Yves here. It’s been a very long time since I read Samuel Pepys’ diary, so I had a quick look at Wikipedia. Pepys did faithfully record his day-to-day life, including his financial state. As a member of the upper class, he lived well away from the neighborhoods where the plague incidence was high. And perversely, the year when the outbreak was worst was particularly successful for him personally. From Wikipedia:

It was not until June 1665 that the unusual seriousness of the plague became apparent, so Pepys’ activities in the first five months of 1665 were not significantly affected by it. Indeed, Claire Tomalin writes that “the most notable fact about Pepys’ plague year is that to him it was one of the happiest of his life.” In 1665, he worked very hard, and the outcome was that he quadrupled his fortune. In his annual summary on 31 December, he wrote, “I have never lived so merrily (besides that I never got so much) as I have done this plague time.”

So as much as Pepys provided a crisp and detailed account of life in London during a turbulent time (the diary also covers the Great Fire of London), as a top civil servant (an early member of the PMC), he was less exposed to many of its risks.

By Ute Lotz-Heumann, Heiko A. Oberman Professor of Late Medieval and Reformation History, University of Arizona. Originally published at The Conversation

In early April, writer Jen Miller urged New York Times readers to start a coronavirus diary.

“Who knows,” she wrote, “maybe one day your diary will provide a valuable window into this period.”

During a different pandemic, one 17th-century British naval administrator named Samuel Pepys did just that. He fastidiously kept a diary from 1660 to 1669 – a period of time that included a severe outbreak of the bubonic plague in London. Epidemics have always haunted humans, but rarely do we get such a detailed glimpse into one person’s life during a crisis from so long ago.

There were no Zoom meetings, drive-through testing or ventilators in 17th-century London. But Pepys’ diary reveals that there were some striking resemblances in how people responded to the pandemic.

A Creeping Sense of Crisis

For Pepys and the inhabitants of London in 1665, there was no way of knowing whether an outbreak of the plague that occurred in the parish of St. Giles, a poor area outside the city walls, in late 1664 and early 1665 would become an epidemic.

The plague first entered Pepys’ consciousness enough to warrant a diary entry on April 30, 1665: “Great fears of the Sickenesse here in the City,” he wrote, “it being said that two or three houses are already shut up. God preserve us all.”

Pepys continued to live his life normally until the beginning of June, when, for the first time, he saw houses “shut up” – the term his contemporaries used for quarantine – with his own eyes, “marked with a red cross upon the doors, and ‘Lord have mercy upon us’ writ there.” After this, Pepys became increasingly troubled by the outbreak.

He soon observed corpses being taken to their burial in the streets, and a number of his acquaintances died, including his own physician.

By mid-August, he had drawn up his will, writing, “that I shall be in much better state of soul, I hope, if it should please the Lord to call me away this sickly time.” Later that month, he wrote of deserted streets; the pedestrians he encountered were “walking like people that had taken leave of the world.”

Tracking Mortality Counts

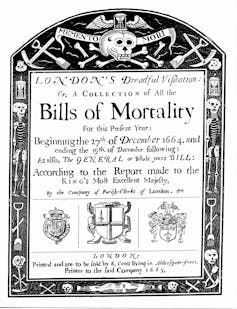

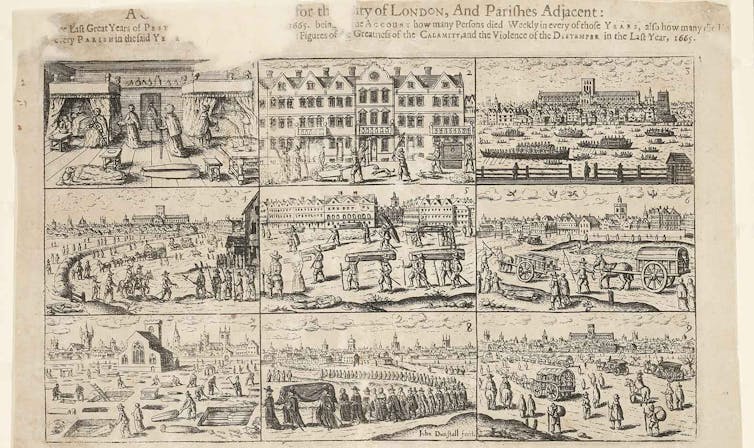

In London, the Company of Parish Clerks printed “bills of mortality,” the weekly tallies of burials.

Because these lists noted London’s burials – not deaths – they undoubtedly undercounted the dead. Just as we follow these numbers closely today, Pepys documented the growing number of plague victims in his diary.

At the end of August, he cited the bill of mortality as having recorded 6,102 victims of the plague, but feared “that the true number of the dead this week is near 10,000,” mostly because the victims among the urban poor weren’t counted. A week later, he noted the official number of 6,978 in one week, “a most dreadfull Number.”

