Yves here. CalPERS gets such a disproportionate amount of press attention than most other US public pension funds, which results in too many of them getting a free pass on similarly shoddy practices. This article by Matthew Cunningham-Cook focuses on the role of Scott Stringer, currently New York City Comptroller, who also oversees the New York City pension system called New York City Employees’ Retirement System, or NYCERS. And it’s worth noting that a connection to Blackstone increasingly is a badge of dishonor.

Cunningham-Cook describes how Stringer has been too friendly to private real estate fund managers like Blackstone and Carlyle, to the detriment of the pension funds’ performance. That should come as no surprise. Stringer was previously Manhattan Borough President and launched a bid for the Comptroller seat. Former attorney general Eliot Spitzer jumped into the Comptroller race, challenging Stringer in the primary. Even though Spitzer had a large lead, it eroded as the Stringer campaign, the Democratic party machine, and Wall Street all went after Spitzer, focusing on his sexual improprieties.

We had supported Spitzer and called on him to use the Comptroller position to go after wide-spread abuses in private equity. It should come as no surprise that the status quo candidate continued to cozy up to Big Finance, regardless of the cost to beneficiaries and taxpayers. From a 2013 post, Memo to Eliot Spitzer: Private Equity Firms are Scamming New York City:

Let’s start by examining the relationship between private equity firms and the New York City Comptroller.

The New York City employee pension system is one of the largest private equity investors in the U.S., with $8.3 billion invested in this strategy. Though a board of trustees is technically the fiduciary for each of the City pension funds, and the Comptroller has only one seat on each of those boards, in reality, the City Comptroller is, to an extreme degree, first among equals on all of the boards. The reason for his disproportionate influence is that all of the City pension funds are managed day-to-day by a combined staff, and those staff members are all employees of the New York City Comptroller, making him effectively their boss.

Moreover, the super-secret contracts that the NYC pension funds enter into with PE firms are held at the Comptroller’s office, as are the super-secret cash flows showing what the pension funds contributed to the funds and what they got paid out in return. It’s impossible to overstate the importance of the Comptroller’s access to PE fund contracts (known as limited partnership agreements or LPAs) and cash flows. PE firms accomplish much of their investor scamming via fees that are contrary to LPA terms and that they take from portfolio companies owned by the funds they manage. The PE firms also scam by charging the funds they manage for expenses that the LPA says should be paid by the PE firm itself….

The sad truth is nobody who invests in PE looks closely at whether PE firms are complying with the fee and expense provisions of their agreements. Part of the reason is that the PE firm lawyers draft the terms in these LPAs to be almost incomprehensible. Another reason is, astonishingly, that PE investors have accepted the argument of PE firms that these contract provisions are a form of “trade secret.” Public pension fund investors have almost universally acceded to the demands of PE firms to exempt the LPAs and cash flow reports from state FOIA laws, which keeps the eyes of the press and the public off the documents.

This information lockdown prevents a worst-case scenario for scamming PE firms, that a mid-level accounting employee at a portfolio company would use public documents to compare the payments made to fund investors with what was taken from the portfolio company where the accountant works. State qui tam laws, which are designed to prevent precisely this type of abuse by awarding a portion of the government’s recovery to people who uncover fraud, would provide a powerful incentive for employees at portfolio companies to rat out their PE overlords. But that’s not going to happen as long as public pension fund PE investors keep the contracts and cash flows behind the FOIA wall. However, the New York City Comptroller has access to this critical information. Hence the freakout at the prospect that Spitzer might get the job.

Back to the current post. The picture that Cunningham-Cook paints of NYCERS getting less on its real estate investments and paying more in fees is understated. It’s bad enough that NYCERS doesn’t publish the returns for all of its investments net of fees; that’s a big red flag. But on top of that, even the investors that claim they produce “net of fees” returns don’t because so many fees are hidden. It takes a lot of effort, as in pushing the general partner (the fund manager) to cough up some of the missing numbers. We pointed out this sorry state of affairs in 2015; there has only been modest improvement since then:

A major standard-setter in the private equity industry, CEM Benchmrking, has thrown down a gauntlet to investors. It said in a recent report that it is impossible for private equity investors to know how much they are paying in private equity fees and costs. Moreover, CEM also points out that most public pension funds are not complying with government accounting standards in how they report private equity fees and costs, and that based on their benchmaring efforts with the South Carolina Retirement System Investment Commission and foreign investors, most public pension funds are missing at least half of the total costs.

