By Lambert Strether of Corremte.

Everybody know what mud is, right? Here’s a picture[1] of mud in season from the Bangor Daily News:

The reporter writes:

Mud season in Maine, sometimes called the state’s “fifth season,” generally occurs between March and late April or early May. It happens when the snow and ice start melting. All that extra water leads to a lot of mud…. The mud is deep, the texture often seems more like Jello than hardpan and the damage it can do to your car or your peace of mind is real.

Sadly, I see I have given way to my tendency to be too optimistic about the approach of Spring — I learned to hard way never to plant before Memorial Day when two days of snowish rain rotted all the seeds I’d planted two weeks early — because Mud Season begins in towards the end of March, not the beginning. In fact, it’s still winter, at least in the Northern Hemisphere. Winter, it is said, derives from either from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) *wed, meaning “wet,” or the the PIE *wind-, meaning “white.” Spring, the 14th century “springing time,” refers to plants “springing” from the ground. Summer comes from the PIE *sam-, meaning… summer, which seems to be a variant of the Proto-Indo-European *sem- meaning “together / one,” as at barbecues, baseball games and so forth. Fall comes from falling leaves (and perhaps, I would speculate failing light). But only Mud Season comes from the soil!

Soil and water do mix. But not always completely! From the Farmer’s Almanac:

Those living in Maine and other New England states, as well as places like Colorado and Montana, know this weather better than most. That’s because mud season occurs in places like these, where the ground freezes in winter and allows large amounts of snow to accumulate and cover it all winter long. As winter wanes and air temperatures warm above freezing (32º F), the ground thaws from the surface down, triggering the snow on top of it to melt. But because the ground’s lower layers deep underground don’t warm as quickly and remain frozen, water from melting snow and chilly spring rains aren’t able to seep down very far. Instead, this water “sits” near the surface where it waterlogs the top layer of soil and creates a sea of mud—sometimes up to several inches thick!

Here, however, is a second picture of mud. From the United States Geological Service (USGS):

And the caption:

Container of mud from the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an expanse of the deep Pacific seafloor rich in manganese nodules. Amy Gartman (USGS) and Phoebe Lam (University of California, Santa Cruz) will study chemical interactions between the mud and metals in seawater.

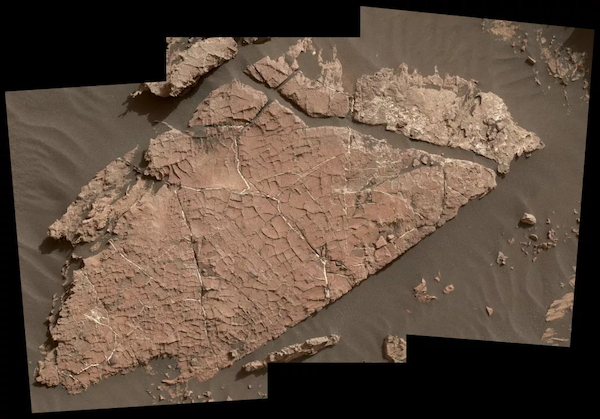

I’m not seeing a Jello texture, here. Much less here. From Space.com, “Mud Cracks on Mars Suggest a Watery Ancient Past,” a photo from the Curiosity Rover:

And the caption:

A Martian rock slab called “Old Soaker” on Mount Sharp has a network of cracks that might have formed from a mud layer that dried more than 3 billion years ago. This image was taken by the Mast Camera (Mastcam) on NASA’s Curiosity rover on Dec. 20, 2016. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

At this point, baffled by the notion of a Jello-like substance that was self-contained yet might, at some point, dry out, I started looking for a definition of mud. From my Webster’s app:

Wet, sticky, soft earth, as on the banks of a river.

Hmm. I see river banks as being muddy, but not mud; they have structure (see “Sediment, Big Spring Run, and River Restoration to Pre-Colonial Times” at NC). From my OED app:

1. Soft wet soil, sand, dust, or other earthy matter; mire, sludge. Also, hard ground produced by the drying of an area of this; colloq. soil. lme.

‣c spec. in Geology. A semi-liquid or soft and plastic mixture of finely comminuted rock particles with water; a kind of this. l19.

