Yves here. Even with Covid-19 shaking the economy top to bottom, some trends grind on. For instance, automation is a fetish even when the payoff is questionable. Readers discussed how WalMart intends to eliminate cashiers and replace them with automated checkout, which seems idiotic based on how well they work at CVS (not). I see the cashier have to run over to Do Something to help a customer complete a self-checkout sale at least one time out of three. Moreover, self-checkout promotes theft; the last stats I saw (and I’d be curious to hear if retailers have figured out new counter-stategies) is that shrinkage is about 1% higher in stores with self checkout than not.

I like the authors’ theory of how automation affects employment, but I am much less taken with their claims about offshoring. For one, a lot of jobs offshored are not ones that have been unbundled; a call center worker in India performs the same tasks as ones in the US.

And while we are on the subject of call center workers, my limited sample suggests, depressingly, that companies are using coronavirus as an excuse to degrade customer service even further by shifting more to know-nothing offshored phone reps. It’s particularly offensive to see Cigna pulling this stunt when health insurers are making out well from the coronacrisis.

By Ester Faia, Professor and Chair in Monetary and Fiscal Policy, Goethe University Frankfurt; Sébastien Laffitte, PhD candidate, University Paris-Saclay and CREST; Maximilian Mayer, PhD student, Goethe University Frankfurt; and Gianmarco Ottaviano, Professor of Economics, Bocconi University; and CEPR Research Fellow. Originally published at VoxEU

Understanding the effects of automation and offshoring on labour markets and growth has been a significant topic of interest. This column argues that automation and offshoring fundamentally affect the matching between firms and workers and do so in contrasting ways. It predicts that automation will increase firms’ and workers’ job selectivity and decrease employment, while offshoring will have the opposite effect. Empirical evidence as well as a quantitative model support this hypothesis and provide a mechanism of technological change typically missed in standard neoclassical reasoning.

Automation and offshoring are two contemporary trends that are perceived to have a disruptive impact on several aspects of the labour market, such as employment opportunities or wage inequality, and growth. Understanding their effects, their relative importance, and their possible interactions has been the focus of many influential papers (among many others Acemoglu and Restrepo 2020, Autor et al. 2013).

If we think of automation and offshoring as simply two different types of `technological change’, standard neoclassical reasoning suggests that their effects will not be different from those of previous industrial revolutions. Any improvement in the state of technology leads to an increase in labour productivity. In turn, employment increases as labour demand cannot deviate from the long-run path dictated by the evolution of labour productivity. Concerns about the impact of new technologies can be rationalised only if one departs from the neoclassical paradigm in which any threat to wages and employment may come more from the impacts on the competitiveness of markets in the presence of frictions rather than from changes in the production function in the presence of frictionless markets (Caselli and Manning 2019).

In Faia et al. (2020) we hypothesise that beyond productivity effects, automation and offshoring fundamentally affects the matching between workers and firms. Firms need workers with heterogeneous skills to perform heterogeneous tasks. A match occurs when a firm meets and employs a worker with the appropriate skills. The ideal match delivers the maximum achievable productivity. The productivity of less-than-ideal matches decreases with the distance between the matched tasks (on the firm side) and skills (on the worker side). Matches between firms and workers are not necessarily ideal as search frictions make them less selective, i.e. willing to accept less-than-ideal matches. This is how search frictions induce ‘mismatch’ between tasks and skills, that is, divergence between the actual matches and the ideal ones.

Our key hypothesis is that better matches (i.e. matches that generate larger outputs for a given firm-worker pair) enjoy a comparative advantage in exploiting automation and a comparative disadvantage in exploiting offshoring. As such, automation will increase firms’ and workers’ selectivity, which in turn decreases mismatch and employment. Following the same logic, we predict that offshoring will increase employment by reducing selectivity.

