Her husband Benedict Brogan, formerly of the Torygraph and Lloyd’s Bank, works for Peter Mandelson’s firm Global Counsel. In this instance, Global Counsel is acting for clients who want to restrict free expression.

You also mention Peter Kyle. Kyle is a crony and protege of Blair and Mandelson, friend of Epstein, and funded by the likes of Palantir. His former partner, Ivor Caplin, will soon go on trial for child sex offences, including attempted kidnapping. Kyle used to run an orphanage in Romania, one regularly visited by Caplin.

One does not where to start with Blighty’s corrupt and degenerate elite.

Thanks, Colonel, it truly is a sordid, tangled web they weave.

“Degenerate elite” sound to me as a very apt description of what we have now in Blighty and elsewhere in the CW. It is as if that the most valued aptitude searched for top positions is exactly that: your ability to degenerate and/or bend as much as needed to comply with the “rules based order”.

Or maybe have others bend over for you. :)

“Corrupt and degenerate” is a pretty generic description of most ruling elites. We have to accept it applies equally to the UK.

I believe Luke Kemp’s new book “Goliath’s Curse” covers the rise of such elites as a prelude to collapse, so they do pose an existential threat to the rest of us.

‘Twas ever thus – but the problem in the UK is the level of degenerate pretence of integrity from the centrists and centre/left. We’ve always known about the malign intent of the conservative ruling class, but expected higher standards of conduct from the centre and left, whose socialism always had an element of idealistic ethical crusade.

The continuing disappointment in Starmer and evaporation of his support is partly down to his dissolute character.

It’s easy to see through the US levels of predatory, Mafia like, oligarchic government, but Blairites seek to conceal their self righteousness and justify their moral rectitude.

Both Blair and his Steerpike like lieutenants Mandelson et al, exhibit as powerful levels of self aggrandisement, narcissism and self serving as 47, and that is pretty depressing.

Worse is their continuing mission to destroy what was the Labour Left and dance on their graves, which lingered on in the Labour party up to the 2019 GE, and was self destructive of their own party.

This is all evolving very fast. I recently went to an alternative site (via TOR) and was required to submit to age verification. I am in the good ol’ USA. This limiting of the internet will happen very fast, before the general public knows what’s going on. Thanks Nick for your reporting.

Using Utoob only a few months ago I noticed lots of sidebar suggestions that were AI created. At that point, they were easy to point out. Now, AI is about 1/3 of all Utoob “suggested links”. I predict (in my infinite human wisdom /s) that within a year, AI and other slop will be pervasive across the internet – especially in certain subjects, as it is quickly nearing a majority of music and other arts.

Only well versed tech people or the well to do will have decent (though limited) access to the internet as we used to know it.

You may have had an exit node that went through the UK, or one that was incorrectly flagged as a UK IP. Unless someone decided to treat all known Tor exits as potentially UK in origin, which AFAIK isn’t required by statute (yet) but I could see someone doing it as a CYA measure.

I am hoping this drives more interest in Tor and especially in onion sites (sites fully internal to the Tor network). There hasn’t been much mainstream interest in onion sites recently despite their many advantages, including stronger anonymity (6 Tor hops vs 3 hops for clearnet sites), no possibility of DNS or IP blocking, and the absence of a traditional domain name that can be seized. A few papers, technology sites, and other services offer onion URLs, but interest is much lower than a decade ago and many sites that once provided access via onion URL no longer do so.

Curious to see if Ann Reardon post a video on How to Cook That and her take.

She’s generally savvy on tech and internet but not sure what her politics are.

Technically, she outed herself as not a true Aussie for hating Vegemite so maybe she won’t weigh in.

Of course you have to go into the question of who owns the VPN sites and if they are compromised or not. Are any of them actually honey traps that have a direct feed with some governments? Frankly I would spend the money and go with Kaspersky’s one as after all, what are they going to do with my info? Funny thing, I mentioned to my bank that I was using Kaspersky security and in a letter they wrote back, advised that Kaspersky is not really allowed so much here in Oz and further advised me to go to this government website where I could select a nice honourable one instead. NortonS perhaps? MHAHAHAHAH.

