Yves here. I’m not sure I get this post. Seriously. It is clever to use the recovery from World War I and the Spanish Flu as a point of departure for discussing the real economy after Covid. But the world was vastly different then. Pre Great War globalization broke down. The major powers went back on the Gold Standard, although Peter Temin has argued, persuasively, that that was the worst thing they could have done and that it led to the Great Depression. And the world didn’t have to worry about resource scarcity and global warming back then either. And we aren’t yet done with Covid.

I also have trouble seeing the “Roaring Twenties” being depicted as a broad-based major economy phenomenon, even though he presents charts showing that for major European countries. England is not part of this picture and it was mired in borderline depression for most of the decade. Germany had crushing reparations, hyperinflation and then austerity leading to Creditanstalt. I will have to check with my economist buddy who did the definitive paper on Creditanstalt (including lots of archival work) and see if he agrees with this sunny view of Germany’s economic health.

My understanding of the US Roaring Twenties was it was a product of a technology boomlet plus borrowing (more home being electrified resulting in the introduction of mass consumer durable goods, with many purchases funded by loans, and as we know, stock market speculation with lots of leverage, such as trusts of trusts of trusts).

Despite what I regard as an odd slant, I’m running this post anyhow because the author make a lot of very interesting observations. So it serves as productive grist for thought. And maybe you’ll differ with me on the reservations about the framing.

By Alessio Terzi, Economist, European Commission. Originally published at VoxEU

Inspired by conspicuous historical parallels, some scholars and journalists have argued that GDP growth and productivity might boom in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic. This column reviews the evidence for and against the ‘Roaring Twenties’ hypothesis, concluding that some countries might well experience a forceful economic expansion. But policymakers should avoid complacency and make the most of the Recovery and Resilience Facility funds, combining them with wide-reaching structural reforms to improve economic prospects for the decade to come.

The ‘Roaring Twenties’ was a decade (approximately 1921–29) of growing prosperity in the Western world, alimented by deferred spending, a boom in construction, and the rapid expansion of consumer goods, such as automobiles and electric home appliances. These factors materialised on the back of WWI devastation and, crucially, the N1H1 ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic. As such, several pundits, journalists, commentators, and academics have been drawing parallels with that historical period, suggesting the post-Coronavirus recovery could be characterised by an economic boom, as illustrated in a recent cover story of The Economist. In this column, I review the evidence in favour and against a reiteration of the ‘Roaring Twenties’ in the 2020s, in order to draw policy lessons from the past.

There are indeed a host of parallels between current global conditions and those in the run up to the Roaring Twenties, albeit perhaps due to different underlying reasons. Analogies include the end of a pandemic (N1H1 then, Covid-19 now), the proliferation of new technologies (electricity then, AI/digitalisation now), a transport revolution (combustion engine then, electric vehicles now), political polarisation (rise of Communism and nationalism then, anti-establishment sentiments now), as well as emerging international rivalries, de-globalisation, and a soaring stock market.

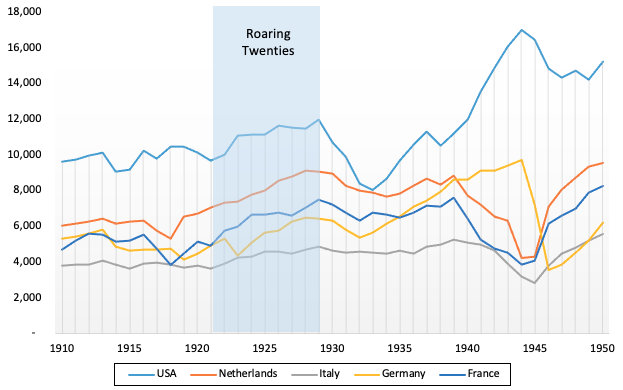

Figure 1 shows real GDP per capita across selected Western countries. Two things should be noted. First, irrespective of a common trend across Western countries, it is evident that the Roaring Twenties materialised to different extents in various nations. For all, the challenge was to transition out of a centralised wartime economy, and back to a peacetime economic structure. The process was hardly smooth. In some cases, it led to moments of economic crisis, such as in Italy in 1921, when two large industrial trusts, Ansaldo and Ilva, collapsed after having outgrown during the war. As a result, the trend of a Roaring Twenties is particularly visible in France and the Netherlands, after WWI, but less so in Italy.

