Yves here. While this paper does a good job of compiling and analyzing data about Covid deaths and excess mortality, and speculating about deaths of despair, I find one of its assumptions to be odd. It sees Covid-related deaths of despair as mainly the result of isolation. In the US, I would hazard that economic desperation is likely a significant factor. Think of the people who had successful or at least viable service businesses: hair stylists, personal trainers, caterers, conference organizers. One friend had a very successful business training and rehabbing pro and Olympic athletes. They’ve gone from pretty to very well situated to frantic about how they will get by.

While Mulligan does mention loss of income in passing in the end, it seems the more devastating but harder to measure damage is loss of livelihood, thinking that your way of earning a living might never come back to anything dimly approaching the old normal. Another catastrophic loss would be the possibility of winding up homeless, particularly for those who’d never faced that risk before.

By Casey Mulligan, Professor of Economics, University of Chicago and former Chief Economist of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. Originally published at VoxEU

The spread of COVID-19 in the US has prompted extraordinary steps by individuals and institutions to limit infections. Some worry that ‘the cure is worse than the disease’ and these measures may lead to an increase in deaths of despair. Using data from the US, this column estimates how many non-COVID-19 excess deaths have occurred during the pandemic. Mortality in 2020 significantly exceeds the total of official COVID-19 deaths and a normal number of deaths from other causes. Certain characteristics suggest the excess are deaths of despair. Social isolation may be part of the mechanism that turns a pandemic into a wave of deaths of despair; further studies are needed to show if that is the case and how.

The spread of COVID-19 in the US has prompted extraordinary, although often untested, steps by individuals and institutions to limit infections. Some have worried that ‘the cure is worse than the disease’. Economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton mocked such worries as a “pet theory about the fatal dangers of quarantine”. They concluded in the summer of 2020 that “a wave of deaths of despair is highly unlikely” because, they said, the duration of a pandemic is measured in months whereas the underlying causes of drug abuse and suicide take many years to accumulate (Case and Deaton 2020). With the extraordinary social distancing continuing and mortality data accumulating, now is a good time to estimate the number of deaths of despair and their incidence.

As a theoretical matter, I am not confident that demand and supply conditions were even approximately constant as the country went into a pandemic recession. Take the demand and supply for non-medical opioid use, which before 2020 accounted for the majority of deaths of despair.1 I acknowledge that the correlation between opioid fatalities and the unemployment rate has been only weakly positive (Council of Economic Advisers February 2020, Ruhm 2019). However, in previous recessions, the income of the unemployed and the nation generally fell.

In this recession, personal income increased record amounts while the majority of the unemployed received more income than they did when they were working (Congressional Budget Office 2020).2 Whereas alcohol and drug abuse can occur in isolation, many normal, non-lethal consumption opportunities disappeared as the population socially distanced. Patients suffering pain may have less access to physical therapy during a pandemic.

On the supply side, social distancing may affect the production of safety.3 A person who overdoses on opioids has a better chance of survival if the overdose event is observed contemporaneously by a person nearby who can administer treatment or call paramedics.4 Socially distanced physicians may be more willing to grant opioid prescriptions over the phone rather than insist on an office visit. Although supply interruptions on the southern border may raise the price of heroin and fentanyl, the market may respond by mixing heroin with more fentanyl and other additives that make each consumption episode more dangerous (Mulligan 2020a, Wan and Long 2020).

Mortality is part of the full price of opioid consumption and therefore a breakdown in safety production may by itself reduce the quantity consumed but nonetheless increase mortality per capita as long as the demand for opioids is price inelastic. I emphasise that these theoretical hypotheses about opioid markets in 2020 are not yet tested empirically. My point is that mortality measurement is needed because the potential for extraordinary changes is real.