This report is particularly significant because CEM is an authoritative voice in the investment industry. It didn’t simply say that public pension funds are out to lunch as far as not understanding what they were investing in. It also pointed out as a result, the public pension funds have been not been reporting fees accurately are out of compliance with government reporting requirements.

As for NYCERS, Cunningham-Cook unintentionally muddies the waters for newbies by focusing on “private equity real estate”. Private equity is investing in privately-held companies, as in ones whose shares are not registered with the SEC or other securities regulator. That is completely different than investing in private portfolios of real estate (office buildings, shopping centers, apartment complexes) even though the biggest private equity firms also play in real estate. The two types of investment have different returns and fee levels. A recent study by Richard Ennis in the authoritative Journal of Portfolio Management depicts private real estate underperformance and fee levels as worse than Cunningham-Cook’s sources indicate:

During the last two decades, private-market real estate underperformed REITs by a wide margin. In a 2019 study, CEM Benchmarking determined that institutional portfolios of private-market real estate, including core and non-core properties, underperformed listed real estate by 2.8% a year between 1998 and 2017.16 With comparable volatility (adjusted for return smoothing), REITs achieved much better risk-adjusted performance than private-market real estate over the 20-year period, with a Sharpe ratio of 0.44 compared with 0.33 for pri- vate real estate. Bollinger and Pagliari (2019) determined that non-core real estate significantly underperformed between 2000 and 2017. They calculated the annual alpha of “opportunistic” funds at -2.85% and that of “value-added” at -3.46% relative to core funds. The authors concluded that the largest contributor to the poor showing of non-core investments was their cost, which they put at 3% to 4% per year of the equity portion of investment value.

The Ennis paper also found that NYCERS generated negative alpha (as in its investment activities destroyed value) but not as badly as CalPERS. Ennis also explained why one of the widely-claimed justifications for investing in real estate was bogus. It’s widely believed to perform differently than stocks, or in investment-speak, not to co-vary much with them. If that were true, adding real estate to an investment portfolio would reduce year-to-year risk without sacrificing long-term returns. From Ennis:

Significant real estate cash flows and valuations are reflected in the financial statements of publicly traded corporations and are priced into their shares. It has been estimated that real estate assets at market value account for 40% of US corporate assets (see Nelson, Porter, and Wilde 1999)….real estate remains an important asset of corporate America, and corporations buy and sell properties in the same markets as real estate asset managers. Therefore, when you invest in a stock index fund, you get a big slug of genuine, diversified, valuable, income-producing real estate. Furthermore, $1.3 trillion of pure real estate assets now exist in the form of REITs, which are included in the Russell 3000. It should come as no surprise, then, that institutional funds’ real estate returns would be captured by the returns of the US stock market.

Now, after that preamble, to Cunningham-Cook’s takedown of Scott Stringer.

By Matthew Cunningham-Cook. Originally published at New York Focus

hen New York City comptroller Scott Stringer announced his mayoral campaign on September 8, he pledged that under his administration, there would be “no more giving away the store to developers.”

“No more unaffordable affordable housing,” he said. “We will put an end to the gentrification industrial complex and end policies that perpetuate a cycle of segregation in our neighborhoods.”

But public pension fund investments made under Stringer’s watch heavily subsidized private equity real estate—and cost the city hundreds of millions of dollars when they underperformed.

As comptroller, Stringer oversees the investment strategy of the New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS), the city’s largest pension fund. During Stringer’s tenure, NYCERS has scaled up its investments in high-fee, high-risk private equity real estate.

From 2016 to 2019, NYCERS increased its portfolio in private equity real estate by 45%. This included the investment of $150 million of new assets into the Blackstone Group, a private equity firm which has been accused by the UN of contributing to the global housing crisis through its aggressive eviction practices and dramatic rent hikes.