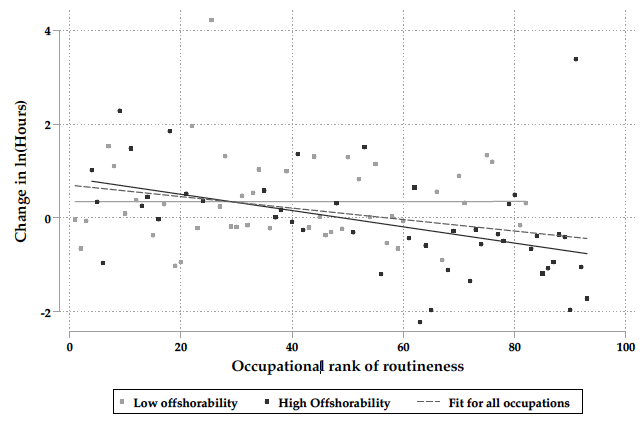

Figure 1 gives a first indication on the interaction of automation and offshoring and their effect on employment using data from the European Labour Force Survey for 13 European countries. Occupations that had a higher probability of being automated (as measured by their routineness) in 1995 experienced a decrease (dashed line) in total hours worked in the subsequent years (1995-2010) as employment shifted from routine to non-routine occupations. This negative relationship is driven by highly offshorable occupations (solid black line), while the change in hours worked seems unrelated to the routine-intensity in low-offshorability occupations (solid grey line).

Figure 1 Automation, offshoring, and hours worked

The idea that automation increases the value of the ideal match by making skills and tasks more complementary is motivated by recent survey evidence (2018 Talent Shortage Survey by Manpower Group, 2018). This evidence highlights the increased prevalence of talent shortage with a growing number of jobs left unfilled because applicants are not talented enough for the job. Talent shortage is strongly linked to technology, but does not necessarily depend on a dearth of workers with higher education. Difficulties in recruiting the ‘right man for the job’ tend to be reported in manufacturing, ICT, and health care for jobs such as skilled trades workers, machine operators, sales representatives, engineers, technicians, ICT professionals, and office support staff (Cedefop Eurofound 2018). Machine operators, for instance, are required to have machine-specific experience ranging from the knowledge of production procedures to the ability to understand blueprints, schematics, and manuals. Due to technological change, they are also increasingly required to be familiar with different types of machines, each with its own specific blueprints, schematics, and manuals. A concern for both firms and workers is that retraining from a known to a new machine can be a costly time-consuming process, making them cautious about a potential mismatch.

If automation increases the productivity of ideal matches relative to less-than-ideal ones, it may, therefore, make firms and workers more willing to give up the surplus of a less-than-ideal match and instead wait for a better one. This increased selectivity improves the productive efficiency of matches that are eventually formed and better matches end up commanding a higher wage premium. The result is increased match efficiency together with more unemployment and wage inequality. The type of heterogeneity we have in mind is ‘horizontal’ rather than ‘vertical’ as usually assumed in the literature on skill-biased or routine-biased technological change. While these concepts are very relevant, our paper highlights additional effects of automation and offshoring at work independently from any vertical heterogeneity. As ideal matches are the ones that define firms’ and workers’ core competencies, we use ‘core-biased technological change’ to label the way technology evolves in our conceptual framework.

Differently, offshoring may increase the productivity of less-than-ideal matches relative to ideal ones by allowing firms to unbundle tasks into subtasks to be performed at home or abroad depending on comparative advantages. It may, therefore, make firms and home workers less selective. On the one hand, decreased selectivity reduces the productivity of ‘less-than-ideal’ matches that are eventually formed. On the other hand, match surplus may still increase thanks to specialisation according to comparative advantage. Hence, differently from automation, offshoring may lead not only to higher match productivity, but also to higher employment and less wage inequality.