The Multiple Cause of Death Files (National Center for Health Statistics 1999–2018) contain information from all death certificates in the US and would be especially valuable for measuring causes of mortality in 2020. However, the public 2020 edition of those files is not expected until early 2022. For the time being, my recent study (Mulligan 2020b) used the 2015–2018 files to project the normal number of 2020 deaths, absent a pandemic.

‘Excess deaths’ are defined to be actual deaths minus projected deaths. Included in the projections, and therefore excluded from excess deaths, are some year-over-year increases in drug overdoses because they had been trending up in recent years, especially among working-age men, as illicit fentanyl diffused across the country.

I measure actual COVID-19 deaths and deaths from all causes from a Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) file for 2020 that begins in week five (the week beginning 26 January 2020) and aggregates to week, sex, and eleven age groups. To minimise underreporting, I only use the data in this file through week 40 (the week ending 3 October). In separate analyses, I also use medical examiner data from Cook County, Illinois, and San Diego County, California, which indicate deaths handled by those offices through September (Cook) or June 2020 (San Diego) and whether opioids were involved, and 12-month moving sums of drug overdoses reported by CDC (2020) through May 2020.

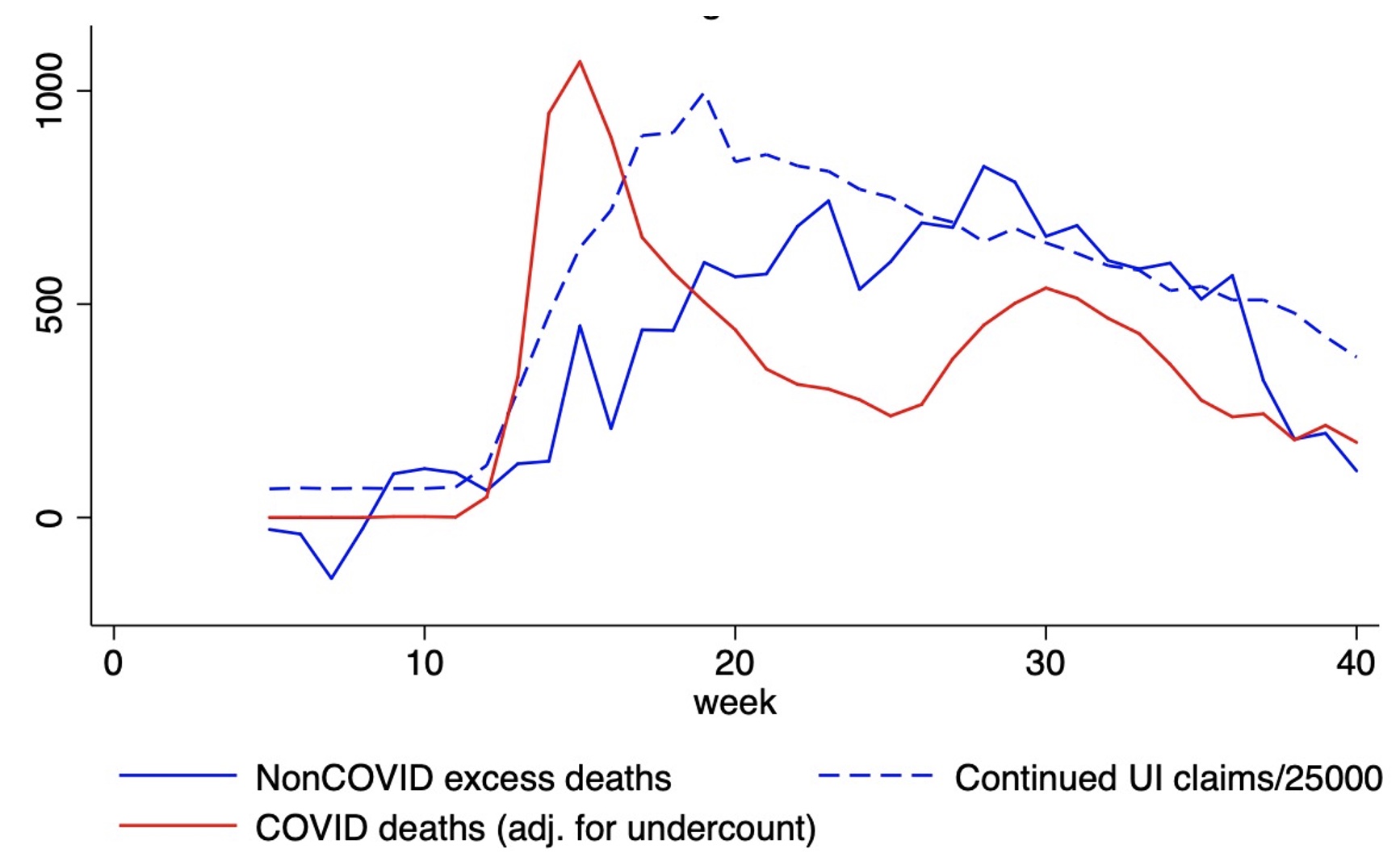

Mortality in 2020 significantly exceeds what would have occurred if official COVID-19 deaths were combined with a normal number of deaths from other causes. The demographic and time patterns of the non-COVID-19 excess deaths (NCEDs) point to deaths of despair rather than an undercount of COVID-19 deaths. The flow of NCEDs increased steadily from March to June and then plateaued. They were disproportionately experienced by working-age men, including men as young as 15 to 24. The chart below, reproduced from Mulligan (2020b), shows these results for men aged 15–54. To compare the weekly timing of their excess deaths to a weekly measure of economic conditions, Figure 1 also includes continued state unemployment claims scaled by a factor of 25,000, shown together with deaths.

Figure 1 2020 weekly excess deaths by cause (men aged 15–54)

NCEDs are negative for elderly people before March 2020, as they were during the same time of 2019, due to mild flu seasons. Offsetting these negative NCEDs are about 30,000 positive NCEDs for the rest of the year, after accounting for an estimated 17,000 undercount of COVID-19 deaths in March and April.

