By Lambert Strether of Corrente

I wish I could be doing a cheerful perambulation through soil taxonomies (again), but today I want to focus, at a high level, on two escalating problems with soil: The degradation of our (the world’s) topsoil, important because that’s where grow our food, at least so far; and the loss of soil as such, due to erosion (we just looked at the effects of erosion on river systems in considering sediment). The press seems to have addressed topsoil first, a couple of years ago, and then, this year, science has gone on to erosion. I will then avoid a deep dive, or indeed any kind of dive at all, into technical solutions for soil issues (for example, no-till, regenerative agriculture, sustainable practices, soil health, or recarbonization), and look at briefly at “governance” issues instead. Paradoxically, soil is both a private asset and a public good; institutionally, we do not seem to have been able to address or even approach this contradiction.[1]

Topsoil Degradation (and the “60 Harvests” Figure)

What is topsoil? In a previous post, we presented this definition:

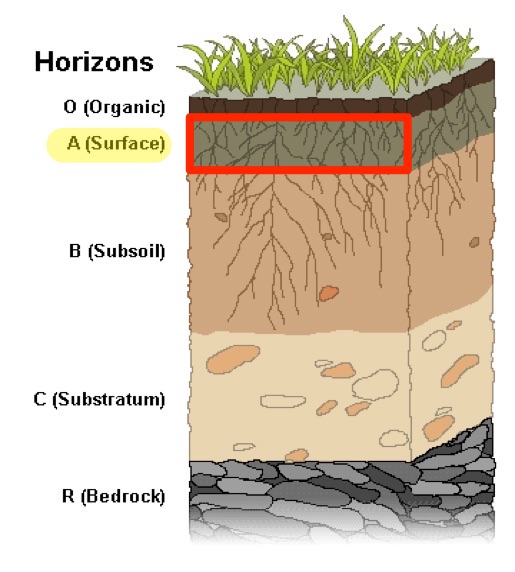

A: This upper soil horizon is also called Topsoil. It is only between 5 to 10 inches thick and consists of organic matter and minerals. This is the soil layer where plants and organisms primarily live.

And this chart (here modified):

Unfortunately, topsoil is degrading. From the Guardian, “The world needs topsoil to grow 95% of its food – but it’s rapidly disappearing“, May 2019:

The world grows 95% of its food in the uppermost layer of soil, making topsoil one of the most important components of our food system. But thanks to conventional farming practices, nearly half of the most productive soil has disappeared in the world in the last 150 years, threatening crop yields and contributing to nutrient pollution, dead zones and erosion. In the US alone, soil on cropland is eroding 10 times faster than it can be replenished.

If we continue to degrade the soil at the rate we are now, the world could run out of topsoil in about 60 years according to Maria-Helena Semedo of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization.Without topsoil, the earth’s ability to filter water, absorb carbon, and feed people plunges. Not only that, but the food we do grow will probably be lower in vital nutrients.

The modern combination of intensive tilling, lack of cover crops, synthetic fertilizers and pesticide use has left farmland stripped of the nutrients, minerals and microbes that support healthy plant life[2].

60 years (at least in the United States) would 60 harvests. That’s not very many. For many of us, the endpoint would come not in our grandchildrens’ lives, but in our childrens’. It would also be a really good idea to have stopped degrading the soil some time ago. Scientific American:

Generating three centimeters [1.18 inches] of top soil takes 1,000 years.

Having rung the alarm bell, let me now at least muffle it. From the New Scientist, “The idea that there are only 100 harvests left is just a fantasy,” from 2019:

While some report that we have 100 years until the end of our soil’s ability to support farming, citing a University of Sheffield study, others claim that this is a mere 60 years away, referencing a speech at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization.

… Despite dozens of headlines quoting these predictions, surprisingly only one peer-reviewed paper from a scientific journal is ever cited as evidence to back them up. This 2014 study from the University of Sheffield compared the soil quality of a range of sites in the English city, including agricultural, garden and allotment soils…. [B]ut where is the 100-year statistic? It turns out that nowhere in the study was there any calculation, prediction or even passing reference to the claim. None whatsoever. Perhaps not so much shaky evidence to support this assertion as much as non-existent.

Maybe this is the result of a typo and the work is in another research paper? After an 8-hour trawl through the academic journals failed to pull up a single study that even attempted to make this calculation, I contacted six leading soil scientists across the world to ask if they had ever come across such a prediction in either the published literature or their work. Not a single one had.

In fact, the words they used to describe this claim were “bold”, “too Malthusian”, “hardly useful”, “almost insulting” and “I have used this in my soil science lectures to show the students to be wary of headlines!”. Ouch.

Does that mean there aren’t real threats to some agricultural soils around the world? Absolutely not. Indeed, all the scientists I spoke to went to great lengths to point these out, where they exist.