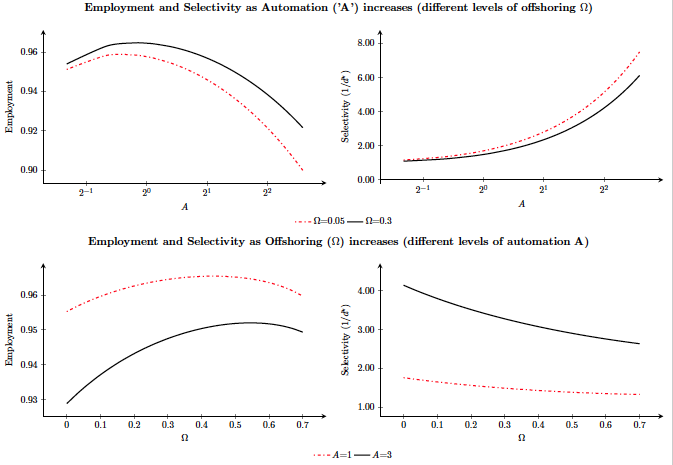

When embedded in a quantitative model, these features imply that how automation and offshoring affect labour market outcomes depends on the interactions of four effects. Figure 2 displays simulation results of our model where higher automation (A) implies productivity increases due to more automation and higher Ω corresponds to the share of production that is offshored. While automation increases the productivity of any given match (‘productivity effect’), it also increases the relative productivity of ideal matches relative to less-than-ideal ones (‘mismatch effect’). In parallel, offshoring increases the productivity of any given match thanks to domestic workers’ subtask specialisation (‘specialisation effect’), while also decreasing the subset of subtasks assigned to them (‘substitution effect’). As productivity and specialisation effects of automation and offshoring increase the match surplus of domestic firms and workers, mismatch and substitution effects work in the opposite direction. These opposing forces create an inverted U-shaped function of employment in automation and offshoring: productivity and specialisation effects dominate when automation and offshoring are limited whereas mismatch and substitution effects dominate when automation and offshoring have already reached an advanced stage.

Whether our theoretical mechanism indeed operates in practice (i.e. whether the mismatch effect is strong enough to reverse the neoclassical conclusions) is in the end an empirical issue, which we investigate focusing on 92 occupations at the three-digit ISCO-88 level and 16 (out of 21) sectors according to the NACE Rev.2 classification from 13 European countries for the period 1995 – 2010.

Figure 2 Automation, offshoring, and employment (quantitative model)

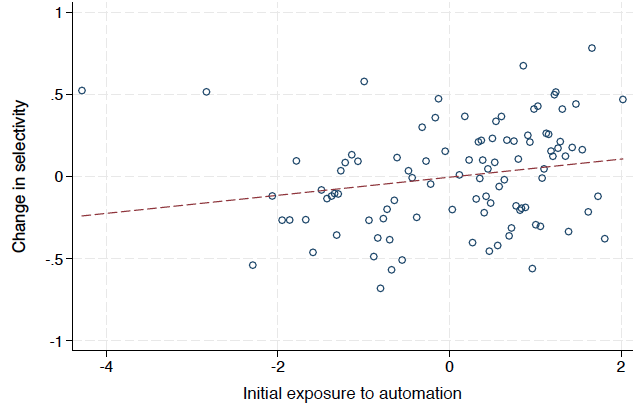

We capture firms’ and workers’ match selectivity at the sector-occupation level. While a sector may cover a rich menu of occupations, these include a submenu of ‘core’ occupations that are disproportionately concentrated in the sector. In this respect, an increase in the concentration of occupations’ employment across sectors can be interpreted as an increase in match selectivity. We thus compute an index of selectivity (the ‘sectoral selectivity of occupations’) defined as the concentration of occupations’ employment across sectors. The index inversely measures the willingness of firms and workers to accept less-than-ideal matches. Figure 3 shows that selectivity rises in our sample period especially in occupations that are highly automatable.

Figure 3 Automation and selectivity

This suggestive evidence is confirmed in our econometric analysis. In line with our model we find that occupations with higher automatability become more selective. This effect is driven by occupations with above-median automatability while there is no impact on selectivity for occupations characterised by below-median automatability. We also find that sectors with higher initial offshorability experience a differential decrease in selectivity. Our results continue to hold when we use more standard selectivity measures borrowed from the literature, such as ‘skill mismatch’ and ‘unemployment duration’.

As our model predicts, we find a robust negative relationship between selectivity and employment at the occupation level. To address potential endogeneity concerns stemming from the fact that our measure of selectivity is calculated from occupation employment shares, we construct a Bartik instrument. The negative effect of selectivity on employment materialises especially in occupations with above-median automatability. Finally, by putting together the results on the impacts of automatability and offshorability on selectivity with those on the impact of selectivity on employment, we show that automation reduces (offshoring increases) employment through the selectivity channel of our framework.

Growing concerns about the negative impacts of automation and offshoring on employment and wage inequality are well documented. While traditional neoclassical arguments imply that those concerns are unfounded, a negative relation of employment and wage equality with improvements in technology arises naturally in our setting of ‘horizontal mismatch’ where search frictions hinder the efficient assortative matching between firms with heterogeneous tasks and workers with heterogeneous skills. Our analysis in terms of ‘core-biased’ change illustrates a more general idea of how wages and jobs in frictional labour markets may react to shocks beyond our application to technology and offshoring.