If deaths of despair were the only causes of death with significant net contributions to NCEDs after February, 30,000 NCEDs would represent at least a 45% increase in deaths of despair from 2018, which itself was high by historical standards. At the same time, I cannot rule out the possibility that other non-COVID-19 causes of death or even a bit of COVID-19 undercounting (beyond my estimates) are contributing to the NCED totals.

One federal and various local measures of mortality from opioid overdose also point to mortality rates during the pandemic that exceed those of late 2019 and early 2020, which themselves exceed the rates for 2017 and 2018. These sources are not precise enough to indicate whether rates of fatal opioid overdose during the pandemic were 10% above the rates from before, 60% above, or somewhere in between.

Presumably, social isolation is part of the mechanism that turns a pandemic into a wave of deaths of despair. However, the results so far do not say how many, if any, come from government stay-at-home orders versus various actions individual households and private businesses have taken to encourage social distancing. The data in this paper do not reveal how many deaths of despair are due to changes in ‘demand’ – such as changes in a person’s income, outlook, or employment situation – versus changes in ‘supply’ – such as the production of safety and a changing composition of dangerous recreational substances.

See original post for references

I agree with Yves’s counter-argument though I must declare an interest, having done work on quality of life for 20 years and hope I’m not breaking site rules (given recent reminders about what is and isn’t ok).

The excess deaths (particularly among men) certainly to me seems more consistent with a collapse in one’s ability to do the “valued things in life” and prioritise (to SOME extent) economic outcomes over relationships. After all, the old trope that men cope less well than women with retirement is found in happiness, quality of life and other such data.

Whether or not one agrees with me, surely a test as to whether the authors or Yves has the better explanation for the excess deaths would involve looking at well-being and mortality of men who retire earlier than they’d like vs that of those whose spouse died earlier than expected (including the proper control groups).

Thanks for posting.