The OED’s sense 1 at least conveys the notion that mud by dry out and still be mud, as (possibly) on Mars; but not sense 1(c), the geologists’ definition! With a sigh, we turn to WikiPedia:

Mud is soil, loam, silt or clay mixed with water. It usually forms after rainfall or near water sources. Ancient mud deposits harden over geological time to form sedimentary rock…

Here as with the OED, we have the notion of time introduced, but according to Wikipedia’s definition, whatever Maine has in Mud Season is not in fact mud, since its water portion comes from snow- or ice-melt, not rain.

We also note, in Wikipedia’s definition, a distinct lack of footnotes; apparently there is no authoritative or science-based definition of mud to which they can cite. Can this really be true? Yes, dear reader, it can be — and this has turned out to be the point of this post, it did have one — as an examination of the work produced by two standards bodies will show.[2]

But before quoting great slabs of material on soil science from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), let me justify a focus on mud as a topic to those not already fascinated by it. From Nature in 2015:

Against such enormous societal problems, the Geological Society’s decision to focus on mud might at first elicit a snigger: mud is a problem to face with wellies, not with a global research agenda. But take a moment to consider how mud influences the world of science.

For starters, there is the entire record of the history of life. Fossils preserved in mudstone, such as the exquisite Burgess Shale high in the Canadian Rockies, reveal the story of vertebrate evolution. Without small creatures drowning in and being encased by mud, we would have a much harder time unravelling the relationship between organisms past and present.

Then there is the economic importance of mud-based rocks. Petroleum engineers have been exploring shale as a future source of both oil and natural gas. Although controversy rages about how much shale gas might ultimately be available (see Nature 516, 28–30; 2014), extraction rates have soared in the United States, driven by big reserves such as the Marcellus Shale underlying much of Pennsylvania and neighbouring states. In March, industry and academic experts will gather in London to assess the numbers behind a possible ramp-up in shale-resource production in the United Kingdom.

Finally, consider how soil and mud combine to underpin many of the globe’s natural disasters. Assessing flood risk requires knowing what soils are where, and how likely they are to turn to mud in times of heavy downpours.

The Geological Society’s “decision” mentioned by Nature was to proclaim 2015 The Year of Mud; there’s a kick-off lecture in the Appendix at the end of this post. (It describes one type of mud as having “a cauliflower-like structure erupting on the surface,” which is the sort of thing for which any definition of mud, were there to be one, would have to give an account.). Mental Floss introduced the Year, adding to Nature’s list of why mud is important and interesting:

There’s more to mud than most people realize. According to the Geological Society’s website:

Mud represents both an end and a beginning—the end of the cycle of erosion and transport, and the beginning of the generation (through burial and transformation) of new materials of great value to society.

Mud may begin as wet dirt, but it ends up in all kinds of useful places. Its texture and malleability make it a favorite building material of people all over the world. Liquid mud, or slip, is an essential component of pottery. Sedimentary rocks like shale are actually made of mud. Tourists and spa visitors pay good money to be plastered with therapeutic mud. And millions of creatures, great and small, make their homes in mud puddles, banks, and riverbeds.

So, given the importance of mud as a substance, geologically, ecologically, and economically, I’d would have expected Science (the social organism, not the magazine) to proffer a definition[3]. In fact, I’d expect a taxonomy, as with soil (see NC here). Wet vs. dry is one obvious axis of comparison. Chemical and mineral composition would be another. Water source would be a third. Duration would be a fourth. But such was not to be!

I promised I would look at two authoritative books. Here, I will quote a great slab of material from the USDA’s wonderful (PDF) “Soil Taxonomy: A Basic System of Soil Classification for Making and Interpreting Soil Surveys.”

Sidebar: I’m quoting so much partly because I just love the subject matter; but also as a mental exercise for any citizen scientists and/or activists out there. If, for example, you are fighting a permitting battle against a landfill, or a pipeline, or some other atrocity, texts like these, very much including their taxonomies and classification systems, inform the lingua franca of the science behind the permitting process as understood by the powers that be. So it’s important to master them (even, I would urge, in cases of direct action, since communication with the media and public relations generally is much enhanced by an obvious mastery of the science. Ideally you want the press calling you because you’re a subject matter expert). So becoming literate in documents like this is important. End sidebar.