In Germany, the decade was conspicuously characterised by hyperinflation, mainly due to money printing to finance the war, and then subsequent reparations. In the US, where the Roaring Twenties are most visible, GDP per capita went up from roughly $10,000 to almost $12,000 just before the 1929 stock market crash. Nonetheless, even there, the transition from a wartime to a peacetime economy was all but seamless. Lack of jobs for returning veterans led to strikes, social tension, and a rise in Communist sentiments – sentiments which were subsequently suppressed by the federal government.1 This is a period known as the ‘Red Scare’ (1919-1920). Eventually, the domestic rise of consumer credit fuelled consumerism, including for mass-produced cars like the Model T Ford. In parallel, the spread of electricity paved the way for a variety of home appliances, propelling the recovery.

Figure 1 Real GDP per capita for selected Western countries (2011 constant US dollars)

Source: Author based on Maddison historical data.

The second element to take away from Figure 1 is that the Roaring Twenties do not compare in magnitude to the post-WWII reconstruction boom in Europe.2 Perhaps what made them particularly ‘roaring’ – at least in terms of perception of progress at the time – was a comparison to a rather sluggish growth decade beforehand (something that holds true across countries). In 1921, US real income per capita was roughly at its 1906 level. This constitutes yet another parallel to the situation today, as Western countries in the aftermath of the Global Crisis have been characterised by so-called ‘secular stagnation’.

In what follows, I briefly list a set of arguments for and against the optimistic forecast of a high-growth decade for Europe following the end of the Covid-19 pandemic. In both cases, I will look first at the prospective for a cyclical short-term boost, and then the possibility that this feeds into a longer-term growth momentum.

The Roaring Enthusiasts

A variety of arguments have been used to push the view that we could experience a re-edition of the Roaring Twenties. These arguments often reach beyond standard macroeconomics, and include social psychology and management studies.

First, looking at the short term, some pin their hopes to the fact that the recovery from non-financial crises is generally faster than from financial crises such as the 2008/09 recession3 (Reinhart and Rogoff 2015). Indeed, early evidence from countries where the pandemic was brought under control, such as Australia,4 shows an extremely rapid recovery in growth and jobs. This is because non-financial crises generally produce less debt overhang, except in the private sector. While this could potentially curtail investment and weigh on long-term growth, the low interest rate environment makes debt burden more tolerable, not only for the public sector, but also for private companies. Finally, for Europe, Next Generation EU is expected to support investment and might end up being perfectly timed to kick in when the cyclical recovery will start to gather steam as the vaccine campaign reaches a critical mass.5

Second, and related to the point above, roaring optimists note that the European response has been swift and decisive. One year into the crisis, the economy has proved resilient and adaptable to operating in a pandemic environment, while manufacturing exports are supported by a strong nascent recovery in Asia, where Covid-19 is more under control. Although bankruptcies might increase once extraordinary support measures are lifted, these should be contained by a cyclical upswing once restrictions are removed (the so-called ‘mini-corona boom’). In this respect, the summer of 2020 – when economic activity effectively returned to pre-pandemic levels and a sharp GDP expansion ensued – lends scope for optimism. Evidently, the cyclical boom could be supported by excess savings and pent-up demand, on the back of the strong income support measures rolled out by EU governments. By some estimates, these excess savings could constitute a stimulus worth 3-6% of GDP across Europe (Kennedy 2021).

Further underpinning the prospects for a short-term boost, social scientists have pointed out to psychological factors dominating in the aftermath of a shock like a pandemic. In his most recent book, Apollo’s Arrow, Yale physician-turned-sociologist Nikolas Christakis argues that the aftermath of pandemics is typically characterised by a positive psychological uplifting, spurring social interactions, creativity, experimentation, risk-taking, and flourishing arts. Indeed, the 1920s was a time of liberation, in which women won the right to vote in several countries, and starting to wear more clothes of their choosing, smoke cigarettes, and drink in public – liberties that previously could not be enjoyed. In America, at the same time, Black poets, authors, and musicians found wider audiences, as part of what is commonly known as the ‘Harlem Renaissance’. Christakis argues we might observe similar patterns following Covid-19, as people rush to re-connect.6

On the back of all this, optimists see reasons to expect that, at the very least, Europe will rapidly return to its pre-crisis potential output, following a short-term cyclical boost once vaccines allow for a full re-opening of the economy.