By mid-September, all attempts to control the plague were failing. Quarantines were not being enforced, and people gathered in places like the Royal Exchange. Social distancing, in short, was not happening.

He was equally alarmed by people attending funerals in spite of official orders. Although plague victims were supposed to be interred at night, this system broke down as well, and Pepys griped that burials were taking place “in broad daylight.”

Desperate for Remedies

There are few known effective treatment options for COVID-19. Medical and scientific research need time, but people hit hard by the virus are willing to try anything. Fraudulent treatments, from teas and colloidal silver, to cognac and cow urine, have been floated.

Although Pepys lived during the Scientific Revolution, nobody in the 17th century knew that the Yersinia pestis bacterium carried by fleas caused the plague. Instead, the era’s scientists theorized that the plague was spreading through miasma, or “bad air” created by rotting organic matter and identifiable by its foul smell. Some of the most popular measures to combat the plague involved purifying the air by smoking tobacco or by holding herbs and spices in front of one’s nose.

Tobacco was the first remedy that Pepys sought during the plague outbreak. In early June, seeing shut-up houses “put me into an ill conception of myself and my smell, so that I was forced to buy some roll-tobacco to smell … and chaw.” Later, in July, a noble patroness gave him “a bottle of plague-water” – a medicine made from various herbs. But he wasn’t sure whether any of this was effective. Having participated in a coffeehouse discussion about “the plague growing upon us in this town and remedies against it,” he could only conclude that “some saying one thing, some another.”

During the outbreak, Pepys was also very concerned with his frame of mind; he constantly mentioned that he was trying to be in good spirits. This was not only an attempt to “not let it get to him” – as we might say today – but also informed by the medical theory of the era, which claimed that an imbalance of the so-called humors in the body – blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm – led to disease.

Melancholy – which, according to doctors, resulted from an excess of black bile – could be dangerous to one’s health, so Pepys sought to suppress negative emotions; on Sept. 14, for example, he wrote that hearing about dead friends and acquaintances “doth put me into great apprehensions of melancholy. … But I put off the thoughts of sadness as much as I can.”

Balancing Paranoia and Risk

Humans are social animals and thrive on interaction, so it’s no surprise that so many have found social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic challenging. It can require constant risk assessment: How close is too close? How can we avoid infection and keep our loved ones safe, while also staying sane? What should we do when someone in our house develops a cough?

During the plague, this sort of paranoia also abounded. Pepys found that when he left London and entered other towns, the townspeople became visibly nervous about visitors.

“They are afeared of us that come to them,” he wrote in mid-July, “insomuch that I am troubled at it.”

Pepys succumbed to paranoia himself: In late July, his servant Will suddenly developed a headache. Fearing that his entire house would be shut up if a servant came down with the plague, Pepys mobilized all his other servants to get Will out of the house as quickly as possible. It turned out that Will didn’t have the plague, and he returned the next day.

In early September, Pepys refrained from wearing a wig he bought in an area of London that was a hotspot of the disease, and he wondered whether other people would also fear wearing wigs because they could potentially be made of the hair of plague victims.

And yet he was willing to risk his health to meet certain needs; by early October, he visited his mistress without any regard for the danger: “round about and next door on every side is the plague, but I did not value it but there did what I could con ella.”

Just as people around the world eagerly wait for a falling death toll as a sign of the pandemic letting up, so did Pepys derive hope – and perhaps the impetus to see his mistress – from the first decline in deaths in mid-September. A week later, he noted a substantial decline of more than 1,800.

Let’s hope that, like Pepys, we’ll soon see some light at the end of the tunnel.

Learning about how past generations lived has always fascinated me. To imagine oneself in some distant land or new circumstances, and to see how one could integrate, or not, has been intriguing. Pepys’ time survives for new generations.

Another book that helped me visualize life in a different era was Sixteenth Century Social History, to find out how the average person may have lived and died. Add that to the list along with writings by Eco, Tuchman and many others for whatever era may pique your curiosity. There is some comfort in knowing how people coped, or didn’t, with the daily routines, joys and indignities faced to some extent by all.

Another similarity; they were aware they could catch it from one another. But I wonder if the differences wouldn’t be just as interesting. Also, the removal of his servant Will; was it paranoia or common sense? Or was there any difference in the moment between the two, paranoia and common sense that is? If we knew nothing about COVID-19, except that we could catch it from each other, would keeping a > 30 foot distance be common sense or paranoia? Did they have that precise a list of symptoms that one could judge a headache to be a non issue?

We might say if the probability of success is 51%, it’s goods sense, and 49%, paranoia.

More intuitively, and comprehensibly, we likely say it’s good sense (wrt to that particular social distancing measure) if it’s 99.5% probability catching it being less 30 ft apart, and paranoia if 0.5% avoiding catching it.

Only in hindsight do we, sometimes, or at least not always, know which one it was.

As we in the fog of pandemic war (like struggle), we are not always clear if any preparation, 2 months ahead or not, is good, common sense, or paranoia.