From the beginning of Chapter One, “The Soils that We Classify”:

The word “soil,” like many common words, has several meanings. In its traditional meaning, soil is the natural medium for the growth of land plants, whether or not it has discernible soil horizons. This meaning is still the common understanding of the word, and the greatest interest in soil is centered on this meaning. People consider soil important because it supports plants that supply food, fibers, drugs, and other wants of humans and because it filters water and recycles wastes. Soil covers the earth’s surface as a continuum, except on bare rock, in areas of perpetual frost or deep water, or on the bare ice of glaciers. In this sense, soil has a thickness that is determined by the rooting depth of plants.

About 1870, a new concept of soil was introduced by the Russian school led by Dokuchaiev (Glinka, 1927). Soils were conceived to be independent natural bodies, each with a unique morphology resulting from a unique combination of climate, living matter, earthy parent materials, relief, and age of landforms. The morphology of each soil, as expressed by a vertical section through the differing horizons, reflects the combined effects of the particular set of genetic factors responsible for its development.

This was a revolutionary concept. … The Russian view of soils as independent natural bodies that have genetic horizons led to a concept of soil as the part of the earth’s crust that has properties reflecting the effects of local and regional soil-forming agents. Soil in this text is a natural body comprised of solids (minerals and organic matter), liquid, and gases that occurs on the land surface, occupies space, and is characterized by one or both of the following: horizons, or layers, that are distinguishable from the initial material as a result of additions, losses, transfers, and transformations of energy and matter or the ability to support rooted plants in a natural environment….

The upper limit of soil is the boundary between soil and air, shallow water, live plants, or plant materials that have not begun to decompose. Areas are not considered to have soil if the surface is permanently covered by water too deep (typically more than 2.5 m) for the growth of rooted plants. The horizontal boundaries of soil are areas where the soil grades to deep water, barren areas, rock, or ice. In some places the separation between soil and nonsoil is so gradual that clear distinctions cannot be made.

The document has no glossary, so it is perhaps not fair to ask that “mud” be defined; however, mud, as such, is not even used (we have muddy water, mudflow material, and mudflows). One would think that mud is “a natural body comprised of solids (minerals and organic matter), liquid, and gases that occurs on the land surface [and] occupies space,” but perhaps, being muddy, it lacks horizons/layers? (Can this be true when it dries?) In any case, mud is firmly refused a place in soil canon by USDA.

We turn now to the FAO’s (PDF) “World Reference Base for Soil Resources” (WRB). Again, the Introduction is magisterial. (It’s a real testimony to the power of state capacity still that such documents are available, for free, on the Internet, and not paywalled.) From the first chapter, the section titled “The object classified in the WRB”:

Like many common words, ‘soil’ has several meanings. In its traditional meaning, soil is the natural medium for the growth of plants, whether or not it has discernible soil horizons (Soil Survey Staff, 1999).

In the 1998 WRB, soil was defined as:

“… a continuous natural body which has three spatial and one temporal dimension. The three main features governing soil are:

• It is formed by mineral and organic constituents and includes solid, liquid and gaseous phases.

• The constituents are organized in structures, specific for the pedological medium. These structures form the morphological aspect of the soil cover, equivalent to the anatomy of a living being. They result from the history of the soil cover and from its actual dynamics and properties. Study of the structures of the soil cover facilitates perception of the physical, chemical and biological properties; it permits understanding the past and present of the soil, and predicting its future.

• The soil is in constant evolution, thus giving the soil its fourth dimension, time.”

Although there are good arguments to limit soil survey and mapping to identifiable stable soil areas with a certain thickness, the WRB has taken the more comprehensive approach to name any object forming part of the epiderm of the earth (Sokolov, 1997; Nachtergaele, 2005). This approach has a number of advantages; notably that it allows for the tackling environmental problems in a systematic and holistic way, and avoids sterile discussion on a universally agreed definition of soil and its required thickness and stability. Therefore, the object classified in the WRB is: any material within 2 m of the Earth’s surface that is in contact with the atmosphere, excluding living organisms, areas with continuous ice not covered by other material, and water bodies deeper than 2 m1. If explicitly stated, the object classified in the WRB includes layers deeper than 2 m.

(Yes, the “like many common words” really does occur in both sources!”) Surely, then, mud forms “part of the epiderm of the earth”? Apparently not. Here is the single reference to mud in WRB:

Terric horizon

General description

A terric horizon (from Latin terra, earth) is a mineral surface horizon that develops through addition of, for example, earthy manures, compost, beach sands, loess or mud. It may contain stones, randomly sorted and distributed. In most cases it is built up gradually over a long period of time. Occasionally, terric horizons are created by single additions of material. Normally the added material is mixed with the original topsoil.