From a more structural long-term standpoint, the conversation on the Roaring Twenties is linked to the long-standing debate between techno-enthusiasts – such as Erik Brynjolfsson at MIT – and techno-sceptics such as Robert Gordon at Northwestern University.7 Brynjolfsson has long argued that the digital revolution has been long brewing, and it is just a matter of time before we see its GDP and productivity boosting effects. This view is gaining policy attention, and was recently embraced also by Bank of England Chief Economist Andy Haldane.8

The Covid-19 pandemic, which severely reduced inter-personal contacts, forcing firms to digitalise, could have served as an accelerator of innovation and technological diffusion.9 Indeed, the World Economic Forum this year found that more than 80% of employers intend to accelerate plans to digitise their processes and provide more opportunities for remote work, while 50% plan to accelerate automation of production tasks. A global survey of executives by McKinsey & Co. revealed that many corporations were a ‘shocking’ seven years ahead of where they planned to be in terms of digitalisation. Finally, firms that made digital investments at the height of the crisis are likely to want to reap the benefits also once the pandemic is over. This could imply protracted hefty savings in terms of office space and business travel for companies, as well as cuts in commuting time for workers, leading to a structural boost in productivity statistics. Recently, even techno-pessimist Robert Gordon had to concur that Covid-induced digitalisation will most probably lead to a surge in productivity during the early 2020s.10

The Roaring Pessimists

Unsurprisingly, many representatives of the ‘dismal science’ have a variety of reasons to be more pessimistic about the future.

First, notwithstanding the strong crisis response at national and EU level, some damage in the economy will probably be unavoidable. Virus containment measures are likely to have affected individuals and workers through a variety of channels. In particular, there is ample evidence to suggest that young people who enter the job market during a recession face lower wages, which linger on for over a decade (Oreopoulos et al, 2012).11

A similar effect could materialise for workers who probably experienced some skill losses while idle during lockdowns. According to research by the World Bank, countries struck by pandemic outbreaks (before Covid-19) experienced a marked decline in labour productivity of 8% after three years relative to unaffected countries (World Bank, 2020). Along similar lines, IMF research based on 133 countries between 2001 and 2018, shows how pandemics tend to reduce output and increase inequality, stoking social unrest, further lowering output and worsening inequality (Sedik and Xu 2020).

In line with this pattern, the Roaring Twenties in the US were characterised by staggering inequality. This is best exemplified by F Scott Fitzgerald’s 1926 novel The Great Gatsby, slowly setting the scene for the Great Depression. In addition, it might very well be that the pandemic shock will lead to a structural increase in savings rates, as people become more cautious after having experienced unexpected hardship (Eichengreen 2021). If this were the case, ‘excess savings’ would be here to stay, diminishing the power of the pent-up demand optimistic argument, and further compounding the savings glut behind Larry Summer’s ‘secular stagnation’ hypothesis for advanced economies (see also Jordá et al 2020).

Second, the fact that a wave of bankruptcies has not materialised yet is simply due to the fact that state aid – together with debt moratoria and some degree of financial repression – have been rolled out forcefully, based on the presumption that the Covid-19 recession was fundamentally a liquidity crisis with transient impacts. Most, if not all, firms have been propped up. But once the pandemic dust settles, some sectors might have disappeared or declined permanently, with classic examples being structural transformations of retail (which moved to e-commerce) or business travel. Both sectors are unlikely to return to previous glories following the pandemic.12 Economic policies that were appropriate in the early phase of Covid-19 could impede this structural transformation, supporting irremediably stagnant sectors, generating ‘zombification’. Based on this risk and due to a lower resilience or capacity for swift transformation, in its latest WEO update the IMF expects the EU and euro area to return to pre-crisis levels of GDP much later than other advanced economies (such as the US and Japan).

Third, there has been a political consensus on using fiscal policy to support the economy so far. But the fiscal tool could be constrained going forward, depending on a variety of factors such as the future evolution of inflation and the ECB’s reaction to it, the retention of trust on financial markets, and the future evolution of EU fiscal rules. Fiscal policy could either become a drag on growth, or not be in the condition of being supportive should a new macroeconomic shock occur.

Fourth, Peruzzi and Terzi (2018) have shown that growth accelerations – meaning a structural and sustained increase in growth rates – remain rather elusive in advanced economies, and are typically associated with wide-reaching structural reforms. This argument speaks to Daniel Gros’ view that the effect of the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility will hinge mostly, if not fully, on whether it triggers wide-reaching structural reforms: something that remains far from obvious (Gros 2020).