See original post for references

I’ve rarely had a problem with self checkout. My guess would be less than 5% of the time. I rarely see the store staff have to help someone else out. The problems I’ve had is when the bar code doesn’t scan or there is no bar code.

As to the 1% increase in shrinkage, what is the cost saving of the self checkout machines? Seems hard to believe that it is more than 1%. But I don’t have any data.

I have only seen self checkout at CVS (multiple stores, always problems) and in two grocery chains where I was in each store only a few times, but again I saw cashiers having to assist regularly. My sample suggests the difficulties are more extensive than you think.

I agree, CVS seems to struggle with self checkout. I think this is something that scales though. Our walmart in DC has self check out and its pretty efficient. 8 machines. 4 on each side of a wide row. An employee (or 2) stationed at the end of the row to help those who need. Also, video camera and TV above each machine showing customer to limit shrinkage

It sounds to me like the problem where you are is unfamiliarity with the process. As well, later posts in this thread seem to indicate poorly designed self checkout software.

Here almost every major store has self-checkout as an option all day, and it is the only way to check out the rest of the day (often 2300 to 0800, approximately).

There is a person somewhere in the store who can deal with exceptions, but they are rarely called. I’d guess that issues not automatically dealt with by the software arise in 1 or 2 percent of cases.

I can only recall one instance of store staff being needed in the last few months while I was nearby, checking out. Most stores have between 4 and 16 self-checkout stations, usually in clusters of four.

These checkouts are common, almost ubiquitous, in supermarkets, department stores, hardware and building supply stores, (larger) pharmacies, and in a slightly different form, all gas stations, at least for fuel.

The software is surprisingly good, and glitches that tended to arise five years ago are rarely seen.

As a bonus, queuing is substantially improved over most common implementations of the not self checkout option.

>>> It sounds to me like the problem where you are is unfamiliarity with the process.

Yay, it’s the customer’s fault for not knowing how to use the store’s equipment correctly.

>>> As well, later posts in this thread seem to indicate poorly designed self checkout software.

Software caprification is not an excuse for bad product design. And this is usually the go-to excuse were here from tech-utopians. In my experience, poor software is usually the results of poor management rushing development, cutting budgets, arbitrary cut-offs and deadlines. Generally, it’s a poor understanding of what software can and cannot do.

But I still have to call you out on the “bad software” defense as most of the problems described here are NOT software issues. Is a higher tendency for theft and shop lifting a software issue?

At a Walmart, I saw a woman in her 80’s just struggling to move the merchandise across the scanner. So, the helper basically had to do it FOR her – just like a check out person. But only less efficient because the helper had to server as both check out person and bagger. Even if another employer was available to help, there is only room for one person. And meanwhile, he was unviable to help out the second station that also had issues (what are the odds.) and simply had to wait. The other two were off line. The “helper” clearly didn’t have the ability to get these systems up and running. (More software issues.) We waited for 40 minutes. In the end, the manager finely put two standards check out stations on line and clear out the backlog in 20 minutes.

Self-check-out works fine – until it doesn’t, and has to be bailed out using more traditional methods. This is one example of where self-check-out had to be bailed out using conventional cashiers. So no, they are clearly not more efficient than conventional check out.

The real problem with self-check-out is that it depends on everything goring perfectly. But this just isn’t reality. Things always go wrong. And if you can not deal with minor issues quickly, they always escalate into a major problem. And the nature of self-check-out means that when inevitable problems do happen, there is virtually no mechanism in place to deal with the issue. So defenders are left with the only recourse available to them, blame the consumer.

+1, geez louise…

“But I still have to call you out on the “bad software” defense as most of the problems described here are NOT software issues. Is a higher tendency for theft and shop lifting a software issue? ”

Depending on how it is done, it certainly can be.

A well implemented self checkout is easy to use, operationally robust, and incorporates checks to detect common hard to see forms of fraud or theft.

Shoplifting is not inherently connected with self checkout. Increases in shoplifting are quite likely due to lower staffing levels, rather than self checkout directly, and a cashier at the front of the store busy with a line of customers can’t do much about the shoplifter at the back of the store sticking things in her pocket, backpack, or purse.

Well designed self checkout systems cope with the most common problems quite well. One example cited in a post here was an item with no product code. In my experience this happens with fruits, vegetables, and bulk food items.