So there you have it; once again, mud is not part of the soil canon. Mud is mentioned, but what is it? Apparently, everyone knows (even if it can form a horizon, contra USDA[3]). So no reason to define or classify it.

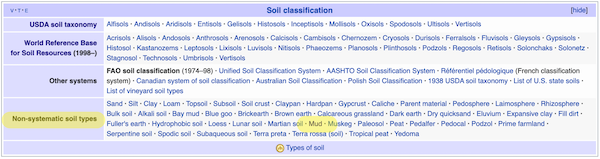

Perhaps mud is not defined or classified (at least by the two bodies, USDA and FAO) because it is seen as not amenable to definition or classification. WikiPedia has the following chart at the end of its entry on Mud:

As you can see, mud falls into the “non-systematic” section. And yet non-systematic soil types — described by “common words,” note well — are commercially important (“sand,” “clay,” “loam”), scientifically important (“Lunar soil,” “Martian soil”), and agriculturally critical (“topsoil,” “subsoil”). As we have seen, mud is important, too. It’s very odd. 66% of the rocks exposed on the earth’s surface are sedimentary, i.e., mud can play a key role in their formation[5]. And yet I can find no definition or classification system for the very substance that formed them. It’s very odd. Why?

NOTES

[1] I probably should have included videos, besides pictures. Most of the mud videos involving people are weirdly prurient, not suitable for a family blog; but there is also an entire genre of vehicles getting trapped in mud, or pulled out; here is one such. Chacun à son goût….

[2] For all I know, there’s a standard definition and taxonomy of mud types out there, and Google being what it is, I was not able to find it in the time available to me; readers please weigh in. For example, I would expect a department or institute of “Mud Studies” somewhere; but a search yields no joy. That said, the two sources I cite are at the pinnacles of this subject matter.

[3] In my travels, I saw definitions for bay mud, mud crabs, mud owls, drilling mud, and MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons (or Dimensions (or Domains))). But nothing for mud as such. See caveats in note [2].

[4] I believe this is an example of mud forming a horizon: A high-water mark. From the USGS:

The left picture shows a poison ivy vine with the bottom leaves covered in dried mud. The line where the mud stops indicated where muddy stormwater was flowing, and, thus, how high Peachtree Creek got during the storm.

And I’m quoting this part not because it is about mud, but because it is wise about methodology:

The right-side picture shows a limb that hangs over Peachtree Creek. During a flood, rapidly-moving water carries leaves, straw, and even whole trees! Wet leaves get stuck on limbs that are partially submerged in the stream. When the stream recedes the leaves remain on the limbs. The top of the leaves and pine straw indicate how high Peachtree Creek was during the storm.

The mud on the poison ivy vine [above] is a much better high-water mark than the tree limb, though. During high water, part of the tree limb will be submerged in the fast-moving water, which will cause it to move up and down. Hydrologists would not use this type of high-water mark to estimate peak stream stage during a flood.

[5] From the USGS, “What Are Sedimentary Rocks?”:

Clastic sedimentary rocks are the group of rocks most people think of when they think of sedimentary rocks. Clastic sedimentary rocks are made up of pieces (clasts) of pre-existing rocks. Pieces of rock are loosened by weathering, then transported to some basin or depression where sediment is trapped. If the sediment is buried deeply, it becomes compacted and cemented, forming sedimentary rock. Clastic sedimentary rocks may have particles ranging in size from microscopic clay to huge boulders. Their names are based on their clast or grain size. The smallest grains are called clay, then silt, then sand. Grains larger than 2 millimeters are called pebbles. Shale is a rock made mostly of clay, siltstone is made up of silt-sized grains, sandstone is made of sand-sized clasts, and conglomerate is made of pebbles surrounded by a matrix of sand or mud.

APPENDIX

Here is a lecture given by David Manning, Chair in Soil Science at Newcastle University, given as part of 2015’s Year of Mud:

I was multitasking while I listened to it, but if Manning defines mud, or introduces a classification system, I missed it. It was still extremely interesting, and I think soil fans will enjoy it.