Finally, taking a more global perspective, advanced economies have bought the vast majority of available vaccine supplies for 2021, in the hope of being able to save lives and re-open their economies swiftly.13 But the global nature of supply chains suggests that production and trade will remain disrupted so long as developing countries are affected by the pandemic. Çakmakli et al. (2021) have recently shown that up to half of the coronavirus-related economic damage in 2021 could still accrue to rich countries, even assuming fast and complete vaccination rates for their citizens. Beyond trade and production, the continued proliferation of the virus in other countries implies a persisting risk of vaccine-resistant variants developing and spreading globally (Brown et al. 2021). In other words, Covid-19 could have a protracted impact over years, which will not be resolved by a fast vaccination campaign in the next few months. This could hamper the prospects of a roaring decade.14

Conclusions

After reviewing both arguments in favour and against, a replication of the Roaring Twenties looks far from granted for Europe as a whole. But what cannot be excluded is that an economic boom might materialise for selected countries within the EU – perhaps on the back of a more successful rollout of the Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF) or an export-led model anchored to the resumption of global growth. We saw how exits from moments of crisis can pave the way for a differentiated recovery, even within a general supportive growth environment (as happened in the early 1920s). Further, large mega-trends like the shift to a new growth model based on the digital or green economy, and the challenges related to ageing, could further exacerbate the problem of uneven growth within the Union.

Different recovery paths, or a localised re-edition of the Roaring twenties, would have repercussions in terms of widening divergences in the EU on a variety of policy indicators. On the fiscal front, some countries might be better placed to rapidly re-absorb the high public debt levels incurred as a result of the Covid-19 crisis response. On the monetary policy front, diverging paths of economic success might once again create a ‘one size fits none’ problem for the ECB (Enderlein 2005). On the internal migration front, an uneven recovery could spark continued large involuntary migration of young people, as experienced following the euro area crisis, with vulnerable countries losing precious human capital. Evidently, all this would have rippling repercussions on political cohesion and consensual decision-making on the way forward in terms of EU policy integration. Within this context, national governments should avoid complacency inspired by parallels with the original Roaring Twenties. The ambition and quality of the public policy response to the crisis, including the degree to which Recovery and Resilience Fund is well spent, and coupled with wide-reaching structural reforms, is ultimately what will define economic prospects in the ‘twenties’ of the 21st century.

Author’s note: The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the institution to which he is affiliated.

See original post for references

I personally don’t see how there could be a roaring 20’s again. As a small business person I haven’t recovered from the Roaring Ought’s. Nation wide more than half of the stores in my field have gone out of business and still there has been no increase in individual store sales. FOR 17 YEARS!!!!! And of all debt that retailer’s took on in 2005-06 to expand, half of it is still in place!!

This is not just a consumer debt ridden society. It is a manufacturing and retailing business debt ridden society.

I agree, it does not seem appropriate to describe any business or individual’s current position as consisting of ‘excess savings’. Some countries have seen almost 10% GDP drop yoy, and private/commercial debt is at historic levels. Even private speculation is highly leveraged. ‘More saving required’ is my prognosis!

I would say that for the United States, that there is little comparison between the 1920s and the 2020s in terms of recovery. For one, the American economy in the 1920s was a mixture of small, medium and large companies that manufactured virtually everything that the country needed from masks to automobiles. A large segment still lived on small farms where they grew their own food and exported the rest to town and city markets. The disparity in wealth was not that great by comparison and a working man could earn enough to make a living for both himself and his family. Many owned their own homes and neither the war, the flu pandemic or the re-adjustment of the post war economy changed this much.

By comparison, large multinational corporations now dominate the American economy, particularly those on Wall Street. Manufacturing has been outsourced to other countries to the point that it is reliant on other countries to support their needs, even to such simple things as face masks. Not that many are farmers anymore and most farms are corporate run huge combines that cause extensive damage to the landscape. The disparity in wealth is worse than what it was a century ago and most institutions have been corrupted by the wealthy. A living wage is a joke and there are whole populations living on the streets to be joined by those whose rents have been temporarily frozen.

In short, the 1920s America had a solid base to build a recovery from but 2020s America does not have that base anymore. It got sold out.