Rather than locking up, a good self checkout system will offer a ‘no code’ option that takes the shopper to a description tree, usually with several choices per level. In 3 or 4 simple choices the item is identified and checked out appropriately (weighed or counted by shopper).

A typical description tree I have used may look like

Type/category of item

(press) Fruit

Kind of fruit

(press) Apple

Kind of Apple

(press) Spartan

At that point the item is uniquely identified and can be processed normally.

Note that missing or damaged UPC codes are a different class of problem, less likely and handled in a different way. Products with UPC codes make up the overwhelming majority of products in most major stores.

What self checkouts cannot handle are products like alcohol, or tobacco which have legal age restrictions, and certain drugs and other pharmacy products that are controlled or considered dangerous without access to professional advice. The sections of the store that contain such things are typically blocked off by locking individual shelves, shuttering shelving units, cordoning off aisles, or relegating them to a locked ‘behind the counter’ location.

Please note that I did not ‘blame the consumer’. There is no blame attached to unavoidable ignorance due to lack of experience with something new. It is an issue to be understood, and mitigated in various ways, but not a cause for blame. Many stores have significant numbers of staff in constant attendance at new self checkout installations for a period of weeks or months, until customers become familiar with the process.

In the stores I use there is always someone available to help if there is an problem, usually in an obvious location no more than ten or so metres away, and they generally respond quite promptly.

I don’t see how software can stop the simple swipe fraud of stacking two items on top of each other (better yet identical and not too fat, a frozen pizza would be ideal), scanning the bottom one only and bagging both. A camera might catch that but that requires human review. Or how about not scanning something in the cart and loading groceries into the cart so as to cover the item you “forgot” to scan?

You don’t know my nearby CVS. With its crappy self-checkout, there is also often no one at checkout either.

>The problems I’ve had is when the bar code doesn’t scan or there is no bar code.

Well duh. That’s pretty much checkout, what other problem did you expect? And what happens then:

1) You hit a button to light a little light

2) They you stand there, hopefully some employee doing something else at least gives you an “I’ll be coming over shortly” wave.

3) They finally show up

4) They listen to your explanation of the problem.

5) They try to do it themselves. They don’t think you are an idiot, but sometimes that works

6) They then hit the PA system and call for a “price check”

In contrast, in a regular line, the cashier swipes it, looks at it, swipes it again, and calls for a price check.

See the difference?

Now, I actually agree with your second point, the Masters Of Society will tolerate a loss up to the cost (and probably then some) of employing staff if it means not having to hire actual human beings. Plus they get to throw people in jail when said customers do get caught, so there’s the entertainment bonus for psychopaths.

My experience is that they come over in a ….reasonable…. amount of time..

They understand the problem very quickly. Sometimes they get it to work when they try, sometimes they don’t and then they type in the correct code.

Only once this year have they asked for a price check and I said no thanks and passed on buying that item as that’s when the wait becomes unreasonable.

I’m with you and don’t believe the country’s largest retailer would be pushing this change if they didn’t think it worked for them despite greater “shrinkage.” It should be said though that the story linked yesterday said that Walmart was only trying full self-check at one of their stores as an experiment. And as I noted yesterday they are also all in with online order for grocery pickup (doubtless growing even more popular during Covid) and our one local Walmart grocery is now full of people with blue carts pulling orders off the shelves. It’s quite possible that the total number of workers inside the store hasn’t changed at all despite the heavy self-check presence (typically only one human cashier) at this store.

I’d say the real crisis in retail employment is less this limited push to automation and more worries about whether brick and mortar stores will stay open at all. Amazon is the elephant in this particular room.

I work at a grocery store with an automated cashier. The machine screws up all the time. They get coins jammed in the hopper that feeds the machine coins, the paper jams, if someone decides to move groceries on the scale it screws up, and once it starts to act up with a customer it will continually do so for the rest of the transaction. When I work at the auto-teller my job is to wait patiently besides these stupid machines and help customers navigate through the experience. No one likes the machines at work.

Since I use self-checkout all the time I’d say some systems are a lot better designed than others.