Of course mud has had an effect on military operations throughout the ages and most people would be familiar with the mud of WW1. But the first that came to mind was the battle of Waterloo in 1815 – Napoleon’s last battle. It rained heavily the night before and so Napoleon was not able to properly deploy his forces,especially his artillery, so was forced to wait several hours until the ground dried sufficiently and so the first attack did not begin till nearly midday.

This gave time for the German troops under Blücher to finally join up with the British troops and crush the French. But they did not do so until the near end of the day. The reason why? Because they too had to fight the mud to get to the battlefield. I have a sample of the soil from Waterloo and it looks a lot like the dirt at my place. When dry it is almost a powder but when turned to mud is something to be avoided. Too many examples to think of the effect of mud and warfare but it is never to be dismissed.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rasputitsa

Mud, Mud, Glorious Mud!

in Just-

spring when the world is mud-

luscious. . . .

and words of

that ilk

Hey, even more so the battle of Agincourt.

The very short version is the English were seriously outmanned, and the French had heavy horse.

English were 80% longbowmen. Found a spot where the terrain forced a narrow-ish approach (woods on both sides). English had longbowmen on both flanks, men at arms and horsemen in the center.

The French regarded the encounter as a probably romp. Noblemen in armor on horses heavily represented, in the vanguard and main army.

The field of battle was a sea of mud. French horses became mired and if they fell over, could not rise again due to the bad footing and the weight of their armor. So it became a melee, fallen horses and men blocking French advance and retreat, English longbowmen picking them off before their swordmen came in to finish off more.

Soil turns to mud when water is above the field capacity, which is the water has filled all the pores and saturated the particles. At some point soon after that I think it must become a state of water rather than soil. Compaction reduces soil capacity so if you drive over wet soil you make mud…

http://www.terragis.bees.unsw.edu.au/terraGIS_soil/sp_water-soil_moisture_classification.html

I guess spring is right around the corner…

Working geologist here! I agree that there isn’t a specific geological definition of mud.

I classify material as “mud” only:

1. when it is both saturated and lacking enough cohesion to identify the suspended fine material, and

2. when I don’t have to perform additional tests to identify the stuff (using stokes law, Atterberg limits, etc.).

In layman’s terms, when a mixed, goopy material of a consistency ranging from cake batter to soup needs to be described for identification in the field, it’s mud or muddy. As soon as I can identify what is the component that is making the goop- which is almost always clay or silt, it’s no longer mud.

If I see something muddy, but I can identify that it’s silt (picture a geologist “eating” the stuff- silt abrades your teeth, clay does not, bone sticks to your tongue), it’s now silty instead of muddy. Clay? it’s clayey. etc. Then there’s the chemistry of the material- a carbonate mud, a sulfate mud, organic/peaty mud, etc. that can be narrowed down by size (q.v.), etc.

I hope that’s as clear as mud.

geologists eating the stuff – that reminded me of a recent Infinite Monkey Cage episode, A history of rock, where the two invited geologists talk just of that and Cox tells “kids, don’t try that at home”. The difference between field science and in-your-office (when not staring-at-stars-dreamily) theoretical physicist.

> a mixed, goopy material of a consistency ranging from cake batter to soup

I recently encountered the term “gloopage.”

It’s a dense colloidal suspension.

Psychologically speaking, Lambert, but also somewhat scientifically (by my measure) I much prefer having spring begin the day after the winter solstice. It works out here in New Mexico because my crocuses optimistically follow my calendar and start upcoming in January, sometimes even the early part of the month. Call me crazy (it’s okay, many do) but that’s the light factor I think all plants figure into their own calculations, even if what they do has to wait for the climate to catch up to the sun. The roots are stirring…sending messages…

For sure, I don’t plant outside then, but also for sure, I have milk cartons saved to cut to size and dirt in tubs that can come inside and thaw out — and windowsills to put early greens and other cold lovers onto. (Peas for instance.) And later on, indoor planters by the south facing floor to ceiling windows. (Sorry if you don’t have any of those, but you do have windowsills. ) And if you have cats, staple on some of that netting lots of veggies come in onto your greens cartons – or put them up out of catreach somehow. It helps convince you that yes, it really is spring!

And yes, cold keeps on coming, but hey, it’s fighting a losing battle. So is mud. Hang in there!