However, they also highlighted how incredibly complex the calculations needed to make such predictions would be, based on myriad factors, only some of which can be predicted with any reliability, with generalisations almost impossible…. Despite the thirst for simple truths in a complicated world, the researchers I contacted agreed that setting such a figure for an agricultural “end-point” would be nigh on impossible, which may explain why no published studies appear to have been able to do so.

(One might speculate that the UN’s exaggeration and headline-seeking was driven by institutional weakness.) I will have more to say under “Soils and Governance” about agricultural endpoints (which I, unlike Wong, believe are real, regardless of the spurious precision of “60 years.”)

Soil Erosion

Now let’s look at soil erosion, where we have a major new study in PNAS, “Land use and climate change impacts on global soil erosion by water (2015-2070),” published on September 8. First, an overview on erosion (footnotes omitted):

Contemporary societies live on a cultivated planet where agriculture covers ∼38% of the land surface. Humans strongly depend on the capacity of soils to sustain agricultural production and livestock, which contributes more than 95% of global food production. The underlying agricultural systems are at the same time major drivers of soil and environmental degradation and a substantial source of major biogenic greenhouse gas emissions. The latest United Nations (UN) report on the status of global soil resources highlights that ‘…the majority of the world’s soil resources are in only fair, poor, or very poor condition’ and stresses that soil erosion is still a major environmental and agricultural threat worldwide. Ploughing, unsuitable agricultural practices, combined with deforestation and overgrazing, are the main causes of human-induced soil erosion. This triggers a series of cascading effects within the ecosystem such as nutrient loss, reduced carbon storage, declining biodiversity, and soil and ecosystem stability.

And now methodological issues (reinforcing Wang’s remark above on “how incredibly complex the calculations needed to make such predictions would be”):

Modeling soil erosion at global scales is challenging, physical models are too data intensive and the data are sparse, therefore adopting a semiempirical approach represents the state of knowledge and a pragmatic approach to informing policy. Only two studies have been successful at attempting future global soil erosion estimates, both at coarse scale (∼50 km or greater), using old climate projections and hence, impractical for policy making intervention…. Since [Yang and Ito’s] efforts, substantial progress has been made, both in terms of land use and climate projection. Recent advancements in remote sensing, wider availability of earth observation data, and increased processing of big datasets have enabled the development of new global vegetation indices and land cover products with both higher spatial resolution and accuracy… The same goes for the recent release of climate datasets, including bias-corrected climate projections of multiple bioclimatic variables, which through robust spatial interpolation methods allow computation of global estimates of rainfall erosivity, more closely related to rainfall intensity than rainfall volume.

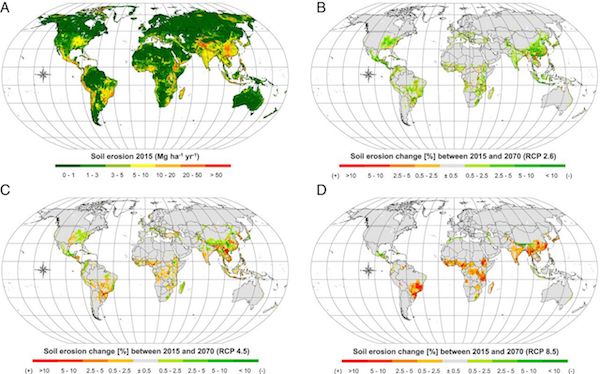

And the results, from the abstract. Three scenarios are considered:

Here we predict future rates of erosion by modeling change in potential global soil erosion by water using three alternative (2.6, 4.5, and 8.5) Shared Socioeconomic Pathway and Representative Concentration Pathway (SSP-RCP) scenarios. … Our future scenarios suggest that socioeconomic developments impacting land use will either decrease (SSP1-RCP2.6–10%) or increase (SSP2-RCP4.5 +2%, SSP5-RCP8.5 +10%) water erosion by 2070. Climate projections, for all global dynamics scenarios, indicate a trend, moving toward a more vigorous hydrological cycle, which could increase global water erosion (+30 to +66%).

Here is a map that includes the most recent data (2015) and all three scenarios:

You will notice that the American Midwest is hit in scenarios B and C (important when we discuss Iowa below). Summing up:

The multiscenario comparison suggests that although future land use changes can notably affect global soil erosion processes through the expansion or contraction of croplands, a global climate potentially moving toward more vigorous hydrological cycles would be acting as a major driver of future increases in soil erosion.

Soil and Governance

Sol is simultaneously a public and private good. From Dr. Anna Krzywoszynska of the Soil Alliance, in “Soil: Private Asset or Public Good?“:

On the one hand, farmers sometimes describe soil as their ‘factory floor’, their ‘key asset’, and their private concern. On the other, soil is a vital factor in the bio-geo-chemical cycles which maintain life on the planet, and through these to the provision of for example drinking water and breathable air, making it a public good, and so a public concern.