@The RevKev, 10:53am

All true but… the US still has major hi tech capacity and industrial capacity in many other areas, and small businesses can emerge by the millions if enough money is around to pay for what they provide.

More importantly in the immediate sense is the massive injection of federal money into the economy: $1.9 trillion underway + $2 trillion soon, unconfirmed but it will be big. That’s about 10% of GDP already flowing into the economy and another 10% on the way, targeted to revive economic capacity, albeit over 8 years. That’s very big. In Europe the sums are much smaller as described by Thomas Fazi in yesterday’s NC.

It doesn’t mean the money will be spent to provide the security people need: a secure job, secure care in time of bad health, reliable help with young children and elderly parents. The roaring twenties didn’t have those things either. But it does mean lots of jobs for people and profits for businesses.

Much rather see the business activity/ production listed as PPP rather than GDP which is very misleading as they dump a number of financial transactions into the GDP report which has no bearing upon it.

And of course the hi-tech sector can only employ a small percentage of the population while the rest are hung out to dry, then you have the low wages paid to the bulk of the population with an ever-increasing destruction of the middle class I think you are way over optimistic for when you destroy your manufacturing base you are head in a downward direction which will take years to turn around.

The historian John Barry also had a recent article on this subject which I found insigthtful. He thinks it will be quite different this time. The younger demographics of those aflicted by the 1918 virus played a major impact on the social sentiment of the reopenings at the time. This along with the carnage of WWI felt by the same demographic created a sense of fatalism and survivor guilt that is not necessarily present this time around.

https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/03/18/roaring-2020s-coronavirus-flu-pandemic-john-m-barry-477016

“But what cannot be excluded is that an economic boom might materialise for selected countries within the EU – perhaps on the back of a more successful rollout of the Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF) or an export-led model anchored to the resumption of global growth…”

Everybody “exporting” and with no thought to sustainability and at the same time reductions in the standards of living. People are supposed to blindly cheerlead the dogmatic “export led, global growth mantra”.

It’s rote and lazy. It doesn’t talk about the specifics of what is growing and always assumes that any outcome is only positive (even if reality itself has to be denied).

I don’t see Covid, or the response to it, solving any of the problems that existed long before Covid and/or were exacerbated by Covid.

We don’t really know that Covid is “solved”.

As for all the talk of “productivity”…productive at EXACTLY what again?

I hope the authors will indulge me in one emotional post here. I’m staggeringly shocked at the audacity of the press (well, what’s left of it) to gas light their readers with ridiculous comparisons of the 1920’s to this current situation. We’re in an economic depression, masked only by insane amounts of government deficit spending literally never seen, except briefly around WW2.

As Yves rightly points out, the world was a lot different back then. Is this kind of pablum being doled out by the financial press just a pathetic attempt to cajole more and more suckers into the stock market/housing ponzis? Or something worse, a deliberate type of propaganda to get folks to accept the sorry state of the economy, where more and more folks are desperate and only surviving due to eviction moratoria, mortgage forbearance programs or juiced up UE bennies?

For crying out loud, we have entire industries like the airlines being subsidized by the state, yet the charade of them being “free market” entities continues, complete with stock buybacks and options granted to their management. This is nothing like the 1920’s, I don’t think there is any historical analog. The worst of both worlds.

We lie to ourselves over and over, it is so depressing.

Once we-the-lied-to recognize that some lie to others, and move on from that to ” they lie to us”; then we can go from depression to anger to rage and hate. If the rage and hate can be properly focused and channeled, it can lead us to attempt constructive action.

Ian Welsh wrote a blogpost about that called ” The Utility of Fear, Anger and Hate”.

https://www.ianwelsh.net/the-utility-of-fear-anger-and-hate/

The question is whether the quantity and quality of jobs will be there after the pandemic subsides?

The pandemic has accelerated industry trends on lowering their reliance on in-person gathered-in-bunches flimsy prone-to-illness human workers.

While the Industrial Revolution had had its way for more than 100 years in 1921, with pollution of the air, earth, and water still unaccounted as extremely negative externalities, the world was still “empty” by many measures. Imperialism was in full flower, with acknowledged awful consequences for the Global South, but human population was still under 2 billion, for example. Growth, without which capitalism cannot survive, was still a thing however it happened. The world is now full, period, and growth is no longer a thing other than among those whistling past the graveyard. Until “modern economics,” the bastard son of Political Economy, recognizes this, nothing will fundamentally change (for the better).

