Yves here. Sadly, data from past pandemics indicate that the rise in inequality seen so far is likely to be sustained.

By Guido Alfani, Professor of Economic History, Bocconi University. Originally published at VoxEU

The relationship between pandemics and inequality is of significant interest at the moment. The Black Death in the 14th century is one salient example of a pandemic which dramatically decreased wealth inequality, but this column argues that the Black Death is exceptional in this respect. Pandemics in subsequent centuries have failed to significantly reduce inequality, due to different institutional environments and labour market effects. This evidence suggests that inequality and poverty are likely to increase in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis.

There is growing concern about the possible distributive consequences of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, which has prompted many to look at past experiences for insights. After all, recent studies of long-term tendencies in wealth and income inequality have underlined the role played by major pandemics (Alfani 2020a, 2020b). Much of this literature has focused mostly on the 14th century Black Death, the terrible plague that killed about half the population of Europe and the Mediterranean and which is well-known to have had major economic consequences (Campbell 2016, Alfani and Murphy 2017, Alfani 2020c, Jedwab et al. 2020), including on the distribution of income and wealth. Based on the example of the Black Death, the view that pandemics had the power to (brutally) level inequality has become quite widespread (Milanovic 2016, Scheidel 2017). However, if we take into account subsequent episodes – from the early modern plagues to the cholera pandemics of the 19th century, and beyond – we must recognise the exceptional character of the Black Death, as later pandemics proved unable to lead to such a substantial and long-lasting reduction in economic inequality (Alfani 2020b). In contrast, for the most recent episodes like the Spanish Flu of 1918-1919 there is some evidence that instead of declining, inequality actually increased.

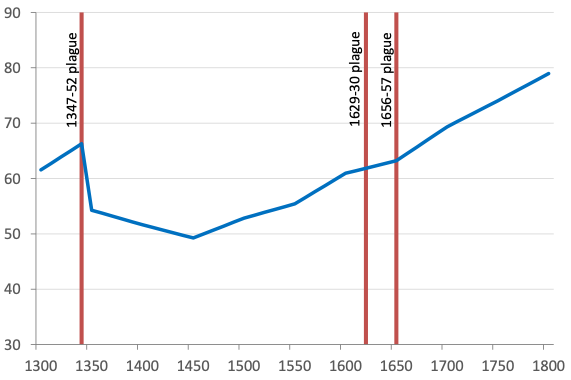

The exceptional character of the 1347-1352 Black Death is clear if we look at the available series of wealth inequality in the long run. Figure 1 shows the case of Italy, for which we have particularly good data. During the five centuries covered by the figure (1300 to 1800), the Black Death seems to have triggered the only phase of systematic decline in wealth inequality (although if the analysis is pushed into the 19th and 20th century we find another, associated to the World Wars (Piketty 2014, Scheidel 2017). In the aftermath of the Black Death, the richest 10% of the population lost their grip on between 15% and 20% of overall wealth. This decline in inequality was long-lasting, as wealth concentration did not reach the pre-Black Death level again before the second half of the 17th century. There were two main causes of the reduction in inequality.

- First, in the aftermath of the plague labour became scarce, real wages increased, and more generally the poorest strata enjoyed a boost to their bargaining power and were able to negotiate better conditions.

- The second was the fragmentation of large patrimonies caused by extremely high mortality in the context of the partible inheritance system which, in the late Middle Ages, characterised many European areas. This resulted in many people inheriting more properties than they needed or wanted, and to an unusual abundance of property being offered on the market. Together with higher real wages due to the scarcity of labour, this situation helped a larger part of the population gain access to property, thus reducing wealth inequality. Note that growing real wages are also indicative of a reduction in income inequality (Alfani 2020b).