And from the Sustainable Soils Alliance, “The Economics of Soil: Private Asset or Public Good?”

80% of the costs associated with degraded soils occur off-site and so are either invisible or of limited concern to those whose actions may be causing them. Professor Morris described a fundamental ‘disconnect’ between the way soils are used and the broader consequences for society and the economy.

On a similar note, Guy Thompson of En Trade explained that land managers don’t know the value of the environmental services they have to offer from their land and government doesn’t understand land’s potential. The lack of mechanisms to measure and demonstrate this and so align incentives accordingly represents a market failure and failure of soil governance, and therefore justification for government intervention.

Very well. So, if soil is a public concern, and government intervention is justified to protect it, in what forum are such concerns to be addressed, and what form does intervention take? We might look to international agencies, like the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). From their page on “Soil Governance“:

Policies and strategies

Soil governance concerns policies and strategies and the processes of decision-making by nation states and local governments on how the soil is utilized.

What is the governance of soils about?

Governing the soil requires international and national collaboration between governments, local authorities, industries and citizens to ensure implementation of coherent policies that encourage practices and methodologies that regulate the usage of the soil resource to avoid degradation and conflict between users.

Needless to say, this “governance” isn’t worthy of the name[3] (though FAO does a lot of worthy technical work, as for example on locusts). Soil is not addressed as a public good common to all stakeholders (hardly to be expected, since the UN has no monopoly on violence, unlike States). So we turn to the national level, using the state of Iowa, in the United States, as a miniature case study. First, we’ll look at Iowa’s soil, and establish that there is indeed an “endpoint” (contra Wang). Then, we’ll look at the governance structures that control and impact Iowa’s soil.

Iowa “produces one-eleventh of the nations’ food supply and is the largest producer of corn, pork and eggs, and second in soybeans in the United States.” Iowa’s soil is prairie soil. It is classified — yes, there is a classification system from the USDA — as a “mollisol”:

Mollisols (from Latin mollis, “soft”) are the soils of grassland ecosystems. They are characterized by a thick, dark surface horizon [Layer A in the diagram of topsoil above]. This fertile surface horizon, known as a mollic epipedon, results from the long-term addition of organic materials derived from plant roots. Mollisols are among some of the most important and productive agricultural soils in the world and are extensively used for this purpose….

Mollisols primarily occur in the middle latitudes and are extensive in prairie regions such as the Great Plains of the U.S. Globally, they occupy approximately 7.0 percent of the ice-free land area. In the U.S., they are the most extensive soil order, accounting for approximately 21.5 percent of the land area.

You will recall that topsoil is typically between 5 to 10 inches deep. Mollisol is (or was) between 23 and 31 inches (60 to 80 cms). However, Iowa’s mollisol is getting thinner and thinner. From Iowa PBS :

When Iowa land was first plowed, the settlers found 14 to 16 inches of topsoil. By 2000 the average was six to eight inches. When the prairie plants were plowed under, the soil was to exposed and vulnerable to erosion. Soil erosion is the process of removing soil materials from their original sites by water or wind. Hard rains that wash across bare soil move Iowa’s black gold into gullies and streams. During dry weather winds can carry loose soil across the countryside. If nothing is done to stop the erosion, the rest of Iowa’s topsoil could be gone in the next 100 to 150 years.

So there’s your endpoint: 8 inches per century means 0 by 2100 (and faster if the degradation is worse). No more mollisol[4].

So what is the governance structure for soil in Iowa? We do have plenty of individual (i.e., private) effort. From Civil Eats:

Guthrie had help from the Iowa State University (ISU) STRIPS (Science-based Trials of Row-crops Integrated with Prairie Strips) program, which was founded in 2003 by scientists hoping study the effects of strategically planted native prairie for soil, water, and biodiversity benefits on farms. After 10 years, the team began to publish a series of papers laying out their results. They found that adding a prairie to a small fraction of a farm yields impressive benefits for water quality and nutrient retention, reducing erosion, providing habitat, and other benefits. In the years since, the ISU team has been working to help more farmers create native prairies.[5]

We have technical assistance, again adopted on an individual (i.e., private) basis:

As farmers and natural resource managers use the Daily Erosion Project to visualize erosion across space and time, the urgency of soil conservation is brought to focus.

And of course, we have good individuals trying to do the right thing (again, privately):

But over the past 17 years, Wolf’s relationship with the land has changed. No longer is the Miles farm simply a land investment.

Now, she sees the land as a part of nature, and makes decisions about her farm accordingly. Wolf introduced buffer strips to control soil runoff; developed a wetland to collect rain runoff and invite migratory birds; prioritized pasture maintenance; and began to restore a stream bank.