It would be interesting to find out the following:

1. Did the states with the most generous unemployment benefits (like MA or NJ) have fewer deaths of despair that the states with much stingier benefits?

2. Did the states which imposed various shutdowns (mainly blue states) have more deaths of despair than the states which stayed open, like SD or Florida?

My guess is that deaths of despair are too idiosyncratic to blame on Covid lockdowns, but I am not an expert at all about this.

They could also look for the link with 0% interest on people’s saved money and seeing no f..ing end in sight as the beatings continue. Going down to zero does not make the people jolly.

It used to be only men who would upon meeting another man, where the first question is likely ‘What do you do for a living?’, but with the advent of as many women working, probably appropriate there too.

Nobody ever asks firstly what your hobby is or what sports team you follow, as the job query tells you everything about the person in one fell swoop.

There’s a lot of people whose jobs were kind of everything in their lives, who had never gone without work ever, that are now chronically unemployed.

What a person does for a living, in some cases, doesn’t tell the whole story about an individual, but rather tells you how that person acquires their economic sustenance as opposed to who that person is. The hobbies or activities that her or she engages in when not under the thumb of an employer may express and define more of who that person is in terms of their personality, character, politics, etc.

Anybody who has studied suicide readily appreciates that the act is impulsive. Case & Deaton are probably correct in the limited sense of economic despair derived from transitioning away from fossil fuels and industrial production to jobs requiring education unreachable to middle-aged coal miners. However, those deaths were likely derived from easy access to opioids. Most of those job losses led workers to make disability claims (achy backs) to extend income. The treatment for achy back is pain killers – oxy-something or other back then. Those same pills killed the pain of failure. Over time, addiction set in and, according to Koob & LeMoal’s 2008 addiction model, increased consumption becomes necessary to stay pain-free. Physicians would surely not up dosages indefinitely and that put addicts on the street literally. All that took time to evolve. But times have changed. Using your family doc to get you high is no longer an option. So, Mulligan makes sense.

As an internist with boots on the ground – I cannot express enough gratitude that these kinds of reports are getting out.

As busy as I have been this past year with COVID, the actual patients struggling with anxiety and depression have just dwarved the actual COVID numbers.

I cannot even begin to tell you the heartbreak of being a provider and having 20-40 year old young men in your office crying their eyes out. Lots of job loss, lots of income issues, lots of not being able to pay for things for your kids. All the while being completely unable to find other work or extra work. It is truly a nightmare for these people. And the attitude by so many of the lockdown Karens who seem to have no conception of how this is all going down for these young people has been deeply worrisome to me.

It is really not getting better – if anything slowly getting worse.

I would agree with the article above that loneliness is a problem – this is for the minority – mainly older people and should not be dismissed.

Loneliness is not the big problem however, in my experience. The big problem is the economic despair for our young people and the complete loss of socialization for our teenagers and kids.

And I have no clue what the answer is.

This is an important post, thank you.

The unemployment rate for people earning more than $65,000 is down during the pandemic.

The unemployment rate for factory jobs is generally down during the pandemic.

It is the hospitality jobs in bars, restaurants, and hotels that have been devastated. The likelihood of more air travel bans will make this worse.

Once again we are met with a great problem — which is that even if jobs are not necessary to sustain the economy, jobs are necessary to sustain families especially fathers.

IM Doc — I deeply appreciate your unique perspective and experience. Thank you for sharing both so generously with the NC Commentariat. I imagine many here agree, but are wary to chime in for fear of creating more work for the moderators. Hope this comment is in line with the current site policy.

/Carla

I can’t say if this still holds, but I grew up inside the military, and long before it was true anywhere in the US, every neighborhood I lived in on base was integrated, my schools were integrated, we all got the same healthcare at the same hospital, and shopped at the same commissary and exchange.