I used to use the self-checkout lanes fairly regularly at the local Super-Valu chain, and there they are a nightmare. I have wondered if they can/do adjust the settings on them to prevent shoplifting. In particular, anything that the system thinks doesn’t belong in the bagging area, including my own reusable bags, will shut the system down. In addition, anything the system assumes should be in the bagging area, and isn’t, will also shut the system down. And then there are the items not programmed into the system, the scales that don’t work properly, the items that mis-read. Even before COVID hit I’d given up on them for more than two or three items because they just became too exhausting to use for larger purchases. Now I can’t believe anyone would want to use them, at least not without gloves.

One place I notice that does not use self-checkout and also has freaky-fast cashiers is Aldi. It seems to me that something could be learned there.

The ONLY time I need human assistance at a Walmart self-checkout is when I buy alcohol.

Now I usually try to use a human checker but there’s no denying that automated checkouts work well – at least in my case.

The ethical problem is that automation is not and has not been financed ethically – thus cheating the workers it displaces.

And that’s a problem with MMT proposals – they do not address the ethics of the current Gold Standard based banking model but only its stability. As if injustice should be made more stable!

Quoting an economist : “Since the dawn of the industrial age, a recurrent fear has been that technological change will spawn mass unemployment. Neoclassical economists predicted that this would not happen, because people would find other jobs, albeit possibly after a long period of painful adjustment. By and large, that prediction has proven to be correct.”

As I recall correctly, if you look at the time in UK when automation first appeared, it took about a generation for the increase in employment due to automation to take place. That likely applied to each area of automation that caused unemployment.

Now that automation is happening faster and reaching into new areas that had been considered safter before?

The start of the Industrial Revolution in England was even worse for workers than you intimate. Studies have found that living standards fell for at least one generation and some argue two.

And it would have been worse and/or longer if nobody had left the UK for American where wages were higher and land was plentiful and cheap.

Yes the Industrial Revolution was so popular in the UK, that the Yoemen flocked to the factories.

Except for the series of Enclosures Acts designed to force the Yowmen off the Commons.

And This:

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen?

And did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Bring me my bow of burning gold!

Bring me my arrows of desire!

Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire!

I will not cease from mental fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand,

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England’s green and pleasant land.

William Blake

I don’t know a about the short term effects, but after two centuries and in the wake of COVID, the nature of the “adjustment” seems apparent. An idle hired hand being the commie pinko devil’s workshop, automation has created a plethora of non-essential and bullscat jobs.

Was there a bullscat control variable in this VoxEU model? l couldn’t find one.

Yeah economists always pull long, thoughtful faces and gently admonish us that any given neo-classical “prediction has been proven correct”.

And if you show them facts that prove otherwise, they will ignore them.

” if one departs from the neoclassical paradigm in which any threat to wages and employment may come more from the impacts on the competitiveness of markets in the presence of frictions rather than from changes in the production function in the presence of frictionless markets (Caselli and Manning 2019).”

What defines the market as competitive? – Also, what is interacting to cause frictions? and what is decoupled to remove friction?

Define the ‘market’ as well please – It seems to me that “the market” that you describe is a market for tangible products, if that is so, then any mismatch between worker and employer and its use of automation is a mismatch caused by management in the company and the only frictions, drag or molasses is coming from area costs- like -cost of living and doing business -rent-finance-insurance-tax housing those things that add to cost of production but are not part of production, you know – the costs which are outside the company but must be paid to the labor in order for the labor to survive let alone any premium for a match.

100% of people at any level in a company are geniuses and brilliant (they might not know at what) and are capable of almost any task or acquisition and learning thereof – unfortunately, there is a group sharing the same attributes but who lack vision, ethic or may have had their spirit crushed in this world, or otherwise have simply walked or been pushed off track through no fault of their own – in any event – they are the earners of unearned income that the tax system has made the easiest way to make big bucks –

It is the companies job to address the 100% to bring out and reward the geniuses and the brilliance in their fellow humans – I have never seen a mismatch on the labor side of things – in the management side – yes – and at the board level….most all the time but, it’s not because of the individual but the environment in which that individual is supposed to play by the rules of the speculators and the FIRE sector who have so warped the tax code and the regulations and subverted the system to such a degree that, the only way to most easily earn money (we all want that) is to game the system

I leave a quote below

“The great sore spot in our modern commercial life is found on the speculative side. Under present laws, which foster and encourage speculation, business life is largely a gamble, and to “get something for nothing” is too often considered the keynote to “success”. The great fortunes of today are nearly all speculative fortunes; and the ambitious young man just starting out in life thinks far less of producing or rendering service than he does of “putting it over” on the other fellow. This may seem a broad statement to some: but thirty years of business life in the heart of American commercial activity convinces me that it is absolutely true.