Her farm, in Jackson County three miles from the Mississippi River, is vulnerable to topsoil erosion. All of the measures she’s taken were with an understanding of the hilly landscape’s fragility and an acceptance that, without soil, food cannot be produced.

But Wolf’s practices are in many ways an exception to the rule when it comes to Iowa farms.

However, here’s how soil governance in Iowa really works. From Iowa PBS:

Twenty-three million acres — some 75 percent of Iowa’s farmland — is used to grow corn and soybeans, most all of it through what’s known as industrial agriculture, using expensive equipment and a massive amount of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Those two crops are highly subsidized by the federal government, to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars a year. And corn and soy are mostly grown to produce ethanol and animal feed. The remainder that’s eaten by humans is mostly in the form of junk food.

Hard to see much concern for the public good here. I selected Iowa as a case study not only because it’s losing its topsoil, and in at least two scenarios will be subject to global water erosion, but because it enjoys disproportionate political influence as our first-in-the-nation primary (or caucus) election. Quoting from Iowa Starting Line, which covers such matters, in “Iowa’s ‘Black Gold’ Is Washing Away“:

Republicans love to brag that they are the true conservatives. How can these self-proclaimed conservatives refuse to acknowledge the disappearance of Iowa’s greatest natural resource? Safeguarding Iowa’s soil should be priority number one for anyone that claims to be a conservative.

Iowa Democrats have advanced a number of proposals to address Iowa’s soil loss and water pollution. In 2016, Senator Joe Bolkcom offered a check-off solution to provide the needed funds.

“Let’s use the voluntary check-off approach that corn and soybean growers, pork, cattle, poultry and egg producers already use to generate tens of millions annually to support their marketing and research plans,” said Bolkcom. In addition, Iowa Democrats have pushed for other funding proposals for conservation measures. They have repeatedly called for funding the voter approved Natural Resources Trust Fund. Republicans refuse to listen to the 63% of Iowans that voted to approve that conservation measure.

As you can see, treating soil as a public good as well as a private asset — let alone instead of a private asset — just isn’t on the radar for either party. At all. In 2016 — and, so far as I know, 2020 — the issue hasn’t even come up (not even “green payments,” which again preserve paradigm that land, hence soil, is a private asset only). The irony here is that Iowa’s civic institutions do not seem to me to be particularly weak. Yet as the soil that is the basis of their prosperity erodes beneath their feet, they cannot see soil as the public good it is. I wish I could come to a happier conclusion, but we are where we are. Il faut cultiver notre jardin..

Conclusion

Nature has recently published “A recipe to reverse the loss of nature“, another modeling exercise. It’s not about soil per se, but about biodiversity:

By nature, we mean the diversity of life that has evolved over billions of years to exist in dynamic balance with Earth’s biophysical environment and the ecosystems present. Nature contributes to human well-being in many ways, and the services [“Nature As A Service”?] it provides, such as carbon sequestration by plants or pollination by insects, could impose a vast cost if lost.

Here too the issue is not “the science,” but governance:

Although the models say that a better future is possible, is the combination of the multiple ambitious conservation and food-system interventions considered by Leclère et al. a realistic possibility? Achieving each one of the conservation and food-system actions would require a monumental coordinated effort from all nations. And even if the global community were to get its act together in prioritizing conservation and food-system transformation, would such efforts come in time and be enough to save our planet’s natural legacy? We certainly hope so.

What would “the global community” getting “its act together” look like, operationally? I don’t think anyone knows.

NOTES

[1] For all I know, some anthropologist or field economist has given the lie to this claim, something I would very much like to have happened. Readers?

[2] When I still thought this was going to be a cheerful perambulation post, I collected a lot of great links on the wondrous complexity of soil. In no particular order: Microbial diversity, microfauna, “uninhabited surface soil environments” in Antarctica, “the contentious nature of soil organic matter,” hidden webs of fungi, and so forth. The extraordinary and wild systemic profusion, for me — speaking intuitively and tendentiously — seems to call into question the very notion of “ecoystem services” which seems more appropriate for generating dollar figures for grant proposals than anything else (“We find that, so far, the economic valuation of soil-based ecosystem services has covered only a small number of such services and most studies have employed cost-based methods rather than state-of-the-art preference-based valuation methods, even though the latter would better acknowledge the public good character of soil related services. Therefore, the relevance of existing valuation studies for political processes is low.”) magine “body services” as a concept in medicine, for example [shudder].

[3] Here is U-North Bayer using its participation in the FAO’s “Global Soil Partnership” as a public relations scheme.

[4] Hilariously, one suggestion is to “save the phenomena” of mollisol by changing the criteria for classifying it so that Iowa retains the name, mollisol, if no longer the substance: “[U]nder the principle of following the genetic thread to classify soils, the taxonomic system should be modified to accommodate the eroded units that have the same genetic pathway as their uneroded counterparts. This could be accomplished by placing primary emphasis on the organic carbon content and waiving the color requirement [“black”] for eroded soil map.”