After years overseas on military bases, the culture shock of coming to civilian America was massive. The inequality I saw staggered me. As did the lack of any real communal sense of people generally being “in this” together. And the individual drive for ever more money. That was simply NOT part of the ethos of the military I grew up inside. For sure, no general was paid hundreds of times what a private earned. The apartment assigned a field grade officer was no different from the apartment assigned an NCO. There was no differentiation, in choosing friends, between the children of officers and the children of NCOs or enlisted men/women.

In reuniting with classmates, I learned that a lot of us have struggled with American civilian life. The communal ethos we grew up with, and the definition of what constitutes “success” or “merit” is that alien to us.

It is ironic that, at least in the military I grew up in, daily life was more socialist than the daily life I lived in one of the bluest of the blue cities in the U.S.

Integrated in what sense? Ethnically, class-based, gender?

She made clear there were no noticeable class differences. The military is reportedly very race-blind by American standards, so I assume that is what she means. “Integrated” isn’t a word I normally see with gender plus I believe (and maybe she will pipe up) that even though I bet it much better than most US workplaces, it still has a way to go.

Of course no military base puts up with the sort of anti-social behavior we routinely see on the streets of American cities- no throwing trash out of the car windows; no rowdy teenagers making noise at 2 am or harassing passersby at the local supermarket/PX; no homeless tents; no boomboxes; no trash in the front yard; no purse snatching by gangs of youth; no graffiti spraying… the list is almost endless.

And why? Because any kid who causes a problem potentially effected the parents’ career- your parents are held responsible for your behavior. That can be very good or not-so-good. I remember when boys from military families began to grow their hair long in the 1960s and the family fights that followed because the child’s behavior reflected on the parents, as in “Why can’t you control your kid?”… and the military believes deeply in the chain-of-command at work and in the household.

My experience? I taught at a high school next to a military base in the late 1960s; I spend time on military bases now because they house archives I use; I’ve seen the family cost when people are deployed overseas; and I’ve gone to the funerals.

One final though. When the White House needed lots of enlisted techies nearby in the 1980s, they authorized new quarters to be built in Anacostia at Bolling Air Force base base where the Presidential helicopters are kept. Anacostia is all black with lousy and dangerous schools. The enlisted guys flat out refused to send their kids to the local schools. When they were told “But these are your new quarters so your kids go to the local schools” they voted with their feet- they handed in papers to leave active duty. They had skills and even better, active top secret clearances and could get good jobs. So the military quietly caved in. all of the military kids were given a free ride to go to schools in Fairfax County, VA across the river. They even got tuition paid at local Catholic schools. To put it mildly, these were kids with parents who really invested time and effort into raising them.

Time, money, and work was done to have those military parents living in peaceful, non chaotic, safe communities which gave those parents the ability to raise their children and to get good jobs; Anacostia’s community is probably considered disposable which means that they have none of what made the military community so good.

Of course, creating those good conditions for poor or minority communities is the un-American evil, no good socialism and a waste of taxpayer money while doing so for the military community is all American and patriotic.

Thanks for the preface Yves, increasing suicides as a consequence of economic despair have been quietly noted for decades. It’s really a no-brainer; and the European and Asian Press seem far, far more willing than the US to acknowledge this fact.

For an instance, see this PubMed study regarding the 2008 recession: 09/17/13 Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries

Looking at you Obama/Biden Administration and Wall Street.

As to male suicides outnumbering females (particularly in the US) , the reality is that females make far more attempts (serious attempts), but the ‘failed attempt’ rates for females are far higher, mostly due to the method chosen. Numerous viable links will come up searching the phrase: Women attempt suicide more than men. I suspect one main factor is in firearm ownership – particularly in the US – being far higher in males, along with mythology surrounding suicides; many are totally unaware that many attempt methods are likely to fail. Guns are one of very, very few foolproof methods.