If, however, the speculative incentive in modern commercial life were eliminated, and no man could become rich or successful unless he gave “value received” and rendered service for service, then indeed a profound change would have been brought in our whole commercial system, and it would be a change which no honest man would regret.- John Moody, Wall Street Publisher, and President of Moody’s Investors’ Service. Dated 1924

Economists and their reasoning….

This bit:

Offshoring increases employment? Probably true in a global sense but employment, like politics, is more of a local concern.

Another quote from above:

Automation leverages the skill of the worker -> A skilled worker can produce a lot more value than an unskilled worker – what else is new?

The difference in output between a 25% match and a 50% match isn’t necessarily the same as the difference between a 50% match and a 75% match. The difference between 75% match and 90% match might not be worth not hiring especially if the 75% match can in time (through on the job training/learning) improve the match to 90%. Companies are now (often in my opinion) willing to wait for the best match while workers are (again in my opinion) willing to take a chance.

The ‘wage-premium’ is probably mostly related to bargaining position. Due to anti-hiring policies the few candidates that make it through the anti-hiring process can bargain for higher wages.

And this bit:

Is it implied that the unbundling of tasks can only be done when offshoring?

If the unbundling of tasks is done correctly then a subtask might be possible to automate or to offshore. If the unbundling is done incorrectly then the results will be poor

Sometimes good ideas are completely undone by poor execution. Automation and off-shoring can have common causes for failure and in my opinion then a common cause is poor planning. The automated check-outs might be one example of poor unbundling of tasks. Or possibly not, maybe the tasks that the automated check-out doesn’t do were seen as too costly so therefore those tasks aren’t done any longer.

Managers and executives get rewarded for projects of automation and off-shoring, the outcome of the projects is not very important the important bit is that they attempted it. Firms might lose out but managers and executives win out, either due to success of the project or as a learning experience of having managed a (failed) project.

If one is to take a cynical view of offshoring call centers the reason health insurance love is this because their profit motive is to delay, dispute, and deny any and all claims. This way more money can be made on the float. And some folks will just get frustrated to the point of giving up. What better way to do this than to contract for a call center that has operators for whom English is a third language at best?

This is a feature not a bug.

Even cynicism isn’t what it once was. They don’t even try to hide things as well. One clear goal of call centers is to make the customer acknowledge their end of the power relationship, even as those hapless center people try to eke out a living. Win-win for the insurer.

‘horizontal mismatch’ where search frictions hinder the efficient assortative matching between firms with heterogeneous tasks and workers with heterogeneous skills

Augh! Good grief! my eyeballs hurt now from ricocheting off this prose again and again.

And Bog help me, I still don’t have a clue what the real world takeaway is here, for a manager, policymaker or skilled trade. As a former boss liked to ask me when I bloviated on too long: So where’s the effing pony?

Haven’t we long established here that ‘talent shortage’ is at bottom Corp weaselspeak for firms being unwilling to pay suitable wages? Or to provide other conditions that retain a pool of experienced, reliable techs with superior problem-solving skills? e.g. job stability, being part of a great engineering culture(ht Stoller), etc.

And don’t automating companies today nearly always contract O&M out to the OEM (or installer), at least during the warranty period? Hint: yes. Or did the Suits already blow their rosy value case on the installation (and are maybe suing the OEM after exhausting LDs)? and are now hastily trying to self-perform, using a revolving door of under-30 non-union trades (Dilbert: “We like them bright but clueless”)

But I suppose it’s pointless to try to define ‘automation’ in any tangible sense here. Not when the authors are defining ‘selectivity’ as ‘the concentration of occupations’ employment across sectors.’ Up through the atmosphere….

Anyway, my apologies for pounding the nail through the board. Just venting. I think Marshall Auerback wrote something here on this very important topic a while back. I’ll try to dig up a link to make it more constructive.

Funny how corporations are responsible for our health care but not for our education. Seems backwards.

Not funny or surprising though when you realize the first keeps us held by “the short and curlies” and the second would actually be helpful.