[5] From the same source: “When farmer Gary Guthrie describes recent changes to his farm, his eyes light up. After adding native prairie to his central Iowa operation, he remembers hearing the hum of pollinators flocking to the property. ‘Oh, my goodness, it was stunning, the level of buzzing,’ Guthrie said. ‘That moment was sort of an awakening for me.’ The presence of so many bees and other insects was an indicator, to Guthrie, of the health of the land.” I honestly think that the presence of beauty is a really good sign that matters. After all, if sensing beauty were not adaptive, we wouldn’t have developed the ability to do it, would we? (Perhaps — now speculating freely — just as plants, as Michael Pollan shows in The Botany of Desire, evolve to both appeal to and shape human desire, why would not the natural landscape?

Re: “After all, if sensing beauty were not adaptive, we wouldn’t have developed the ability to do it……”

I rescued two abandoned red shaver hens at the beginning of NZ’s covid lockdown. I taught them to roost in a sheltered tree at night. They spend their days scratching/fossiking around my front and back yard.

Seeing red hens perched on a tree branch… Listening to their happy clucking as the sun rises…and seeing their good/ tireless work improving my topsoil. Beauty

I thought this was rather remarkable–not that I necessarily understand it, but just the thought that someone has been working on this for over a decade was fascinating:

Nanoclay: the liquid turning desert to farmland

https://www.bbc.com/future/bespoke/follow-the-food/the-spray-that-turns-deserts-into-farmland.html

I don’t know the science behind that, but it looks interesting.

It reminds me of how the Aran Islanders in Ireland used to make soil on bare rock. The islands – and other areas on the west coast in Ireland, are bare karstic limestone (its still argued as to whether this is natural or the result of neolithic over-farming and tree clearance). Farmers would painstakingly gather sand and seaweed from the coast, wash it clean of salt, and haul it by hand to spread on the land. Any existing topsoil was spread as thin as possible over this as a base – this would then be used for potato cropping, and later flattened for grass. There is still very healthy soils on most of those area (often now abandoned and scrubbing over). Those areas that are grazed have wonderfully diverse meadows.

There are lots of ethnographic accounts of how they made soil this way, although so far as I know there has been little scientific research into its properties. But its certainly true that what was bare rock became soil capable of maintaining extraordinary high densities of population – similar to those in the fertile paddy lands of China, Japan or Vietnam. Up until the potato crop failed of course.

I have to rush off to work in a few minutes, but at first glance this looks fascinating and promising. This would be an example of intelligent sensitive people growing topsoil faster than that Scientific American article consigned us to by the processes of callous fate as that article understood it to be.

Book: https://www.timelessfood.com/lentil-underground/

Very good — on movement to save the soil while simultaneously feeding people.

So get out there and do something about it!

Build the biggest compost heap you can of whatever material you have available and never, ever, let organic material leave your garden. Your kitchen waste and clean hardwood only fireplace ash, grass clippings, green plant material, dry leaves, twigs and small sticks. Mix it up and throw a little of your best garden soil in to help innoculate the pile.

People actually pay to have this material hauled away?

Decent instructional site:

https://www.saga.co.uk/magazine/home-garden/gardening/advice-tips/soil-improvement/how-to-make-a-compost-heap

Individuals should so their part, but individual action is not enough.

He mentions Henry George’s land tax as a policy option to save the planet. This is 2019 in Britain.

What governments can do and can’t do.

https://youtu.be/QPqhebuf2dM

I’ve cued it to start at around 36:20 HG around 42 mins in.

I think the whole talk is really interesting, and his ideas have reached far and wide.

“Generating three centimeters [1.18 inches] of top soil takes 1,000 years.” Maybe the UN thinks this, but it’s being proven wrong daily on farms worldwide.

I follow regen ag and have discovered that it’s moving much more quickly than city folk may imagine. Dennis Liu, Elaine Ingham, Ray Archuleta, Gabe Brown, Gail Fuller, Charles Massey, Walter Jehne, The Weathermakers, Neal Spackman, Nicole Masters, Charles Massy and many, many more.

The NRCS (part of USDA) has a lot of good resources. They still need to up their game on things like terra preta, but on the whole are very good. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/site/national/home/

Individuals doing their part could see eachother doing their part, and learn from/with eachother how to do their part better, and evolve into a coherent culture-load of people who can then grow and support a multi-individual movement to force the political-economic system to make beneficial changes at the system level.

That is one beneficial outcome of individuals doing their part I don’t see acknowledged often enough.

America needed a Black Church before America could have a Black Church-Based Civil Rights Revolution Movement.