I think looking for mud in science taxonomies is kind of like looking for the word “tummy” in anatomy texts. People who describe soil, dirt, and unconsolidated sediments call the stuff clay. Your northern spring plague is oversaturated clay and clayey soil. That said, sympathies, and I hope spring buds are not too long in arriving!

So perhaps mudness is an attribute or a quality rather than mud being a thing, technically speaking.

Though there are some particular things referred to as “drilling mud” in a very specific way.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/drilling-mud

Mud season! What fun

In the snow-tired beater on a run

Sliding round the corners

Slooping tween the ruts

Oh jeez the mufflers dragging

We’ll wake up the McNutts!

Thank you for this reminder of spring, which I read a couple of hours after shoveling off the latest 15 cm of new snow from my central British Columbia driveway. Earlier this weekend, I had taken my annual leap of faith, and had sown my first seeds under the grow-lights on my kitchen table: 2 kinds of leeks, and a dozen precious New Mexico pepper varieties.

As a soil scientist, I don’t mind leaving “mud” as an imprecise folk term, because despite that, everyone seems to know what is is!

Digression: The various tribes of earth scientists often use their own separate terms for the same phenomena, and I’m sure that this silo behaviour exasperates laypersons. And when the same word exists as both a folk term and something with a formal scientific meaning, there is potential for further confusion and perhaps friction. As you showed in your comprehensive soils round-up (Dec 22 2019), “loam” and its neighbours (“silt loam”, “sandy loam” etc.) have specific definitions as displayed in the soil texture triangle. Of course, “loam” is a well-established folk term which doesn’t imply quite so definite a composition. But when I use the l-word when I’m chatting with my colleague the surficial geologist, he invariably looks at me with a mixture of bafflement and annoyance. (So when his students take my pedology course, I get them to promise that they will sprinkle this word into their conversation when he’s within earshot. That’s how I know that my life has not been wasted.)

The geology tribe seem to use the m-word in combination with their r-word. The online glossary provided by oil industry service firm Schlumberger gives this definition of “mudrock”:

“A fine-grained detrital sedimentary rock formed by consolidation of clay- and silt-sized particles. Mudrocks are highly variable in their clay content and are often rich in carbonate material. As a consequence, they are less fissile, or susceptible to splitting along planes, than shales. Mudrocks may include relatively large amounts of organic material compared with other rock types and thus have potential to become rich hydrocarbon source rocks. The typical fine grain size and low permeability, a consequence of the alignment of their platy or flaky grains, allow mudrocks to form good cap rocks for hydrocarbon traps. However, mudrocks are also capable of being reservoir rocks, as evidenced by the many wells drilled into them to produce gas.” https://www.glossary.oilfield.slb.com/en/Terms/m/mudrock.aspx

And no less than Science itself had a recent special issue devoted to an eclectic set of case studies united by the common theme of mud (Aug 21 2020). From the introductory article:

“Mire. Ooze. Cohesive sediment. Call it what you want, mud—a mixture of fine sediment and water—is one of the most common and consequential substances on Earth. Not quite a solid, not quite a liquid, mud coats the bottoms of our lakes, rivers, and seas. It helps form massive floodplains, river deltas, and tidal flats that store vast quantities of carbon and nutrients, and support vibrant communities of people, flora, and fauna. This special collection of stories and graphics explores the world of mud, and how humans have become a dominant force in how mud forms and is distributed. Stories examine how, centuries ago, mud released by colonial farming and logging buried streams, and how modern industrial activities have created vast ponds of polluted mud—from mining waste and aluminum production—that can pose serious threats to human and natural communities. And they explore what biologists are learning about organisms that live in mud, including extraordinary bacteria that conduct electricity in order to survive in oxygen-poor sediments. And a graphic looks at how sediment flows are changing globally, with sometimes dramatic implications for rivers and coastlines.” https://science.sciencemag.org/content/369/6506/894.summary

Mud is fascinating. I became aware of just how variable it could be when a few years back I regularly mountain biked a trail loop near my home – the area had a thin loamy soil over deep clean glacial deposits, so was generally dry when it wasn’t raining, except when it was super wet and the groundwater pushed from below. Riding the identical trail year round and having to scrape that mud off the vulnerable bits of the bike (and me) showed just how variable it could be despite the homogenous geology. The mud after a short rainfall in summer was very different from the same mud a day after a period of wet weather – it seems to change consistency and stickiness and even smell according to the season and weather.