The late Mark Fisher and Fredric Jameson: It is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.

And on that happy note, I’ll be off on mental health leave for the rest of the day. Good Friday is a holiday where I work.

Cheers!

I have been listening to radio programmes called “Ideas” and have come away from them believing that after the covid there will have to be big, BIG changes and I’m not sure that any of them will be made. The biggest problem we have to face is how to deal with climate change. The change, of course, will really have to be in the behaviour of human beings which cannot, in my estimation, be solved solely through technology. The changes that will have to be made are mind boggling and I’m not sure that human beings can make those changes without being coerced by the things that will happen because of climate change. It is difficult to change on such a vast scale.

People who will not accept coercion from other people may well accept coercion from changing climate itself. Maybe.

I’m pretty sure you’re Canadian, JEHR–how many USites would actually listen to IDEAS? But to keep yourself from despair, take a break and listen to “Notions: thoughts not good enough to be Ideas” if you have any stuff archived from the Royal Canadian Air Farce (Ici Farce Canada). After reading the article above, everybody deserves a good laugh.

Very weak parallels that in my view are totally outweighed by the differences. Getting a car is fundamentally different than replacing a car with an EV. For all the talk of things like AI no one has really shown meaningful real applications. And, if anything AI will be used to reduce employment — or at a minimum keep the gains of productivity flowing to a select few not towards rising standards of living.

We also have to acknowledge that as bad as COVID has been the death rate in comparison to 1918-19 is low and certainly low as a percent of total population.

The US population grew 15% from 1910 to 1920 and 14% between 1930 and 1920. Typically this is thought of as a major economic driver. We are growing this fact and are aging as a society, as is China, Japan and much of Europe.

A friend with teenaged daughters was smug about the rise in male virginity and asexuality. Then I pointed out to him that the Spanish Flu of 1918 was immediately followed by the Flapper era.

I don’t think there are many economic parallels between the ’20s and now, but I’m expecting a big boom in parties. Not that it will save the hospitality industry: the parties I’m thinking of will be in homes, vacant lots and pastures, wherever poors can gather without paying bar prices.

Red scares… the political rise, and in many places, dominence, of the Klan… lynchings and the poll tax… the Open Shop… military occupations of regions with industrial strife…

Images of flappers and West Egg aside, the ’20’s were a brutal and reactionary period, setting the stage for much worse in many places.

I doubt the author’s predictions will pan out, and hope they don’t.

Seems irresponsible to focus on the Spanish Flu and not The Great War as the major economic event setting the stage for the Roaring Twenties. While its true that non financial crisis have quicker recovery times, I think its safe to say this is a unique event where no one knows what will happen. Anyone hoping for change should ruminate on Biden being the new face to deliver it.

I see some parallels, but the winds of secular stagnation were not as strong in the 20’s as they are now. There was the opportunity for a huge bubble in the 20’s at a scale never seen before. But we’ve just gotten through massive asset bubbles over the past three decades. Law of diminishing returns: we’re not going to get a bubble as powerful as that of the 90’s.

Also, the problem is that after the 20’s, we got the 30’s. Perhaps the underlying problem, papered over by the stock market bubble, was not so much related to agriculture, as is usually thought, but that of falling profit rates in manufacturing (Devine).

Marxist economists such as Michael Roberts and Robert Brenner (who has been posted here) theorize that our current malaise comes from falling profit rates, especially in industry, albeit with different explanations (Brenner, like Devine, believes it to be the result of a crisis of overproduction/under-utilization of capacity in manufacturing).

What if what we are really headed for, after what Roberts calls the sugar rush economy, is something like the 1930’s?

James Devine, “The causes of the 1929-33 great collapse: A Marxian

interpretation,” Research in Political Economy 14 (1994), 119-194 [76 pp.]

Neoclassical economics is the economics of the Roaring Twenties, the Wall Street Crash and the Great Depression.

What was the worst thing that ever happened to the US economy?

The Great Depression.

What caused it?

They were using neoclassical economics in the 1920s and had no idea what was really going on.

On the surface the roaring twenties seemed great, but it was being fuelled by the money creation of unproductive bank lending being used to fund the transfer of existing assets.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Money was being created, not wealth, and debt was building up in the US economy that would lead to 1929.