Right now, nearly half of Iowa is in a severe drought. I can only imagine what Iowa will be like with a combination of a severe drought and no topsoil. I guess something like a wasteland with abandoned towns and maybe even cities. No idea of how people are going to be fed though with only limited top soils in the world. Right now we see conflicts based on water wars like with Israel and India. Perhaps by the end of the century we will see war based on fighting over topsoil. Actually, I saw a glimpse of this years ago. When Israel invaded Lebanon, before they were forced out they sent in a fleet of trucks to steal as much top soil from farms as possible to take back to Israel. No, I am not making this up. I saw the film footage. Here is a link about Iowa’s drought by the way-

https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/weather/2020/08/20/usda-seven-more-iowa-counties-severe-drought/5614898002/

A link to that footage would be good, if there is one. I would like to know that was a real event provably documented before I think about something that potentially nasty.

I remember a Russiakrainian Jewish emigrant friend of mine from the USSR (when his family left it) telling me about how the Germans dug up and sent entire trainloads of soil from Ukraine back to Germany during the WWII time.

I heard references to the same happening now in Ukraine.

Also, Ukraine just several weeks ago finally legalized the purchase of agricultural land by foreign entities. The pressure for this had been going on for about 20 years. A year or two ago, when Ukraine’s parliament shot down again the bill to allow sale of land to foreigners, the European court of human rights sent them a letter chastising them for limiting the human rights of landowners to freely sell to whoever they want.

So, selling your land and topsoil to the highest bidder is a human right. According to none other than ECHR.

Maybe ECHR next will object to limiting the human rights of those who want to sell other humans, I dont see why not if we follow the same logic.

This decision may strengthen the desire of East Ukrainians to seccede from West Ukraine . . . in order to avoid having all their survival farmland sold out from under them to predatory World Business.

The same logic would certainly apply to the buy and sale of “mineral rights” and “fracking rights”. And that might be another pressure driving East Ukraine to want to secede even more harderer.

And Banderastan can join the EU and sell all its farmland to the foreigner as much as it likes.

“corn and soy are mostly grown to produce ethanol and animal feed”

Slightly more units of energy are derived from ethanol than are used to produce it (diesel, coal and fertilizer made using natural gas). Slightly less CO2 is emitted.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethanol_fuel_energy_balance

Ethanol is another enormous debacle that nothing can be done about. Turning petroleum into plants and plants into fuel makes no sense at all.

Discussing the ethanol debacle as something which “something could” be done about would be a first step towards realistic efforts to do that something.

Realistically, it may have to start with the first brave Primary Season nomination-seeker deciding to boycott the Iowa Caucus-Primary and begin herm’s campaign in other states by saying ” if elected, I will seek the repeal of all ethanol subsidies and mandates, and the abolition of forced-ethanol in gasoline”. If heeshee could get more votes in non-Iowa than what heeshee lost in Iowa, that would be a first step towards turning the political system into a nail-studded baseball bat for beating ethanol’s skull in with.

The link for the definition of topsoil at the University of Sheffield is no longer functional.

The European Commission wants to ensure 75% of soils are healthy by 2030.

Caring for Soils is Caring for Life

That is a replacement for what was going to be a binding Directive – the Soils Directive. This would have set legal goals for all member states for soil preservation. The proposed Directive was essentially blocked by…. the UK. So there is hope now that it might be revived.

The first time I saw really shocking levels of soil erosion was in England when I was doing some walking and hiking trips when living there in the 1990’s. Even in beautiful prosperous Oxfordshire there were farms where all the hedgerows had been ripped out with cereal crops planted right up to the road edge – just walking along the edges you could see the run-off into local rivers and streams, not to mention multiple shards of Saxon pottery that had been ripped up by the ploughs. It made no sense economically or environmentally to do this – it was a brute force reminder of the power of the agriculture industry in the UK, which is amazing considering what a tiny portion of the economy it was and is.

Some soils in China, Japan, elsewhere have been farmed for several thousand years with no apparent loss of fertility so far as I have read or heard. Perhaps these soils have been “domesticated” over time.

Perhaps soil science should recognize the existence of “domestic soils” in regions of old or ancient horticulture-agriculture. Perhaps these soils should be studied AS domestic soils.

That Scientific American article which claims it takes some whole bunch of time to make an inch of topsoil may well have been overtaken by events and new knowledge on the part of certain growers who claim to have restored laid-bare subsoil to topsoil conditions and functionality at several inches per year. If these farmers have been debunked or disproved, lets hear about it.

One way to create a governance-field around the farmers of a country which would facilitate those farmers maintaining the soil they make a living from in the same condition which allows them to make the same living . . . would be for that country to reject the Free Trade System and re-Protectionise its own agriculture. With food imports harshly forbidden, the farmers of the country in question would be able to charge enough for their food to have the money to apply the time, management, inputs, etc. to their soil to keep it as soil. The non-farm people who would have to pay the higher price of food that non-growers would pay within the re-agri-protectionized country would be forced to understand and accept that the higher price of food will be the price they pay today to even conTINue to even HAVE food to eat tomorrow AT ALL.