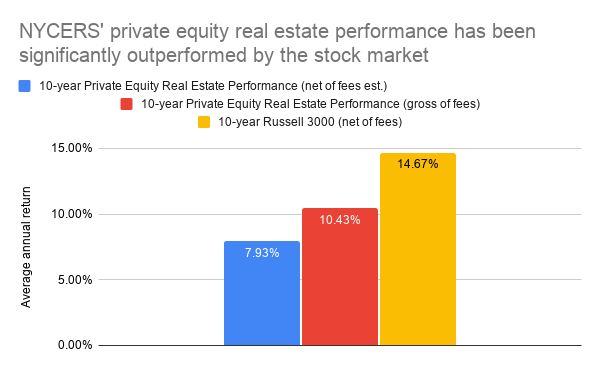

Returns on these investments have significantly lagged the stock market. A New York Focus analysis of NYCERS’ annual reports from 2016 to 2019 has found that investments in private equity real estate have cost the city over $260 million in lost performance relative to the stock market, in addition to $110 million in reported fees, for a total of at least $370 million.

“Even on the reported values, NYCERS’ private equity real estate portfolio has dramatically underperformed,” said Edward Siedle, a former Securities and Exchange Commission attorney who received the largest whistleblower award in the agency’s history in 2019.

When the pension underperforms, the cost is ultimately borne by city taxpayers, whose annual contribution to the pension fund is determined based on returns. Smaller returns means that a larger part of the city budget is allocated to pensions.

This means that money that could have been used to repair public housing or ensure ventilation in the city’s schools is now making up a shortfall generated by poor performance by Wall Street money managers.

High Fees and Poor Performance

Jeff Hooke, an investment banker and senior lecturer at Johns Hopkins University, said that the $110 million in reported fees is a significant underestimate of how much the city actually pays in fees.

Accounting for fees like the carried interest fee, which NYCERS does not report, Hooke’s research has found that “fees are 2.50% of private equity assets under management, not 1% or 1.5% as indicated” in the pension fund’s annual reports. The actual amount the city paid in fees to private equity real estate firms from 2019 to 2019, in other words, may be as high as $183 million.

Officially, NYCERS’ 2019 financial reports show a 10.43% annualized return for its private equity real estate portfolio over the last decade, clocking in at 71% of the Russell 3000 stock index’s annualized return of 14.67%. But because the pension fund reports its 10-year returns without accounting for fees, the actual performance of the portfolio is even lower. Applying Hooke’s estimate of 2.5% fees, NYCERS’ private equity real estate investments have earned the city just 55% of what it would have made investing in the Russell 3000.

Even this lower estimate could be overestimating NYCERS’ performance, because it relies on asset values calculated by the money managers themselves. Private equity real estate, Siedle said, is “highly susceptible to inflated valuation because the values are unilaterally determined by the managers.” Based on decades of experience in pensions, Siedle typically presumes that reported performance is likely worse than reported—and never better.

“Real estate is one of the least transparent investments,” Siedle concluded. “it has all kinds of hidden and embedded fees, and remarkably there’s been less scrutiny of real estate fees than even standard private equity fees.”

“Just Give Money to a Gambler and Send Them to Vegas”

Why do pension funds continue to invest in an industry that performs so poorly? Finding information about the pension fund’s decision-making process can be difficult; unlike nearly every other major public pension fund, NYCERS does not post its minutes online.

Stringer’s office did not respond to a detailed list of questions sent by New York Focus. In 2015, as this writer reported at the time, Stringer strongly pushed for a change in state law that would have allowed a larger expansion into private equity real estate and other so-called “alternative investments.” Investing more in these areas, said Stringer’s spokesman, “will allow the pension boards to achieve a superior risk-adjusted return.”

Many pension funds justify investments like private equity real estate by arguing that they are not correlated with broader stock and bond markets, and thus add diversity and protect against risk. As the alternative investment data company Preqin wrote in a 2016 newsletter, “real estate remains a crucial part of many pension fund portfolios, with investments in the asset class able to mitigate against fluctuations in traditional bond and stock markets.”

But according to Siedle, this argument holds little water.

“If you want an investment that does not correlate with traditional stocks and bonds, just give money to a gambler and send them to Vegas,” he said. “Those won’t correlate and thus mitigate the fluctuations of the market. It all depends if you’re willing to take on that risk.”

“Publicly traded investments have clearly ascertainable values and clearly ascertainable performance,” Siedle added. “The minute you migrate away from the public market, you’re incurring substantially greater risk. As a prudent fiduciary, the question is: Can you justify that divergence or that migration? You should expect returns that substantially outperform public markets given the risk.”