We weren’t really sure before, but this has been repeated everywhere with neoclassical economics being used for globalisation.

At 25.30 mins you can see the super imposed private debt-to-GDP ratios.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

No one realises the problems that are building up in the economy as they use an economics that doesn’t look at debt, neoclassical economics.

As you head towards the financial crisis, the economy booms due to the money creation of unproductive bank lending, as it did in the 1920s in the US.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

The financial crisis appears to come out of a clear blue sky when you use an economics that doesn’t consider debt, like neoclassical economics, as it did in 1929.

1929 – US

1991 – Japan

2008 – US, UK and Euro-zone

The PBoC saw the Chinese Minsky Moment coming and you can too by looking at the chart above.

The Chinese were lucky; it was very late in the day.

Everyone has made the same mistake; only the Chinese worked out what the problem was before the financial crisis.

One economics, one ideology.

Global groupthink.

Everyone makes the same mistakes.

The US was first and plunged into the Great Depression.

Japan could learn from the Great Depression to avoid this fate.

They avoided a Great Depression by saving the banks.

They killed growth for the next 30 years by leaving the debt in place.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

The West would learn little from Japan’s experience as our experts had put Japan’s problems down to demographics.

It’s not as bad as Japan as we didn’t let asset prices crash in the West, but it is this problem has made our economies so sluggish since 2008.

Western governments are always fighting the drag anchor of all that private debt in the economy, which tends to kill growth and inflation.

Japan has been like this since 1991.

There was one engine of global growth left, China.

They made the same mistake as everyone else.

The debt fuelled growth model has reached the end of the line and this is why the global economy was slowing down before the coronavirus.

No one has really got any idea what they are doing with neoclassical economics.

As bad today as it’s always been.

To get the full picture we need the timeline.

Economics the timeline.

Classical economics – observations and deductions from the world of small state, unregulated capitalism around them

Neoclassical economics – Where did that come from?

Keynesian economics – observations, deductions and fixes for the problems of neoclassical economics

Neoclassical economics – Why is that back again?

We thought small state, unregulated capitalism was something that it wasn’t as our ideas came from neoclassical economics, which has little connection with classical economics.

On bringing it back again, we had lost everything that had been learned in the 1930s and 1940s, by which time it had already demonstrated its flaws.

What did we lose from classical economics?

Housing costs and the cost of living should be low.

Employees get their money from wages and employers have to pay these costs in wages reducing profit.

What did we lose from the 1930s?

They had worked out what went wrong in the 1920s.

Banks can inflate asset prices with the money they create from bank loans.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

When you think you are creating wealth by inflating asset prices (the markets are going up, yippee!) banks can use bank credit to fund the transfer of existing assets and push up prices.

They needed a better measure to see what was going on in the economy and invented GDP.

The real wealth creation in the economy is measured by GDP.

The transfer of existing assets, like stocks and real estate, doesn’t create real wealth and therefore does not add to GDP.

Real wealth creation involves real work, producing new goods and services in the economy.

China has the advantage because they are creating real wealth.

The Americans are just messing about transferring existing financial assets around.

This creates money, not wealth.

The Chinese did make the same mistake, but in a different way.

They built empty cities with bank credit, this didn’t add to GDP.

Everyone else just transferred existing financial assets around so they had nothing tangible to show for it.

I think its quite likely that with a new paradigm favouring looser fiscal policies in many countries that there will be a substantial period of growth in the mid time frame, but I’m finding it hard to see any other drivers of real growth. Unless I’m missing something I don’t see any fundamental changes in technology occurring that could drive a wave of productivity increases. Maybe a green industrial revolution will, although I suspect that will be more the result of direct government funding than a genuine productivity increase.

A potential problem is that things like AI, if they fulfil their promise, could actually result in productivity improvements that don’t make lives better or add to real growth – they have the potential to wipe out a lot of mid range jobs while just replacing them with baristas. In other words, the gains from productivity will go to the very wealthy, and won’t trickle down. There are precedents for this – the early industrial revolution caused havoc among the peasant and craftsman levels of society. Even the switch to farming in the mesolithic neolithic seems to have resulted in more ill health among the population, even while that population increased substantially and gained in ‘physical’ goods.