Let those who disagree keep their countries in a state of Free Trade subjection leading to ongoing underpayment for farm production to their own farmers, which will default-force those farmers into underinvestment in maintaining their soil. Let those pro Free Trade publics continue driving their farmers into slow and steady bio-ecological bankruptcy through forced consumption of forcibly non-maintained soil eco-bio-capital. And let those pro Free Trade publics eat the mass soilicide, desertification , famine and death which Free Trade will bring them in the end.

As Joe Biden said in a different context against a different target population . . . ” I have no empathy”.

I have no empathy with people who want farmers to maintain their soil in existence but don’t want to pay their farmers enough to do that. Let such Agricultural Free Trade supporters and advocates starve to death and die in the long run, as they deserve. Let them eat tomorrow what they serve their farmers today.

I certainly don’t expect any help from the UN or other self-congratulatory Globaloidal power-trippers.

A group ( FAO) which would willingly and maliciously lie about the so-called “role” of livestock in global warming, when that group knows very well about the soil carbon increase that eco-scientific grazers and rotating farmer-grazers achieve and indeed will attempt to maliciously suppress knowledge of these practitioners and their methods by the sinister bait-and-switch gambit of deliberately mis-identifying feedlot corn-soy CAFOing with regenerative eco-modern grazing . . . . is an organization with precisely zero knowledge or integrity to contribute to anything at all whatsoever.

> Perhaps soil science should recognize the existence of “domestic soils” in regions of old or ancient horticulture-agriculture. Perhaps these soils should be studied AS domestic soils.

This is the French notion of terroir. There’s something in it!

> new knowledge on the part of certain growers who claim to have restored laid-bare subsoil to topsoil conditions and functionality at several inches per year. If these farmers have been debunked or disproved, lets hear about it.

We can’t debunk (or not debunk) something for which there’s no link!!

It is important to recognize different types of substrates for topsoil and the role they can play.

Iowa soils are geologically recent. They are from a variety of sources, including glacial till (ground up rock laid down by glaciers), loess (wind deposited silts from the sub-acrctic conditions along the edge fo the ice sheet during the last glaciation), and fluvial floodplain sediments from the Mississippi, etc. and generally date from within the 20 thousand years or so. These substrate soils are relatively unweathered parent materials with lots of minerals in them that can be unlocked by biological, chemical, and physical weathering during topsoil formation. These types of materials are available in the great agricultural parts of the world in North American, Eurasia (especially northern Europe, Russia, China), India, South America, and to a lesser extent, Africa.The process of topsoils formation by natural grasslands and forests builds a nutrient rich topsoil. Invetebrates burrowing in the materiasl helps build structure. Fungi help move water and nutrients from the soil to plants, and between plants. These areas can rebuild their topsoil fairly quickly, even if they have done a poor job with land husbandry, if they follow good practices.

Much more problematic are the parts of the world where the agricultural soils are “residual soils” formed from the immediate underlying bedrock. These tend to be very old soils, hundreds of thousands or millions of years old. Precipitation infiltrates down through these soils, leaching out minerals and nutrients and carrying them down deep into the underlying materials. Some amazonian tribes figured out terra preta a thousand years ago or so where they introduced charcoal, manure, urine, and other biological waste to create fertiel soils in these poor quality soils. The charcoal carbon lasts a very long time compared to most other carbons i nthe soil that volatilize fairly quickly due to microbial action (CO2). The knowledge of how to do this was lost when native cultures died out, mainly due to disruption by high death rates from disease after Europeans showed up. So many of these areas now use slash and burn agriculture where they cut down tropical rain forest and burn the wood. This creates a short-term pop of fertility, but when that runs out, they need to repeat the process, destroying more rain forest. A more nuanced approach with terra preta concepts would likely allow those areas to be farmed indefinitely instead of just a few years.

The most sustainable farmland are the new soils that are then farmed using some of the concepts focused on long-term sustainability, such as terra preta, or re-use of composted waste. Long-term traditions in places like China and European countries use this type of approach. So terroire is more than just the local land, it is also the farming practices. If you find an area with a geology and climate similar to another locale (e.g. Bordeaux, Burgundy, Alsace-Lorraine compare to Finger Lakes in upstate NY) then you can port those concepts to a new land and leverage centuries of experience. Canadian wheat/rye is very similar to the wheat/rye production in Ukraine and Russia, but became more mechanized due to the industrialization in North America. Specialty cheese in North America is now being made like in similar areas in Europe instead of the industrialized production of processed cheese common 30-50 years ago.