“Greatest place in the world to start a business” — yeah, if your spouse has heathcare… If not, then please do not apply.

I am not an economist, but I am impressed by Dean Baker’s (cepr.net) argument that if lots of jobs have been lost to automation over the last two decades, we should have seen lots of increase in productivity. He says we have not. Is he wrong?

Looking at the wrong type of productivity. Need to look at the capital piece instead of labor. That is where there has been some, er, fantastic productivity. Look at a few select publications like, say, The Robb Report, to see what one’s billions may entitle one to, besides grammar.

unthinkable a month ago, Senate could go to D’s https://www.agri-pulse.com/articles/13903-gops-farm-state-senate-seats-increasingly-at-risk-with-majority-at-stake

You are not going to learn anything about running a small business, the economic foundation, by studying warmongers, and you are not going to learn anything about macroeconomics – the NPV window, short of raising your own children. I can’t help you with the latter, but there are a few things you need to know about the warmongers to avoid their traps.

1) They have always been at war. It’s all they know. They are frightened when they are not at war, and when you are not at war. They are hard-wired, with overlapping social brain waves.

2) They must get you to compete for MMT, to validate their own “privilege” and keep you occupied where it matters – your mind.

3) They still have to get someone to do the work. There are libraries on the psychology of how to manipulate the way people think about working people.

4) The landlord is the employer and the employer is the landlord. They squeeze from both directions. That’s accounting.

Ever wonder why your supervisor asks you when you are going to buy a house? Ever consider how many times the Boeing merry-go-round has bought and sold the same homes in Seattle? Ever wonder why educating your children is their imperative, leaving you to pay the bills? In consideration of NPV, why would you go to work so someone else can raise your children? Why are the warmongers so determined to dilute your DNA and immune system response?

Someone has to fix that automation, and it’s not going to be them.

re: automated checkout

I have lived in Portugal for several years, and the larger supermarkets all feature automated sections, along with more traditional manned stations. Typically, there is a person assigned specifically to the automated sections (usually six machines), and there are no problems to speak of. Clearly smaller stores such as CVS would not be able to warrant paying a dedicated person to watch the automated machines, but there is no reason why any larger store should be unable to do so.

“walmart eliminate all cashiers”

i had warned of this when the wage was raised to $12 (or is it 15 now) at walmart. We could not find employees at $10 anymore (we cannot pay any more, but that’s because the subsidy that sustains us has not been raised since 1999, and we have to maintain customer/employee ratios by law).

large retail does not care anymore whether customer likes the “experience” or not.

they want your money, and they know you have nowhere else to go.

capitalism will destroy itself and the rest of us, before it shares the cake.

A local grocery store here in Seattle called PCC used to have self-checkout kiosks, but removed them all last year. At the time they said they did it to foster community, if I am remembering correctly, but several of the checkers I discussed it with all told me that it was efficiency-related. They could move the customers through far faster than kiosks in their generally cramped and busy stores.

There are so many non-automation job opportunities staring us in the face that it is ridiculous. But this assumes that the Federal government exists to actually IMPROVE our country for the benefit of it’s citizens. That is a fatally BAD assumption, our country currently is lead so that the oligarchs can RAPE the citizens with impunity.

Starting a jobs program similar to the CCC that puts a million people into our national forests to just clean them up and reduce the fire hazard would be a very good thing. Very little to no skills required, and automation cannot handle this job – too complicated, but good old humans can just “get er done”. Trump even mentioned that “raking the forest” would have helped prevent the Paradise Fire in CA. (I doubt that, PG&E just quit doing real maintenance and throwing the CEO on jail forever would be a better solution for that because then CEOs might want to actually MAINTAIN things.) Certainly, having low skilled people available for the Forest Service to direct for brute force projects would a benefit to them, an opportunity for the unemployed, and provide a very valuable result for us all.

If you get into the trade young and invest wisely, it’s more profitable than being a physician performing thousands of unnecessary operations. And a side benefit is telling the landlord employers where they can go. What do you suppose is going on in MIC, while they fail to get that technology to work on those flattops, with Russia and China watching?

Make gravity work for you, instead of letting the experts occupy your mind in the cloud. Technology is the achilles heel of corporate America. That’s why they are printing all that money, to throw at the problem. Amazon could not exist in a real economy.

Are you going to want to be on the 50th floor when the police walk out or are defunded?