Managing the pension funds is arguably the comptroller’s most powerful role, but Stringer’s record on pensions has thus far avoided media scrutiny. The comptroller sits on the boards of all five city pension funds, which currently have $221 billion in assets, and employs and supervises the investment staff of the pension funds in the Bureau of Asset Management. NYCERS’ board also has representation from the city’s mayor, public advocate and borough presidents, and the major city labor unions, which must approve investments.

City Council Member Brad Lander, who is running for comptroller, said he would look at the performance of private real estate and other alternative investments if elected. “The pension funds need to be invested in a way that maximizes long term value and minimizes fees,” said Lander. “We need to take a good hard look at whether private equity firms do that.”

Pension fund investments in private equity have long been tainted by corruption. The city’s first major commitments into alternative investments were led in the 1990s by then-city comptroller Alan Hevesi, who later went to prison for receiving bribes to place alternative investments with the state pension fund as state comptroller. Hevesi also accepted large campaign contributions from Blackstone’s CEO, Stephen Schwarzman, even as the firm won lucrative contracts from the state pension fund. The SEC banned these types of contributions in 2010.

Beyond Blackstone, private equity real estate investments made on Stringer’s watch include $90 million to the Carlyle Group, whose executives were found to have bribed Hevesi, and $260 million to Brookfield, a secretive real estate firm that owns large swaths of the city’s real estate and recently courted congressional investigationby bailing out the family of Jared Kushner from its debt-laden investment on 666 Fifth Avenue.

“You Can’t Run for Mayor on Real Estate Speculation”

Beyond the concerns about underperformance, high fees, and opacity is the social impact of the investments. Cea Weaver, coordinator of the Housing Justice for All coalition, which played a leading role in securing the landmark 2019 expansion of renter’s rights, pointed out that housing activists are almost always battling with Brookfield and Blackstone. The city’s investments in these firms, she argued, give rise to a major conflict of interest on housing policy.

“Brookfield is really invested in rent stabilized housing, and there is this problem where in order for these portfolios to do well, they have to evict rent stabilized tenants,” said Weaver.

Weaver pointed out that the change in rent regulations upended the future values of many private equity real estate managers’ properties, because it barred them from turning some rent stabilized apartments into market rate housing.

“The rent laws changed the speculative value of one million apartments in the city with ramifications for private equity investors,” Weaver said, pointing to Brookfield’s investment in a portfolio of rent-stabilized apartments in East Harlem as one example.

“Blackstone owns Stuy Town, where they have effectively stopped doing repairs. From my perspective, there’s this massive problem,” Weaver added. “If we succeed politically the investments will do worse. The reason why Stringer should be divesting from real estate is because tenants’ political agenda is at odds with them.”

“You can’t run for mayor on real estate speculation,” Weaver concluded. “He needs to not be a participant in it.” ![]()

The article makes a lot of good points, especially on fees, but the benchmarking is terrible. The Russell3000 is not the right comparison. There are real estate indices, or even using quoted REITs as in the pre-amble would make much more sense. I can’t believe that there aren’t independent valuers for the assets too – its not that expensive or hard.

A big idea of investing direct into property is supposed to cut out the costs/ agency issues of REITs – this sounds like a mess that has got it all wrong!

Yes, another paper shows that private real estate is way more expensive than REITS: $7.5 billion in excessive fees and persistent negative alpha:

https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2019/12/12/private-real-estate-fund-categories-a-risk-return-assessment/

The Russell 3000 was a more generous comparison than the NAREIT, which performed about 200bp better (apologies for the estimate, writing this from my phone!

The rent law may well have changed the “speculative value” on a million apartments, it didn’t do anything about real economy ability to pay.

With the Fed’s perpetual reflation of assets through QE by whatever name, the unreality of asset valuations continues it’s long march to a no doubt revolutionary future!

This is just one of many realms where private finance is siphoning off real value from the overall economy, but its one that points to an immanent need for the Fed to start underwriting pensions. Thank you for staying on top of this beat from here to Kentucky to California!

Interesting tangent for people interested in NY politics. This site is the only one I’ve found that rates each individual state legislative race. (click menu in the lower left to change what data you are looking at) They currently rate the NY assembly as a 100% chance of returning a Dem supermajority, and a 62.1% chance of a NY state senate supermajority.

With this awful election cycle the one bright light might be watching Cuomo vetoes get overruled over and over again.

Why can’t I stop thinking of Stringer Bell:

https://thewire.fandom.com/wiki/Russell_Bell