As noted in the article, the plague is a vector borne disease. The Black Plague was transmitted through flea bites.

In the pneumonic form, plague can be spread by coughing or sneezing. Also, infected fleas can jump a considerable distance from person to person, so distancing couldn’t hurt.

While the plague has three forms, the third being septicemic, the Black Plague is believed to be predominately transmitted by flea vector. The Pneumonic form, like the current virus pandemic, is transmitted person to person, but is not believed (little was known about the plagues cause then) to be the primary transmission.

Pepys is well worth the Twitter follow. @samuelpepys

I was just going to add this. It’s a bot that sends out snippets in sequence from “The diaries of Samuel Pepys in real time, 1660-69. Currently tweeting the events of 1667.”

Also read Journal of a Plague Year by Daniel Defoe. It covers the same era.

It’s been a while since I read Pepys or Defoe, but as I recall they asked one of the poor carting away the dead why they did that knowing they would certainly catch the infection. The response was that they might die of the plague tomorrow by moving the dead, but they would certainly die of hunger if they did not. Things haven’t changed that much then.

In 1665 the plague was not a new disease. Europe had experienced this epidemic at earlier times.

The word “Quarantine” comes from the Venetians not allowing boats to dock that had come from plague ports for 40 days “quarante giorno” in the 14th century.

The Great Plague was eventually solved the following year. That was when they had the Great Fire of London on 1666 which burnt down most of the city proper thus ending the plague for all intents and purposes. But by then 100,000 people had died which was a quarter of London’s population at that time. I’m not sure if we could repeat that solution-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Fire_of_London

i think that’s an historical urban legend.

i recall Stephen Fry covering this topic during an episode of QI. just saying

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/QI

I recall reading Pepys displayed grate foresight and priorities, by burying in his back yard, as the flames approached, along with some other treasures, his wheel of Parmesan cheese.

Unlikely the fire had much to do with it. Rats are as capable of avoidance as humans. It was two months after the fire, Nov 1666, before theatres reopened and a service of thanksgiving was held, but Pepys thought it was too soon as people were still dying.

Was it the Great Fire of London (September 1666) that extinguished the Plague (1665)?

That’s one view of History, I have read.

Rev Kev provides a reference above.

Another problem today is the (I’ll take a chance and guess out loud,) increased “fragility” of the supply chain for basics. Is industrialized agriculture ‘better’ than older, more labour intensive agriculture? The effects of artificial fertilizers and pesticides on crop production is also potentially ‘ephemeral.’ A breakdown in the supply chain for those items will have profound impacts on the availability of food. All it would take is a shutting down of a few big artificial fertilizer plants to have a destructive ripple effect through the ‘body politic.’ This pandemic is exposing all sorts of deficiencies in our material and political culture.

Interesting times.

Max Egan talking about The Bigger Picture… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ldp_WrNfz-Y

Re; “Melancholy– which, according to doctors, resulted from an excess of black bile – could be dangerous to one’s health, so Pepys sought to suppress negative emotions; ….”

The bilious MSM, and the Democrat disloyal opposition are briming with Melancholy. Not helpful during this plague, which is tormenting our World.

[Aside] – Pepys on Shakespeare.

“Saw Midsummer Night’s Dream which I have never seen before, nor shall ever again, for it is the most insipid, ridiculous play that I ever saw in my life. There was, I confess, some good dancing and some handsome women, but that was all of my pleasure.” (29 September 1662)

“Saw Twelfth Night acted well, though it be but a silly play and not relating at all to the name or day” (6 January 1663)

“Though I went with the resolution to like [Henry VIII], it’s so simple a thing, made up of a great many patches…that there is nothing in the work.” (1 January 1664)

He was admiring “handsome women”? I thought all actors were male in Shakespeare’s time.

He meant in the audience. Even in church he looked for women – and on one occasion, trying a grope, was threatened with a hatpin.

Dead right about Midsummer Night’s Dream.

A book: Kristin Lavransdatter (by Sigrid Undsett, Nobel Literature Prize, 1928):

Fictional biography of a woman in Norway in the 14th century. In the last chapter, she dies of what everybody died of in 1348: plague.

Interestingly: in the book, people dealing with patients affected by the disease covered their own nose & mouth with a cloth soaked in vinegar; and that seemed to prevent some of the contagion, (although Kristin dies anyway).

At around the same time the village of Eyam in Derbyshire became the village of the damned, going into self-quarantine to save others :

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-35064071

Newton went into seclusion on his estate. He used the couple of years to good use in getting quiet time to make major advancements in math and physics.The whole process took almost 20 years, but a couple of years in seclusion with little interruption helped consolidate many thoughts: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-truth-about-isaac-newtons-productive-plague

By the time Newton was done, the world and solar system had a mathematical explanation. Faraday and Mawell advanced that greatly 200 years later setting the stage for Einstein a few decades later.