Figure 1 The share of wealth of the richest 10% in Italy, 1300-1800

Source: elaboration based on Alfani (2020a)

We have a growing amount of evidence that the same pattern of redistribution found for Italy also involved other European areas, like France, Germany, and the Low Countries. However, the egalitarian effects of the medieval Black Death were not replicated after later large-scale plagues. Consider for example the 17th century plagues that affected southern Europe in a particularly severe way. In Italy, the plague of 1629-1630 which spread to the North and Tuscany and that of 1656-1657 that affected the central and southern parts of the Peninsula (bar for Tuscany) were characterised by mortality rates of between 30% and 40%, fairly close to the 50% or so estimated for the Black Death (Alfani 2013). But on this occasion, inequality reduction was extremely limited: it is entirely invisible in the overall tendencies shown in Figure 1, and even when we look at local dynamics it is almost undetectable based on the available historical documentation. This is probably because of the very different institutional frameworks in place at the onset of these latter pandemics. In particular, during the centuries following the Black Death, when it had become clear that plague was to remain a recurrent scourge, the richest families began to protect their patrimonies from unwanted fragmentation by using institutions, like the fideicommissum (entail), which allowed testators to derogate from the general rule of partible inheritance. This interrupted one of the key mechanisms through which plague might have reduced wealth inequality.

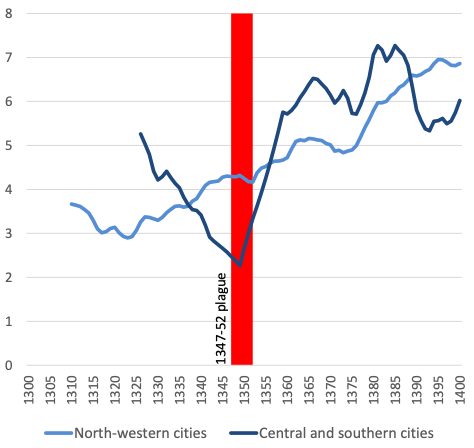

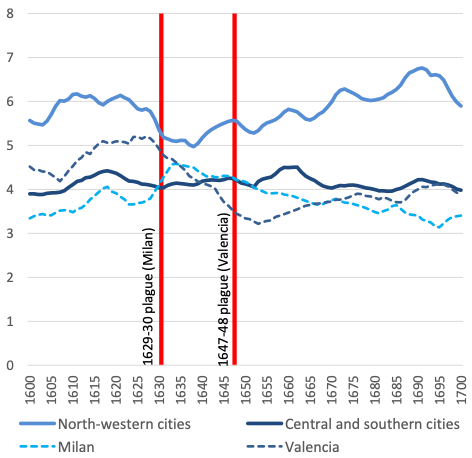

But there is more. After the 17th century plagues we see no trace of an increase in real wages, either in Italy or in other severely affected European areas, like Spain. If we compare this period to that of the Black Death the difference in the trends is quite stark, as can be noticed in Figure 2. In particular, Panel B singles out the cases of Milan in northern Italy, where the 1630 plague killed over 46% of the population, and of Valencia in eastern Spain, where the 1647-1648 plague led to an overall mortality rate of over 30%. The time series of local real wages of unskilled workers do not show any tendency towards an increase, which confirms the inability of these epidemics to cause a Black Death-style levelling.

Figure 2 Real wages of unskilled workers in European cities, 1300-1400 and 1600-1700 compared (in grams of silver)

A) Real wages and the Black Death

B) Real wages and the plagues of the 17th century

Sources: Alfani (2020b), based on data from Fochesato (2018).

The diverse long-term outcomes, in terms of inequality, of the 14th century Black Death and of the 17th century plagues suggest the need for caution when generalising historical evidence related to specific episodes – as not even epidemics caused by the same pathogen and having similar epidemiological characteristics necessarily have the same economic effects. Things become even more complicated when comparing crises triggered by different pathogens. Nevertheless, we can glimpse some possible redistributive consequences of the main global pandemic threat of the 19th century, cholera, at least for those countries – like France – for which trends in wealth inequality have been researched thoroughly (Piketty et al. 2006, 2014; Piketty 2014).