Thanks Rev, I meant to mention this very important point but it slipped my mind. Hat-tip your way.

There seems to be a lot of misconceptions about VPNs here. People seem to think it means a website or business like ProtonVPN. But that’s not correct.

VPNs are a very standard part of business IT. They are simply a means to connect remote computers together on the same virtual network. Support for them is normally inbuilt into operating systems, and hardware network companies will normally provide desktop applications to support VPN setup on their routers.

VPNs are about as common as internet proxies or email. You can’t just “ban” them without breaking the backbone of modern IT systems since the late 1990s. The discourse around this is really appalling.

Thanks, Balan, for the clarification. Have hoisted a few of your words into the post, if you don’t mind.

Well, the same basic technology, but different use cases. I don’t see any way to “ban” use of a VPN as a means to get through a firewall, but that’s not what they are talking about.

Even if they were to ban paid VPN services, shady businesses in other countries are more than willing to provide “free” VPN services in exchange for your data. And of course there is always the roll-your-own approach of renting a $5/month VPS (virtual private server) in another country and installing VPN server software on it. A ban just isn’t realistic short of a Chinese firewall type approach.

I fear that the most likely outcome is for these governments to take an approach similar to how South Korean banks work. Typically they require users to install software that helps “verify” their identity and provide an additional security layer, a holdover from when browsers were less secure. Of course this software isn’t great and has had a number of security flaws, but that’s the rationale. Anyway, if identity-verifying software could be required for accessing something like banking, government services, or social media, and if it could be sourced domestically, many governments (at least Australia and the UK) have legal avenues to compel technical assistance with inserting backdoors via domestic companies.

I think this is the most likely avenue of attack because it doesn’t require leaning on US giants, who have resisted the more extreme demands so far. And it could be accomplished via the private sector with some level of deniability, while providing a nice kickback to the company involved (because neoliberalism).

Note that Twitter/X and pr0n hub, etc., are also locked down in all the EU in response to the Digital Services Act. I follow a few interesting adult performance personalities (self-aware, pithy, mostly lefties, btw) on Twitter and can no longer see their media without changing my location to the USA and pointing my VPN there. I use a VPN that keeps no records, you can look into which one to use on sites that specialize in news about torrenting and international TV streaming. There’s a famous one that is run by Israeli management, so dig around before subscribing. And yes, VPN is part of operating systems and networking technology but it’s become shorthand for services that allow you to appear to have an IP in a different country.

Thanks Bugs, you just earned yourself a wee hat-tip.

<"shorthand for services that allow you to appear to have an IP in a different country."

That, but also prevents man-in-the-middle attack and leaking of destination info, though since widespread adoption of https it isn't quite as necessary. Of course you still need to be concerned about other protocols such as DNS that can leak destination info.

I was in Azerbaijan when they were at war with Armenia and they blocked most commercially available VPNs for the duration. Along with most communication apps. Made it very hard to keep in touch with home.

I hope all websites block access from the UK. That would be the perfect punishment for their stupidity.

The US is not far behind with its SCREEN Act, and many other countries have been rushing to concoct similar restrictions on the internet.

If I may put on my tinfoil hat for a moment, I wonder if this has anything to do with powerful pro-Israel lobbies that have embedded themselves in the governments across the US and Europe that are getting fed up with having freely-available information online that challenges the pro-Israel narrative that is being pushed by most major media platforms? Because of this, this might have caused various pro-censorship sentiments in governments across the world to try and bring the internet to heel once and for all as there have been repeated government and corporate efforts to curtail what people can see and do on the internet since its very inception.

I know that the US technically has the right to free speech in our Constitution but since when has that stopped either party from full-on ignoring our Constitution whenever they feel like it? There are no real legal “teeth” behind Constitutional enforcement at the higher levels of Congress and the Executive branch.

The point is that when things line up with the interests of powerful people and corporations they get done almost instantly, and the opinions of the populace have never mattered to the people really in charge

The extreme censorship that Palestinians have been experiencing for decades (and especially over the past 2 years) is about to become a global standard.