It’s possible we have been liberated, financially. We might finally be too complacent to get off the couch and go down and withdraw all our money from the bank. As far as I can tell, with the exception of a few throwbacks, we have totally different ideas about debt, deficits and money itself now. Nobody is suggesting that we gin up the economy, make it run in high gear, become mercantilist traders and pay down the national debt and have a dollar worth more than god. That is too funny to even think about. Everybody knows the environment and all the natural wealth has been gobbled up to create human wealth. Calvin Coolidge was responsible for stimulating the economy in the 20s in order to pay down WW1 debt. Much like Clinton throwing us into a recession spiral in the 90s by “balancing the budget,” or Obama’s stealth austerity. We have always pulled ourselves out of these recessions by using the MIC and engaging in wars for freedom and democracy. Which has become embarrassing to even think about. And, like quicksand, we still always wind up with some updated version of imperialism. “But we can change, if we have to, I guess.” We might have Richard Nixon and John Connally to thank for proving the value and usefulness of sovereign money even though we are only just coming to terms with this novel idea now. But, just in time to repair all the damage we have caused. Which will be one of the most valuable things the human race has ever done. Worth more trillions than we can even print. Who needs the self defeating absurdity of another “Roaring 20s” or another war? Massive growth in reclamation, reparation, and restoration is a much better choice. So, as usual, it’s a question of how, not what, we spend.

Economically there were no “roaring 20s ” in the US; the slope of GNP growth was consistent from the end of the 1890s panic to 1929. There was a wartime pop up and then swoop down; the long-term slope remained the same. But there was a 1920s boom in speculation.

Apocalyptic times (the Black Death, WW I, the “Spanish” flu; the mostly forgotten sleeping sickness epidemic in 1919-20) often bring out the “let’s party like there’s no tomorrow” spirit.

Immigration to the U.S. essentially ended in 1913 and in 1918 European industry was seriously damaged. Both of these tended to drive up wages for the U.S. working class at exactly the same time the internal combustion engine and radio matured. They gave unprecedented freedom to the young and the working class. Finally, the last act of the anti-immigration campaign was prohibition, a very popular “solution” to a social problem among the immigrants. It failed and led to a breakdown in the public’s usual passive support of “the law”. The best short read on the U.S. in the 20s is “Only Yesterday” by Allen.

And in 1914 there were serious strategic material shortages, which led to the race to carve-up Africa and create spheres of interest and control elsewhere. The drift to war that ended in 1914 with the killing of the Archduke was largely about access to resources. Germany and Austria became the besieged states without access to colonial resources and equally important, soldiers, so they lost. One solution was proposed by Keynes; it wasn’t seriously tried at the time. Another solution was proposed by a very bright autodidact on the loosing side names Hitler; it was tried from 1939-45 and came close to succeeding. . Mr. Hitler would be forgotten today if it hadn’t been for Creditenstahl, the crash and a burst appendix which killed the only universally respected and trusted German socialist leader in 1926. Talk about might-have-beens…

Resources are a limiting factor for any industrial period. The technology of 1900-30 could barely support two billion people. Thanks to Norman Borlaug, et al we got a second chance on food production in the 1970s, so maybe we can support eight billion… and maybe not.

If Yves knows of a good, readable history of Creditenstahl I’d love to read it.

See here:

https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/63870/madeingermanyger00ferg.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

@Dave in Austin

“Economically there were no “roaring 20s ” in the US”. A contrary anecdote: my father who was born in 1901 and lived through the “roaring 20s” often spoke to me of them fondly as a time of economic prosperity. He lived in Canada but the two economies were very much entwined.

I have no disagreement with the rest of what you wrote.

Excuse me? Which of the two panics in the 1890s are you counting, 1893 or 1896 — or are they one extended event by your definition? And how do we skip over the two panics, one depression, and six recessions between them and 1929?

The us was in the 1920’s the world’s big exporter, and logically took the biggest economic hit in the 30’s as ROW went into recession and could no longer afford imports. Huge loss of us jobs resulted in us depression. Neither fed or treasury would be able to meaningfully act until Roosevelt took us off the gold standard (1933?). helpfully, Britain provided the example, they had recently abandoned the standard (1931?).

The present situation could hardly be more different. China and Germany are vulnerable, but so far importers continue importing as central banks stave off recession by taking the role of lender of last result with great gusto. Preventing recession in the us has IMO prevented a more serious recession among the exporters.

Is 2T infra spending sufficient to hire those that lost their jobs (restaurant, leisure workers)? Maybe mismatched skill set… shortage of trades people in my region…