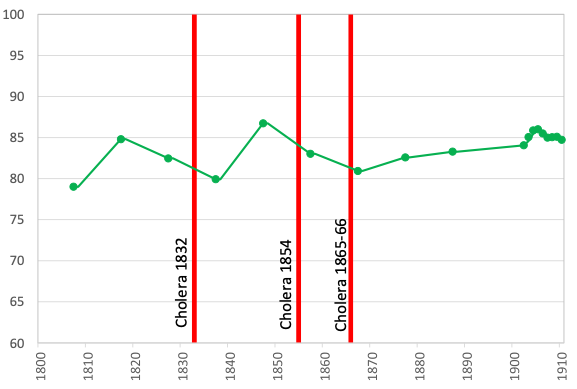

Cholera was the new disease of the 19th century. Until the beginning of the century this infection seems to have been restricted to India, but from the late 1810s it began a global spread, causing a sequence of six pandemics over little more than a century, in 1817-1824, 1829-1837, 1840-1860, 1863-1875, 1881-1896, and 1899-1923. Western countries were spared from the first pandemic, but were affected, to various degrees, by all the others (Bourdelais 1987, Kohn 2007). In Europe, the second, third, and fourth pandemics had particularly serious consequences. France was badly hit, especially in 1832 (102,000 victims) and in 1853-1854 (143,000 victims). If we look at the trend in wealth inequality (Figure 3), it appears that both these outbreaks are placed in correspondence of phases of inequality decline.

These data have to be interpreted very conservatively, as for most of the period we have only one observation every ten years, starting in 1807. However, they do allow us to highlight another possible mechanism through which large-scale pandemics of the past might have reduced inequality: the extermination of the poor. Because its spread is favoured by unhealthy and crowded living conditions, cholera affected the poorest groups much worse than all other strata, especially in cities, thus it tended to curtail the lower part of the distribution – which would have led to a reduction in inequality among the survivors even in the absence of any other distributive effect (Alfani 2020b).

Figure 3 Wealth inequality and cholera pandemics in France, 1800-1910 (share of the richest 10%)

Source: Alfani (2020b), based on data from WID (World Wealth and Income Database).

Together, the cases of cholera and plague allow us to highlight an important point: apart from the initial conditions, the overall mortality rates and the structure of mortality also play a crucial role in determining the redistributive effects of an epidemic. The 17th century plagues, while they had a limited impact upon overall inequality as measured by a Gini index or by the wealth share of the richest, nevertheless were able to cause some reduction in the prevalence of poverty, but this was simply because they tended to exterminate the poor, just as, centuries later, also cholera would do (Alfani 2020b). The medieval Black Death had major consequences on the labour market, but this was because it led to horrifically high mortality rates. In the case of other events, such as the Spanish Flu of 1918-1819, that may claim a high number of victims but through much lower mortality rates (0.25-0.5% in the case of the Spanish Flu: Johnson and Mueller 2002), factors like the contraction of the labour force simply do not operate in the same way, and their distributive consequences are easily overcome by those of other factors.

This is relevant to our understanding of the possible distributive effects of Covid-19, which from the epidemiological point of view is surely more similar to the Spanish Flu than to the Black Death. While studies of the impact on inequality of the Spanish Flu remain rare, we have some evidence that it led to increases in income inequality, for example in Italy (Galletta and Giommoni 2020), mostly because the associated economic crisis led to unemployment and to income loss especially for the poorest and more economically fragile population. Indeed, a striking study of Sweden estimates that for every death caused by the Spanish Flu, there were four new poor people who had to ask for public help at poorhouses (Karlsson et al. 2014). Also in the case of Covid-19, much concern has been expressed about rapidly growing unemployment, especially among the poorest, not only due to the pandemic itself (e.g. job loss for infected people or for those who will long suffer poor health as a consequence of the infection) but also as a result of the containment policies (like lockdowns of various kinds) that have been applied worldwide (OECD 2020).