Present day scientists and others are studying terra preta to reverse-engineer the closest living eco-bio-facsimile they can. Here is a book about how to get functionally pretty close to it according to the best of our knowledge so far. It is from the Acres USA Bookstore, which is a NOmazon source.

https://www.acresusa.com/products/terra-preta

It is one of several German language books on soil and soil processes and management specifically which Acres USA has had translated and printed in English just lately.

Some of these man-grown soils could be called Domestic Soils if that becomes an accepted research and taxonomy concept. For ancient never-glaciated soils in the warm and hot leach-lands and abuse-lands, neo-soil neo-growers might have to bring in millions of tons of powder-fine crushed high multi-mineral rock to create the mineral nutri-basis for a humanly useful viable soil.

Many years ago I read in the Economist an article about how mineral-deprived soils in Piauy State Brazil were eco-upgraded with the mixing in of millions of tons of lime-type rock. Here is a book tangentially about some of that.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211912413000357

“neo-soil neo-growers have to bring in millions of tons of powder-fine crushed high multi-mineral rock to create the mineral nutri-basis for a humanly useful viable soil.”

Tonnage needed could be reduced considerably by focus on the one element that is most-depleted, and on which soil formation and much else depends: silicon.

Most of the principal materials for soil formation are silicon compounds:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedogenesis#Parent_material

(silicon plus a bit of Ca, Mg, K, Fe)

Silicon is the main reason that “rock dust” was successful as soil amendment, IMO. Grinding rock to dust greatly accelerates natural weathering, resulting in release of silicon much faster than waiting millennia for rain/wind/etc. to do the job.

The world’s soils are being depleted of silicon, by conventional agricultural practices, at the rate of 200+ MILLION TONS per year!

I understand that it would be too reductionistic to say that soil formation is all down to this one thing — available silicon. However, that IS the key limiting factor. Other stuff must be there, too, but soluble silicon is the main driver.

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2435.12704

https://journals.lww.com/soilsci/Fulltext/2016/09000/A_Review_of_Silicon_in_Soils_and_Plants_and_Its.1.aspx

When I have a time-chunk off of work, I will bring some links.

Being a grizzled veteran farmer, remembering my Grandfather muttering about those damn horses and growing up with the miracle of horsepower and now technology sweeping farm country, we still know little about the trillions of organisms just beneath our feet. But their time is coming, they are the basis of civilization afterall. Merlin Sheldrake details how we coevolved with fungi and is a great storyteller so there is much to discover. Being a food producer is an honor, but won’t get me into heaven by itself. Taking all that grows on my farm into consideration, including the weeds, is essential to establishing the long term relationship that generates the next crop. A recent farm survey in my inbox asked how many generations of farmers in my family, I said 100, all of us have farmers in our family tree. Beating swords into plowshares is the most damaging, inside out plea for peace ever. The bottom plow has done more to destroy our world than any tool or invention ever imagined or built. So there is lots to recover, to heal, thousands of years of hard scrabble farming to fill the granaries so the warlords could steal it. Seems more than crucial.

I have read that fungi and animals share certain common ancestry. They certainly share some digestive enzymes. In a very “strains-logic” sense, animals are fungi which are turned outside-in. Fungi bring the digestive system to the food. Animals bring the food to the digestive system.

Iowa’s black gold also gets bagged and sold to China. If you’ve become interested in soil science make sure you read Darwin’s amazing essay about earthworms and how they work. As with Freud and Marx, marvelous straightforward prose, fascinating, studded with the best kind of insight: that derived from common sense.

Twice in less than a year! This soil scientist is genuinely bowled over by so much thoughtful attention to something that just doesn’t have the glam factor of charismatic endangered biota or climate apocalypses. Thank you, Lambert.

There’s an important job for anthropologists / ethnographers here – finding examples of social practices which provide models of good governance of soil resources. All too often, when we argue about natural resource management, we’re given the false choice of either complete privatization or the tragedy of the commons. Yet, as Elinor Ostrom showed, there is a rich and complex heritage of successful stewardship of resources in many societies which rely on other means of implementing desirable norms. Although I’ve only dipped into her work, she tended to emphasize things like fisheries, and I don’t believe that soil stewardship ever got much attention.

Have you considered showing this and the last soil article to every soil scientist you know? To prime them for reading any future such articles which NaCap might post? And get them to offer considered and imformed comments on the subject in these relevant threads?

Check out David Montgomery’s book “Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations” or watch the lecture:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sQACN-XiqHU

Film: Kiss the Ground Tuesday, September 22, 2020,

Premieres on Netflix. This film explores the importance of

healthy soil to life on Earth. Find it at

https://kissthegroundmovie.com/

Here is a photo illustrating a proximate cause of some of these problems.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/antrover/28649538403/in/photostream/

Here’s another one.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/antrover/29074060310/in/photostream/

Unless these fields have been seeded with cover crop which will start growing to protect the soil, then they are as left-bare as they look. In which case, what is the pre-proximate cause of the particular example of proximate cause shown in these photos?