As to your point about citizen science and landfills is well taken too. Even professional geologists sometimes assume clay layers are uniformly impermeable (or at least, those employed by landfill operators do), when in reality they can be quite heterogenous and hard to classify, and you certainly cannot assume they are watertight. This is particularly so with the muddy layers deposited in glacial moraines.

I live on a ridgetop caked in what we call ‘tectonic toothpaste,’ rock pulverized by the San Andreas fault grinding into the Cascadia subduction zone nearby. The consequent clay we call ‘blue goo.’ And it’s so platey (thanks for the word!) that it sheds water horizontally rather than vertically. My little pond bleeds mucho moisture sideways out hillsides, but never dries.

Also, the Midwest has Mud seasonettes all winter, from the constant combat between Alaskan and Gulf weather systems meeting in mid-continent. The rest of the year they’re good for tornadoes. So I chose earthquakes.

> Even professional geologists sometimes assume clay layers are uniformly impermeable (or at least, those employed by landfill operators do),

All landfill liners fail!!

“how modern industrial activities have created vast ponds of polluted mud—from mining waste and aluminum production—that can pose serious threats to human and natural communities. And they explore what biologists are learning about organisms that live in mud, including extraordinary bacteria that conduct electricity in order to survive in oxygen-poor sediments.”

***************

The fill to form the basis for roads around here in my rural area was all trucked in from elsewhere. This includes both hardtop and dirt roads. On top of those roads are loads of toxic material. First from the road construction itself and then from the road use: the asphalt itself, then the toxic fluids dripping from the vehicles and also tire dust. The more abrasive the road, the more tire dust. There is also the settling pollution from the vehicles’ exhaust.

So, roads are really just vast long lines of pollution and health hazard. As for the “organisms that live in [that] mud” or near those roads, good luck.

to your point:

For decades, something in urban streams has been killing coho salmon in the U.S. Pacific Northwest.

https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/12/common-tire-chemical-implicated-mysterious-deaths-risk-salmon

Making me think of the band Mudhoney.

Their song “Here Comes Sickness” fits well for the times…

https://youtu.be/J6h1Rs83VuY

Looking towards mud season here in N. Michigan. Luckily the soils left by the glaciers drain well, but need fortifying in order to garden. The fine grained clays in some areas still make some back roads slippery and muddy. On par with mud season is the season of spring allergies from all the mold breaking down all the last year’s vegetation accumulated on the forest floor.

Thank you for pointing out the exceptional preservation of animals in the Burgess Shale. The fauna is incredible, and for a glimpse of this S. J. Gould wrote a very readable book, Wonderful Life.

I have had the fortune to travel with geologists to the Anti-Atlas of Morocco where one site we visited was the Fezouta Shale. Burgess-like, in soft tissue preservation, but from a younger period, we were able to meet a family of collectors and preparators who work at that site.

Now, as the snow melts and mud season starts

As they kept Spring, Summer and Winter I wonder why Americans adopted ‘Fall’ instead of retaining the “Autumn” of most of the rest of the English-speaking world.

Sure leaves ‘fall’ in the Autumn particularly in the mostly deciduous NE States, but not universally. So perhaps it’s a reference to the sun appearing to fall in the sky as it declines to the south.

According to Etymonline.com “Harvest” was the English name for the season until the C16th when the French automne from Latin autumnus began to be adopted, which means ‘Harvest’ for the season would have been familiar to the first settlers in the US. And given the central importance of the harvest to all agricultural societies it seems strange that the US should break with it.

According to the OED:

Sense of “autumn” (now only in U.S. but formerly common in England) is by 1660s, short for fall of the leaf (1540s).

About names for seasons, Kurt Vonnegut suggested the Midwest should have two extra names for the two extra seasons we have. The time between Fall and Winter when water bodies/ soil/etc. begin fitfully freezing and de-freezing before winter freezes them for good. And the time between winter and spring when frozen water and soil begin fitfully de-freezing and re-freezing until spring melts them all down for good.

Since Vonnegut was too poetic, he wanted to call these two transition-seasons ” locking” and ” un-locking”.

I would rather call them freeze-up and breakup.

So . . . spring, summer, fall, freeze-up, winter, breakup, spring.