Personally I suspect the high female suicide attempt rate is rarely discussed in the US because god knows the powers that be would never want to admit that such a Developed™ Country has yet to acknowledge that the average female, no matter the education and race, is still pathetically and criminally subjected to far more wage and job disparities than males. Consequently, females are far, far more likely to be stuck in dangerous, many times deadly (most murder suicides are committed by males), degrading, and toxic living situations due to those disparities.

Also look at Bush/Cheney Administration as well, starting a war on false pretenses that got 3000 plus Americans killed, and many others from suicides due to PTSD and the Wall Street shenanigans that led to the 2008 crash that lost people jobs and homes.

Although I will challenge guns being foolproof, maybe some guns used some ways, and for sure they fail less than many other methods. But they fail in ugly ways sometimes, and even when they are successful it is messy and can be ugly. In one of the gun suicides in my town that comes to mind the poor guy had to shoot himself in the head three times over a period of hours before he got it “right”.

I gave up on despair several decades ago.

Mostly out of contrariness, and a realization that Abraham Lincoln was right when he stated that “Most people are as happy as they make up their minds to be.”.

Some behavioral changes were necessary ( No more booze, opioids or pot to deal with pain was a start), doing volunteer work was a big part of staying emotionally positive.

Feel powerless?

Do something simple and useful for yourself or someone else.

If we change what we do , we change how we feel.

I spoke with three people today and mentioned to all of them that it was rainbow weather and that I hoped they saw one.

I looked, the sky was beautiful.

No rainbows, but plenty of beauty.

Loss of livelihood certainly can lead to isolation and despair– not even poor people want to be around poor people, it’s too damn depressing!

Very interesting data, and obviously open to interpretation given that it is correlational. There is already a fair amount of data that links death of CV19 with socio-economic status so I expect that Yves’ interpretation is more valid. But the research is worthwhile and data is useful nevertheless.

I agree with Yves. The deaths of despair discussed in the article are due LESS to isolation and more to loss of livelihood (and the prospect of a “normal” livelihood never returning).

The author of the article has never experienced that loss and likely never will. He is focused on a “first world” problem. The suicides are confronting a “third world” problem. There is a qualitative difference between the Manhattanite bemoaning the closure of the local deli and the loss of its social circle—and the unemployed, middle-aged man on the streets of Los Angeles who has lost not just his job but his career, his wife and family, his friends and neighbors and community and his stature and self-image whose biggest treat today will be finding a cardboard box that has not been pissed on.

One little point. I don’t see Hunter or the Heinz kid swooning and over-dosing. They are secure. They might not be giddy with happiness right now but basically the rich kids are not in the suicide brigade. So there is a very instructive lesson. It is not a lack of jobs, it is lack of well-being. It is frantic worry about the future. The very simple solution to this kind of despair (as opposed to the despair of a terminal illness or un-fixable thing) is to give every man/woman a check. period. end of story. Every single one. That is, a check, or now credit card (notice the expiration on your EIPC card? 2024, and extendable to 2031… really?). Along with direct sustenance payments, we should get on the airways and say bluntly and honestly declare (maybe uncle Joe and aunt Kammie, but someone with the authority to do so) that our former way of life was idiotically unsustainable and we are switching over. Everyone is taking a hit, all the way up to Wall Street. So tough luck for everyone. And your credit will be there come hell or high water. Budget accordingly. It’s not your fault – we are truly all in this together. (There’s no question about this – the only thing that can destroy trust is if the democrats screw with these payments to everyone – if they logjam the money or some other corrupt self-interested behavior for which they are infamous). If I saw that message on the tube, I’d have a beer, put my feet up, enjoy the moment and not even consider killing myself.

Most recessions (including 2009) actually result in a lower death rate. This is well-known by demographers and due to factors like lower pollution, less driving, etc. Yes, the number of suicides goes up, but other factors go down and one has to look at the whole picture.

His argument also relies on us to trust his corrections for underreporting of Covid. His charts line up fairly well with the trajectory of Covid cases. As some of the other commenters have pointed out, a breakdown by state would be more convincing.