What the historical experience of the last seven centuries seems to suggest is that in the case of this specific pandemic, the mechanisms leading to an increase of inequality and poverty in the aftermath of the crisis will prevail. From a certain point of view, this is good news because it comes from the fact that the final mortality caused by Covid-19 will be orders of magnitude lower than that associated to levelling catastrophes like the Black Death. But from another point of view, this means that governments worldwide need to be prepared to manage, and possibly to prevent, the social crisis that seems sure to follow the current health crisis.

See original post for references

I still want to read “The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality From the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century” by Walter Scheidel. It says similar kinds of things. See:

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/02/scheidel-great-leveler-inequality-violence/517164/

Thank you for reminding me to order this book! I am familiar with Scheidel and his analysis of Europe after the fall of Rome, but if the reviews are correct, Scheidel does have another piece to add to the puzzle that is history! One thing we can all be sure of: those in power do not give it up easily!

And thank you, Yves for presenting this article. Covid-19 is not like the Black Death and it irks me to hear Covid compared to it. Covid is a disease that the wealthy can protect themselves from for the most part and continue as though not much has changed. Not so for the Black Death! Like this author points out, the Black Death was far more of a human catastrophe than Covid will ever be so we cannot compare what will happen next to us to what happened then.

One can read a number of interviews of Scheidel online that give very good abbreviated views of his book.

I bought the book and it gives more details about Scheidel’s research.

If I can summarize, inequality gets worse in a stable society until “something happens” (great plague, world war, a revolution, state collapse).

Here is a quote from Scheidel : ““All of us who prize greater economic equality would do well to remember that with the rarest of exceptions, it was only ever brought forth in sorrow. Be careful what you wish for.””

Perhaps the historian Scheidel could well predict future events better than the “always grow the pie” economics profession as we move toward climate change.

Maybe our next great catastrophe will result from the effects of climate change if capitalism continues to raid all the resources of the earth.

This episode from the Ancient Greece Declassified podcast has Scheidel as a guest, on historical inequality generally but touching on pandemics in particular. He is very informative and engaging:

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/24-a-history-of-inequality-w-walter-scheidel/id1158506284?i=1000440285494

I was recently talking to a friend in the housing industry here in Ireland – he said that the housing market has held up surprisingly well and developers are optimistic. What they are finding is that the core ‘customer’ – people on mid to higher incomes, regular jobs, are generally doing ok, and have even found themselves with surplus cash thanks to cancelled holidays. The banks are still lending money to mortgages. As he bluntly put it – the people who are suffering economically from the pandemic (i.e. primarily retail/tourism service workers) are people who were not earning enough anyway to buy a house.

Following the last crash here the Irish Central Bank placed strict controls on ‘buy to let’ type mortgages, which it rightly considered a major pro-cyclical push factor in the market – this has had a significant impact compared to the UK, where this is still a major part of the market and likely helps exacerbate inequality. But I wonder if a flight of workers to rural areas post Covid might encourage more people to buy a second home, renting out their urban home.

I can’t see many scenarios where Covid does not exacerbate inequality under current economic conditions, but I think there will also be other impacts – specifically, small to medium businesses and the self employed are being hit very hard, while mid to higher income white collar workers are getting off largely unscathed. I think we are seeing more than just ‘the poor getting poor and the rich getting richer’, we are are seeing a significant shift even within the classes and the long term results could be quite complex. We may, for example, see sectors now move far more to mechanisation (in, for example, food production), while the power of white collar salaried workers might actually have increased.

One has to wonder how much killing off the poor has historically statistically improved inequalities subsequent to all natural and man-made disasters.

Trump’s laissez-faire attitude toward Covid encourages his minions to snub the mask–never mind if that herd mentality leads to herd morbidity and mortality. That more vulnerable poor and middle class Americans will die is a feature, not a bug. For the wealthiest Americans, that is.